Read more.Brain scans show how meditation calms pain

(June 10, 2010)

People who routinely practice meditation may be better able to deal with pain because their brains are less focused on anticipating pain, a new British study suggests.

The finding is a potential boon to the estimated 40 percent of people who are unable to adequately manage their chronic pain. It is based on an analysis involving people who practice a variety of meditation formats, and experience with meditation as a whole ranged from just a few months to several decades.

Only those individuals who had engaged in a long-term commitment to meditation were found to have gained an advantage with respect to pain relative to non-meditators.

“Meditation is becoming increasingly popular as a way to treat chronic illness such as the pain caused by arthritis,” study author Dr. Christopher Brown, from the University of Manchester’s School of Translational Medicine, said in a university news release.

Offering multiple perspectives from many fields of human inquiry that may move all of us toward a more integrated understanding of who we are as conscious beings.

Saturday, June 12, 2010

Wildmind Buddhist Meditation - Brain scans show how meditation calms pain

Steven Pinker - Mind Over Mass Media

Mind Over Mass Media By STEVEN PINKER

Published: June 10, 2010

Truro, Mass.NEW forms of media have always caused moral panics: the printing press, newspapers, paperbacks and television were all once denounced as threats to their consumers’ brainpower and moral fiber.

So too with electronic technologies. PowerPoint, we’re told, is reducing discourse to bullet points. Search engines lower our intelligence, encouraging us to skim on the surface of knowledge rather than dive to its depths. Twitter is shrinking our attention spans.

But such panics often fail basic reality checks. When comic books were accused of turning juveniles into delinquents in the 1950s, crime was falling to record lows, just as the denunciations of video games in the 1990s coincided with the great American crime decline. The decades of television, transistor radios and rock videos were also decades in which I.Q. scores rose continuously.

For a reality check today, take the state of science, which demands high levels of brainwork and is measured by clear benchmarks of discovery. These days scientists are never far from their e-mail, rarely touch paper and cannot lecture without PowerPoint. If electronic media were hazardous to intelligence, the quality of science would be plummeting. Yet discoveries are multiplying like fruit flies, and progress is dizzying. Other activities in the life of the mind, like philosophy, history and cultural criticism, are likewise flourishing, as anyone who has lost a morning of work to the Web site Arts & Letters Daily can attest.

Critics of new media sometimes use science itself to press their case, citing research that shows how “experience can change the brain.” But cognitive neuroscientists roll their eyes at such talk. Yes, every time we learn a fact or skill the wiring of the brain changes; it’s not as if the information is stored in the pancreas. But the existence of neural plasticity does not mean the brain is a blob of clay pounded into shape by experience.

Experience does not revamp the basic information-processing capacities of the brain. Speed-reading programs have long claimed to do just that, but the verdict was rendered by Woody Allen after he read “War and Peace” in one sitting: “It was about Russia.” Genuine multitasking, too, has been exposed as a myth, not just by laboratory studies but by the familiar sight of an S.U.V. undulating between lanes as the driver cuts deals on his cellphone.

Moreover, as the psychologists Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons show in their new book “The Invisible Gorilla: And Other Ways Our Intuitions Deceive Us,” the effects of experience are highly specific to the experiences themselves. If you train people to do one thing (recognize shapes, solve math puzzles, find hidden words), they get better at doing that thing, but almost nothing else. Music doesn’t make you better at math, conjugating Latin doesn’t make you more logical, brain-training games don’t make you smarter. Accomplished people don’t bulk up their brains with intellectual calisthenics; they immerse themselves in their fields. Novelists read lots of novels, scientists read lots of science.

The effects of consuming electronic media are also likely to be far more limited than the panic implies. Media critics write as if the brain takes on the qualities of whatever it consumes, the informational equivalent of “you are what you eat.” As with primitive peoples who believe that eating fierce animals will make them fierce, they assume that watching quick cuts in rock videos turns your mental life into quick cuts or that reading bullet points and Twitter postings turns your thoughts into bullet points and Twitter postings.

Yes, the constant arrival of information packets can be distracting or addictive, especially to people with attention deficit disorder. But distraction is not a new phenomenon. The solution is not to bemoan technology but to develop strategies of self-control, as we do with every other temptation in life. Turn off e-mail or Twitter when you work, put away your Blackberry at dinner time, ask your spouse to call you to bed at a designated hour.

And to encourage intellectual depth, don’t rail at PowerPoint or Google. It’s not as if habits of deep reflection, thorough research and rigorous reasoning ever came naturally to people. They must be acquired in special institutions, which we call universities, and maintained with constant upkeep, which we call analysis, criticism and debate. They are not granted by propping a heavy encyclopedia on your lap, nor are they taken away by efficient access to information on the Internet.

The new media have caught on for a reason. Knowledge is increasing exponentially; human brainpower and waking hours are not. Fortunately, the Internet and information technologies are helping us manage, search and retrieve our collective intellectual output at different scales, from Twitter and previews to e-books and online encyclopedias. Far from making us stupid, these technologies are the only things that will keep us smart.

~ Steven Pinker, a professor of psychology at Harvard, is the author of “The Stuff of Thought.”

BPS Research Digest - What's this psychopathy hoo-ha all about?

What's this psychopathy hoo-ha all about?

A psychology paper by David Cooke and Jennifer Skeem critical of the dominant tool for measuring psychopathy has finally been published after years lying dormant. The delay, according to reports, was due to threats of libel by lawyers representing Robert Hare, author of the criticised tool.

Curiously, back in 2007, when the contentious paper was first moth-balled, a similar and related paper (free to access), also by Cooke and Skeem, plus statistician Christine Michie, was published in the British Journal of Psychiatry. In fact, this paper describes itself as the 'analytical' companion to the 'logical and theoretical' paper that was buried for so long.

So what did the paper that managed to get published back in 2007 have to say? Echoing the scholarly tussles that have surrounded the measurement of many factors in psychology, such as intelligence and personality, Cooke and his co-authors grapple with how best to provide a concrete measurement of a slippery abstract concept, in this case psychopathy.

The gist of their argument is that psychopathy is most appropriately measured by a three-factor version of Hare's Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R), tapping: arrogant and deceitful interpersonal style; deficient affective experience; and impulsive and irresponsible behavioural style. In short-hand you could say this translates as nasty, unemotional and uninhibited. The point of contention is that Hare's widely used PCL-R measure of psychopathy adds a fourth factor - criminality.

