Edelman in 2009

I was sad to read this - and I feel fortunate to have seen Dr. Edelman speak in a keynote address at the 2013 Evolution of Psychotherapy Conference in December. I have been very influenced by his theory of consciousness and his tendency toward an interdisciplinary approach to science.

Edelman was awarded the 1972 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (shared with Rodney Robert Porter) for work on the immune system - in which he mapped a key immunological structure — the antibody — that had previously been uncharted.

He later showed that the way the components of the immune system evolve over the life of the individual is analogous to the way the components of the brain evolve in a lifetime. He is also credited with discovery of the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM), which allows nerve cells to bind to one another (a kind of "cellular glue") and form the circuits of the nervous system.

His many books for a popular audience include The Remembered Present: A Biological Theory of Consciousness (1990), Bright Air, Brilliant Fire: On The Matter Of The Mind (1992), A Universe Of Consciousness: How Matter Becomes Imagination (2001, with Giulio Tononi), Wider Than the Sky: The Phenomenal Gift of Consciousness (2004) and Second Nature: Brain Science and Human Knowledge (2007). Dr. Edelman was the founder and director of The Neurosciences Institute and was on the scientific board of the World Knowledge Dialogue project.

Here is an obituary from The Washington Post:

Gerald M. Edelman, Nobel Prize-winning scientist, dies at 84

By Emily Langer, Published: May 22

Gerald M. Edelman, a Nobel Prize-winning scientist who was credited with unlocking mysteries of the immune and nervous systems and later ventured into ambitious studies of the human mind, died May 17 at his home in La Jolla, Calif. He was 84.

His son David Edelman confirmed the death and said his father had Parkinson’s disease.

(AP) - Dr. Edelman, shown here in 1972 at his laboratory at Rockefeller University, shared the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for his discoveries related to the chemical structure of antibodies.

Once an aspiring violinist, Dr. Edelman ultimately pursued a scientific career that spanned decades and defied categorization. His Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine, which he shared in 1972 with the British scientist Rodney R. Porter, recognized his discoveries related to the chemical structure of antibodies.

Antibodies are agents used by the immune system to attack bacteria, viruses and other intruders in the body. But Dr. Edelman did not consider himself an immunologist.

He later embraced neuroscience, and particularly the study of how the nervous system is constructed beginning in the embryonic stage.

He was credited with leading the seminal discovery of a sort of cellular glue, called the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM), which allows nerve cells to bind to one another and form the circuits of the nervous system. But he concluded that such biochemical discoveries, however significant, could not fully elucidate the workings of the brain.

Dr. Edelman was associated for many years with Rockefeller University in New York City, where he directed the Neurosciences Institute that today is located in La Jolla. He delved into questions on the vanguard of neuroscience, including the study of human consciousness, and developed a theory of brain function called neural Darwinism.

Some scientists regarded his later work as unverifiable or muddled. The late Francis H.C. Crick, co-discoverer of the double-helix structure of DNA, was said to have dismissed neural Darwinism as “neural Edelmanism.” Others admired Dr. Edelman for daring to broach one of the most vexing questions in science.

He “straddled . . . frontier fields in biology and biomedical science in the last century,” said Anthony-Samuel LaMantia, the director of the Washington-based George Washington Institute for Neuroscience, describing Dr. Edelman as “one of the major intellects in science.”

In his earliest noted work, Dr. Edelman essentially mapped a key immunological structure — the antibody — that had previously been uncharted. “Never before has a molecule approaching this complexity been deciphered,” the New York Times reported in 1969, when the extent of Dr. Edelman’s findings were announced.

Dr. Edelman also was credited with recasting scientific understanding of how antibodies operate. When an antigen, or foreign agent, enters the body, a healthy immune system produces antibodies to attack it. Before Dr. Edelman’s studies, many scientists accepted the notion that antibodies altered their characteristics in order to match the features of the antigen.

