Into the Landscape of Genomic Evolution

How the tools of genetic sequencing are changing the way we study the origins and development of life.

Over the past decade, a new way to study evolution has enabled scientists to investigate how life works and how it came to be, without needing to do experiments or work with plants, animals, or any other living thing. The landscape of DNA-sequencing data, which is pouring out of laboratories around the world, is providing an unparalleled source of new information that is helping researchers tackle questions about evolution. And the data is constantly expanding as thousands more bases of DNA are sequenced every second.

In this Seed audio podcast, journalist and ecologist John Whitfield meets the new genomic explorers who are asking questions that Darwin himself would have recognized and others he could never have known to ask.

Offering multiple perspectives from many fields of human inquiry that may move all of us toward a more integrated understanding of who we are as conscious beings.

Saturday, February 14, 2009

Seed - Into the Landscape of Genomic Evolution

In These Times - Forget Marriage—Civil Unions For All

I personally believe that marriage is a religious engagement, and as such, the government has no business being involved in who can or cannot be married. On the other hand, civil unions are legal agreements, and this is an area where each state can set their own standards, with the caveat that they cannot discriminate in any way (as provided for in the Constitution of the United States).

I've made this argument before, but now someone else is making it, and in a national magazine. BUT, I am not down with the full range that Allen is arguing for (incest type relationships should be forbidden, as well as underage unions - the abuse risks are too great to allow these types of unions).

Forget Marriage—Civil Unions For All

By Terry J. Allen

I believe fervently in the sanctity of marriage, and if you do, too, head immediately to your closest church, mosque, synagogue or flying spaghetti monster chapel, and sign up to procreate, cohabitate and copulate with a sex partner blessed by that holy institution.

But pass city hall and do not collect $200 in tax breaks. In fact, given the intrinsic rewards of sanctity, it’s pretty greedy to demand any secular perks from the state. Eternal life at the feet of the old white guy and his hench-angels should be prize enough.

Making your marriage sacred should be between you and your goddy thing.

Making your union legal, on the other hand, should be between you and state-guaranteed legal and human rights. And it should be available to any two people, gay or straight, in whatever configuration: Mother and son, grandparent and grandkid, mother and daughter, and best friends should all be able to form legal couples that enjoy the rights, privileges, financial benefits and responsibilities now assigned to marriage. (Calm down Rev. Rick: Only two people, no pets allowed.)

America’s current marriage system, even when it includes same-sex couples, inherently discriminates against millions of people who are not in a sexual relationship. (That many legal marriages are platonic only adds irony to injustice.) Ensuring equal rights for all requires relegating or elevating (however you look at it) marriage to the realm of religion. Kind of like christenings, bar mitzvahs and chicken sacrifice.

The state’s job, then, would be to assign benefits, if any, to couples, but not to define who can enter into coupledom. There is no rational, as opposed to religious, reason why any two people shouldn’t be able to form a civil union that carries the same rights as marriage: to pass on and inherit property, make decisions for the sick, visit inmates and get discounts on Carnival cruises.

Without the religious framework, joining civil, secular rights to heterosexual or even gay coupledom becomes bizarre. Think about it: To enjoy the tax and other benefits of marriage (or its gay stepchild, current civil unions), a couple is assumed to have consummated the deal with sex—with each other.

But why shouldn’t any practical or loving couple be able to form a unit and consummate it with anything they choose? A night at the opera, a day at the races, a signature on a will?

Irrational fear and religion (but I repeat myself) underlie the state’s stance that it can assign secular rights to a sacred institution designed for sexual partners—and can exclude platonic couples. But really, would the legal right to shared Social Security benefits so excite two heterosexual women that they would turn lesbian? Would allowing two brothers to share medical benefits inspire them to acts of incest?

Or would, God forbid, too many people get health benefits and share incomes and resources?

Tradition is another bulwark against change. But even traditions that appear carved in stone or mandated by God evolve over time like Darwin’s finches. “Traditional” marriage used to be a business contract between families. It legitimized procreative sex and formalized property and inheritance. It was often polygamous and included child spouses. Men’s conjugal rights included rape and the rule of thumb—the right to beat a wife with a stick no thicker than his thumb.

Gradually, many societies embraced an ideal of romantic love that undermined arranged marriages, while women’s increasing legal, sexual and financial independence undercut marriage as society’s mechanism of choice for promoting the lawful and peaceful transition of property.

Today, people—including women—can leave their property to whomever they wish, and they can rely on DNA tests rather than the friable sanctity of marriage if they wish to base their decisions on bloodlines. But they still cannot define the most legally significant relationships of their lives.

Rather than simply fighting the Religious Right’s campaign to stop gay marriage and weaken the church-state divide, progressives could take a more radical approach. Gay and straight, they could demand an unbridgeable chasm between state and mate.

If you want a sanctified marriage, exchange vows at a religious institution that accepts you. Heaven and sanctified sex await.

But if you want that bond to be legal, wait in line at city hall with the farmer and his son, the grandmother and orphaned grandchild, the elderly widows, all of whom deserve better healthcare, joint property, fuss-free inheritance and the right to form a secular, civilized union.

Book TV: Jay Parini "Promised Land"

Author Jay Parini details the 13 books he believes most shaped America. They include Of Plymouth Plantation, The Federalist Papers, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, Uncle Tom's Cabin, and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Parini discusses his choices and their influence on American culture with Sam Tanenhaus, Editor, New York Times Book Review.Embedding is disabled, so go check it out (it's short).

Friday, February 13, 2009

Quotes from the "American Taliban"

These people are scary, and although many of them would have me deported or imprisoned for my views, what makes America a great nation (and I am not at all patriotic) is that they can publicly share their views, no matter how hateful and ignorant, and no one will deport them or imprison them. Why won't they extend that same consideration to others?

This kind of hatred is why the left is so intolerant of the religious right, which is its own kind of hatred. But sometimes, the only response to hatred is stamp it out, as best we can, without spilling blood.