Cooke and his colleagues think this is a big mistake and to support their claims they ran a number of different versions of the psychopathy checklist on answers given by over 1000 adult male offenders. In conclusion, they wrote:'Psychopathy and criminal behaviour are distinct constructs. If we are to understand their relationships and, critically, whether they have a functional relationship, it essential that these constructs are measured separately. This is particularly critical within the context of the Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorders project, where individuals are detained because of the assumption of a functional link between their personality disorder and the risk that they pose.'In other words, a measure that conflates psychopathy and criminality risks confusing any attempts to understand the links between psychopathy and criminal acts such as rape and murder. Moreover, if raping and murdering become part of the definition of psychopathy, then what sense is there of running a risk assessment on a person diagnosed as psychopathic?

Cooke et al are currently developing what they describe as a 'more comprehensive' model of the construct of psychopathy based on 33 symptoms grouped into six domains. Criminality isn't one of them.

_________________________________Cooke, D., Michie, C., & Skeem, J. (2007). Understanding the structure of the Psychopathy Checklist - Revised: An exploration of methodological confusion. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190 (49) DOI: 10.1192/bjp.190.5.s39

Link to Mind Hacks update on the saga of the buried paper (thanks to Mind Hacks for alerting me to this unfolding story).

Link to In the News Forensic Psychology blog, with more updates.

Link to related (paywalled) Science journal news item.

Wiring the Brain - What is a “neurodevelopmental disorder”?

What is a “neurodevelopmental disorder”?

This question arose at the recent, excellent meeting of the International Society for Developmental Neuroscience in Estoril, Portugal. The question came up due to some very exciting and very unexpected successes in reversing in adult animals the effects of mutations causing neurodevelopmental disorders, including neurofibromatosis, Down syndrome, Rett syndrome and tuberous sclerosis.

All of these disorders are caused by specific genetic lesions and characterised by very early deficits, variously including intellectual disability, autism, epilepsy and other psychological and neurological phenotypes. They are also associated with some degree of neuropathology, usually involving differences in the elaboration of neuronal morphology, branching and connectivity. Because of the early onset of symptoms, these disorders have traditionally been considered as being due to defects in neurodevelopment that have led to a permanently structurally compromised brain. The last thing most people would have expected is that many of the cognitive deficits in these disorders would be reversible in adults, by either restoring normal gene function or by compensating for the effects of the genetic lesion.

Article reference:

EHNINGER, D., LI, W., FOX, K., STRYKER, M., & SILVA, A. (2008). Reversing Neurodevelopmental Disorders in Adults Neuron, 60 (6), 950-960 DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.007

Friday, June 11, 2010

Pavel Somov, Ph.D. - Perfection: Aristotle versus Buddha

Cool . . . . From Huffington Post.

Perfection: Aristotle versus Buddha

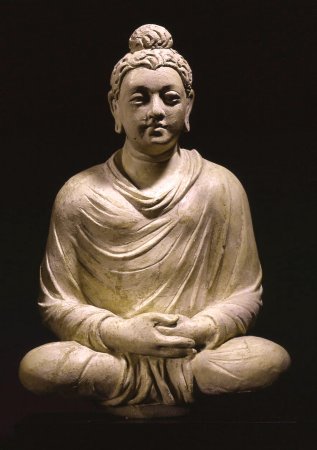

By Pavel Somov, Ph.D."The Buddha lived in India five centuries before Jesus and almost two centuries before Aristotle. The first step in his belief system was to break through the black-and-white world of words, pierce the bivalent veil and see the world as it is, see it filled with 'contradictions,' with things and not-things, with roses that are both red and not-red, with A and not-A. You find this [...] theme in Eastern belief systems old and new, from Lao-tze's Taoism to the modern Zen in Japan. Either-or versus contradiction. A or not-A versus A and not-A. Aristotle versus the Buddha." (B. Kosko)

Seeing yourself as either perfect or imperfect is black-and-white thinking. Time to update your understanding of perfection from the standard Western, psychologically toxic, dualistic view of perfection to a more self-accepting, psychologically healthier, nondual view of perfection: you are neither perfect nor imperfect or, if you prefer, you are perfectly imperfect. Same thingless thing!

Perfectionism suffers from Aristotelian dichotomies and bivalences: it cuts life in half, into "what is" and "what should be," into "perfect" and "imperfect," into "actual" and "ideal." A perfectionistic mind is sore with the either/or self-fragmentation. Time to learn to accept your whole self in its existential continuity. In other words, time to stop falling onto this Aristotelian sword of black-and-white self-judgment.

Yes, you are doing the best that you can at any given point in time and you can still do better. Time to perfect perfection!

Resources:

Pavel Somov, Ph.D. is the author of:Douglas LaBier - Building An Inside-Out Life - Part 1

Interesting post from Douglas LaBier's The New Resilience blog at Psychology Today. Learning to balance our inner and outer lives seems to be part of the key to resilience.

Building An Inside-Out Life - Part 1

The true balance is between your inner and outer lifePublished on June 8, 2010The Myth of Work-Life Balance

Meet Linda and Jim, who consulted me for psychotherapy. Linda is a lawyer with a large firm; Jim heads a major trade association. They told me they're totally committed to their marriage and to being good parents. But they also said it's pretty hectic juggling all their responsibilities at work and at home They have two children of their own plus a child from her former marriage. Dealing with the logistics of daily life, to say nothing of the emotional challenges, makes it "hard just to come up for air," Linda said. Sound familiar?

Or listen to Bill, a 43-year-old who initially consulted me for help with some career challenges. Before long, he acknowledged that he's worried about the "other side" of life. He's raising two teenage daughters and a younger son by himself - one of the rising numbers of single fathers. He's constantly worried about things like whether a late meeting might keep him at work. He tries to have some time for himself, but "it's hard enough just staying in good physical health, let alone being able to have more of a ‘life,' " he said. Recently, he learned he has hypertension.

It's no surprise that these people, like many I see in my psychotherapy practice as well as in my workplace consulting, feel pummeled by stresses in their work and home lives. Most are at least dimly aware that this is unhealthy - that stress damages the body, mind and spirit. Ten years ago, a report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, found that 70 percent of all illness, physical and mental, is linked to stress of some kind. And that number has probably increased over the last decade. Much of this stress comes from struggling with the pressures of work and home - and trying to "balance" both. The problem seems nearly universal, whether in two-worker, single-parent or childless households.

I think these conflicts are so common because people have learned to frame the problem incorrectly to begin with. That is, there's no way to balance work life and home life, because both exist on the same side of the scale - what I call your "outer" life. On the other side of the scale is your personal, private life - your "inner" life. Instead of thinking about how to balance work life and home life, try, instead, to balance your outer life and inner life.

