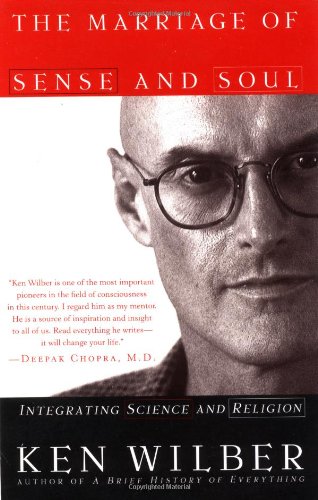

This essay from Dr Jonathan Rowson, Director, RSA Social Brain Centre, was published back in July on the RSA site. Somehow I missed it then. In essence, this essay states the problem and offers a solution - from which they will develop workshops and other events through to test their model. And for what it's worth, it is a very Wilberian model. although his name is not mentioned at all in this essay (from The Marriage of Sense and Soul: Integrating Science and Religion, 1998). Here is a passage:

The spiritual injunction is principally an experiential one, namely to know oneself as fully as possible. For many, that means beginning to see beyond the ego and recognise oneself as being part of a totality, or at least something bigger than oneself.These sentences resemble similar lines one might find in Ken Wilber's The Marriage of Sense and Soul, so it would be nice to credit the source, even if only in passing.

Such self-knowledge is a deeply reflexive matter. The point is not to casually introspect, but rather to strive to connect our advanced third-person understanding of human nature with a growing skill in observing how one’s first-person nature manifests in practice, and to test the validity and relevance of this experience and understanding in second-person contexts. In this sense, spirituality is about I, we and it, and this process of trying to know oneself more fully, both in understanding and experience, is therefore no mere prelude to meaningful social change, but the thing itself.

It will be interesting to see how they implement these ideas in practice over the coming year.

The Brains Behind Spirituality

July 22, 2013 by Jonathan Rowson

Filed under: Social Brain

The Summer issue of the RSA Journal features the following essay outlining the intellectual context for a new project by the Social Brain Centre. We are examining how new scientific understandings of human nature might help us reconceive the nature and value of spiritual perspectives, practices and experiences. Our aim is to move public discussions on such fundamental matters beyond the common reference points of atheism and religion, and do so in a way that informs non-material aspirations for individuals, communities of interest and practice, and the world at large.

We are currently completing our background research for a series of forthcoming workshops and public events, culminating in a final report in 2014.

The Brains Behind Spirituality

Immanuel Kant said that the impact of liberal enlightenment on our spiritual life was such that if somebody were to walk in on you while you were on your knees praying, you would be profoundly embarrassed. That imagined experience of embarrassment is still widely felt in much of the modern western world, not merely for religious believers, but for the silent majority who consider themselves in some sense ‘spiritual’ without quite knowing what that means. This sense of equivocation is felt when we hear the term ‘spiritual’ referred to apologetically in intellectual contexts. Consider, for instance, ‘the mental, emotional or even spiritual qualities of the work’, or ‘the experience was almost spiritual in its depth and intensity’.

This unease with public discussions of spirituality is not universal and clearly varies within and between countries. Perhaps the embarrassment is a peculiar affliction of western intellectuals, since ‘spiritual’ appears to convey shared meaning perfectly well in ordinary language throughout most of the world. This intellectual unease matters because spiritual expression and identification is an important part of life for millions of people. But it currently remains ignored because it struggles to find coherent expression and, therefore, lacks credibility in the public domain.

