In recent post featuring

Trevor Malkinson's - Rhizomatic for the People: Notes on Networks and Decentralization, I suggested that the rhizomatic philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari, in many ways, overturns some of the basic tenets of integral theory - a model that is completely hierarchical, chronological, and highly organized. Rhizomes reject hierarchies and they resist chronology and organization. Rhizomes are decentralized, organized by connections and associations and not by systems, and they seek a unification that is inherently multiple.

This is not to say, however, that hierarchies must be tossed to the dustbin of history. In fact, nature is filled with hierarchies, as are human bodies and human relationships. Most obviously, we have bodies composed of organs that are composed of cells that are compose of molecules that are composed of protons and neutrons, that are composed of quarks, and which may be composed of one-dimensional strings (if string theory turns out to be true).

Talk about a hierarchy! Ken Wilber's AQAL version of integral theory assigns these hierarchies to a quadrant model of interior vs exterior and individual vs. collective. But his model seriously neglects that rhizomatic reality of many systems, both human and otherwise.

Anyway, I often place a lot of emphasis on relational, intersubjective and rhizomatic models here, but this is largely to fill the gap in integral theory that has neglected these models. But as I said, hierarchies are also very natural and important, as William Grassie shows in this article from

MetaNexus.

The Great Matrix of Being

February 26, 2013

By William Grassie

Understanding Natural Hierarchies

Our European ancestors once understood the universe to be a Great Chain of Being. All the entities of the world -- animal, vegetable, mineral -- were hierarchically organized. At the bottom were metals, precious metals, and precious stones. Then came plants and trees, followed by wild animals and domesticated animals. Humans were also hierarchically ordered from children to women to men and further into the different ranks of commoners, nobility, princes, and kings. The Great Chain of Being continued up into the celestial realm -- moon, stars, angels, and archangels -- to the very top where God presides over the entire creation. This scala naturae provided humans with a natural order, which they also understood to be a natural human order that structured their societies.

Retorica Christiana, written by Didacus Valdes in 1579, Source: Wiki Media

Science, or so the story goes, disrupted this view of the universe and ourselves. Copernicus, Galileo, and Kepler broke the crystalline spheres of Ptolemy and demoted Earth from the center of the universe to an insignificant periphery. Darwin understood plants and animals, including the human animal, to be evolving from common ancestors all the way back into the proverbial primordial slime. Freud showed that rational man was really an unconscious mess and hardly aware of, let alone in control of, his own thoughts and passions.

The Great Chain of Being was rendered a tangled web of happenstance in an enormous universe devoid of transcendence and meaning. God was rendered an unnecessary or incompetent creator. The new existentialists and Stoics argued that the universe was indifferent, that humans were insignificant, that our consciousness was epiphenomenal, and that our evolution merely accidental.

This turns out to be quite a distortion of the actual science and history. For while there is no Great Chain of Being, as the medievals understood it, there is most definitely a Great Matrix to which all beings belong.

Everything that exists in the universe, every process that science has discovered, every power of nature that humanity has harnessed, all that constitutes our human bodies and brains, our histories and cultures--all this and more--can be located within a number of natural hierarchies. These hierarchies define the Great Matrix of Being, and are measured in:

1) chronology

2) size

3) energy flows

4) electromagnetic radiation

5) thresholds of emergent complexity

Let's take a look at each in turn:

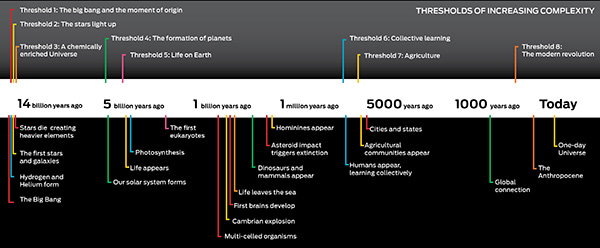

1. Chronology: The universe has a scale of time measured in billions of years down to the nanosecond vibrations of cesium in atomic clocks. Our best calculations suggest that the universe is 13.7 billion years old, that the Earth is 4.6 billion years old, that humans are 200,000 years old, and that the drama of human civilization began some 12,000 years ago. Today, we call this chronological understanding of the universe and ourselves "Big History." There are currently a number of initiatives seeking to promote this curriculum in education. Chronology, however, is only one dimension of the Matrix.