A Different Balancing Act

Let me explain. On the outer side of the scale you have the complex logistics and daily stresses of life at both work and home - the e-mails to respond to, the errands, family obligations, phone calls, to-do lists and responsibilities that fill your days. Your outer life is the realm of the external, material world. It's where you use your energies to deal with tangible, often essential things. Paying your bills, building a career, dealing with people, raising kids, doing household chores, and so on. Your outer life is on your iPhone, BlackBerry, or your e-calender.On the other side of the scale is your internal self. It's the realm of your private thoughts and values. Your emotions, fantasies, spiritual or religious practices. Your capacity to love, your secret desires, and your deeper sense of purpose. In short, it embodies who you are, on the inside. A "successful" inner life is defined by how well you deal with your emotions, your degree of self-awareness , and your sense of clarity about your values and life purpose. It includes your level of mental repose: your capacity for calm, focused action and resiliency that you need in the face of your frenetic, multitasking outer life.

If the realm of the inner life sounds unfamiliar or uncomfortable to you, this only emphasizes how much you - like most people - have lost touch with your inner self. You can become so depleted and stretched by dealing with your outer life that there's little time to tend to your mind, spirit or body. Then, you identify your "self" mostly with who you are in that outer realm. And when there's little on the inner side of the scale, the outer part weighs you down. You are unbalanced, unhappy and often sick.

When your inner life is out of balance with your outer, you become more vulnerable to stress, and that's related to a wide range of physical damage. Research shows that heart attacks, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, a weakened immune system, skin disorders, asthma, migraine, musculoskeletal problems - all are linked to stress.

More broadly, when your inner and outer lives become unbalanced, your daily functioning is affected in a range of ways, both subtle and overt. When operating in the outer world - at work, for example, or in dealings with your spouse or partner - you may struggle with unjustified feelings of insecurity and fear. You may find yourself at the mercy of anger or greed whose source you don't understand. You may be plagued with indecisiveness or revert to emotional "default" positions forged during childhood, such as submissiveness, rebellion or self-undermining behavior.

Even when you're successful in parts of your outer life, neglecting the inner remains hazardous to your psychological and physical health. Without a developed inner life, you lose the capacity to regulate, channel and focus your energies with awareness, self-direction and judgment. Personal relationships can suffer, your health may deteriorate and you become vulnerable to looking for new stimulation from the outer-world sources you know best - maybe a new "win," a new lover, drugs or alcohol.

And that pulls you even more off-balance, possibly to the point of no return. The extreme examples are people who destroy their outward success with behavior that reflects a complete disengagement from their inner lives - corporate executives led away in handcuffs for indulging in ill-gotten gains, self-destructive sports stars overcome by the trappings of their outer-life successes, political leaders whose flawed personal lives destroy their credibility, clerics who are staunch moralists at the pulpit but sexual predators or adulterers behind closed doors.

These are our modern-day counterparts of Shakespearian characters like Macbeth or Coriolanus, whose "outer" lives are toppled over by unconscious aims, destructive arrogance or personal corruption.

Of course, most people want to function well in the outer, material world. Doing so is part of a successful adult life. But what you choose to go after in work and life often reflects values and behavior that you've been socially conditioned into through your family and society. Much of that can be hard to see because you're immersed in it. What gets lost along the way is what your inner life might tell you about the consequences and value of what you pursue in your outer life.

Learning To Rebalance

But there's good news: Reframing your challenge from trying to balance work and home to balancing your inner and outer lives will help you build overall health, internal well-being and resilience in your pursuit of outer life success.That is, servicing your inner life builds healthy, positive control over your life - mastery and self-directed action, not suppression or rationalization. A stronger inner life creates a solid moral core and harmonizes your inner and outer selves. It informs your choices and actions by providing the calm and centeredness essential for knowing what demands or allures of the outer world you want to go after, or let pass; and how to deal with the consequences of either.

For example, clarifying which of the personal commitments, career goals and relationships you want or don't want. Whether this job or career is what you really desire, despite the money it pays or what people tell you that you should want. And, whether you believe that your relationship gives you and your partner the kind of positive, energized connection you want and need.

In short, a strengthened inner life brings your "private self" and your "public self" into greater harmony. That's the foundation you need for dealing with the stress-potential of outer world choices and conflicts; for knowing how and why you're living and using your energies out there in the ways that you do. With a robust inner life you feel grounded and anchored. You know who you are and what you're truly living for. Your inner life builds a state of heightened self-awareness and wholeness; a "heart that listens," as King Solomon asked for.Finding The Gaps

Brad was a financial consultant, noticeably underdeveloped in his inner life. One day he came face-to-face with a classic inner-vs.-outer dilemma. For him, that triggered an important awakening. He was debating whether to leave an out-of-town meeting early, which would create some difficulties, in order to be at home for his daughter's 18th birthday.I asked him the simplest question: Which choice would he be more likely to feel good about at the end of his life? Tears came to his eyes as he said that he knew in his heart that it was being at his daughter's birthday. He told me that he felt enormously troubled by the fact that he'd been trying to rationalize away what he knew he valued more deeply.

At that moment Brad was able to see the gap between his inner life values - his true self - and the choice he was about to make based on his outer life conditioning - his false self.

His awakening to his inner-outer gaps is instructive. A good initial step toward awakening your inner life is to identify the gaps between what you believe in, on the inside, and what you do on the outside. Everyone has those gaps. Here's an exercise that can help you awaken to them:

- First, make a list of what you believe to be your core, internal values or ideals (5- 10 entries). Perhaps it includes raising a strong, creative child; close friendships; expressing a creative talent that's important to you. It might include your spiritual life; an intimate marriage or partnership; or contributing your talents, energies or success to the society in some way.

- Next, make a parallel list for each item on your list, describing your daily actions relative to those values: How much time and energy do you spend on them in real time? What are your specific behaviors regarding each? Be detailed in your answers - note the last time you took an action aimed at nurturing that creative child, building your marriage or giving some meaningful help to the less fortunate. Don't be surprised or ashamed if you find that very few of your daily activities reflect those key values.

- Assign a number from 1 to 5 measuring the gap between each value and your behavior - 1 representing a minimal gap; 5, the maximum.

- Identify the largest gaps. Now think about how your inner values could redirect your outer-life choices in those areas. What would you have to do to bring the inner you in synch with the outer you? What can you commit yourself to doing?

- Write it all down and set a reasonable time frame for reducing your gaps.

Developing your inner life is a practice. Think of it like building a muscle or developing skill in a sport or musical instrument.

