Read the whole article.One of the knottier problems in evolutionary theory is altruism, because if you sacrifice yourself for someone else it would seem that you are helping someone else get their genes into the next generation at the cost of your own evolutionary heritage, and thus true altruism would seem to be anti- or non-Darwinian. And yet there are examples of animals (including human animals) who make such sacrifices. How do evolutionary biologists explain this mystery? There are several interesting answers that have been proposed since Darwin's time.

In this week’s eSkeptic, our regular contributor Kenneth Krause reviews the latest research on altruism, most notably that of primate research in controlled experiments in which both monkeys and apes are given choices to cooperate or compete against game partners in exchange scenarios, with implications for human research in this area.

Krause is contributing science editor for the Humanist and books editor for Secular Nation. He has recently contributed to Skeptical Inquirer, Free Inquiry, Skeptic, Truth Seeker, Freethought Today, Wisconsin Lawyer, and Wisconsin Political Scientist as well.

Doubting Altruism

New research casts a skeptical eye

on the evolution of genuine altruismby Kenneth W. Krause

As we soar into an inspiring new era of genomics, genetic manipulation, and, potentially, the directed evolution of our own species, naturalists urge us to remain partially grounded — to keep digging for long-buried evidence of key pre-historical developments. In so doing, however, the world’s leading anthropologists and primatologists have immersed themselves in a now-roiling debate over the origins of human morality in general and altruism in particular.

Some say that altruism — sometimes referred to as “other-regarding preferences” or “unsolicited prosociality” — is nothing more than a veneer, a cultural innovation humans alone have achieved in order to collectively restrain each individual’s natural proclivity to serve only herself, her close genetic relatives, and those who have demonstrated an adequate inclination to reciprocate to her eventual benefit. For these folks, no act can be characterized as wholly unselfish.

Others argue that altruism is more primitive than culture and, in fact, considerably more ancient than the human species itself. Other-regarding preferences, they say, are deeply innate, predating even the phylogenetic split that occurred six million years ago among the common ancestors of chimps and bonobos on the one hand and all species of hominid on the other. According to this camp’s credo, selflessness is as natural as appetite.

One line of experiments has confronted the issue directly, inquiring whether non-human primates will seize opportunities to assist others. In 2005, for example, UCLA anthropologist Joan Silk and others chose 18 chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) as the subjects of two such experiments, conducted in Louisiana and Texas.1 Chimps are among the primates most likely to exhibit unsolicited prosocial behavior, they reasoned, because in the wild they regularly hunt, patrol, and mate-guard cooperatively.

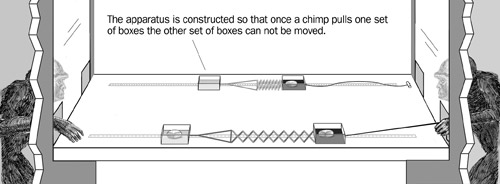

In each study, subject chimps were allowed to deliver food to other chimps, or “conspecifics,” at no cost to themselves. The test apparatuses provided each confined subject with two options — the 1/0 choice where it could acquire food only for itself, and the 1/1 choice where it could obtain food for both itself and its separately caged partner. As an essential control, acting chimps were given the same options with no partners present (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A test apparatus providing a subject with two options: acquire food only for itself (1/0), or obtain food for both itself and its separately caged partner (1/1).

Silk’s team predicted that if chimps are truly altruistic they should choose the 1/1 option more often than the 1/0 option when a conspecific is there to benefit. But that wasn’t the case. In Louisiana, not one of the seven subjects chose the 1/1 option significantly more often when partnered. In Texas, the remaining 11 actors went with both the 1/1 and the 1/0 option an average of only 48 percent of the time when another chimp was present.

“The absence of other-regarding preferences in chimpanzees,” the authors inferred, “may indicate that such preferences are a derived property of the human species tied to sophisticated capacities for cultural learning, theory of mind, perspective taking and moral judgment.” Nevertheless, Silk’s team remained open to the prospect that altruism might be detected among primates that, in some crucial ways, were even more cooperative than chimps. We will consider that possibility later.

Altruism’s Alter-Ego

A closely related line of experiments has tackled the same issue from a different direction, asking instead whether primates display a rudimentary sense of fairness in some form of “inequity aversion” (IA). If an animal reacts negatively to its own relative overcompensation, we say it has demonstrated some sensitivity to “advantageous inequity.” If it merely responds to a conspecific’s superior gain, on the other hand, the animal has shown aversion only to “disadvantageous inequity.”

The former inclination probably evolved after (and, morally speaking, is emphatically more advanced than) the latter because an animal sensitive to its own advantage can demonstrate not only an egocentric expectation of how it should be treated, but also a communal expectation of how all members of its species should be treated. In either case, if test subjects attempt to restore equity by sacrificing their own gains — even if only to simultaneously and unceremoniously deny superior gains to their luckier partners — according to many (but not all) researchers, they have nonetheless acted altruistically.

In 2003, Emory University primatologists Sarah Brosnan and Frans de Waal developed token exchange experiments where tufted capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) were measured for their reactions to situations in which their partners received greater food rewards.2 In the end, shortchanged subjects proved less likely to complete exchanges for identical tokens, and withdrew even more frequently when their partners received prizes for no tokens at all. These now-classic results have been widely interpreted as formidable evidence of disadvantageous IA in primates.

Two years later, Brosnan, de Waal, and Hillary Schiff released the outcomes of a similar study of adult chimpanzees.3 In order to distinguish the effects of social alignment, the team chose four animals that had lived continuously in pairs and 16 others that had been housed together at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center in Atlanta, Georgia for either 30 years or eight years prior to testing. As in the 2003 experiment, subjects were given tokens — in this case, rather useless and nondescript chunks of white PVC pipe — which they had been trained to return for either cucumber slices (the low-value reward) or grapes (the high-value reward).

During the inequity test, examiners initially allowed the partner chimps to exchange for a juicy, delicious grape — while eager subjects observed, of course — and then offered the subjects a relatively dry and no doubt disappointing cucumber slice. The examiners diligently recorded the subjects’ reactions, noting whether they had accepted or rejected their prizes. Brosnan discovered first that, when the tables were turned, subjects did not react negatively when given a superior reward and, thus, were likely not averse to advantageous inequity. Whether such a finding actually distinguished chimpanzees from humans in any meaningful way, the authors noted, was questionable.

Second, according to Brosnan, the results confirmed that disadvantageous IA was “present and robust” among chimpanzees, although to significantly different degrees depending on each subject’s social history. Chimps that had lived in pairs or in relatively novel groups reacted most intensely, while animals from older, more tightly-integrated groups appeared more accepting of inequity — all of which could be entirely consistent with human predilections to either “make waves” or “go with the flow,” depending primarily on their social milieu. Tolerance of inequity, Brosnan suggested, may be more a function of group size and intimacy than either moral choice or any isolated cognitive factor. So by the end of 2005, very little if anything had been truly settled. The experiments would continue and become ever more creative and exacting, but the already muddied anthropological waters would grow more cluttered and murkier still.

Offering multiple perspectives from many fields of human inquiry that may move all of us toward a more integrated understanding of who we are as conscious beings.

Thursday, February 12, 2009

The Skeptic - Doubting Altruism

Altruism is one of those things that evolutionary psychologists and biologists love to fight about. Altruism poses some serious problems to the idea that organisms are devoted to protecting and promoting their own gene line, as Dawkins argued in The Selfish Gene. This article looks at the issue in a less than favorable light, so take this as one for the "against" side of the debate.

Tags:

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment