The Global Workspace Model

This is the fourth part of a multi-part post (originally intended to be two parts) on

Bernard Baars'

Global Workspace Theory and the future evolution of consciousness.

In

Part One, I outlined the basic ideas of GWT, suggesting that it may be the cognitive model that is closest to being integral while still being able explain the actual brain circuitry involved in creating self-awareness, the sense of an individual identity, the development of consciousness through stages, the ability of introspection to revise brain wiring, the presence of multiple states of consciousness, and how relationships and the environment (physical, interpersonal, and temporal) may shape and reshape consciousness.

In

Part Two, I established a foundation for a paper that seeks to explain how our consciousness will evolve in the future -

The Future Evolution of Consciousness by John Stewart (ECCO Working paper, 2006-10, version 1: November 24, 2006). His work assumes some specialized knowledge of cognitive developmental theory, so that post attempted to provide some solid background for the ideas that will come up in the next posts.

In

Part Three, I shared a very recent video of Dr. Baars speaking about Global Workspace Theory -

The Biological Basis of Conscious Experience: Global Workspace Dynamics in the Brain - a talk given at the

Evolution and Function of Consciousness Summer School ("Turing Consciousness 2012") held at the University of Montreal. This post was a bit of a detour in the sequence, but it seemed a useful detour.

Most recently, I took

another detour into attention and consciousness to look at how they are distinct functions with unique brain circuits. Many models incorrectly see the two as so entangled that they must be dealt with as a single entity. This is especially relevant to the GWT model and the evolution of consciousness because attention is a tool to direct consciousness in this explanation of how the brain functions.

* * * * * * *

At the the end of Part Two, we concluded with one of the primary ideas in Stewart's model, the

Declarative Transition, which is the move from Level-I (implicit) procedural knowledge through the E1, E2, and E3 (explicit) phases which constitute the transformation of

implicit procedural knowledge into

explicit declarative knowledge. Once a skill or process reaches the stage of declarative knowledge, it is rarely called into consciousness unless it is targeted directly by some cue, such as a question or in a conversation that requires the piece of information.

We know now, after years of studying these brain functions, that the more often a memory, skill, or piece of knowledge is recalled and rehearsed, the more strongly wired it becomes in the brain. The old cliche is that "practice makes perfect," but the reality is that

practice makes permanent (Robertson, 2009,

From Creation to Consolidation: A Novel Framework for Memory Processing).

When a particular skill or procedure has been revised and expanded using declarative knowledge, it becomes automatic and unconscious again through a process of proceduralization. Stewart summarizes the high-level processing made possible by the proceduralization of declarative memory as unconscious schema:

In any particular domain in which a declarative transition unfolds, the serial process of declarative modelling progressively build a range of new resources and other expert processors, including cognitive skills. Once these processors have been built and proceduralized, they perform their specialist functions without loading consciousness—their outputs alone enter consciousness, without the declarative knowledge that went into their construction. The outputs are known intuitively (i.e. they are not experienced as the result of sequences of thought), and complex situations are understood at a glance (Reber 1989). As noted by Dreyfus and Dreyfus (1987), a person who achieves behavioural mastery in a particular field is able to solve difficult problems just by giving them attention—consciousness recruits the solutions directly from the relevant specialist processors.

In this post, we will look at the process of "evolutionary declarative transitions," as well as additional neuroscientific foundations for the evolution of consciousness.

* * * * * * *

It might be useful to begin with a brief overview of declarative knowledge - it's been a while since I last posted in this series. Declarative memory is what we generally refer to when we think about knowledge - the collection of facts and events that we have access to in memory. Declarative knowledge is also often symbolic knowledge in those who have achieved that level of cognitive development (formal operations in Piaget's model). Timon ten Berge and Rene van Hezewijk (1999,

Procedural and Declarative Knowledge: An Evolutionary Perspective) offer this additional background on declarative memory:

Declarative knowledge can be altered under the influence of new memories. Declarative knowledge is not conscious until it is retrieved by cues such as questions. The retrieval process is not consciously accessible either; an individual can only become aware of the products of this process. It is also a very selective process. A given cue will lead to the retrieval of only a very small amount of potentially available information. Expression of declarative knowledge requires directed attention, as opposed to the expression of skills, which is automatic (Tulving, 1985).

