Evan Thompson's new book is Waking, Dreaming, Being: Self and Consciousness in Neuroscience, Meditation, and Philosophy (2014). I'm only about 4 chapters into it at this point, but I find myself agreeing with Thompson's model of consciousness to a degree I did not anticipate. His "embodied, embedded, and relational" understanding of how consciousness functions is very similar to my own sense of consciousness.

Here are a couple of excerpts.

Moreover, the brain is always embodied, and its functioning as a support for consciousness can’t be understood apart from its place in a relational system involving the rest of the body and the environment. The physical substrate of mind is this embodied, embedded, and relational network, not the brain as an isolated system.[37]I also support his rejection of the premise that "consciousness has ontological primacy," an idea I see presented in Buddhist authors such as B Alan Wallace, Ken Wilber's integral theory, and most New Age misunderstandings of quantum mechanics (see Deepak Chopra and others of his ilk).

At the same time, we can’t infer from the existential or epistemological primacy of consciousness that consciousness has ontological primacy in the sense of being the primary reality out of which everything is composed or the ground from which everything is generated. One reason we can’t jump to this conclusion is that it doesn’t logically follow. That the world as we know it is always a world for consciousness doesn’t logically entail that the world is made out of consciousness. Another reason is that thinking that consciousness has ontological primacy goes against the testimony of direct experience, which speaks to the contingency of our consciousness on the world, specifically on our living body and environment. (p. 102)

Over the last several years, I have become enamored of the theory of consciousness as an emergent property of matter.

The term “emergence” comes from the Latin verb emergo which means to arise, to rise up, to come up or to come forth. The term was coined by G. H. Lewes in Problems of Life and Mind (1875) who drew the distinction between emergent and resultant effects.___

If we were pressed to give a definition of emergence, we could say that a property is emergent if it is a novel property of a system or an entity that arises when that system or entity has reached a certain level of complexity and that, even though it exists only insofar as the system or entity exists, it is distinct from the properties of the parts of the system from which it emerges.Thompson shares the emergentist position, with qualifications.

Is the view I’m presenting a version of “emergentism,” according to which consciousness is a higher-level property of living beings that emerges from lower-level biological and physical processes?[39] And if so, am I supposing that consciousness is scientifically explainable or presenting a version of “mysterianism,” the doctrine that says that the human mind is incapable of understanding how consciousness fits into the natural world?[40]In the following passage, Thompson dismisses both the dualism of Dharmakriti and the notion of interiority of particles, a premise of Wilber's AQAL model.

My view can be described as an emergentist one, in the following sense. I hold that consciousness is a natural phenomenon and that the cognitive complexity of consciousness increases as a function of the increasing complexity of living beings. Consciousness depends on physical or biological processes, but it also influences the physical or biological processes on which it depends. I also think the human

mind is capable of understanding how consciousness arises as a natural phenomenon, so I’m not a mysterian.

Nevertheless, my view differs from emergentism in its standard form, according to which physical nature, in itself, is fundamentally nonmental, yet when it’s organized in the right way, consciousness emerges. This view works with a concept of physical being that inherently excludes mental or experiential being, and then tries to show how consciousness could arise as a higher-level property of physical being so conceived. In my view, however, no concept of nature or physical being that by design excludes mental or experiential being will work to account for consciousness and its place in nature. (p. 103)

Recall that Dharmakīrti reasoned in the following way: matter and consciousness have totally different natures; an effect must be of the same nature as its cause; therefore, consciousness cannot arise from or be produced by matter. This argument rejects emergentism in its standard form, for it denies that physical nature, understood as being fundamentally or essentially nonmental, is suffcient to produce or give rise to consciousness. This aspect of Dharmakīrti’s argument is hardly antiquated, for a similar and very forceful argument against standard emergentism has recently been given by the philosopher Galen Strawson.[41] In both cases, the crucial insight is that the emergence of experiental being from physical being is unintelligible, given a concept of physical phenomena as fundamentally or essentially excluding anything mental or experiential.Thompson's point in Chapter Four, from which all of these quotes are taken, is to move the reader toward his primary philosophical position on consciousness, neurophenomenology.