Ann CoulterThere's much more where this came from.

"We should invade their countries, kill their leaders and convert them to Christianity. We weren't punctilious about locating and punishing only Hitler and his top officers. We carpet-bombed German cities; we killed civilians. That's war. And this is war."

"Not all Muslims may be terrorists, but all terrorists are Muslims."

"Being nice to people is, in fact, one of the incidental tenets of Christianity, as opposed to other religions whose tenets are more along the lines of 'kill everyone who doesn't smell bad and doesn't answer to the name Mohammed'"

Bailey Smith

"With all due respect to those dear people, my friend, God Almighty does not hear the prayer of a Jew."

Beverly LaHaye (Concerned Women for America)

"Yes, religion and politics do mix. America is a nation based on biblical principles. Christian values dominate our government. The test of those values is the Bible. Politicians who do not use the bible to guide their public and private lives do not belong in office."

Bob Dornan (Rep. R-CA)

"Don't use the word 'gay' unless it's an acronym for 'Got Aids Yet'"

David Barton (Wallbuilders)

"There should be absolutely no 'Separation of Church and State' in America."

David Trosch

"Sodomy is a graver sin than murder. – Unless there is life there can be no murder."

Fred Phelps (Westboro Baptist Church)

"If you got to castrate your miserable self with a piece of rusty barb wire, do it."

"Hear the word of the LORD, America, fag-enablers are worse than the fags themselves, and will be punished in the everlasting lake of fire!"

"You telling these miserable, Hell-bound, bath house-wallowing, anal-copulating fags that God loves them!? You have bats in the belfry!"

"American Veterans are to blame for the fag takeover of this nation. They have the power in their political lobby to influence the zeitgeist, get the fags out of the military, and back in the closet where they belong!"

"Not only is homosexuality a sin, but anyone who supports fags is just as guilty as they are. You are both worthy of death."

Gary Bauer (American Values)

"We are engaged in a social, political, and cultural war. There's a lot of talk in America about pluralism. But the bottom line is somebody's values will prevail. And the winner gets the right to teach our children what to believe."

Gary North (Institute for Christian Economics)

"The long-term goal of Christians in politics should be to gain exclusive control over the franchise. Those who refuse to submit publicly to the eternal sanctions of God by submitting to His Church's public marks of the covenant–baptism and holy communion–must be denied citizenship."

"This is God's world, not Satan's. Christians are the lawful heirs, not non-Christians."

Gary Potter (Catholics for Christian Political Action)

"When the Christian majority takes over this country, there will be no satanic churches, no more free distribution of pornography, no more talk of rights for homosexuals. After the Christian majority takes control, pluralism will be seen as immoral and evil and the state will not permit anybody the right to practice evil."

George Bush Sr. (President of the United States)

"I don't know that atheists should be considered citizens, nor should they be considered patriots. This is one nation under God."

George W. Bush (President of the United States)

"God told me to strike at al Qaida and I struck them, and then he instructed me to strike at Saddam, which I did, and now I am determined to solve the problem in the Middle East. If you help me I will act, and if not, the elections will come and I will have to focus on them."

"Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists."

"This crusade, this war on terrorism is going to take a while."

Henry Morris (Founder, Institute for Creation Research, died 2006)

"When science and the Bible differ, science has obviously misinterpreted its data."

J. B. Stoner (White Supremacist) (1924 - 2005)

"We had lost the fight for the preservation of the white race until God himself intervened in earthly affairs with AIDS to rescue and preserve the white race that he had created.... I praise God all the time for AIDS."

"AIDS is a racial disease of Jews and Niggers, and fortunately it is wiping out the queers. I guess God hates queers for several reasons. There is one big reason to be against queers and that is because every time some white boy is seduced by a queer into becoming a queer, means his white bloodline has run out."

James Dobson (Focus on the Family)

"Those who control the access to the minds of children will set the agenda for the future of the nation and the future of the western world."

"State Universities are breeding grounds, quite literally, for sexually transmitted diseases (including HIV), homosexual behavior, unwanted pregnancies, abortions, alcoholism, and drug abuse."

"Today's children... They're damned. They're gone."

Upaya Zen Center - Zen Brain 4

Zen Brain 4

Zen Brain with Richard Davidson, Ph.D.

Recorded on: January 9, 2009

Posted on: February 12, 2009

Speaker: Richard Davidson, Ph.D.

Show: 116

Dr. Davidson describes his recent electroencephalographic and neuroimaging studies of long-term Buddhist practitioners, and of persons who receive short-term training in mindfulness-based stress reduction. He explores the ways in which complexity theory may help in understanding the patterns of brain physiology he has observed, and the development of compassion in long-term meditators.

Susan Blackmore - Ten Zen Questions

Ten Zen Questions

February 12, 2009; Posted by Aaron Lackowski

UK psychologist Susan Blackmore is a highly sought-after expert on a recurring theme in Buddhist inquiry: consciousness. She is the author of Consciousness: An Introduction, Conversations on Consciousness, A Very Short Introduction to Consciousness, and the acclaimed book The Meme Machine.

We’ve just gotten our hands on her latest project, a synthesis of philosophy and practice entitled Ten Zen Questions. The stumpers Blackmore poses are not easy to get a handle on, but that is exactly the point: Am I conscious now? What was I conscious of a moment ago? When are you? What happens next? Her chapter-length responses to each are firmly rooted in the dirt of personal experience; anecdotes from life on and off the cushion lay the groundwork for an engagement with these mental puzzles.

Drawing on an extensive knowledge of brain science, Blackmore enters the “Buddhism as science” discussion from an informed perspective, and her challenges are compelling:

Science needs clear thinking, and scientists have to construct logical arguments, think critically, ask awkward questions, and find the flaws in other people’s arguments, but somehow they are expected to do this all without any kind of preliminary mental training. Certainly science courses do not begin with a session on calming the mind.