In Part 2 of this post I'll describe some practices most anyone can do to build a stronger inner life. They involve your mind, body, spirit and actions in daily life. You will see that the more you do, the better, because they reinforce each other. They help you build greater psychological health and resilience in today's unpredictable world.

dlabier@centerprogressive.org

My Blog: Progressive Impact

Web Site: Center for Progressive Development

About Me

©2010 Douglas LaBier

Jürgen Habermas - Between Naturalism and Religion: Philosophical Essays

Jürgen Habermas

Between Naturalism and Religion: Philosophical Essays

Translated by Ciaran Cronin. Polity Press, Cambridge, 2008. 361pp., £18.99 pb

ISBN 9780745638256Reviewed by Paula Cerni

Paula Cerni (MPhil) is an independent writer. For a list of publications, please visit paulacerni.wordpress.com.Review

Guided by his well-known thesis of communicative rationality, Habermas in this book steers a course between scientism and religious intransigence, two polarizing currents, he believes, that are threatening to scupper civic cohesion. But as the Introduction warns, the book’s chapters have been written for different occasions and do not form a systematic whole. Without containing any major theoretical breakthroughs, they leave it to the reader to piece together Habermas’s still-evolving views against a background of contemporary issues, from multiculturalism through to the boundary between faith and knowledge and the development of international law. While the volume will be of interest to all students of social, moral and political philosophy as well as philosophy of religion and philosophy of science, it is best suited to those who are already familiar with the author and wish to see his latest thinking in action.

Readers should also be warned that the book is written in a cumbersome style, with the biographical Chapter 1 a welcome exception. As Habermas tells it, his early life was marked by a cleft palate that forced him to undergo surgery, made it difficult and frustrating to communicate, and led to some humiliation. These experiences awoke in him a sense of the importance of connecting with others and respecting differences, so that ‘the social nature of human beings later became the starting point for my philosophical reflections’ (13).

But as a child Habermas also lived through WWII, and in his youth he witnessed the fall of the Nazi regime in his native Germany and the painful efforts to return the country to a working democracy. Habermas confesses that up to the 1980s he lived in fear of a relapse. The publication in 1953 of Heidegger’s 1935 lectures (An Introduction to Metaphysics) without any editing, and so implicitly without a renunciation of its pro-Nazi views, was a powerful reminder of ‘the oppressive political heritage that persisted even in German philosophy’ (20). And yet the eventual success of post-war Germany seems to have instilled in Habermas some confidence that formal democracy and the intervention of the ‘international community’ can bring about political stability. As a consequence, and in spite of his connections to Marxism via the Frankfurt School, and of his left-leaning activism over the years on issues ranging from nuclear weapons to asylum laws, Habermas’s main concern appears to be that of forging a political consensus above society’s fundamental divisions.

All the same, Habermas’s faith in practical bourgeois democracy sets him apart from the cynical thinking of many of his contemporaries, most notably those ‘critiques that destroy reason through its abstract negation, such as Foucault’s objectivating analysis or Derrida’s use of paradox’ (25). In chapters 2 and 3 he situates his own thought within an alternative tradition, one that includes Hegel and Marx and reclaims reason as pragmatic and historical, as reason ‘in the world’. But over the course of his long career Habermas has come to locate the foundations of this detranscendentalized or postmetaphysical reason in the inter-subjective constitution of the human mind, and to anchor his philosophy less on historical materialism than, among other influences, on the hermeneutic or interpretative tradition initiated by Wilhelm von Humboldt, on American pragmatism, on analytic philosophy of language, and on Kant.

The result is a formal and universalist pragmatics that hinges on the concept of discourse, the procedure by which arguments are subject to public testing. Rational discourse, argues Habermas, ‘presents itself as the appropriate procedure for resolving conflicts because it ensures the inclusion of all those affected and the equal consideration of all the interests concerned’ (48). But, of course, equal consideration does not equalize the divided interests out of which conflicts arise in the first place. Habermas is aware of this, yet places little hope on the ‘strategic rationality’ that would be required to overcome social divisions. He seems to believe that the formal features of argumentation are the only commonality left to ‘the sons and daughters of “homeless” modernity’ (87), but surely this cannot be correct, because even in our modern times conflict usually occurs within and between communities of interest – in societies made up of mutually dependent individuals, between social classes, etc. Humanity is not as homeless as Habermas assumes, and if it was argumentation would be quite pointless.

The Habermasian emphasis on communication is part of the broader turn from epistemology to language characteristic of twentieth-century philosophy, a turn that highlighted an important aspect of human agency, but, since language by itself is not emancipative, any more than knowledge by itself is, did not represent a significant advance for philosophy. Habermas senses that communication cannot carry the full burden of social consensus, and so, in Chapter 4, as part of a discussion with then Cardinal Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI) he takes up the question whether constitutional democracy relies on pre-political forces such as religion. No, he answers, because ‘legitimacy is generated from legality’ (104), but nevertheless it is ‘in the interest of the constitutional state to conserve all cultural sources that nurture citizens’ solidarity and their normative awareness’ (111). That organized religion might also be damaging to human relations – as illustrated by the child-abuse scandal now rocking the Catholic Church and even the Pope himself – is not an argument that figures in this book. Implicit in its so-called ‘postsecular’ understanding of the role of religion in modern society is a bargain whereby religion is recognized by the state in exchange for its contribution to maintaining social order and motivating believers to participate in political life. Against Habermas’s own formal pragmatics, this bargain represents an admission that modern politics ultimately depends on the interest-driven participation of civil society.

Habermas’s concern with the terms of such participation leads him to engage, in Chapter 5, with the important debate about religious expression in a democratic polity. Treading a careful line between John Rawls and his critics, he concludes that the state must justify its political positions in a secular language, but cannot demand individual citizens do the same. It’s a sensible conclusion, though the need for a secular state does not follow, as Habermas believes, from the Rawlsian ‘fact of pluralism’, but from the very character of democracy as rule according to the will of the people instead of the will of God. As such it would apply also in conditions of religious homogeneity.

In the next two chapters Habermas responds to the renewed controversy over freedom and determination that has resulted from recent advances in the natural sciences, particularly genetics and neurobiology. Wanting to challenge the anti-mentalist slant of modern science, he reclaims Wilfrid Sellars’ ‘space of reasons’. For Habermas this space is above all cultural and inter-subjective, so that freedom of action belongs ‘to the dimension of objective mind’ (173), that is to say, to ‘mind as symbolically embodied in signs, practices and objects’ (174), rather than to our capacity to join causes with reasons by shaping the objective world according to our subjective purposes.

In the absence of a dialectical materialist concept of freedom and of the projects of large-scale social transformation that could follow from it, Habermas in Chapter 8 turns to Kant’s philosophy of religion to argue for a secular appropriation of the semantic content of religious traditions. More accurately, however, such appropriation is really a re-appropriation, since, in order to be translatable into secular terms, religious contents must be, in Habermas’s own formulation, ‘profane truths’ in the first place – that is to say, secular contents in disguise.

But Habermas’s wish to save such contents contradicts his own rejection of a rationalist critique of religion in favor of a ‘dialogical’ approach that does not presume to ‘decide what is true or false in religion’ (245). For how can we identify any profane truths in religion to begin with? This is a question Habermas does not ask, though he evidently has his own method for amending Kant’s translation of the idea of the kingdom of God into a universal ethical community. The universalism that Habermas wants is not to be realized in a future society where human beings no longer use and exploit each other, but in the current political procedures whereby citizens and groups negotiate their cultural identities. Hence he argues, against Kant, that ‘we must first affirm that conceptions of the kingdom of God and of an “ethical community” are inherently plural’ (239). But pluralism is only a necessary democratic means to create and sustain a public sphere in the face of social and religious conflict; it is far less ambitious than the abolition of such conflict envisioned by Kant, Marx, and many religious doctrines.

Chapters 9 and 10 deal with the politics of tolerance. While Habermas argues for sensitivity to cultural differences, he places strict limits on political tolerance. A democratic state such as Germany’s ‘must resort to intolerance toward enemies of the constitution, either by employing the mechanisms of political criminal law or by prohibiting particular political parties (Article 21.2 of the German Basic Law) and suspending basic rights (Article 18 and Article 9.2 of the same)’ (255). The enemies he has in mind include ‘the political ideologist who combats the liberal state’ as well as ‘the fundamentalist who violently attacks the modern way of life as such’ (255). Habermas does see the threat of authoritarianism here, reminding us that those ‘who are suspected of being “enemies of the state” may very well turn out to be radical defenders of democracy’ (255). But exploring the contradictions between the modern state and democracy would require him to investigate the class foundations of that state, which is precisely what his proceduralist approach does not do. Clearly, his illiberal attitude towards the enemies of liberal democracy is informed by the experience of a Nazi regime that came to power with the backing of the masses, but surely that same experience shows also the dangers of intolerant regimes.

In the closing chapter Habermas asserts his support for Kantian cosmopolitanism, but simultaneously dismisses as utopian Kant’s dream of a world republic. Instead, he puts forward proposals that include UN reform as a mechanism to build a more solid supranational structure of constitution-like norms; the formation of strong regional and continental alliances; and a continuation of the system of nations, with the monopoly on force being retained by each state. Altogether, these proposals are fraught with dangers and contradictions that Habermas does not begin to perceive, partly because, at the time of writing, his analysis was still dominated by the concern with neo-liberalism that prevailed on the left before the present economic downturn. If short-term events have already rendered this final chapter out of date, from a longer-term perspective its dramatic scaling-down of Kantian cosmopolitanism illustrates as well as anything else in this book how spent the once-revolutionary spirit of bourgeois philosophy has become. Which of course is no reflection on the personal and intellectual character of its author, but on the times we are all living through.

24 May 2010

Review information

Source: Marx and Philosophy Review of Books. Accessed 9 June 2010

Robert Lanza, M.D. - What Happens When You Die? Evidence Suggests Time Simply Reboots

I'm not a fan of biocentrism - the rather anthropocentric view that life creates the universe rather than the other way around. Robert Lanza's model asserts that "current theories of the physical world do not work, and can never be made to work, until they fully account for life and consciousness."

These are Lanza's seven principle of biocentrism:

- What we perceive as reality is a process that involves our consciousness. An "external" reality, if it existed, would by definition have to exist in space. But this is meaningless, because space and time are not absolute realities but rather tools of the human and animal mind.

- Our external and internal perceptions are inextricably intertwined. They are different sides of the same coin and cannot be divorced from one another.

- The behavior of subatomic particles, indeed all particles and objects, is inextricably linked to the presence of an observer. Without the presence of a conscious observer, they at best exist in an undetermined state of probability waves.

- Without consciousness, "matter" dwells in an undetermined state of probability. Any universe that could have preceded consciousness only existed in a probability state.

- The structure of the universe is explainable only through biocentrism. The universe is fine-tuned for life, which makes perfect sense as life creates the universe, not the other way around. The "universe" is simply the complete spatio-temporal logic of the self.

- Time does not have a real existence outside of animal-sense perception. It is the process by which we perceive changes in the universe.

- Space, like time, is not an object or a thing. Space is another form of our animal understanding and does not have an independent reality. We carry space and time around with us like turtles with shells. Thus, there is no absolute self-existing matrix in which physical events occur independent of life.

Lanza is co-author, with Bob Berman, of Biocentrism: How Life and Consciousness are the Keys to Understanding the True Nature of the Universe. This is his most recent article from Huffington Post. There is no actual evidence in this article, despite title - but don't let that bother you, it doesn't seem to bother Lanza.

What Happens When You Die? Evidence Suggests Time Simply Reboots

Robert Lanza, M.D. - Scientist, TheoreticianPosted: June 10, 2010What happens when we die? Do we rot into the ground, or do we go to heaven (or hell, if we've been bad)? Experiments suggest the answer is simpler than anyone thought. Without the glue of consciousness, time essentially reboots.

The mystery of life and death can't be examined by visiting the Galapagos or looking through a microscope. It lies deeper. It involves our very selves. We wake and find ourselves in the present. There are stairs below us, which we seem to have climbed; there are stairs above us, which go upward into the unknown future. But the mind stands at the door by which we entered and gives us the memories by which we go about our day. Everything is ordered and predictable. We're like cuckoo birds who appear through a door each morning. We fancy there's a clockwork set in motion at the beginning of time.

But if you remove everything from space, what's left? Nothing. The same applies for time -- you can't put it in a jar. You can't see through the bone surrounding your brain (everything you experience is information in your mind). Biocentrism tells us space and time aren't objects -- they're the mind's tools for putting everything together.

I was a young boy when I realized there was something unexplainable about life that I simply didn't understand. I learned this from one of the last smiths in New England, when I, as a child, tried to capture a woodchuck on his property.

Over his shop a chimney cap went round and round, squeak, squeak, rattle, rattle. One day the blacksmith came out with his shotgun and blew it off. The noise stopped. Mr. O'Donnell pounded metal on his anvil all day. No, I thought, I didn't want to be caught by him. Yet, I had my purpose.

The woodchuck's hole was in such close proximity to Mr. O'Donnell's shop that I could hear the bellows fanning his forge. I crawled noiselessly through the long grass, occasionally stirring a grasshopper or a butterfly. After setting a new steel trap that I had just purchased at the hardware store, I took a stake and, rock in hand, pounded it into the ground. When I looked up, I saw Mr. O'Donnell standing there, his eyes glaring. I said nothing, trying to restrain myself from crying. "Give me that trap, child," he said, "and come with me."