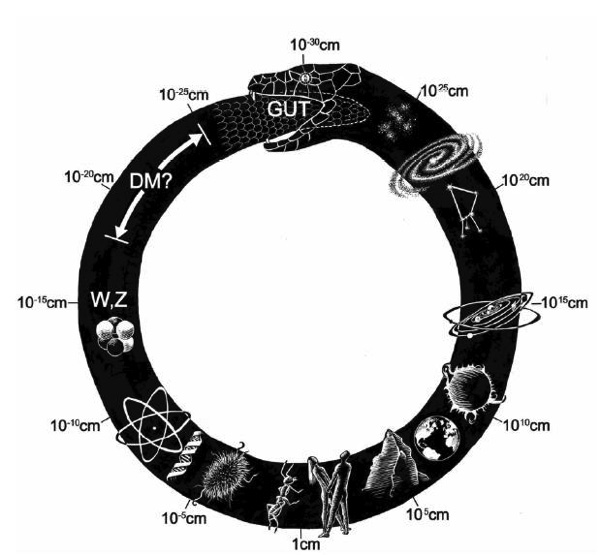

2. Size: The universe also has a size scale. The smallest unit is the Planck scale -- 1.616252 x 10-35 m. The concepts of size and distance break down at this scale as quantum indeterminacy becomes absolute. The most distant thing that we observationally know of in the universe is the background radiation from the big bang, which is 13.7 billion light-years away from Earth (13.7 x 109) x (3 x 109 meters/second). When we talk about the very fast, the very dense, and the very hot, these concepts of space and time become elastic, but in between these extremes, size matters. And curiously, the human scale--measured in centimeters and meters--exists about halfway between the very small and the very large and is the only scale where certain types of complexity could exist.

We tend to focus on how puny we are in the scale of hundreds of billions of galaxies, but we should also remember how enormous we are when compared with the atomic and subatomic levels. Space-time is a continuum in relativity theory, but for human purposes we normally treat them separately. Chronology and size are the x and y axes that establish the Matrix in two dimensions.

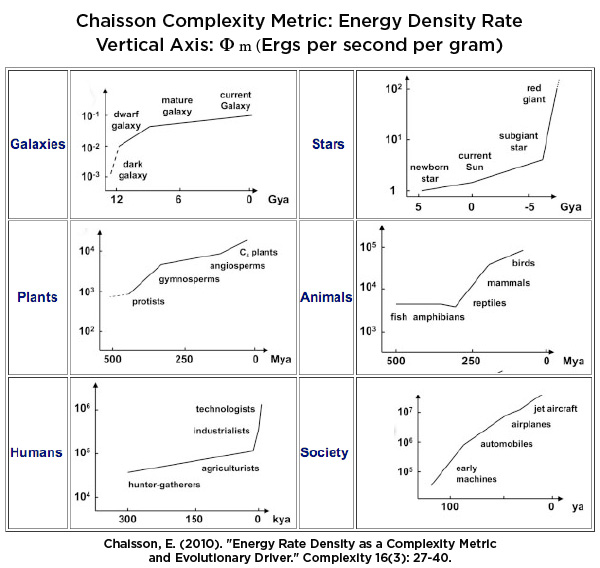

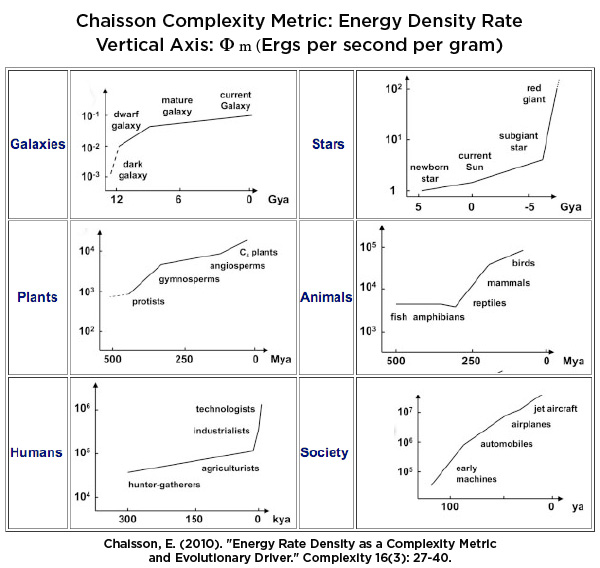

3. Energy: The intensity of energy flows is another axis in the Matrix. There is no uniform measurement of energy because energy comes in so many different flavors, including heat, electrical, chemical, nuclear, and kinetic. Physicists calculate the energy of the universe at the moment of the big bang as 1019 GeV (billion electron volts). At the opposite end is absolute zero or minus 273.15 degrees Celsius (minus 459.67 degrees Fahrenheit). At both extremes, matter exhibits strange behaviors.

All complex phenomena in the universe can be characterized by energy gradients, which we can measure in ergs per second per gram. It is counter-intuitive, but when normalized for mass, a photosynthesizing plant has about 2,000 times the energy density flow of the sun. A mammalian body has about 20,000 times the energy density flow of the sun. The human brain, consisting of about 2 percent of our body weight but consuming about 20 percent of our food energy, has an energy density flow about 150,000 times greater than the sun. And if we include all of the energy consumed outside of our bodies in our global civilization, then many humans today achieve energy density flows millions of times greater than the sun.