[...]

[This book is] my attempt to see whether looking directly into one’s own mind can contribute to a science of consciousness. Bringing personal experience into science is positively frowned upon in most of science; and with good reason. If you want to find out the truth about planetary motion, the human genome or the effectiveness of a new medicine, then personal beliefs are a hindrance not a help. However, this may not be true of all science. As our growing understanding of the brain brings us ever closer to facing up to the problem of consciousness, it may be time for the scientist’s own experience to be welcomed as part of the science itself, if only as a guide to theorising or to provide a better description of what needs to be explained.

Be sure to check the book out. And while you’re thinking about the above quote, remember one thing about scientific questions:

They seem to require both the capacity to think and the capacity to refrain from thinking.

Integral Life - How to Deal with Disappointment in Your Spiritual Teachers

In the clip, Tami Simon (owner of Sounds True) and Ken Wilber talk about this topic. The Ken suggests we might experience the flawed teacher's wisdom more fully when we recognize their imperfection.

Here is a bit of the blog post that accompanied this video:How to Deal with Disappointment in Your Spiritual Teachers

Tami Simon shares her experiences of being painfully disappointment by various spiritual teachers, as well as her own personal methods of working with this disappointment. What do we do when our spiritual guides don't quite measure up to our own expectations of them? Can recognizing their limitations actually help free the wisdom the have to offer us?

Read more of this post.Written by Corey W. deVos

By virtue of running a business like Sounds True, which has produced a litany of audio interviews with a staggering amount of today's heaviest-hitting spiritual teachers, Tami has had plenty of opportunities to get to know many of the world's most extraordinary teachers in very deep and profound ways. As she mentions in the interview, when there is a business contract sitting on the table between herself and some of these teachers, she is often exposed to a side of them that many of their own students aren't—a side that occasionally appears to be incongruous with the lofty perceptions that surround them. Rather than being the perfect vehicles of liberation they are often made out to be, Tami has found many of these teachers to be anything but perfect. She has been exposed to their full humanness, and finds that they possess many of the same relative foibles, flaws, and idiosyncrasies that so many of us are subject to. Sometimes this experience can be endearing, but many times it is painfully disappointing—especially when the teachers seem to be so unaware of their limitations, parading their spiritual realization in such a way that tries to mask their own human twistedness.

This sort of disappointment has been felt by a great number of people somewhere along their spiritual path, who have at some point become suddenly aware of their own teacher's imperfections, in ways that can violently undercut the reverence and spiritual connection they feel with them. Sometimes students are disappointed when they hold on to the naive belief that spirituality is some sort of magical elixir, which, when done right, promises to make us happy all the time and cure all of our life's ailments. And when flaws in our spiritual teachers are inevitably discovered, it must be because they are doing something wrong, and are therefore in no position to teach us anything. Other times, this disillusionment is simply a result of the quixotic projections many students unfairly impose upon their teachers—expectations that, since spiritual teachers are here as representatives of absolute perfection, they must themselves be absolutely perfect. And when it is discovered that these teachers still eat, use the bathroom, and have sex, they are immediately stripped of their demi-god status and cast out of our idealized heavens.

[Note: I have some misgivings about this post, considering the re-emergence of Marc Gafni (a brilliant, charismatic man with a long history of sexual misconduct involving students) into the integral community. Seems to me a bit of "paving the way" to embrace someone who had been rightfully removed from the community.]

New Scientist - Born Believers: How Your Brain Creates God

Oh, how those science types love to reduce all subjective experience, and especially the experience of God or Spirit, to some collection of neurological functions. What they seem to miss, however, is the possibility that the experience actually precedes the neurological element. But then, that might mean that there is something more than a materialist understanding of the world.

Oh, how those science types love to reduce all subjective experience, and especially the experience of God or Spirit, to some collection of neurological functions. What they seem to miss, however, is the possibility that the experience actually precedes the neurological element. But then, that might mean that there is something more than a materialist understanding of the world.Born believers: How your brain creates God

04 February 2009 by Michael Brooks - Magazine issue 2694. Subscribe and get 4 free issues.

WHILE many institutions collapsed during the Great Depression that began in 1929, one kind did rather well. During this leanest of times, the strictest, most authoritarian churches saw a surge in attendance.

This anomaly was documented in the early 1970s, but only now is science beginning to tell us why. It turns out that human beings have a natural inclination for religious belief, especially during hard times. Our brains effortlessly conjure up an imaginary world of spirits, gods and monsters, and the more insecure we feel, the harder it is to resist the pull of this supernatural world. It seems that our minds are finely tuned to believe in gods.

Religious ideas are common to all cultures: like language and music, they seem to be part of what it is to be human. Until recently, science has largely shied away from asking why. "It's not that religion is not important," says Paul Bloom, a psychologist at Yale University, "it's that the taboo nature of the topic has meant there has been little progress."

The origin of religious belief is something of a mystery, but in recent years scientists have started to make suggestions. One leading idea is that religion is an evolutionary adaptation that makes people more likely to survive and pass their genes onto the next generation. In this view, shared religious belief helped our ancestors form tightly knit groups that cooperated in hunting, foraging and childcare, enabling these groups to outcompete others. In this way, the theory goes, religion was selected for by evolution, and eventually permeated every human society (New Scientist, 28 January 2006, p 30)

The religion-as-an-adaptation theory doesn't wash with everybody, however. As anthropologist Scott Atran of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor points out, the benefits of holding such unfounded beliefs are questionable, in terms of evolutionary fitness. "I don't think the idea makes much sense, given the kinds of things you find in religion," he says. A belief in life after death, for example, is hardly compatible with surviving in the here-and-now and propagating your genes. Moreover, if there are adaptive advantages of religion, they do not explain its origin, but simply how it spread.

An alternative being put forward by Atran and others is that religion emerges as a natural by-product of the way the human mind works.