Andrew Marr astutely opened a recent BBC discussion by referring to the “increasingly hot-tempered public struggle between religious believers and so-called militant atheists, and yet many, perhaps most people, live their lives in a tepid confusing middle ground between strong belief and strong disbelief”. There is some empirical backing for this claim. Post-Religious Britain: The Faith of the Faithless, a 2012 meta-analysis of attitude surveys by the thinktank Theos, revealed that about 70% of the British population is neither strictly religious nor strictly non-religious, but rather moving in and out of the undesignated spaces in between. While the power of organised Christian religion may be in decline, only about 9% are resolutely atheistic, and it is more accurate to think of an amorphous spiritual pluralism that needs our help to find its form.“many, perhaps most people, live their lives in a tepid confusing middle ground between strong belief and strong disbelief” – Andrew Marr

The point of rethinking spirituality is not so much to challenge these boundaries, but to clarify what it means to say that the world’s main policy challenges may be ultimately spiritual in nature. When you consider how we might, for instance, become less vulnerable to terrorism, care for an ageing population, address the rise in obesity or face up to climate change, you see that we are – individually and collectively – deeply conflicted by competing commitments and struggling to align our actions with our values. In this respect, we are relatively starved for forms of practice or experience that might help to clarify our priorities and uncover what Harvard psychologist Robert Kegan calls our immunity to change. The best way to characterise problems at that level is spiritual.

There are so many dimensions to spirituality that it is necessary to qualify what we are talking about. Personally, I think of it principally as the lifelong challenge to embody one’s vision of human existence and purpose, expressed most evocatively in Gandhi’s call to be the change you want to see in the world. Others may place greater emphasis on the forms of experience that inspire the changes we want to see, or the realities we need to accept.

Being spiritual can mean safeguarding our sense of the sacred, valuing the feeling of belonging or savouring the rapture of intense absorption. And then there is the quintessential gratitude we feel when we periodically notice, as gift and revelation, that we are alive.Personally, I think of the spiritual principally in terms of the lifelong challenge to embody one’s vision of human existence and purpose, expressed most evocatively in Gandhi’s call to be the change you want to see in the world.

Such experiences do not depend upon doctrine or on institutional endorsement or support. They are as likely to arise listening to music, walking in nature, celebrating the birth of a child, reflecting on a life that is about to end, or losing oneself – in a good sense – in the crowd. With such a rich range of dimensions, it is regrettable that spirituality is still framed principally through the prism of organised religion. But it is perhaps no less unfortunate that those who value spiritual experience and practice are often suspiciously quick to disassociate themselves from belief in God and religion, as if such things were unbearably unfashionable and awkward, rather than perhaps the richest place to understand the nature of spiritual need.

Spiritual but not religious

While there has been a growing normalisation of the idea that a person can be ‘spiritual but not religious’, this designation may actually compound the problem of intellectual embarrassment. It does nothing to clarify what spirituality might mean outside of religious contexts, nor how religion might valuably support and inform non-believers. People in this category get attacked from both sides; from atheists for their perceived irrationality and wishful thinking, and from organised religion for their rootless self-indulgence and lack of commitment. And the category of spiritual but not religious hardly does justice to the myriad shades of identification and longing within it and outside it. What are we to make, for instance, of the fact disclosed in the same Theos report, that about a quarter of British atheists believe in human souls?

Such findings highlight that spiritual embarrassment is grounded in confusion about human nature and human needs. We struggle to speak of the spiritual with coherence mostly because it has been subsumed by historical and cultural contingency, and is now smothered in an uncomfortable space between religion and the rejection of religion. Surely religions are the particular cultural, doctrinal and institutional expressions of human spiritual needs, which are universal? In this respect, is it not the sign of a spiritually degenerate society that many feel obliged to define their fundamental outlook on the world in such relativist and defensive terms? Compare the designations: ‘educated, but not due to schooling’ or ‘healthy, but not because of medicine’.

There must be a better place to begin the inquiry. The categorisation spiritual but not religious still tacitly assumes the most important question to interrogate is which version of reality we should subscribe to, rather than what it might mean to grow spiritually in a societal context where for most people belief in God need feel neither axiomatic nor problematic. The writer Jonathan Safran Foer highlighted the depth of this point on BBC Radio 4’s Start the Week programme when he responded to the question of what he believed by saying: “I’m not only agnostic about the answer, I’m agnostic about the question.”

