Martin Luther King, Jr. had a dream of racial equality and freedom for all people. But he also had a dream of a better nation, a better world, where social justice and caring for the poorest among us were more important than military spending and political games.

On the surface it seems there is more racial equality than there was when he marched on Selma, Alabama. But there is still discrimination and bigotry, it's just more subtle and covert.

The other dream he held, well, I think he would be seriously discouraged to see the America we now have, where government budget cuts impact the poor, the homeless, the hungry, and the mentally ill first, and military spending is a sacred cow that can never be touched - where partisanship on both sides is more important than solving our problems.

In memory of Dr. King, here are a few of his quotes about the nation he hoped we might become.

- A nation or civilization that continues to produce soft-minded men

purchases its own spiritual death on the installment plan.

- A nation that continues

year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of

social uplift is approaching spiritual doom.

- A riot is the language of

the unheard.

- An individual has not

started living until he can rise above the narrow confines of his

individualistic concerns to the broader concerns of all humanity.

- Darkness cannot drive out

darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do

that.

- Every man must decide

whether he will walk in the light of creative altruism or in the darkness of

destructive selfishness.

- Everything that we see is a

shadow cast by that which we do not see.

- Have we not come to such an impasse in the modern world that we must

love our enemies - or else? The chain reaction of evil - hate begetting hate,

wars producing more wars - must be broken, or else we shall be plunged into the

dark abyss of annihilation.

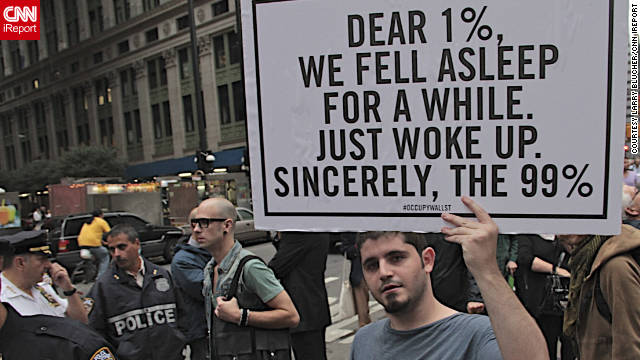

- He who passively accepts

evil is as much involved in it as he who helps to perpetrate it. He who accepts

evil without protesting against it is really cooperating with it.

- History will have to record

that the greatest tragedy of this period of social transition was not the

strident clamor of the bad people, but the appalling silence of the good

people.

- Human progress is neither

automatic nor inevitable... Every step toward the goal of justice requires

sacrifice, suffering, and struggle; the tireless exertions and passionate

concern of dedicated individuals.

- Life's most persistent and urgent question is, 'What are you doing

for others?'

- Love is the only force

capable of transforming an enemy into friend.

- Man must evolve for all

human conflict a method which rejects revenge, aggression and retaliation. The

foundation of such a method is love.