That's not to say that the human brain has a "god module" in the same way that it has a language module that evolved specifically for acquiring language. Rather, some of the unique cognitive capacities that have made us so successful as a species also work together to create a tendency for supernatural thinking. "There's now a lot of evidence that some of the foundations for our religious beliefs are hard-wired," says Bloom.

Much of that evidence comes from experiments carried out on children, who are seen as revealing a "default state" of the mind that persists, albeit in modified form, into adulthood. "Children the world over have a strong natural receptivity to believing in gods because of the way their minds work, and this early developing receptivity continues to anchor our intuitive thinking throughout life," says anthropologist Justin Barrett of the University of Oxford.

So how does the brain conjure up gods? One of the key factors, says Bloom, is the fact that our brains have separate cognitive systems for dealing with living things - things with minds, or at least volition - and inanimate objects.

This separation happens very early in life. Bloom and colleagues have shown that babies as young as five months make a distinction between inanimate objects and people. Shown a box moving in a stop-start way, babies show surprise. But a person moving in the same way elicits no surprise. To babies, objects ought to obey the laws of physics and move in a predictable way. People, on the other hand, have their own intentions and goals, and move however they choose.

Mind and matter

Bloom says the two systems are autonomous, leaving us with two viewpoints on the world: one that deals with minds, and one that handles physical aspects of the world. He calls this innate assumption that mind and matter are distinct "common-sense dualism". The body is for physical processes, like eating and moving, while the mind carries our consciousness in a separate - and separable - package. "We very naturally accept you can leave your body in a dream, or in astral projection or some sort of magic," Bloom says. "These are universal views."

There is plenty of evidence that thinking about disembodied minds comes naturally. People readily form relationships with non-existent others: roughly half of all 4-year-olds have had an imaginary friend, and adults often form and maintain relationships with dead relatives, fictional characters and fantasy partners. As Barrett points out, this is an evolutionarily useful skill. Without it we would be unable to maintain large social hierarchies and alliances or anticipate what an unseen enemy might be planning. "Requiring a body around to think about its mind would be a great liability," he says.

Useful as it is, common-sense dualism also appears to prime the brain for supernatural concepts such as life after death. In 2004, Jesse Bering of Queen's University Belfast, UK, put on a puppet show for a group of pre-school children. During the show, an alligator ate a mouse. The researchers then asked the children questions about the physical existence of the mouse, such as: "Can the mouse still be sick? Does it need to eat or drink?" The children said no. But when asked more "spiritual" questions, such as "does the mouse think and know things?", the children answered yes.

Default to god

Based on these and other experiments, Bering considers a belief in some form of life apart from that experienced in the body to be the default setting of the human brain. Education and experience teach us to override it, but it never truly leaves us, he says. From there it is only a short step to conceptualising spirits, dead ancestors and, of course, gods, says Pascal Boyer, a psychologist at Washington University in St Louis, Missouri. Boyer points out that people expect their gods' minds to work very much like human minds, suggesting they spring from the same brain system that enables us to think about absent or non-existent people.

The ability to conceive of gods, however, is not sufficient to give rise to religion. The mind has another essential attribute: an overdeveloped sense of cause and effect which primes us to see purpose and design everywhere, even where there is none. "You see bushes rustle, you assume there's somebody or something there," Bloom says.

This over-attribution of cause and effect probably evolved for survival. If there are predators around, it is no good spotting them 9 times out of 10. Running away when you don't have to is a small price to pay for avoiding danger when the threat is real.

Again, experiments on young children reveal this default state of the mind. Children as young as three readily attribute design and purpose to inanimate objects. When Deborah Kelemen of the University of Arizona in Tucson asked 7 and 8-year-old children questions about inanimate objects and animals, she found that most believed they were created for a specific purpose. Pointy rocks are there for animals to scratch themselves on. Birds exist "to make nice music", while rivers exist so boats have something to float on. "It was extraordinary to hear children saying that things like mountains and clouds were 'for' a purpose and appearing highly resistant to any counter-suggestion," says Kelemen.

In similar experiments, Olivera Petrovich of the University of Oxford asked pre-school children about the origins of natural things such as plants and animals. She found they were seven times as likely to answer that they were made by god than made by people.

These cognitive biases are so strong, says Petrovich, that children tend to spontaneously invent the concept of god without adult intervention: "They rely on their everyday experience of the physical world and construct the concept of god on the basis of this experience." Because of this, when children hear the claims of religion they seem to make perfect sense.

Our predisposition to believe in a supernatural world stays with us as we get older. Kelemen has found that adults are just as inclined to see design and intention where there is none. Put under pressure to explain natural phenomena, adults often fall back on teleological arguments, such as "trees produce oxygen so that animals can breathe" or "the sun is hot because warmth nurtures life". Though she doesn't yet have evidence that this tendency is linked to belief in god, Kelemen does have results showing that most adults tacitly believe they have souls.

Boyer is keen to point out that religious adults are not childish or weak-minded. Studies reveal that religious adults have very different mindsets from children, concentrating more on the moral dimensions of their faith and less on its supernatural attributes.

Even so, religion is an inescapable artefact of the wiring in our brain, says Bloom. "All humans possess the brain circuitry and that never goes away." Petrovich adds that even adults who describe themselves as atheists and agnostics are prone to supernatural thinking. Bering has seen this too. When one of his students carried out interviews with atheists, it became clear that they often tacitly attribute purpose to significant or traumatic moments in their lives, as if some agency were intervening to make it happen. "They don't completely exorcise the ghost of god - they just muzzle it," Bering says.

The fact that trauma is so often responsible for these slips gives a clue as to why adults find it so difficult to jettison their innate belief in gods, Atran says. The problem is something he calls "the tragedy of cognition". Humans can anticipate future events, remember the past and conceive of how things could go wrong - including their own death, which is hard to deal with. "You've got to figure out a solution, otherwise you're overwhelmed," Atran says. When natural brain processes give us a get-out-of-jail card, we take it.