Reconceiving spirituality

One major challenge in making the spiritual more tangible and tractable is, therefore, to enrich our currently impoverished idea of what it means to believe. To believe something is often assumed to mean endorsing a statement of fact about how things are, but that is both outdated and unhelpful.

Consider the story of two rabbis debating the existence of God through a long night and jointly reaching the conclusion that he or she did not exist. The next morning, one observed the other deep in prayer and took him to task. “What are you doing? Last night we established that God does not exist.” To which the other rabbi replied, “What’s that got to do with it?”

The praying non-believer illustrates that belief may be much closer to what the sociologist of religion William Morgan described as “a shared imaginary, a communal set of practices that structure life in powerfully aesthetic terms”. Within the same discipline Gordon Lynch suggests this point needs deepening: “The unquestioned status of propositional models of belief within the sociology of religion arguably reflects a lack of theoretical discussion… about the nature of the person as a social agent.”

It is therefore time to question the common default position that emphasises the autonomous individual striving to consciously construct their own religious belief system as a guide to how they should act in the world. It is not just about sociality. The emerging early 21st century view of human nature indicates we are fundamentally embodied, constituted by evolutionary biology, embedded in complex online and offline networks, largely habitual creatures, highly sensitive to social and cultural norms, riddled with cognitive quirks and biases, and much more rationalising than rational.

Such a shift in perspective is important because every culturally sanctioned form of knowledge contains an implicit injunction. The injunction of science is to do the experiment and analyse the data. The injunction of history is to critically engage with primary and secondary sources of evidence. The injunction of philosophy is to question assumptions, make distinctions and be logical. If spirituality is to be recognised as something with ontological weight and social standing, it also needs an injunction that is culturally recognised, as it was for centuries in the Christian west and still is in many societies worldwide.It is time to question the common default position that emphasizes the autonomous individual striving to consciously construct their own religious belief system as a guide to how they should act in the world.

The spiritual injunction is principally an experiential one, namely to know oneself as fully as possible. For many, that means beginning to see beyond the ego and recognise oneself as being part of a totality, or at least something bigger than oneself.

Such self-knowledge is a deeply reflexive matter. The point is not to casually introspect, but rather to strive to connect our advanced third-person understanding of human nature with a growing skill in observing how one’s first-person nature manifests in practice, and to test the validity and relevance of this experience and understanding in second-person contexts. In this sense, spirituality is about I, we and it, and this process of trying to know oneself more fully, both in understanding and experience, is therefore no mere prelude to meaningful social change, but the thing itself.

There are many ways to illustrate how new conceptions of human nature might revitalise our appreciation for the spiritual. The psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist’s work on the competing worldviews of the two brain hemispheres offers a new perspective on the challenge of creating balance in one’s thought and life. Daniel Kahneman, the Israeli-American psychologist, has suggested that we can’t really do anything about our innumerable cognitive frailties, but this questionable claim is challenged by mindfulness practices, where we can see and feel the root cause of some of our mental tendencies and biases more viscerally. And cognitive scientists George Lakoff and Mark Johnson’s idea that thinking is fundamentally grounded in bodily metaphors gives us new appreciation for our need to be touched, moved or inspired on a regular basis.The spiritual injunction is principally an experiential one, namely to know oneself as fully as possible.

The point of reconsidering spirituality through such lenses is not to explain away spiritual content. We do not want to collapse our deliciously difficult existential and ethical issues into psychological and sociological concepts. The point is rather to explore the provenance of those questions and experiences with fresh intellectual resources.

Returning to Kant, if enlightenment in his view was about humanity emerging into adulthood, one corollary is that unquestioning subservience to organised religion may now be condemned as immature. However, the deeper implication is that we need to rediscover or develop mature forms of spirituality, grounded both in what we can never really know about our place in the universe, and what we can know – and experience – about ourselves.

By Dr Jonathan Rowson, Director, RSA Social Brain Centre. Follow @Jonathan_Rowson

No comments:

Post a Comment