However, the fact that mainstream science is catching on the how smart crows are bodes well for their future in intelligence research. Now if we could just ban hunting and killing them.

This article is from Misc.ience - there is a second one from Wired (below):

Crows join humans in the ability to infer hidden causal agents

New Caledonian crows – smarter every time we look at them.

A fascinating new piece of research was published a couple of days ago in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (or PNAS for short).

It shows that New Caledonian crows are capable of a cognitive feat previously only thought to be doable by human beings – the ability to reason about a hidden causal agent (in this case someone behind a sheet). Inference, in other words.

As the (open access/free) paper explains in its opening sentences:

The ability to make inferences about hidden causal mechanisms underpins scientific and religious thought. It also facilitates the understanding of social interactions and the production of sophisticated tool-using behaviors. However, although animals can reason about the outcomes of accidental interventions, only humans have been shown to make inferences about hidden causal mechanisms."Alex Taylor of the University of Auckland’s School of Psychology (hooray NZ!) and colleagues have shown, however, that we’re NOT the only creatures capable of doing it.

They took eight Caledonian crows – very clever birds, admittedly, who’ve previously been shown to be capable of making and using tools – and showed two series of events. Before the events, the crows had been given some experience with extracting food from a box using a tool.

Both events involved a sheet, and a stick which moved.

The first set of events: the Hidden Causal Agent (HCA)

In the first set of events, the crows were able to watch as a person (of the human sort) walked behind a blue sheet that was hanging up near to a box containing food. The box had been set up so that the crows had to turn their heads away from watching the sheet in order to get their food out.

Once the human had walked behind the sheet, the crows saw the stick poking out from behind it move, making motions towards the food box, and then they saw the human leave again. ’Meh’, one could imagine the crows thinking, ‘makes total sense. Fudz om nom nom.’

And that’s what they did – they came down to the food box, picked up a tool and extracted their food, giving nary a glance towards the sheet.

Ah, yes. There was also a second person who came into the room with the first, stood in the corner 1.5m from the sheet with closed eyes and hands held crossed in front of their body. This second person did nothing, and then left with the first person.

The second event: the Unknown Causal Agent (UCA)

In the second set of events, they saw the stick move in the same way without someone walking behind, or walking away from, the sheet. A ghost stick!*

As in the first event, there was also a second person who did nothing at all and then left.

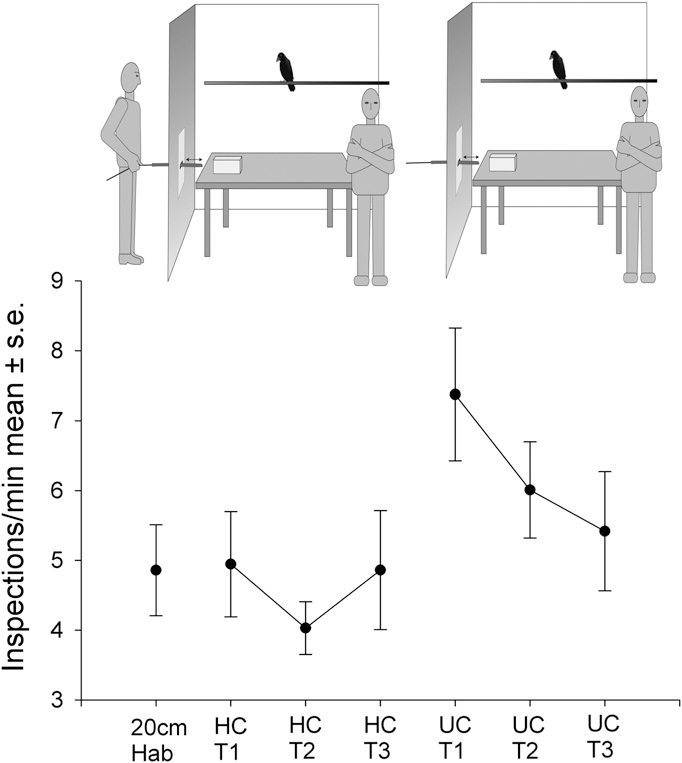

Inspection rate across conditions. Final habituation trial before testing is indicated by 20cm hab. (Upper Left ) Diagram of the HCA condition. (Upper Right) Diagram of the UCA condition. In the HCA condition, one human walked into the hide and one stood in the corner of the room. A wooden stick was then probed from the hide. The agent then exited the hide. Both humans then left the room. In the UCA condition, one human entered the cage and stood in the corner. The tool was then probed through the hole. The human then left. (Taylor, A.H. et al, 2012)

And so?