That view is backed up by an experiment published late last year (Science, vol 322, p 115). Jennifer Whitson of the University of Texas in Austin and Adam Galinsky of Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, asked people what patterns they could see in arrangements of dots or stock market information. Before asking, Whitson and Galinsky made half their participants feel a lack of control, either by giving them feedback unrelated to their performance or by having them recall experiences where they had lost control of a situation.

The results were striking. The subjects who sensed a loss of control were much more likely to see patterns where there were none. "We were surprised that the phenomenon is as widespread as it is," Whitson says. What's going on, she suggests, is that when we feel a lack of control we fall back on superstitious ways of thinking. That would explain why religions enjoy a revival during hard times.

So if religion is a natural consequence of how our brains work, where does that leave god? All the researchers involved stress that none of this says anything about the existence or otherwise of gods: as Barratt points out, whether or not a belief is true is independent of why people believe it.

It does, however, suggests that god isn't going away, and that atheism will always be a hard sell. Religious belief is the "path of least resistance", says Boyer, while disbelief requires effort.

These findings also challenge the idea that religion is an adaptation. "Yes, religion helps create large societies - and once you have large societies you can outcompete groups that don't," Atran says. "But it arises as an artefact of the ability to build fictive worlds. I don't think there's an adaptation for religion any more than there's an adaptation to make airplanes."

I don't think there's an adaptation for religion any more than there's an adaptation to make airplanesSupporters of the adaptation hypothesis, however, say that the two ideas are not mutually exclusive. As David Sloan Wilson of Binghamton University in New York state points out, elements of religious belief could have arisen as a by-product of brain evolution, but religion per se was selected for because it promotes group survival. "Most adaptations are built from previous structures," he says. "Boyer's basic thesis and my basic thesis could both be correct."

Robin Dunbar of the University of Oxford - the researcher most strongly identified with the religion-as-adaptation argument - also has no problem with the idea that religion co-opts brain circuits that evolved for something else. Richard Dawkins, too, sees the two camps as compatible. "Why shouldn't both be correct?" he says. "I actually think they are."

Ultimately, discovering the true origins of something as complex as religion will be difficult. There is one experiment, however, that could go a long way to proving whether Boyer, Bloom and the rest are onto something profound. Ethical issues mean it won't be done any time soon, but that hasn't stopped people speculating about the outcome.

It goes something like this. Left to their own devices, children create their own "creole" languages using hard-wired linguistic brain circuits. A similar experiment would provide our best test of the innate religious inclinations of humans. Would a group of children raised in isolation spontaneously create their own religious beliefs? "I think the answer is yes," says Bloom.

Read our related editorial: The credit crunch could be a boon for irrational belief

God of the gullibile

In The God Delusion, Richard Dawkins argues that religion is propagated through indoctrination, especially of children. Evolution predisposes children to swallow whatever their parents and tribal elders tell them, he argues, as trusting obedience is valuable for survival. This also leads to what Dawkins calls "slavish gullibility" in the face of religious claims.

If children have an innate belief in god, however, where does that leave the indoctrination hypothesis? "I am thoroughly happy with believing that children are predisposed to believe in invisible gods - I always was," says Dawkins. "But I also find the indoctrination hypothesis plausible. The two influences could, and I suspect do, reinforce one another." He suggests that evolved gullibility converts a child's general predisposition to believe in god into a specific belief in the god (or gods) their parents worship.

Michael Brooks is a writer based in Lewes, UK. He is the author of 13 Things That Don't Make Sense (Profile)

Thursday, February 12, 2009

Tommy Lee: Buddhist?

From Awake in This Life:

You can read the whole interview at the Suicide Girls blog.Mötley Crüe’s Tommy Lee as Bodhisattva

Posted by Michael McAlister

Wow. I never would have guessed that Tommy Lee would be so concerned with spiders’ rights to “rock out.” I guess incarceration was helpful.

TOMMY LEE: I practice Buddhism, and I definitely believe there’s someone higher and greater than all of us out there, you know…It was a couple of years ago. I was in jail for an entire summer, like four, five months, and I started reading a couple of books on it, and I was like, “Wow!” It’s really amazing you know. It’s good stuff.

QUESTION: So what about Buddhism have you been able to apply to your life? And what about it has really helped you?

TOMMY LEE: It’s just compassion really, more than anything. Like, if you see a little spider on the ground, you don’t smash him, you grab him and put him outside and let him go rock out. I think, it’s just compassion for everything, all things.All things. Good. Don’t smash things. This also goes for your ex-wife, Pamela… despite her obvious, ahem, unnatural attributes. No smashing anything.

Seed - The Evolution of Life in 60 Seconds

The Evolution of Life in 60 Seconds

A video experiment in scale, condensing 4.6 billion years of history into a minute.

The Evolution of Life in 60 Seconds is an experiment in scale: By condensing 4.6 billion years of history into a minute, the video is a self-contained timepiece. Like a specialized clock, it gives one a sense of perspective. Everything — from the formation of the Earth, to the Cambrian Explosion, to the evolution of mice and squirrels — is proportionate to everything else, displaying humankind as a blip, almost indiscernible in the layered course of history.

Each event in the Evolution of Life fades gradually over the course of the minute, leaving typographic traces that echo all the way to the present day. Just as our blood still bears the salt water of our most ancient evolutionary ancestors.

Produced by Claire L. Evans.

Upaya Dharma Podcasts - Zen Brain

Zen Brain 1

January 8th, 2009Recorded on: January 8th, 2009

Posted on: February 2nd, 2009

Speaker: Sandra Blakeslee

Show: 113Science journalist and New York Times contributor Sandra Blakeslee provides an overview of how recent developments in neuroscience have changed the way we view the impact of various practices, including meditation, upon brain structure and function.

Zen Brain 1 [75:22m]: Hide Player | Play in Popup | Download

* * *Zen Brain 2

January 8th, 2009Recorded on: January 8th, 2009

Posted on: February 9, 2009

Speaker: Richard Davidson, Ph.D.