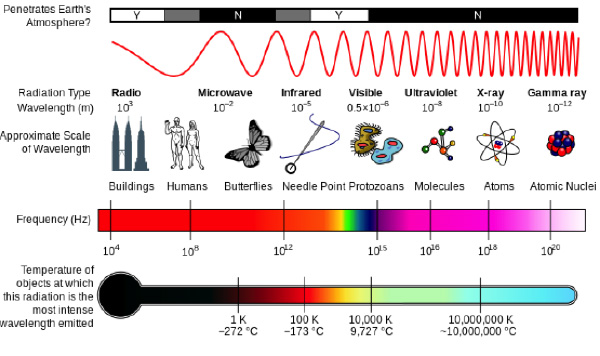

4. Electromagnetic Radiation: Electromagnetism governs almost all of the phenomena that we encounter in daily life. Negatively charged electrons are bound by electromagnetic waves into orbitals around positively charged atomic nuclei. Atoms combine into complex molecules through electromagnetic geometries and preferences. All chemistry, and therefore all biology, is governed by electromagnetic forces. The ATP molecules in your cells, the neurons in your brain, the gasoline burning in your car, the food you eat, and all the electronic devices in your life--from the light bulb to the Internet--are electromagnetic.

The entire spectrum of electromagnetic radiation goes from radio waves at one end, through microwave, infrared, visible, ultraviolet, and x-ray to gamma radiation at the other end, but our human eyes have evolved to see only a small range of visible light.

Electromagnetic radiation is central to all of the prosthetic "seeing" devices of science and technology -- from radio telescopes to electron microscopes. The tools by which we see, hear, touch, taste, smell, and understand the universe of the very small and the very big, the very hot and the very cold, the very fast and the very slow, all utilize the electromagnetic effect in their technologies of perception. The spectrum of electromagnetic radiation is the fourth axis in the Great Matrix of Being.

Image: Electromagnetic Spectrum Wiki Media

5. Emergent Complexity: Here we need to appeal to informed intuition and induction, rather than some discreet, measurable qualia in nature.

The epic narrative of Big History typically orients around eight thresholds of emergent complexity. For instance, the creation of the heavy elements in the stellar foundries from which we derive the elements of the periodic table was a threshold of emergent complexity necessary for complex chemistry to later evolve. When complex chemistry catalyzed life, we saw again something new and different. And when the evolution of plants and animals gave rise to species with a central nervous system, complex brains, oppositional thumbs, vocal chords, language, tool-making, and collective learning, something new emerged again in the universe, at least on one small planet.

It is important to emphasize that emergent complexity requires lower levels of complexity to exist and function. Higher orders of complexity are built bottom-up, though emergent properties cannot be fully explained from below. With thresholds of emergent complexity, the Matrix is not simply a coordinate system of reality, but now also an epic narrative of becoming.

The four dimensions in the Great Matrix of Being give us four ways of measuring reality -- by time, by scale, by energy density flow, and by thresholds of emergent complexity. All phenomena can be located within this Matrix.

But we might postulate another axis in the Matrix: a hierarchy of consciousness. The brain-mind is an emergent phenomena and potentially scalable. A roundworm in a neuroscience lab might have only a few hundred nerve cells, while a human brain has hundreds of billions of nerve cells. Surely, there are objective differences in brain-mind complexity throughout the animal kingdom. Counting nerve cells alone, however, does not really give us an adequate measure of brain-minds because brain-minds require bodies and metabolism, vocal chords and oppositional thumbs, and an enriching social and natural environment, in order to realize their potentials. Perhaps someday we may have a robust measure of consciousness that will allow us to compare dogs with cuttlefish, elephants with birds, and smart phones with smart people.

What is important to note about the Matrix is that humans are not at the top of the hierarchies, but somewhere in the middle. Complexity thrives when it is not too hot and not too cold, not too big and not too small. Different entities have different Goldilocks niches within the Matrix. The human niche is particularly favored in the Matrix for the time being--each of us a nexus of causal relationships (physical, biological, social, economic, psychological, mental), realizing extraordinary energy density flows, intensities of experience, and accelerating transformations in the modern period.

In our drive toward specialization and division of labors, we rarely reflect on these natural hierarchies and what they might mean for our understanding of science, self, and the sacred. Any concept of God adequate for modern science, for instance, must also be reconstructed in light of the Great Matrix of Being. An anthropomorphic monarch sitting on heavenly thrones no longer make sense.

"We exist in a bizarre combination of Stone Age emotions, medieval beliefs, and god-like technology," observed E.O. Wilson. To understand this schizophrenic state of affairs and transform it into something more wholesome, we need to understand how the Matrix actually works on different scales and perspectives. We need to see the emergent complexity of chemistry and cell biology. We need to understand the ubiquity of electromagnetism. We need to take account of the energy that flows through our daily lives. It is by consciously doing so that we extend our own being to the furthest edges of the universe and realize our fullest potential.

The bio-social-physical You and Me are never outside the Matrix, but in this scientific and philosophical exercise we seem to stand away, looking down on the Matrix from above. So far as we know, no other entity in the universe has achieved this capacity, and it is in this domain that humans are no longer middling creatures of the Matrix. Our self-transcendence, realized especially through the progress in science, is a super and completely natural emergent phenomena. We come to understand the Matrix from the inside out, though the Matrix knows nothing of us.

~ This article was originally published on Huffington Post Religion on 2/26/2013

Listen/View

Listen/View