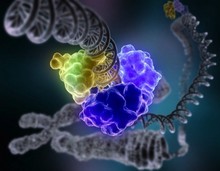

One important difference between implicit/procedural and explicit/declarative knowledge is that declarative knowledge is located in the brain (the medialtemporal region, parts of the diencephalic system and the hippocampus), while procedural memory is less like a "module" and more accurately seen as. well, a procedure or technique, but it does not seem at this point to be localized.

As far as we know, only humans have integrated a declarative transition in their individual development to any great extent. I suspect this is something we will one day (if not already) be able to identify in many other species, including some primates, whales and dolphins, elephants, the higher corvids (crows and ravens), and in some parrots (only a partial list).

At the same time, we have only studied the declarative transition process in individual development and not in our development as a species. There is little doubt that we began as a species functioning through innate genetic responses to the environment. Over time, we moved toward classical and instrumental conditioning, which allowed procedural memory to be acquired through trial and through observational learning. Eventually, procedural knowledge was transformed to declarative knowledge, which could be "

accumulated and transmitted across the generations through the processes of cultural evolution" (Stewart, p. 7).

The problem with the evolution of the human brain is that it followed the laws of selection and adaptation, as evolutionary theory would dictate. So while there are universal adaptations that have become part of our modular mind (Fodor, 1983,

The Modularity of Mind), there is a lot less order and organization to these modules than one might want to see.

Gary Marcus describes this evolutionary process of adaptation as a kluge, a term that originated in the world of computer science and means "a clumsy or inelegant solution to a problem" (Marcus, 2009,

Kluge: Haphazard Construction of the Human Mind). Part of why this is relevant is because it impacts how we learn and how we remember. It's also important because it operates both at the physical level (the mammalian/limbic brain developed on top of the reptilian brain, and the neocortex developed over the limbic brain - as in the image below)

and in the realm of mind, where functions are highly interdependent.

One example of how this plays out is that non-localized procedural memory seems to be an earlier evolutionary trait than the more localized declarative memory (Bloom and Lazerson, 1988,

Brain, Mind, and Behavior), which allows procedural memory to be less impacted by brain injuries or lesions (one might lose verbal skills or autobiographical memory, but still be able tie your shoes or ride a bicycle).

This evolutionary kluge in brain/mind development is likely reflected in declarative transitions during our species' development. Declarative transitions probably occurred at different times, in longer or shorter periods of time, and in different domains (cognitive, spatial, emotional, sexual, and so on). How and when this happened was influenced by climate, food supply, language skills, availability of sexual partners, size of clan or tribal groups, and dozens of other factors impossible to quantify.

In fact, this is a perfect example of a complex "

dynamical system embedded into an environment, with which it mutually interacts" (Gros, 2008,

Complex and Adaptive Dynamical Systems, A Primer). Further:

Simple biological neural networks, e.g. the ones in most worms, just perform stimulus-response tasks. Highly developed mammal brains, on the other side, are not directly driven by external stimuli. Sensory information influences the ongoing, self-sustained neuronal dynamics, but the outcome cannot be predicted from the outside viewpoint.

Indeed, the human brain is by-the-large occupied with itself and continuously active even in the sustained absence of sensory stimuli. A central theme of cognitive system theory is therefore to formulate, test and implement the principles which govern the autonomous dynamics of a cognitive system. (p. 219)

One issue in this realm is the consistent push toward equilibrium. The brain is always trying to balance the incoming sensory data from the environment with the internal cues from the autonomic (sympathetic and parasympathetic) and somatic nervous systems. Processing all of this information and regulating the body requires a lot of energy - the brain (as less than 2% of our total mass) uses about 20% of the calories we burn each day.