I followed him into his shop, which was crammed with all manner of tools and chimes of different shapes and sounds hanging from the ceiling. Starting the forge, Mr. O'Donnell tossed the trap over the coals and a tiny flame appeared underneath, getting hotter until, with a puff it burst into flame. "This thing can injure dogs, and even children!" he said, poking the coals with a fork. When the trap was red hot, he took it from the forge, and pounded it into a little square with his hammer. He said nothing while the metal cooled. At length, he patted me upon the shoulder, and then took up a few sketches of a dragonfly. "I tell you what," he said. "I'll give you 50 cents for every dragonfly you catch." I said that would be fun, and when I parted I was so excited I forgot about my new trap.

The next day I set off with a butterfly net. The air was full of insects, the flowers with bees and butterflies. But I didn't see any dragonflies. As I floated through the last of the meadows, the spikes of a cattail attracted my attention. A huge dragonfly was humming round and round, and when at last I caught it, I hopped and skipped all the way back to Mr. O'Donnell's shop. Taking a magnifying glass, he held the jar up to the light and made a careful study of the dragonfly. He fished out a number of rods, and with a little pounding, wrought a splendorous figurine that was the perfect image of the dragonfly. It had about it a beauty as airy as the delicate insect.

As long as I live I will remember that day. And though Mr. O'Donnell is gone now, there still remains in his shop that little iron dragonfly −- covered with dust now −- to remind me there's something more elusive to life than the succession of shapes we see frozen into matter.

Before he died, Einstein said "Now Besso [an old friend] has departed from this strange world a little ahead of me. That means nothing. People like us ... know that the distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion." In fact, it was Einstein's theory of relativity that showed that space and time are indeed relative to the observer. Quantum theory ended the classical view that particles exist if we don't perceive them. But if the world is observer-created, we shouldn't be surprised that it's destroyed with each of us. Nor should we be surprised that space and time vanish, and with them all Newtonian conceptions of order and prediction.

It's here at last, where we approach the imagined border of ourselves, the wooded boundary where in the old fairy tale the fox and the hare say goodnight to each other. At death, we all know, consciousness is gone, and so too the continuity in the connection of times and places. Where then, do we find ourselves? On stairs that can be intercalated anywhere, like those that Hermes won with the dice of the moon, that Osiris might be born. We think that the past is past and the future the future. But as Einstein realized, this simply isn't the case.

Without consciousness, space and time are nothing; in reality you can take any time -- whether past or future -− as your new frame of reference. Death is a reboot that leads to all potentialities. That's the reality that the experiments mandate. And when I see Mr. O'Donnell's old shop, I know that somewhere the chimney cap is still going round and round, squeak, squeak. But it probably won't rattle for long.

"Biocentrism" (BenBella Books) lays out Lanza's theory of everything.

Thursday, June 10, 2010

Oprah Talks to Geneen Roth about Women, Food, and God

One of my classmates and one of my clients highly recommended Geneen Roth's new book, Women, Food, and God: An Unexpected Path to Almost Everything, so I bought it, but I haven't had a chance to read it yet. I was also aware that Roth had been on Oprah, but I didn't see that either.

So now Oprah is featuring Roth (again) in her magazine, which is available online.

Here is are a couple of brief excerpt from the book and some info about Roth, including her food and eating guidelines.

Why Are You Eating?

The Oprah Winfrey Show | May 12, 2010

Over the years, Oprah has been very open about her struggles with weight. "You all know my story—the highs and lows and ups and downs. My skinny self, my fat self," Oprah says. But after all these years, Oprah says she's finally found the answer. "I have come across something so profound that I think [to everybody] who's ever felt that it's a losing battle, here is an opportunity to win. This has literally broken me open when it comes to my relationship with food, because if you struggle with your weight, what we're about to share with you today might be actually the first time in your life that you begin to understand the real reasons you are fat and allow those reasons to be a miracle for your life."

The discovery in question is author Geneen Roth's new best-selling book, Women, Food, and God. Readers say it's helping to free them from the vicious cycle of yo-yo dieting by getting to the core of why they're overweight.

Geneen says she was a crash dieter herself for many years, gaining and losing more than 1,000 pounds, but after finding herself on the brink of suicide, she had a breakthrough. "First of all, not dieting. Dieting leads to self-hatred and self-loathing, making you feel crazy about yourself," she says. "The other breakthrough is that your relationship with food, rather than being the curse, and rather than being the thing that you want to get rid of, is, itself, the doorway to the life you most want."

Having issues with weight is always about more than the food, Geneen says. "Your beliefs show up in your relationship with food. So if I'm eating when I'm not hungry or bored, I'm basically saying I can't feel these feelings. 'Life is too much for me. There's no goodness in my life except for food right here, right now,'" she says. "You're basically eating because you've given up on something, some part of yourself."

Oprah says she had an aha! moment when reading about how people's relationships with food mirrors their belief systems. "I realized that is what I have done, and so many other people have done, for years. You think that, 'I am so small that the pain is going to overwhelm me,' but really the truth is you've already experienced that pain," she says.

"Yes, you have, and what food does at that point is it doubles your pain, rather than make it go away," Geneen says. "You're still in pain about what you were in pain about before you ate, but now you've added a whole level of more discomfort which is: 'Oh, I can't believe I ate this. What's wrong with me? Am I ever going to get my life together? Is it ever going to get better?' Then you're feeling like a failure on top of the discomfort you were feeling before."

Lots of people understand why women and food are mentioned in the title of Geneen's book, but why God? Geneen says she isn't talking about God in the religious sense. Instead, she's talking about what she calls the source. "We each have this longing—we've had moments of awe and wonder in our lives. A lot of us don't call that God, but we know that something is possible for every one of us besides our daily lives, the daily grind. The way we get caught with errands and emails and taking care of other people. We feel that this possibility exists," Geneen says. "I'm talking about wonder and mystery and possibility ... or the feeling you have in nature. The feeling that everything is possible."

Oprah says that in reading Women, Food, and God, she has learned that a woman's relationship with food is directly related to how close she is to the source. "That's really what this book is about," she says. "The issue isn't really the food. It is about your disconnection from that which is real which we call God."

In Women, Food, and God, Geneen delves into why women turn to food even when they aren't hungry. "Obsession gives you something to do besides have your heart shattered by heart-shattering events," she writes.