The experiment had been designed so that this stick stimulus would be a new experience for the crows, and so probably something they’d intrinsically distrust (or not like, at the very least)**.

Read the whole article. And here is another one from Wired.

Whodunit? Crows Ask That Question, Too

- September 18, 2012

A New Caledonian crow uses a twig tool. Image: Mick Sibley

By Virginia Morell, ScienceNOW

Imagine hearing a distant roll of thunder and wondering what caused it. Even asking that question is a sign that you, like all humans, can perform a type of sophisticated thinking known as “causal reasoning”—inferring that mechanisms you can’t see may be responsible for something. But humans aren’t alone in this ability: New Caledonian crows can also reason about hidden mechanisms, or “causal agents,” a team of scientists report Sept. 17 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. It’s the first time that this cognitive ability has been experimentally demonstrated in a species other than humans, and the method may help scientists understand how this type of reasoning evolved, the researchers say.

Causal reasoning is “one of the most powerful human abilities,” says Alison Gopnik, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved in the study. “It’s at the root of our understanding of the world and one another.” Indeed, it is the key mental ability for many things humans do, including inventing, making, and using tools. We develop this ability early in life: A 2007 study in Developmental Psychology reported that human infants as young as 7 months old understand that when a beanbag is tossed from behind a screen, something or someone must have thrown it. The infants infer that a “causal agent” must be involved in the motion of the flying beanbag.

But why should this ability be limited to humans? “It seems like it would make good sense for crows and many other animals to be able to distinguish between the wind rustling tree limbs and an unseen animal crashing through the canopy,” says Alex Taylor, an evolutionary psychologist at the University of Auckland in New Zealand and the lead author of the new study. Because New Caledonian crows are also inventive and skillful tool-users, Taylor and his colleagues thought the birds might have causal reasoning skills similar to those of humans.

Working on Mare Island in New Caledonia, the scientists captured eight wild crows (five adults and three juveniles) and housed them inside a large outdoor aviary. Over the next few days, the birds used a slender stick to extract food from a small box placed on a table in the aviary. Then the plot thickened: The scientists placed the food box close to a blue tarp large enough for a person to hide behind. The researchers also set up a large stick that could be poked through the tarp and waved around by a human outside the aviary pulling on a string; the moving stick posed a danger to the birds if they tried to extract the food.

The crows in the aviary then observed two different situations. In one, the “hidden causal agent” scenario, the crows saw a human enter the blind. Then, a few moments later, the stick poked through the tarp and moved back and forth 15 times. The human then exited the blind. In the “unknown causal agent” scenario, the crows saw only the stick as it emerged from the tarp and moved back and forth 15 times.

In both situations, a human also stood next to the table in the aviary, so the crows never tried to get the food. And in both cases, when the visible human left, the crows began to remove their food from the box. Yet the crows’ behavior differed depending on whether they had seen a human come and go from the blind. If the birds had seen a human stepping out of the blind, they seldom gave the stick so much as a glance as they dug out their food. But the crows that saw the stick move but no one emerge from the blind were nervous: They often stopped probing for food and studied the blue tarp and stick—apparently suspecting that someone or something unknown had caused the stick to move and that it might move again. Some even flew away from the setup.

Together, the tests show that the crows are “capable of causal reasoning,” Taylor says. “We expected the crows to initially be scared of the moving stick. Instead, they only became scared when they could not attribute the movement to a hidden human—which suggests the crows were reasoning that the stick’s movement was caused by that human.” The crows, he says, apparently don’t expect an inanimate object to move on its own, just as infants don’t expect beanbags to be tossed through the air by a toy block.

“It’s an extremely clever study,” says John Marzluff, a wildlife biologist at the University of Washington, Seattle. “Using a controlled experiment, they’ve validated what many crow hunters know—that crows keep track of hunters in blinds. Even if the crows [in this study] never see a person push the stick, they connect the dots between the location of a person and the actions they associate with people.”

The study “makes important new advances in our understanding of the extent to which nonhuman animals may be capable of causal reasoning and offers the potential to open this whole area up to scientific inquiry in animals,” adds Nicola Clayton, an experimental psychologist at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom. Because it suggests that causal reasoning evolved in parallel in humans and crows, the work may even “help solve the fascinating question of just how and why our human intelligence evolved,” Gopnik says.

This story provided by ScienceNOW, the daily online news service of the journal Science.