From the

New York Times Magazine last weekend, an excellent article on the genius that is Jack White - on the eve of his first solo album, “

Blunderbuss,” due out April 24 (

preorder at Amazon for $9.99). I am definitely looking forward to the new album.

Jessica Dimmock/VII, for The New York Times

By JOSH EELLS

Published: April 5, 2012

In an industrial section of south-central Nashville, stuck between a homeless shelter and some railroad tracks, sits a little primary-colored Lego-block of a building with a Tesla tower on top. The inside holds all manner of curiosities and wonders — secret passageways, trompe l’oeil floors, the mounted heads of various exotic ungulates (a bison, a giraffe, a Himalayan tahr) as well as a sign on the wall that says photography is prohibited. This is the home of Third Man Records: the headquarters of Jack White’s various musical enterprises, and the center of his carefully curated world.

Jessica Dimmock/VII, for The New York Times

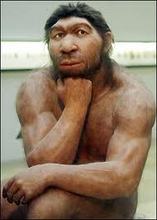

White rehearsing for a Raconteurs show in Nashville in September 2011.

Michael Lavine / Meg and Jack in their heyday, 2001.

Jessica Dimmock/VII, for The New York Times / Jack White (right) and his tour manager, Lalo Medina, in the musicians’ apartments at the United Record Pressing plant in Nashville.

“When I found this place” White said one day last April, “I was just looking for a place to store my gear. But then I started designing the whole building from scratch.” Now it holds a record store, his label offices, a concert venue, a recording booth, a lounge for parties and even a darkroom. “The whole shebang,” White said. It’s a one-stop creativity shop as designed by an imaginative kindergartner — a cross between Warhol’s Factory and the Batcave.

White, looking like a dandyish undertaker in a black suit and matching bowler, was in the record store, which doubles as a tiny Jack White museum. He is most famous as the singer for

the White Stripes, the red-and-white-clad Detroit duo that played a stripped-down, punked-up take on Delta blues; their gold and platinum records adorned the walls. Albums from Third Man artists, including White’s other bands, the Raconteurs and the Dead Weather, filled the racks. The décor reflected his quirky junk-art aesthetic: African masks and shrunken heads from New Guinea; antique phone booths and vintage Victrolas.

White is obsessive about color and meticulous in his attention to detail. Inside, the walls that face west are all painted red, and the ones that face east are all painted blue. The exterior, meanwhile, is yellow and black (with a touch of red). Before he made his living as a musician, White had an upholstery shop in Detroit, and everything related to it was yellow and black — power tools, sewing table, uniform, van. He also had yellow-and-black business cards bearing the slogan “Your Furniture’s Not Dead” as well as his company name, Third Man Upholstery. When he started the record label, he simply carried everything over. “Those colors sort of just mean work to me now.”

Roaming the hallways were several young employees, all color-coordinated, like comic-book henchmen. The boys wore black ties and yellow shirts; the girls wore black tights and yellow Anna Sui dresses. (There were also a statistically improbable number of redheads.) White stopped in front of one cute girl in bluejeans and Vans. “Can you guess which Third Man employee is getting fined $50 today?” he asked, smiling.

Some have called Third Man a vanity project, like the Beatles’ Apple Records or Prince’s Paisley Park. But White’s tastes are far more whimsical. He has produced records for the ’50s rockabilly singer Wanda Jackson; the Detroit shock rappers Insane Clown Posse; a band called Transit, made up of employees of the Nashville Metropolitan Transit Authority. (Their first single was called “C’mon and Ride.”) And gimmicks like Third Man’s Rolling Record Store, basically an ice-cream truck for records, show he’s as much a huckster as an artist.

“I’m trying to get somewhere,” White, who is 36, said, reclining in his tin-ceilinged office. He’s an imposing presence, over six feet tall, with intense dark eyes and a concerningly pale complexion. On his desk sat a cowbell, a pocketknife, a George Orwell reader and an antique ice-cream scoop. There was also a stack of business cards that read: “John A. White III, D.D.S. — Accidentist and Occidental Archaeologist.” “The label is a McGuffin. It’s just a tool to propel us into the next zone. There aren’t that many things left that haven’t already been done, especially with music. I’m interested in ideas that can shake us all up.”

White walked back to a room called the Vault, which is maintained at a constant 64 degrees. He pressed his thumb to a biometric scanner. The lock clicked, and he swung the door open to reveal floor-to-ceiling shelves containing the master recordings of nearly every song he’s ever been involved with. Unusually for a musician, White has maintained control of his own masters, granting him extraordinary artistic freedom as well as truckloads of money. “It’s good to finally have them in a nice sealed environment,” White said. I asked where they’d been before, and he laughed. “In a closet in my house. Ready to be set on fire.”

White said the building used to be a candy factory, but I had my doubts. He’s notoriously bendy with the truth — most famously his claim that his White Stripes bandmate, Meg White, was his sister, when in fact she was his wife. Considering the White Stripes named themselves for peppermint candies, the whole thing seemed a little neat. “That’s what they told me,” he insisted, not quite convincingly. I asked if I needed to worry about him embellishing details like that, and he cackled in delight. “Yes,” he said. “Yes.”