The emotional struggle that accompanies overeating is familiar, Geneen says, whereas the "heart-shattering events" are often new and raw. "People are afraid that the pain will destroy them. Or the heartbreak, or the discomfort even. ... We don't actually know that we can feel those feelings without being destroyed by them," she says. "Getting up and living day-to-day and going through the stuff of day-to-day, that's difficult. But somehow we believe that food is cushioning it."

Oprah says even she turns to food when life gets hard. "There's still anxiety when I have to say no to someone," she says. "I still worry, 'What are they going to think' ... [That happened to me recently and] I did not eat a pound of potato chips. I ate a pound of lettuce. But it's the same thing. I've switched the drug from potato chips to lettuce."

In that moment, Oprah says she started questioning her actions. After saying no and standing up for herself, why was she so anxiety-ridden that she had to eat a bowl of lettuce? "I went back to what you had said in the book,” she says. “What I'm really feeling is every time I have ever been beaten by my grandmother. ... What I recognize as I'm stuffing myself with the lettuce is I still have that feeling of if I don't do what pleased the other person, then somehow that person has the power to annihilate me."

Conquering issues with weight starts with learning to love yourself, Geneen says. "People say, 'I hate myself and I hate my thighs and how do I start looking at myself and loving myself?' And sometimes I'll say: 'How would you treat a child who needed your love? Would you just whack them around and just say: 'Wrong! Bad. Look at your thighs, look at your legs'? No. Kindness. Only kindness makes sense. Only kindness ever makes sense."

It's especially important to treat ourselves as we would our children, because our children mirror our actions, Geneen says. One audience member says she's terrified that she's passing on her own food issues to her child. "My daughter, who just turned 7 yesterday, she said, 'I want you to take me home so I can change my clothes before school because my thighs are too big,' and she's the tiniest little thing. It kills me that I've taught her in seven short years to hate herself," she says.

Geneen says this mother's attitude toward herself is rubbing off on her daughter. "She sees her mom not liking herself and she's thinking: 'I love my mommy. I want to be just like my mommy. I'm not going to like myself either, that way mommy and I are the same,'" Geneen says. "That's a really good motivation for you to start being kinder to yourself, because ... it's not too late. It's never too late."

Geneen has helped countless women conquer their battle with weight. Jennifer, who has struggled with being both over and underweight, says she hasn't fluctuated in weight or dieted since attending one of Geneen's seminars. "What mostly clicked was recognizing that going to the food wasn't working and that what I was looking for wasn't in the food. So what I was trying to get rid of and what I was trying to not feel, it didn't help to be eating over it," Jennifer says. "The other thing that clicked was that there was a whole lot of pain there to look at. I needed to look at some of the layers, recognizing some of the beliefs that were keeping me at the weight where I was." Those beliefs, Jennifer says, were that she wasn't good enough, that nobody liked her and that nobody would accept her the way she was.

Jennifer's beliefs are similar to so many women's. "We somehow believe that if we hate ourselves enough, if we shame ourselves enough, we'll end up thin, happy, peaceful people," she says. "Somehow if I torture myself enough, I'll end up feeling great about myself and about my life, as if hatred leads to love and torture leads to contentment."

One common problem women have with weight is the feeling that once they hit a certain number, their entire life will improve. Alexandria says this was her struggle before Geneen helped her conquer her food issues for good. "I lost that notion of dieting and counting calories to really questioning and looking at my believes about my life," she says. "I trust that the hunger that I have, that I can feel my feelings and be with them separately and I can nourish my body with what it wants and trust it."

Today, Alexandria says it feels as if someone turned up the volume on her life. "This work really helped me kind of click some of the pieces of the puzzle into place, and it was about a year ago when I first started doing this work with Geneen—that's when it really accelerated using this as a doorway into my deeper self," she says. “I know I don't have to be finished with this work. I'm not a project to be constantly fixed and worked on. I'm whole right now as I am and everything we have, we need, is right in front of us at this moment. “

To jump-start the change in your life, Geneen says there are seven principles that should guide you. However, Geneen warns against turning these into a diet. "I call them eating guidelines, but I also call them the 'if love speaks' instructions. Because people make them into rules right away, then they have to rebel against them and break them," she says. "So don't make them into a diet."

And here is a little more:In an excerpt from Women, Food, and God, Geneen Roth shares seven guidelines to eating more consciously.Have a question for Geneen about your food and dieting obsessions? Ask her now!

- Eat when you are hungry.

- Eat sitting down in a calm environment. This does not include the car.

- Eat without distractions. Distractions include radio, television, newspapers, books, intense or anxiety-producing conversations or music.

- Eat what your body wants.

- Eat until you are satisfied.

- Eat (with the intention of being) in full view of others.

- Eat with enjoyment, gusto and pleasure.

Geneen Roth's books were among the first to link compulsive eating and perpetual dieting with deeply personal and spiritual issues that go far beyond food, weight and body image. She believes that we eat the way we live and that our relationships to food, money and love are exact reflections of our deeply held beliefs about ourselves and the amount of joy, abundance, pain and scarcity we believe we have (or are allowed) to have in our lives.

Roth has appeared on many national television shows, including The Oprah Winfrey Show, 20/20, The NBC Nightly News, The View and Good Morning America. Articles about Roth and her work have appeared in numerous publications, including O, The Oprah Magazine, Cosmopolitan, Time, Elle, The New York Times, The Chicago Tribune and The Philadelphia Inquirer. She has written a monthly column in Good Housekeeping magazine since 2007. Roth is the author of eight books, including The New York Times best-seller When Food Is Love and a memoir about love and loss, The Craggy Hole in My Heart. Women, Food, and God: An Unexpected Path to Almost Everything is her newest book.

For more information, visit www.GeneenRoth.com.

Explore More from Women, Food, and God:

Are you a permitter or a restrictor? Take the quiz!

What are you hungry for? Hint: It's not food

Read another excerpt from the book

Read more.

What are you hungry for? Hint: It's not food. In fact, it's everything but food. This provocative new book reveals the self-defeating truth about dieting, while lighting the path to a full and healthy life. Says Oprah, "This book is an opportunity to finally end the war with weight and unlock the door to freedom." Below, O's exclusive excerpt.

When I was in high school, I used to dream about having Melissa Morris's legs, Toni Oliver's eyes, and Amy Breyer's hair. I liked my skin, my breasts, and my lips, but everything else had to go. Then, in my 20s, I dreamed about slicing off pieces of my thighs and arms the way you carve a turkey, certain that if I could cut away what was wrong, only the good parts—the pretty parts, the thin parts—would be left. I believed there was an end goal, a place at which I would arrive and forevermore be at peace. And since I also believed that the way to get there was by judging and shaming and hating myself, I also believed in diets.

