The gap between atheists and the religious seems at times to be an

impossible divide, almost as if believers and non-believers come from

different species. What separates the secular from the sacred? An

"Ask the Brains" question on the

Scientific American

site recently inquired as to any differences between the brain of an

atheist and the brain of a religious person. Andrew Newberg, the

director of research at the Myrna Brind Center of Integrative Medicine

at Thomas Jefferson University and Hospital in Philadelphia, responded

that, yes, in fact, there are some small but perceptible differences

between the brains of believers and non-believers. Newberg is a pioneer

in the field of "neurotheology," the study of

how the brain approaches faith.

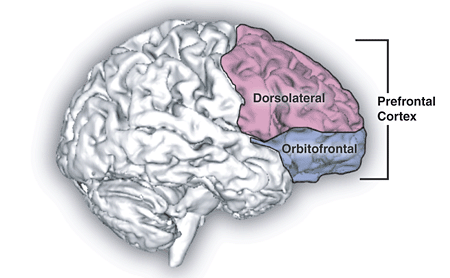

For

example, the frontal lobe of the brain governs reward, attention, and

motivation. In past studies, those who meditate or pray regularly seem

to have more active frontal lobes on average than those who do not.

Meditation has even been shown to

grow the frontal lobe. Newberg's own research has measured

changes in cerebral blood flow among Franciscan nuns as they prayed in a meditative fashion, finding an significant increase in activity in the frontal lobe as well.

The hippocampus is the center of memory and navigation in the brain;

recent research from Duke University

shows that people who have had a "born-again" experience showed more

atrophy of the hippocampus on average than the religious who didn't

identify as born-again. Research also suggests that the religious brain

has higher levels of dopamine (the hormone associated with motivation,

reward, and dozens of other processes) than the non-religious brain. But

does the belief cause the brain changes, or does the brain initiate the

impulse to believe?

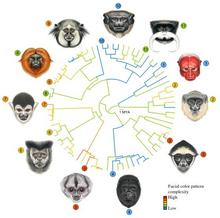

The human tendency to believe in the

supernatural may have its roots in the development of language, or in

our capacity to assign minds and actions to others, known as

the theory of mind.

How it evolved is up for debate, but the ritual burial practices of our

Paleolithic ancestors imply that it has been around as long as humanity

itself, becoming

increasingly more complex with time.

The stunning cave art found in Lascaux or Chauvet seems to have served

some sort of ritual purpose as well. As humanity stabilized into

sedentary populations after the neolithic revolution, organized religion

began to take over in small pockets of civilization, spreading as the

associated cultures began to increase in influence and power. The

stunning megaliths at

Göbekli Tepe,

the 12,000 year-old structure on a hilltop in Turkey, may even suggest

that the religious impulse was instrumental in the development of human

society.

But the effects of religion may also pertain to the present day. A recent study finds that the religious

tend to have higher self-esteem and are better adjusted

psychologically than the non-religious. The catch? This finding only

held true in countries that put a high value on religion. Perhaps for

these people, the value in religion is not in having faith itself, but

in the social capital that comes with it in a pious society. This

finding is reinforced by

research done with senior women

with and without a faith-based support network. But is religion just an

old-fashioned social network in a world full of new social

opportunities? After all, about 15 percent of Americans identify as

having

no religious affiliation, and the number seems to be growing.

All of which leads us to an interesting point, in terms of the future of humanity. As Kiwi researcher James Flynn discovered,

humanity’s IQ is increasing rather dramatically. This is probably due to increased nutrition, better early education, and a much more stimulating environment.

Research also suggests that the progression will slow and finally stop as it reaches its higher end—

Homo sapiens

can only get so smart. But this intelligence maximum would still

represent most of humanity possessing an IQ on something of the order of

(measured in today’s numbers) 140. In other words, someday we may be

living on a planet of geniuses, assuming that we are able to provide

enough food, medicine, and education.

We also know that as IQs rise, there tends to be

a corresponding rise in atheism.

It seems that the smarter a person is, the less likely he or she is to

believe in a god. Does this mean that humanity is destined to shed the

belief in a higher power like some sort of vestigial tail? Will we

become a planet of brilliant secular humanists? Nobody knows, of course,

but it is interesting to note that there are some countervailing forces

at work.

Spiritual beliefs may not only help individuals

survive, but there is evidence that religion plays a strong role in

group survival as well. In a study of several hundred historical

American intentional communities, University of Connecticut

anthropologist Richard Sosis found that secular groups were four times

more likely to disappear per year than groups founded on religious

principles. And in a further study that focused on just the religious

groups, Sosis found a direct correlation between the number of religious

rules placed on members and the longevity of the group as a whole. The

stricter the rules, the longer the community lasted. Strictures that

were placed on members of secular communities held no such power. “

Dr Sosis therefore concludes

that ritual constraints are not by themselves enough to sustain

co-operation in a community—what is needed in addition is a belief that

those constraints are sanctified.”

Might future atheist cultures

be less fit than the religious societies next door? Or is there a form

of belief or spiritual practice that is suitable for atheists? As

Professor Newberg noted in his answer cited above, we can reap many of

the benefits of the spiritual brain with

mindfulness meditation,

a practice suited for even the most ardent atheist. Or perhaps

mythology will give way to elegant metaphysics, creating a sort of

Religion 2.0, wherein authority comes from reason and philosophy instead

of the supposed revelations of a divine being. Duke University

philosopher Owen Flanagan recently published an article titled

"Buddhism Without the Hocus-Pocus,"

proposing that religious Buddhism dispense with all supernaturalism

(such as the concepts of karma and reincarnation), and inscribe the

ethical and epistemological aspects of the faith onto a naturalistic,

non-theistic background.

Throughout human history religion has

helped us to understand our world and to form effective groups based on a

shared ideology. Though Western society is becoming increasingly more

secular, the power of a shared faith to mobilize groups is obvious from

Palestine to Tibet. We may not necessarily be hardwired for mystical

experiences, but we are hardwired to benefit from a robust belief system

shared by our peers and a contemplative spiritual practice, even if not

necessarily a theistic one. Where we're headed is unlikely to be

completely sacred, but it's probably not going to be entirely profane,

either.

One option to consider:

David Eagleman’s Possibilianism.

Q: Why did you write the book?

Q: Why did you write the book?