But it also means that we can never think about the human brain/mind without also considering its environment - physical, interpersonal, and temporal. We are physically, environmentally, emotionally, and culturally embedded beings. Trying to conceive of human consciousness without taking all of this into account is a recipe for reductionism.

Most of the complex work performed by the brain occurs below the level of conscious awareness, in what Daniel Kahneman calls (after Keith Stanovich and Richard West) System 1 (fast), the part of our brain responsible for a long list of chores, perhaps as much as 90% of its activity. Here are a few of them, from least to most complex:

- Detect that one object is more distant than another.

- Orient to the source of a sudden sound.

- Complete the phrase “bread and…”

- Make a “disgust face” when shown a horrible picture.

- Detect hostility in a voice.

- Answer to 2 + 2 = ?

- Read words on large billboards.

- Drive a car on an empty road.

- Find a strong move in chess (if you are a chess master).

- Understand simple sentences.

- Recognize that a “meek and tidy soul with a passion for detail” resembles an occupational stereotype. (Kahneman, 2011, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kindle locations 340-347).

System 2 (slow) is responsible for "paying attention," for giving attention to mental activities that require our awareness and focus - consequently, these activities are disrupted if our attention drifts or we are interrupted. For example:

- Brace for the starter gun in a race.

- Focus attention on the clowns in the circus.

- Focus on the voice of a particular person in a crowded and noisy room.

- Look for a woman with white hair.

- Search memory to identify a surprising sound.

- Maintain a faster walking speed than is natural for you.

- Monitor the appropriateness of your behavior in a social situation.

- Count the occurrences of the letter a in a page of text.

- Tell someone your phone number.

- Park in a narrow space (for most people except garage attendants).

- Compare two washing machines for overall value.

- Fill out a tax form.

- Check the validity of a complex logical argument. (Kahneman, Kindle locations 363-372)

System 2, which is also equivalent in some ways to working memory (the very brief memory capable of holding about 7 discrete objects at a time), is generally what we think of when we think of reasoning or of consciousness. Importantly, for this discussion, "

System 2 has some ability to change the way System 1 works, by programming the normally automatic functions of attention and memory" (Kahneman, Kindle Locations 374-375).

Whenever we are asked to do something - or choose to do something (like a crossword puzzle) - that we do not normally do, we will likely discover that maintaining a mindset for that task will require focus and at least a little bit of effort to stay on task. Nearly (if not all) novel activities to which we devote attention will require effort at first.

In terms of our evolution, this was no doubt true of thinking. At some point in our species' evolution our brains made the declarative transition from unconscious processing and processes to being able to think about our actions or our needs (hunger, sex, warmth, and so on).

Stewart offers the example of thinking skills to demonstrate how the declarative transition may have occurred:

A

clear example is provided by the evolution of thinking skills. As with

all skills, when thinking first arose, the processes that shaped and

structured sequences of thought would have been adapted procedurally.

Although the content of thought was declarative, the skills that

regulated the pattern of thought were procedural. Individuals would

discover which particular structures and patterns of thought were useful

in a particular context by what worked best in practice. They would not

have declarative knowledge that would enable them to consciously model

alternative thinking strategies and their effects. Thinking skills were

learnt procedurally, and there were no theories of thought, or thought

about thinking.

The development of declarative

knowledge about thinking strategies enabled existing thinking skills to

be improved and to be adapted to meet new requirements. In particular,

it eventually enabled an explicit understanding of what constituted

rational and scientific thought, and where and why it was superior. The

declarative transition that enabled thinking about thinking was a major

transition in human evolution that occurred on a wide scale only within

recorded history (see Turchin (1977) and Heylighen (1991) who examine

this shift within the framework of metasystem transition theory). This

transition remains an important milestone in the development of

individuals, and broadly equates to the achievement of what Piaget

referred to as the formal operational stage (Flavell 1985). However,

many adults still do not reach this level (Kuhn et al. 1977).