Whereas Dharmakīrti used his argument to support a version of mind-body dualism, Strawson uses his argument to support “panpsychism.” Dualism says that matter and consciousness have totally different natures; panpsychism says that every physical phenomenon possesses some measure of experience as part of its intrinsic nature. Neither position is attractive to me. Dharmakīrti’s dualism, which allows for modes of consciousness not dependent on the brain, doesn’t sit well with the scientific evidence, as we’ve seen. Neither does Strawson’s panpsychism. This position attributes “micro-experiences” to microphysical phenomena, despite there being no evidence for protons or electrons having any experiences of their own. Not only does ascribing “micro-experiences” to physical particles seem ad hoc, but also it gives rise to the so-called “combination problem” of how it’s possible for “micro-experiences” to coexist or combine coherently in a human or other kind of animal subject. (p. 104-105)

Where does this leave us with regard to the project of relating consciousness to the brain, and more comprehensively, to our bodily being? Since we can’t step outside of consciousness or our embodiment, we need to work within them carefully and precisely. Instead of focusing mainly on the outward behavioral and physiological expressions of consciousness, we need to give equal attention to cultivating our experience from within. Concretely, this means we need to work with contemplative forms of mental training and embed them within a larger framework that also includes the experimental sciences of mind and life. Such a framework, in which both contemplative practice and scientific observation and measurement are seen as grounded in direct experience, is precisely what Francisco Varela had in mind when he introduced his research program of “neurophenomenology.”[43]Thompson, along with by Francisco J. Varela and Eleanor Rosch first laid out a definition of neurophenomenology in their seminal book, The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience (1991).

Neurophenomenology provides the framework for the rest of this book. (p. 105-106)

The following is an excerpt from Thompson's 2010 book, Mind in Life: Biology, Phenomenology, and the Sciences of Mind.

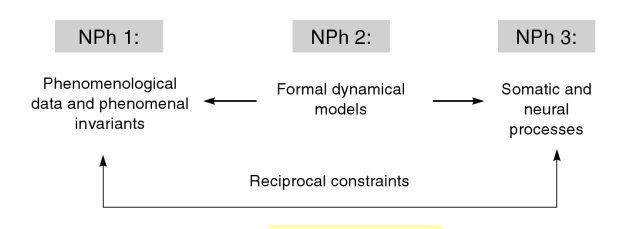

Varela formulates the “working hypothesis” of neurophenomenology in the following way: “Phenomenological accounts of the structure of experience and their counterparts in cognitive science relate to each other through reciprocal constraints” (1996. p. 343). By “reciprocal constraints” he means that phenomenological analyses can help guide and shape the scientific investigation of consciousness, and that scientific findings can in turn help guide and shape the phenomenological investigations. A crucial feature of this approach is that dynamic systems theory is supposed to mediate between phenomenology and neuroscience. Neurophenomenology thus comprises three main elements (see Figure 11.2): (1) phenomenological accounts of the structure of experience; (2) formal dynamical models of these structural invariants; and (3) realizations of these models in biological systems. Given that time-consciousness is supposed to be an acid test of the neurophenomenological enterprise, we need to see whether phenomenological accounts of the structure of time-consciousness and neurodynamical accounts of the brain processes relevant to consciousness can be related to each other in a mutually illuminating way. This task is precisely the one Varela undertakes in his neurophenomenology of time-consciousness and in his experimental research on the neurodynamics of consciousness.

Varela’s strategy is to find a common structural level of description that captures the dynamics of both the impressional-retentional-protentional flow of time-consciousness and the large-scale neural processes thought to be associated with consciousness. We have already seen how the flow of time-consciousness is self-constituting. What we now need to examine is how this self-constituting flow is supposed to be structurally mirrored at the biological level by the self-organizing dynamics of large-scale neural activity.

Figure 11.2- Neurophenomenology

I highly recommend all three of Thompson's books that are referenced here - he is one of the leading philosophers of mind working today.

There is now little doubt in cognitive science that cognitive acts, such as the visual recognition of a face, require the rapid and transient coordination of many functionally distinct and widely distributed brain regions. Neuroscientists also increasingly believe that moment-to moment, transitive (object-directed) consciousness is associated with dynamic, large-scale neural activity rather than any single brain region or structure (Cosmelli, Lachaux, and Thompson, 2007). Hence, any model of the neural basis of mental activity, including consciousness, must account for how large-scale neural activities can operate in an integrated or coherent way from moment to moment.

This problem is known as the large-scale integration problem (Varela et al. 2001). According to dynamical neuroscience, the key variable for understanding large-scale integration is not so much the activity of the individual neural components, but rather the nature of the dynamic links among them. The neural counterparts of mental activity are thus investigated at the level of collective variables that describe emergent and changing patterns of large-scale integration. One recent approach to defining these collective variables is to measure transient patterns of synchronous oscillations between different populations of neurons (Engel, Fries, and Singer 2001; Varela et al. 2001). According to Varela (1995, 1999), these synchrony patterns define a temporal frame of momentary and transient neural integration that corresponds to the duration of the present moment of experience.

No comments:

Post a Comment