Dr. Edelman’s research, which relied on the laboratory examination of quickly reproducing cancer cells, revealed another system in place, said Patricia Maness, a former colleague of Dr. Edelman’s who today is a professor of biochemistry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Research led by Dr. Edelman showed that the body has a “repertoire” of antibody-producing cells, she said. When a foreign agent enters the body, the immune system recognizes the intruder and begins producing in quantity the antibody best equipped for the battle. It was a process of selection, Maness explained, not adaptation or instruction, as had previously been thought.

“There is an enormous storehouse of lymphoid cells which are locks but don’t know they are locks — like a character in a Pirandello play — until the key finds them,” Dr. Edelman once told an interviewer.

The announcement of the Nobel Prize credited Dr. Edelman and his co-recipient with having made “a break-through that immediately incited a fervent research activity the whole world over, in all fields of immunological science, yielding results of practical value for clinical diagnostics and therapy.”

Dr. Edelman led a similarly groundbreaking discovery in neuroscience. Before his work, scientists did not know with certainty how nerve cells combine to form the nervous system. Through his work, Dr. Edelman showed that nerve cells do not affix themselves to each another like Velcro, LaMantia explained.

Rather, two nerve cells connect when surface molecules — NCAMs — recognize each other, setting off a chemical reaction that links the cells and in time forms a system.

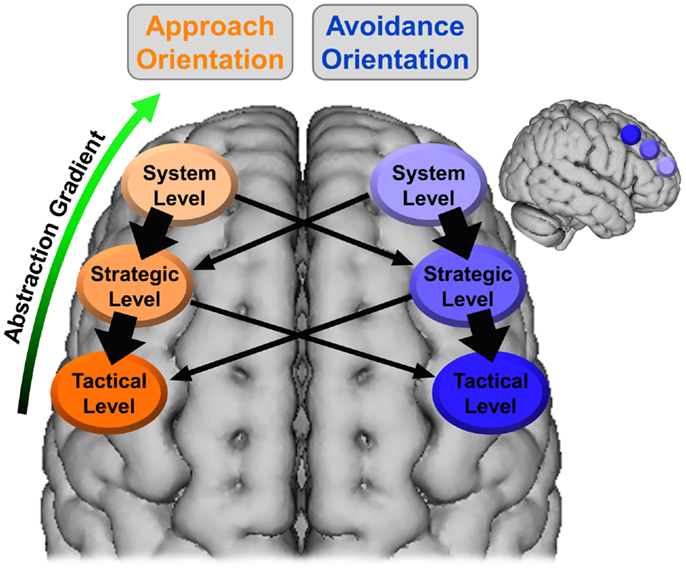

Later in his career, Dr. Edelman went beyond chemistry to develop his theory of brain function. He postulated that the brain is not like a computer, hard-wired for certain capacities, but rather is sculpted over time through experiences that strengthen neuronal connections.

Some scientists who seemingly should have been able to understand the theory said simply that they did not. Others regarded Dr. Edelman as a pioneer. Oliver Sacks, the noted neurologist and writer, credited him with having offered “the first truly global theory of mind and consciousness, the first biological theory of individuality and autonomy.”

Gerald Maurice Edelman was born July 1, 1929, in Queens. His father was a general physician in the era when doctors made house calls.

After pursuing classical music training, Dr. Edelman shifted to the sciences, receiving a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1950 from Ursinus College in Collegeville, Pa., and a medical degree in 1954 from the University of Pennsylvania.

Following service as an Army doctor in France — it was his F. Scott Fitz-Edelman period, he told the New Yorker magazine — he received a PhD in chemistry in 1960.

In addition to his other appointments, Dr. Edelman was a professor at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla. He wrote prolifically for academic audiences and general readers. His volumes included “Neural Darwinism: The Theory of Neuronal Group Selection” (1987), “Bright Air, Brilliant Fire: On the Matter of the Mind”(1992) and “Wider Than the Sky: The Phenomenal Gift of Consciousness” (2004).

Survivors include his wife of 64 years, Maxine Morrison Edelman of La Jolla; and three children, Eric Edelman of New York City, David Edelman of Bennington, Vt., and Judith Edelman of La Jolla.

“I know that people have tried to reduce human beings to machines,” Dr. Edelman once told the Times, seeking to explain the limits he saw in some prevailing notions of science, “but then they are not left with much that we consider truly human, are they?’’