This was no doubt one of the momentous leaps in our evolution, probably only second to the rise of self-awareness, to think about thinking, to observe our actions and thoughts from a third-person perspective. That last transition still has not happened for a lot of people who have developed beyond concrete thinking. Along this line, each new increase in the number of perspectives we can take stretches our cognitive skills in new directions.

Stewart suggests that there are still declarative transitions awaiting us.

Clearly, humans as yet have limited declarative knowledge about the central processes that produce consciousness, and little capacity to model and adapt these processes with the assistance of declarative knowledge. (p. 8)

Stewart addresses two of these systems in his paper, (1) the hedonic system and (2) the processes act as a switchboard to decide when the global workspace (consciousness) is occupied by "structured sequences of thought and images."

The hedonic system is almost a stand-in for Freud's id. The hedonic system tells us what we like and dislike, what we want or need, what we desire, and what things we are motivated to do.

Although the hedonic system is the central determinant of what individuals do from moment to moment in their lives, it is not adapted to any extent with declarative knowledge. Individuals generally do not choose deliberatively what it is that they like or dislike, what they desire, or what they are motivated to do. They largely take these as given. They cannot change at will the impact of their desires, motivations and emotions on their behaviour, even when they see that the influence is maladaptive.

Most of what is in the hedonic system has been determined by natural selection or by classical conditioning during our individual development. The point is, however, that is functions as procedural knowledge, or as System 1 thinking. While we would like to think that we are rational creatures and reason out decisions such as who to vote for or what car to buy, more likely these decisions are made by the hedonic system and then, if we need to explain why, we generate a rational explanation for the choice (

De Martino, Kumaran, Seymour, and Dolan, 2006).

The other system Stewart addresses is the "switchboard" that determines when consciousness is occupied by structured thought or image sequences - thinking, planning, or worrying, for example.

These structured sequences take consciousness ‘off line’ by loading its limited capacity for the duration of the sequence. While a sequence unfolds, it largely precludes the recruitment by consciousness of resources relevant to other adaptive needs.

Declarative modelling appears to have little input into whether an individual engages in a structured sequence of thought in particular circumstances. It is not something that individuals generally deliberate about or have detailed theories about. We do not, for example, decide whether to engage in a sequence of thought on the basis of declarative knowledge about what is optimal for our adaptability in particular circumstances. Nor is it something that is usually under voluntary control. In fact, we cannot voluntarily stop thought for extended periods as a simple experiment demonstrates—if we attempt to remain aware of the second hand of a watch while we stop thought, we find that sequences of thought will soon arise and fully load consciousness, ending our awareness of the second hand. (p. 10-11)

This last example is familiar to anyone who meditates. Trying to keep our attention focused on the breath is like trying to make a wild monkey sit still (thus the term monkey-mind).

There are a lot of implications for this second issue that Stewart brings to the discussion, but here are three to feel relevant to me.

1) Free will - if we have it or not - will largely depend on our ability to choose what is in our awareness and then to use that skill to monitor and override the hedonic system.

2) In PTSD, one of the greatest challenges for survivors is that memories or flashbacks invade the global workspace and then play themselves out, sometimes on auto-repeat, and there is little the person can do to make it stop (well, there are grounding techniques, but they are somatic-level interventions, which may be the best way to get us out of our minds anyway).

3) Anxiety disorders generally feature a repetitious cognitive script that has a rather unique ability to draw in every situation that has ever gone badly as support for the current anxiety. The script (or as I prefer to understand it, the part) serves the purpose of keeping the person safe, but it does so to the detriment of the person's current life.

Each of those three points are reasons why I think GWT has a lot to add to how we do therapy - not just to how we might evolve our own consciousness.

In the next installment in the this series, we will look at each of these potential declarative transitions in a lot more detail.