Diets are based on the unspoken fear that you are a madwoman, a food terrorist, a lunatic. The promise of a diet is not only that you will have a different body; it is that in having a different body, you will have a different life. If you hate yourself enough, you will love yourself. If you torture yourself enough, you will become a peaceful, relaxed human being.

Although the very notion that hatred leads to love and that torture leads to relaxation is absolutely insane, we hypnotize ourselves into believing that the end justifies the means. We treat ourselves and the rest of the world as if deprivation, punishment, and shame lead to change. We treat our bodies as if they are the enemy and the only acceptable outcome is annihilation. Our deeply ingrained belief is that hatred and torture work. And although I've never met anyone—not one person—for whom warring with their bodies led to long-lasting change, we continue to believe that with a little more self-disgust, we'll prevail.

But the truth is that kindness, not hatred, is the answer. The shape of your body obeys the shape of your beliefs about love, value, and possibility. To change your body, you must first understand that which is shaping it. Not fight it. Not force it. Not deprive it. Not shame it. Not do anything but accept and—yes, Virginia—understand it. Because if you force and deprive and shame yourself into being thin, you end up a deprived, shamed, fearful person who will also be thin for ten minutes. When you abuse yourself (by taunting or threatening yourself), you become a bruised human being no matter how much you weigh. When you demonize yourself, when you pit one part of you against another—your ironclad will against your bottomless hunger—you end up feeling split and crazed and afraid that the part you locked away will, when you are least prepared, take over and ruin your life. Losing weight on any program in which you tell yourself that left to your real impulses you would devour the universe is like building a skyscraper on sand: Without a foundation, the new structure collapses.

Change, if it is to be long-lasting, must occur on the unseen levels first. With understanding, inquiry, openness. With the realization that you eat the way you do for lifesaving reasons. I tell my retreat students that there are always exquisitely good reasons why they turn to food.

Can you imagine how your life would have been different if each time you were feeling sad or angry as a kid, an adult said to you, "Come here, sweetheart, tell me all about it"? If when you were overcome with grief at your best friend's rejection, someone said to you, "Oh, darling, tell me more. Tell me where you feel those feelings. Tell me how your belly feels, your chest. I want to know every little thing. I'm here to listen to you, hold you, be with you."

All any feeling wants is to be welcomed with tenderness. It wants room to unfold. It wants to relax and tell its story. It wants to dissolve like a thousand writhing snakes that with a flick of kindness become harmless strands of rope.

The path from obsession to feelings to presence is not about healing our "wounded children" or feeling every bit of rage or grief we never felt so that we can be successful, thin, and happy. We are not trying to put ourselves together. We are taking who we think we are apart. We feel the feelings not so that we can blame our parents for not saying, "Oh, darling," not so that we can express our anger to everyone we've never confronted, but because unmet feelings obscure our ability to know ourselves. As long as we take ourselves to be the child who was hurt by an unconscious parent, we will never grow up. We will never know who we actually are. We will keep looking for the parent who never showed up and forget to see that the one who is looking is no longer a child.

I tell my retreat students that they need to remember two things: to eat what they want when they're hungry and to feel what they feel when they're not. Inquiry—the feel-what-you-feel part—allows you to relate to your feelings instead of retreat from them.

"Notice whatever arises, even if it surprises you"

Neal M. Goldsmith Ph.D - Psychedelics, Psychotherapy, and Change

Neal Goldsmith, Ph.D. - Psychedelic Therapy and Change: Research, Challenges, Implications

This talk will introduce tracks 2 and 3 for the conference, and so will be part about my research, but very much about the theme and focus of the tracks. I’ll start by describing the tracks, and the history it comes from and contributes to. I’ll then outline the research environment, focus, and results from 1947 to the present, outlining how the climate has changed over the decades, the key research areas (substance abuse, end-of-life, etc.) and findings, and the current research underway and planned. Next, I’d like to focus on key open questions (e.g., Can psychedelics provide lasting cures? Is psychedelic spirituality real; helpful? Should we take a medical, sacramental, or some other approach to this work? Is double blind effective; necessary? How will psychedelic researchers and therapists be trained? What should be done about re-scheduling psychedelics? How can we introduce psychedelics into mainstream medicine; society?) I’d then like to move to a discussion of how medicine, science, and Western culture as a whole will be changed by the re-integration of psychedelics into society. I’d like to close with a review of the Therapy/Cultural track, it’s aims and approaches, outlining the panels in the track and how they will help us address the issues raised in this talk.

Biography: Neal M. Goldsmith, Ph.D. is a psychotherapist and consultant in private practice, specializing in psychospiritual development – seeing “neurosis” as the natural unfolding of human maturation. Dr. Goldsmith’s psychotherapy training includes Imago Relationship Therapy, Psychosynthesis, yoga psychology, regressive psychotherapies, Rogerian client-centered counseling, and other humanistic, transpersonal and eastern traditions (in addition to the lessons found in the research literature on psychedelics). He is also an applied research psychologist and strategic planner working with institutions such as Princeton University, AT&T, American Express, and Gartner to foster innovation and change.

Dr. Goldsmith has a master’s degree in counseling from New York University and a Ph.D. in public affairs psychology from Claremont Graduate University, with an orientation toward action science in the tradition of Kurt Lewin. He conducted his dissertation research, on the factors that facilitate or inhibit the successful utilization of mental health policy research, as a federally-funded doctoral research assistant at Princeton University's Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. During this period, Dr. Goldsmith was also deputy principal investigator of a four-year, nation-wide study of the utilization of mental health policy research.

Dr. Goldsmith is a frequent speaker on spiritual emergence, resistance to change, drug policy reform and the post-modern future of society. Among Dr. Goldsmith’s publications, he is perhaps proudest of “The Ten Lessons of Psychedelic Psychotherapy, Rediscovered” (in the Psychedelic Medicine textbook, Praeger, 2007), his affidavit to the California Superior Court in Santa Cruz on “Rescheduling Psilocybin: A Review of the Clinical Research,” and the frequently-cited, “The Utilization of Policy Research.” He is a founder of several salon discussion groups in New York City and of quality improvement councils at American Express Company and AT&T. While still a graduate student, he was an affiliate of the Center for Policy Research at Columbia University, a founder of the Claremont Center for Applied Social Research, and an invited member of the Network of Consultants on Planned Change at the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Goldsmith may be reached via his Web site, www.nealgoldsmith.com.

Other: This talk is based on my forthcoming book: “Psychedelic Healing: The Promise of Entheogens for Psychotherapy and Spiritual Development" (Inner Traditions, in press).