Show: 114

Neuroscientist Richard Davidson provides an introduction to brain systems that may be relevant to meditation. This presentation gives an orientation to neurophysiology and lays the foundation for Dr. Davidson’s second presentation which discusses the relationship between the brain and meditation.Zen Brain 2 [60:24m]: Hide Player | Play in Popup |

* * *Zen Brain 3

January 8th, 2009Zen Brain Question and Answer Session #1

Recorded on: January 8, 2009

Posted on: February 11, 2009

Speaker: Presenters and Audience

Show: 115The presenters read and answer questions written by the audience. Topics include the role of meditation in the scientific workplace; trauma, PTSD and resilience in relation to meditation; and whether meditators have less of a chance of developing dementia or Alzheimer’s.

Zen Brain 3 [63:30m]: Hide Player | Play in Popup | Download

The Skeptic - Doubting Altruism

Read the whole article.One of the knottier problems in evolutionary theory is altruism, because if you sacrifice yourself for someone else it would seem that you are helping someone else get their genes into the next generation at the cost of your own evolutionary heritage, and thus true altruism would seem to be anti- or non-Darwinian. And yet there are examples of animals (including human animals) who make such sacrifices. How do evolutionary biologists explain this mystery? There are several interesting answers that have been proposed since Darwin's time.

In this week’s eSkeptic, our regular contributor Kenneth Krause reviews the latest research on altruism, most notably that of primate research in controlled experiments in which both monkeys and apes are given choices to cooperate or compete against game partners in exchange scenarios, with implications for human research in this area.

Krause is contributing science editor for the Humanist and books editor for Secular Nation. He has recently contributed to Skeptical Inquirer, Free Inquiry, Skeptic, Truth Seeker, Freethought Today, Wisconsin Lawyer, and Wisconsin Political Scientist as well.

Doubting Altruism

New research casts a skeptical eye

on the evolution of genuine altruismby Kenneth W. Krause

As we soar into an inspiring new era of genomics, genetic manipulation, and, potentially, the directed evolution of our own species, naturalists urge us to remain partially grounded — to keep digging for long-buried evidence of key pre-historical developments. In so doing, however, the world’s leading anthropologists and primatologists have immersed themselves in a now-roiling debate over the origins of human morality in general and altruism in particular.

Some say that altruism — sometimes referred to as “other-regarding preferences” or “unsolicited prosociality” — is nothing more than a veneer, a cultural innovation humans alone have achieved in order to collectively restrain each individual’s natural proclivity to serve only herself, her close genetic relatives, and those who have demonstrated an adequate inclination to reciprocate to her eventual benefit. For these folks, no act can be characterized as wholly unselfish.

Others argue that altruism is more primitive than culture and, in fact, considerably more ancient than the human species itself. Other-regarding preferences, they say, are deeply innate, predating even the phylogenetic split that occurred six million years ago among the common ancestors of chimps and bonobos on the one hand and all species of hominid on the other. According to this camp’s credo, selflessness is as natural as appetite.

One line of experiments has confronted the issue directly, inquiring whether non-human primates will seize opportunities to assist others. In 2005, for example, UCLA anthropologist Joan Silk and others chose 18 chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) as the subjects of two such experiments, conducted in Louisiana and Texas.1 Chimps are among the primates most likely to exhibit unsolicited prosocial behavior, they reasoned, because in the wild they regularly hunt, patrol, and mate-guard cooperatively.

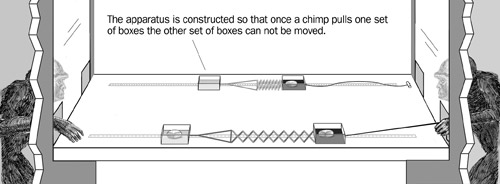

In each study, subject chimps were allowed to deliver food to other chimps, or “conspecifics,” at no cost to themselves. The test apparatuses provided each confined subject with two options — the 1/0 choice where it could acquire food only for itself, and the 1/1 choice where it could obtain food for both itself and its separately caged partner. As an essential control, acting chimps were given the same options with no partners present (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A test apparatus providing a subject with two options: acquire food only for itself (1/0), or obtain food for both itself and its separately caged partner (1/1).

Silk’s team predicted that if chimps are truly altruistic they should choose the 1/1 option more often than the 1/0 option when a conspecific is there to benefit. But that wasn’t the case. In Louisiana, not one of the seven subjects chose the 1/1 option significantly more often when partnered. In Texas, the remaining 11 actors went with both the 1/1 and the 1/0 option an average of only 48 percent of the time when another chimp was present.

“The absence of other-regarding preferences in chimpanzees,” the authors inferred, “may indicate that such preferences are a derived property of the human species tied to sophisticated capacities for cultural learning, theory of mind, perspective taking and moral judgment.” Nevertheless, Silk’s team remained open to the prospect that altruism might be detected among primates that, in some crucial ways, were even more cooperative than chimps. We will consider that possibility later.

Altruism’s Alter-Ego

A closely related line of experiments has tackled the same issue from a different direction, asking instead whether primates display a rudimentary sense of fairness in some form of “inequity aversion” (IA). If an animal reacts negatively to its own relative overcompensation, we say it has demonstrated some sensitivity to “advantageous inequity.” If it merely responds to a conspecific’s superior gain, on the other hand, the animal has shown aversion only to “disadvantageous inequity.”

The former inclination probably evolved after (and, morally speaking, is emphatically more advanced than) the latter because an animal sensitive to its own advantage can demonstrate not only an egocentric expectation of how it should be treated, but also a communal expectation of how all members of its species should be treated. In either case, if test subjects attempt to restore equity by sacrificing their own gains — even if only to simultaneously and unceremoniously deny superior gains to their luckier partners — according to many (but not all) researchers, they have nonetheless acted altruistically.

