No drug has done more to ease the suffering of depression than Prozac. And no drug has done more to move the science in the wrong direction than this same drug.

From The Boston Globe:

Head FakeRead the rest.

How Prozac sent the science of depression in the wrong direction

By Jonah Lehrer

July 6, 2008PROZAC IS ONE of the most successful drugs of all time. Since its introduction as an antidepressant more than 20 years ago, Prozac has been prescribed to more than 54 million people around the world, and prevented untold amounts of suffering.

But the success of Prozac hasn't simply transformed the treatment of depression: it has also transformed the science of depression. For decades, researchers struggled to identify the underlying cause of depression, and patients were forced to endure a series of ineffective treatments. But then came Prozac. Like many other antidepressants, Prozac increases the brain's supply of serotonin, a neurotransmitter. The drug's effectiveness inspired an elegant theory, known as the chemical hypothesis: Sadness is simply a lack of chemical happiness. The little blue pills cheer us up because they give the brain what it has been missing.

There's only one problem with this theory of depression: it's almost certainly wrong, or at the very least woefully incomplete. Experiments have since shown that lowering people's serotonin levels does not make them depressed, nor does it does not make them depressed, nor does it worsen their symptoms if they are already depressed.

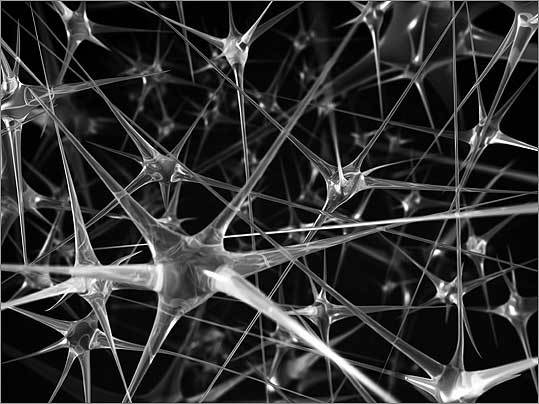

In recent years, scientists have developed a novel theory of what falters in the depressed brain. Instead of seeing the disease as the result of a chemical imbalance, these researchers argue that the brain's cells are shrinking and dying. This theory has gained momentum in the past few months, with the publication of several high profile scientific papers. The effectiveness of Prozac, these scientists say, has little to do with the amount of serotonin in the brain. Rather, the drug works because it helps heal our neurons, allowing them to grow and thrive again.

In this sense, Prozac is simply a bottled version of other activities that have a similar effect, such as physical exercise. They aren't happy pills, but healing pills.

These discoveries are causing scientists to fundamentally reimagine depression. While the mental illness is often defined in terms of its emotional symptoms - this led a generation of researchers to search for the chemicals, like serotonin, that might trigger such distorted moods - researchers are now focusing on more systematic changes in the depressed brain.

"The best way to think about depression is as a mild neurodegenerative disorder," says Ronald Duman, a professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at Yale. "Your brain cells atrophy, just like in other diseases [such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's]. The only difference with depression is that it's reversible. The brain can recover."

Given the prevalence of depression - more than 16 percent of people will suffer from a major depressive episode at some point in their lives - a more accurate scientific understanding of the disease is of immense value. In fact, this research is already being used to develop more effective treatments for the mental illness, some of which are currently in clinical trials.

The progress exemplifies an important feature of modern medicine, which is the transition from a symptom-based understanding of a disease - depression is an illness of unrelenting sadness - to a more detailed biological understanding, in which the disease is categorized and treated based on its specific anatomical underpinnings.

It now appears that many of the most effective antidepressants are actually helping heal the brain, not merely increasing temporary levels of serotonin or other neurotransmitters. The more we understand about these processes, the better able we will be to treat these illnesses.

And for the record, I'm not a drug only guy -- I firmly believe that psychotherapy can sometimes do the same work, though slower. However, sometimes a client needs to be stabilized with drugs before therapy can be effective. Most times, a mixed approach, along with diet (omega-3 fats) and exercise is the best approach (some might call it integral).

For another take on this article, see Another Brain Fad for Depression?, by [Hat tip to Bob for the link.]

2 comments:

Bill,

Check out this insightful commentary on the Boston Globe article, if you haven't already seen it.

Another Brain Fad for Depression?

Thanks Bob -- I'll update the post with that link.

Peace,

Bill

Post a Comment