There is a very interesting and entertaining interview with Ervin Laszlo in the new Integral Leadership Review, conducted by Antonio Marturano. Laszlo is one of the original integral theorists whose work Ken Wilber appropriated into his own model. In fact, Stan Grof compared László's work to that of Ken Wilber, saying, "Where Wilber outlined what an integral theory of everything should look like, Laszlo actually created one (Laszlo, 1993, 1995, 2004; Laszlo and Abraham, 2004)." [Stan Grof, A Brief History of Transpersonal Psychology, p. 14]

Laszlo is the author of The Connectivity Hypothesis: Foundations of an Integral Science of Quantum, Cosmos, Life, and Consciousness (2003), Science and the Reenchantment of the Cosmos: The Rise of the Integral Vision of Reality (2006), Science and the Akashic Field: An Integral Theory of Everything (2007), Quantum Shift in the Global Brain: How the New Scientific Reality Can Change Us and Our World (2008), and The Akasha Paradigm: Revolution in Science, Evolution in Consciousness (2012), among many, many other books (83).

Here is the beginning of the interview:

A Theory of Everything – Ervin Laszlo and Antonio MarturanoRead the whole interview.

Download article as PDF

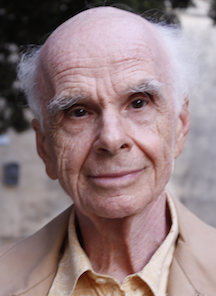

Ervin Laszlo

Antonio Marturano

I am pleased to have interviewed Prof. Ervin Laszlo who is a systems philosopher, integral theorist, and classical pianist. Twice nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, he has authored more than 70 books that have been translated into nineteen languages, and has published in excess of four hundred articles and research papers, including six volumes of piano recordings. Dr. Laszlo is generally recognized as the founder of systems philosophy and general evolution theory and serves as the founder-director of the General Evolution Research Group and as past president of the International Society for the Systems Sciences. He underscores the importance of developing a holistic perspective on the world and humankind, an outlook he refers to as “quantum consciousness”. He is also the recipient of the highest degree in philosophy and human sciences from the Sorbonne, the University of Paris, as well as of the coveted Artist Diploma of the Franz Liszt Academy of Budapest. Additional prizes and awards include four honorary doctorates. For many years he has served as president of the Club of Budapest, which he founded. He is an advisor to the UNESCO Director General, ambassador of the International Delphic Council, member of the International Academy of Science, World Academy of Arts and Science, and the International Academy of Philosophy.

I started my interview with Prof. Laszlo by asking him about his links with Italy. He explained that in his earlier years he was a pianist and so he gave concerts all over the World. His very first concert outside Hungary was in Italy. Since then, he developed a passion with Italy that led him to buy a house in Tuscany. So, Italy is still his favorite place.

I have also asked his opinion about whether Italy can provide good examples for leadership studies with its unique history and complexity. Laszlo replied that it is difficult for a particular form of leadership to emerge in Italy. Italy has a very long history and its social dynamics are quite complex. The result is that Italians are too individualistic and Italy has a very diverse culture. In Italy there coexists so many regional cultures that make this country a highly culturally complex society (reflected in its gastronomy, too), which cannot give raise to a homogeneous leadership style.

Antonio: Can you tell us something about your Theory of Everything?

Ervin: All things are co-evolving. This is how they evolved in time and in space, of course. In that sense I think you can have a theory of everything that is correct in relation to the main variety of observations that you have in science.

Antonio: So a Theory of Everything can be useful to study leadership, especially in those settings like in Italy where complexity, particularly culture complexity, is very important?

Ervin: Such a theory can provide general guidelines and can offer general concepts. Then the question is how you apply the information that you get from the theory, the insight that you get from the theory. How you apply it depends on the interpretation you give to that theory. But you can give general guidelines, because you can look at the relationship between subsystems and the overall system. You can see that a certain level of coherence between the subsystems is a requirement for the existence of the overall system – where you have detailed proper balance between integration and diversification, for example. All of these are guidelines that you can apply when you analyze the evolution of a complex system such as the culture in Italy.

Antonio: It would be interesting to understand your consideration of transdisciplinarity.

Ervin: Disciplines in science are artifacts; they are artificial. They are often necessary, but not always a satisfactory limitation on the number of observations and the number of facts that one takes into account. There are no boundaries in nature that correspond one to one with the boundaries of disciplines. For example life is not necessarily limited to biology, it’s also obviously evident in sociology and psychology. It also appears in the cosmos.

The way we can think about evolution is not limited to one kind of system. It appears from the big bang onwards all the way up to the evolution of consciousness, the evolution of the whole cosmos at the same time. So disciplines are a necessary self-restriction in science, but they should be considered as permeable, as transferrable and expandable boundaries that one keeps to as long as they are useful. When we can get over these boundaries, then it’s an improvement when you manage to overcome them.

Antonio: Is there any difference between transdisciplinarity and multidisciplinarity and the like?

Ervin: I think there is yes, but of course this is a question of definitions. Multidisciplinarity means several disciplines. Disciplines can be brought into conjunction with one another, but they are not brought together. They do not become a coherent whole. A theory that is transdisciplinary does not simply enumerate or place side-by-side different disciplines, but transcends them. That’s what the word says: transcend the different disciplines and show that they actually are so many different facets or local manifestations of the same phenomenon.

No comments:

Post a Comment