In 2003, Emory University primatologists Sarah Brosnan and Frans de Waal developed token exchange experiments where tufted capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) were measured for their reactions to situations in which their partners received greater food rewards.2 In the end, shortchanged subjects proved less likely to complete exchanges for identical tokens, and withdrew even more frequently when their partners received prizes for no tokens at all. These now-classic results have been widely interpreted as formidable evidence of disadvantageous IA in primates.

Two years later, Brosnan, de Waal, and Hillary Schiff released the outcomes of a similar study of adult chimpanzees.3 In order to distinguish the effects of social alignment, the team chose four animals that had lived continuously in pairs and 16 others that had been housed together at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center in Atlanta, Georgia for either 30 years or eight years prior to testing. As in the 2003 experiment, subjects were given tokens — in this case, rather useless and nondescript chunks of white PVC pipe — which they had been trained to return for either cucumber slices (the low-value reward) or grapes (the high-value reward).

During the inequity test, examiners initially allowed the partner chimps to exchange for a juicy, delicious grape — while eager subjects observed, of course — and then offered the subjects a relatively dry and no doubt disappointing cucumber slice. The examiners diligently recorded the subjects’ reactions, noting whether they had accepted or rejected their prizes. Brosnan discovered first that, when the tables were turned, subjects did not react negatively when given a superior reward and, thus, were likely not averse to advantageous inequity. Whether such a finding actually distinguished chimpanzees from humans in any meaningful way, the authors noted, was questionable.

Second, according to Brosnan, the results confirmed that disadvantageous IA was “present and robust” among chimpanzees, although to significantly different degrees depending on each subject’s social history. Chimps that had lived in pairs or in relatively novel groups reacted most intensely, while animals from older, more tightly-integrated groups appeared more accepting of inequity — all of which could be entirely consistent with human predilections to either “make waves” or “go with the flow,” depending primarily on their social milieu. Tolerance of inequity, Brosnan suggested, may be more a function of group size and intimacy than either moral choice or any isolated cognitive factor. So by the end of 2005, very little if anything had been truly settled. The experiments would continue and become ever more creative and exacting, but the already muddied anthropological waters would grow more cluttered and murkier still.

Wild River Review - Ask the Philosopher: Can We Say What We Mean?

Ask the Philosopher:

Can We Say What We Mean?

by William Cole-Kiernan

Thing 1 and Thing 2, Dr. Seuss

“That’s not what I said.”

“But, that’s what I heard.”

“What you heard is not what I meant.”

All of us have had similar exchanges. And yet, we often ask ourselves, why does this happen? Why the misunderstanding? The obvious answer is that either the person who was speaking wasn’t clear, or we weren’t listening carefully.

But, if the speaker was clear and we were listening, we have just encountered a deeper source of confusion. To understand this deeper level, we have to ask how is it possible to have meaning in our lives at all? How do we recognize meaning?

Meaning is found in our capacity to formulate, use, and understand symbols. In terms of language, a symbol is not the thing itself, but a verbal or written stand-in for that something. When we think of meaning this way, it becomes obvious that the word dog is not something we can pet. The word house is not something we can live in. Rather, words are a way of naming things without requiring the thing’s actual presence.

This gives the extraordinary option of me speaking about an elephant or a tiger, and you knowing what I mean without having to go the zoo or the jungle and tracking down elephants and tigers in the flesh.

Things get much more complicated when we move beyond easily recognizable objects and attempt to communicate about “things” like justice, love, beauty, truth, reality, feelings, knowledge and a whole host of other difficult abstractions that are not so clear and obvious in their meanings as dogs, houses, elephants, and tigers. When we talk in more intangible domains, communicating clearly is a more difficult process. Since, we can’t see into anyone’s head, a major source of confusion is how we experience our lives and how we communicate that experience.

I grew up near the Atlantic Ocean, and if I attempt to communicate what an ocean is like with someone from Kansas – who grew up amidst wheat fields and has never been to the ocean - their experience of listening and my experience of telling will be dramatically different. If I try to communicate about the seasonal “moods” of the ocean, the angry gray of a winter storm, for example, my midwestern friend may have difficulty following my train of thought, or even lose interest. If she has experiential insight about her wheat fields, she may lose me in the telling. But, if, in our sharing of experience, we communicate the vastness of the ocean and wheat fields, we may have achieved the elusive goal of saying what we men and being understood.

Human beings can only fully communicate with each other when we have shared experiences. And where our experiences diverge, so too will the mutuality and clarity of our meanings. Our ability to understand what each other means will be at risk.

Shared experience is the core necessity for understanding others’ meaning clearly. So, if what we mean emerges from the many contexts of our experience, we need to be careful how we tell our stories.

And if we don’t understand what our friend is telling us, we may wish to reframe our questions.

Thus, instead of asking, “What did you mean?”

Ask, “What is your experience?”

New Scientist - Why Do We Need Bras for Babies?

We have become obsessed with our bodies to degree that threatens to make some of us completely dysfunctional. In fact, with anorexia and muscle dysmorophia, as just two examples, we have become dysfunctional.

We have become obsessed with our bodies to degree that threatens to make some of us completely dysfunctional. In fact, with anorexia and muscle dysmorophia, as just two examples, we have become dysfunctional.The New Scientist looks at the issue.

Why do we need bras for babies?

- 10 February 2009 by Susie Orbach

- Magazine issue 2694. Subscribe and get 4 free issues.

See the related blog on our unhealthy obsession with our bodies

UNTIL very recently, we took our bodies for granted. We hoped we would be blessed with good health and, especially if we are female, good looks. Those who saw their body as their temple, or became magnificent athletes or iconic beauties, were the exception: we didn't expect to be like them. Like gifted scientists, historians, writers, directors, explorers or cooks, their talents extended and enhanced the world we lived in, but we didn't expect this beauty, prowess or brain power of ourselves.

Over the past 25 years, however, the notion of the empowered consumer, along with the workings of the diet, pharmaceutical, food, cosmetic surgery and style industries, and the affordability and availability of their products have made us view our bodies as something we can and should perfect. Looking good for ourselves will make us feel good, we believe.

These days, inboxes are full of invitations to enlarge penises or breasts, to purchase the pleasure and potency booster Viagra, to try the latest herbal or pharmaceutical preparation to lose weight. The exhortations have fooled spam filters and popular science pages, which, too, sing of implants and pills to augment body or brain and new methods of reproduction which bypass old biology.

Mothers can buy bra sets for their babies or rubber stilettos, little girls can go on the Miss Bimbo website to create a virtual doll, keep it "waif" thin with diet pills and buy it breast implants and facelifts. They are primed to be teenagers who will dream of new thighs, noses or breasts. Simultaneously, governments warn of an epidemic of obesity. Your body, these phenomena shout, is your canvas to be fixed, remade and enhanced. Join in. Enjoy. Be part of it. Be wary of it. But, above all, fix it.

So why is bodily contentment so hard to find? Why are body transformations, from sex change, to the drive to amputate good limbs, to cosmetic surgery, if not ubiquitous, then a growing part of public consciousness? Why is sex a must-have, wrapped up with performance and saturated with fantasy in a way that would have Freud reeling? What is the deep appeal of extreme makeover TV shows? What is wrong with our bodies as they are?

I wrote Bodies to explore these issues, issues I encounter as a practising psychotherapist and psychoanalyst. In my consulting room, I see the impact of calls for bodily transformations, enhancements and "perfectibility". People do not necessarily turn up with particular body troubles, but whatever their other emotional predicaments and conflicts, concern for the body is nearly always folded into them, as if it were perfectly ordinary to be telling a life story in which body dissatisfaction is central.

The notion that biology need no longer be destiny, and the belief in both the perfectible body and the idea we should relish or at least accede to improving our own all contribute to the idea of a progressively unstable sense of our body, a body which to an alarming degree is becoming a site of serious suffering.

To an alarming degree the body is becoming a site of serious suffering In an updating and democratising of the habit of the leisured classes of decorating themselves for amusement and as a marker of social standing, we are invited to take up this activity too. Something new is happening: our bodies are and have become a form of work. The body is turning from being the means of production to the production itself.

And where it was once women's bodies who were subjects of aggressive marketing, now men are targeted with steroids, sexual aids and specific masculine-oriented diet products. Children's bodies, too. Photographers now offer digitally enhanced baby and child photos - correcting smiles, putting in or removing toothy gaps, turning little girls into facsimiles of china dolls. Girlie-sexy culture now entrances more rather than fewer of us.

This democratic call for beauty wears an increasingly homogenised and homogenising form. While some people may be able to opt in, joyfully, a larger number cannot because the "democratic" idea has not extended to aesthetic variation but has, paradoxically, narrowed to a slim, westernised aesthetic, with pecs for men and big breasts for women. Body hatred is endemic in the west and is becoming one of its hidden exports.

What is very clear is that our old Descartian or Freudian conceptions of the body, with their differing emphases on separation of mind and body, or on understanding the mind through the body and especially through sexual activity, now seem inadequate. In our time, the body has become as complicated a place as sexuality was for Freud. Like sexuality, the body is shaped and misshaped by our earliest encounters with parents and carers, who contain the imperatives of the culture they grew up in, with its injunctions about how the body should appear and be attended to. Their sense of their own bodily deficiencies and strengths, their hopes and fears about physicality will play themselves out on the child. In my consulting room, their impact on the child's body sense and the subsequent adult's body sense becomes clear.

The growing number of physical transformations that people seek suggest that we need to marry developmental theory - how we understand the passage from infancy to adulthood - with the impact of contemporary social practices. Emerging sciences over the last 30 years have extended our understanding of what conflicts in the mind can do to the body. They have underlined the fact that there is now a crisis about the body itself, that many of us are acquiring a "false", unstable sense of our body.

This has made me question the whole notion of the body as something that unfolds organically according to its own genetic imprint from birth on, acted upon by the mind - and nutrition - only at key developmental stages. We need new theories of how we acquire a sense of body that are just as compelling as our existing theories of the mind. It may even be possible that, rather like the acquisition of language, there is only a relatively brief period in which we can acquire a stable sense of our bodies.

When we have understood more about the psychology of our bodies, we will be able to propose a richer theory of human development, with the body and mind in their proper relationship. We may also better understand how the visual cortex is affected by our image-saturated culture, and how this has led to a shrinking of the rich variety of human body expressions. Like the languages we lose fortnightly, we are almost doing away with body variety.

These are my clinical concerns and my theoretical propositions. Morally, I am pained and disquieted by the homogeneous visual culture promoted by industries that depend on the breeding of body insecurity and which then create "beauty terror" in so many.

It is only because it is so ordinary to be distressed about our bodies or body parts that we dismiss as "vanity" what are actually serious body problems. In fact, they constitute a hidden public health emergency - showing up only obliquely in the statistics on self harm, obesity and anorexia as the most visible and obvious signs of a wide-ranging body dis-ease.

The good news is this is not the only possible outcome of a digital and hypersaturated image culture. The tools which have given rise to a narrowing aesthetic could be redeployed to include the wide variety of bodies people actually have. Nor is it necessarily in the long-term interests of the style industries to promote a limited aesthetic. Indeed, it may benefit these same industries to celebrate diversity and variety and to make it their ethical aim to transform the body distress so many experience today.

Profile

Feminist psychotherapist Susie Orbach helped set up the Women's Therapy Centre in London. Among her clients was Diana, Princess of Wales, a bulimia sufferer. Orbach's Fat is a Feminist Issue was a bestseller. This essay is an edited extract from her new book, Bodies (Profile Books).

Tags: Psychology, brain, body, The New Scientist, Susie Orbach, bodily contentment, health, media, Bodies

Contributors:

Contributors: