However, those actually working with the metals may have been the architects of the scientific method, the creation of a hypothesis, a test, and a record of the outcomes. Very cool.

Read the whole article.Good as gold

What alchemists got right

By Stephen Heuser, March 15, 2009THREE HUNDRED YEARS ago, more or less, the last serious alchemists finally gave up on their attempts to create gold from other metals, dropping the curtain on one of the least successful endeavors in the history of human striving.

Centuries of work and scholarship had been plowed into alchemical pursuits, and for what? Countless ruined cauldrons, a long trail of empty mystical symbols, and precisely zero ounces of transmuted gold. As a legacy, alchemy ranks above even fantasy baseball as a great human icon of misspent mental energy.

But was it really such a waste? A new generation of scholars is taking a closer look at a discipline that captivated some of the greatest minds of the Renaissance. And in a field that modern thinkers had dismissed as a folly driven by superstition and greed, they now see something quite different.

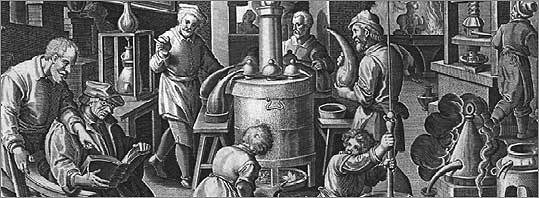

Alchemists, they are finding, can take credit for a long roster of genuine chemical achievements, as well as the techniques that would prove essential to the birth of modern lab science. In alchemists' intricate notes and diagrams, they see the early attempt to codify and hand down experimental knowledge. In the practices of alchemical workshops, they find a masterly refinement of distillation, sublimation, and other techniques still important in modern laboratories.

Alchemy had long been seen as a kind of shadowy forebear of real chemistry, all the gestures with none of the results. But it was an alchemist who discovered the secret that created the European porcelain industry. Another alchemist discovered phosphorus. The alchemist Paracelsus helped transform medicine by proposing that disease was caused not by an imbalance of bodily humors, but by distinct harmful entities that could be treated with chemicals. (True, he believed the entities were controlled by the planets, but it was a start.)

"We've got people who are trying to make medicines, which are pharmaceuticals; we've got people who are trying to understand the material basis of the world - very much like a modern engineer, or someone in technology," says Lawrence Principe, a professor of chemistry and the history of science at Johns Hopkins University who is a leading thinker in the revival of alchemy studies.

The field has begun to coalesce as its own academic specialty. Last fall, alchemy scholars gathered at their second academic conference in three years, and in January, Yale University opened an exhibit of rare alchemical manuscripts. For the first time, the leading academic journal of scientific history is planning to publish a special section on alchemy.

To Principe and his colleagues, there is a larger goal. Beyond rehabilitating the reputation of the historical thinkers who considered themselves alchemists, they hope to encourage a broader view of science itself - not as a starkly modern category of human achievement, but rather as part of a long and craftsmanlike tradition of trying to understand and manipulate nature.Alchemists might have been colossally wrong in their goals, but they were, in some fundamental way, part of the story of science, these scholars say. Robert Boyle and Sir Isaac Newton, fathers of modern chemistry and physics, were also serious students of alchemy. And the fact that alchemists have been marginalized as hand-waving mystics says less about alchemists themselves than about modern society's need to separate itself from the supposedly benighted past.

The roots of alchemy appear to touch nearly every developed culture - alchemists worked in the Far East, India, and the Islamic world. But it was in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries when alchemy reached its peak of influence, a network of respected and often well-paid specialists laboring in the towns and princely courts of Germany and Italy, as well as in Britain and France. Some alchemists were independent operators, perhaps an assayer in a mining town who hoped to create a little gold on the side; some ran workshops with a dozen apprentices under the patronage of aristocrats. "It's really a surprising range of people who got involved in alchemy in the 16th century," says Tara Nummedal, a historian of alchemy at Brown University. "Alchemy was really part of the popular culture."

What they all shared was a belief that one natural substance could be transmuted into another. An ancient theory of nature held that all matter was in a process of slow but constant change, and the mission of alchemy was to nudge that process along. The highest and purest state of matter was gold, and gold is what alchemists prized most. But even a partial success could yield a valuable material like tin, copper, or silver.

In many ways the alchemists made it easy for later scientists to dismiss them as tall-hatted cranks. Their notebooks are deliberately cryptic; they wrote under arcane pseudonyms and invented fictional authorities. They assumed vast, secret connections between planets and the spiritual world; they saw metals as an expression of the divine.

Even their most serious research was infused with beliefs and terms that sound more like wizardry than like modern lab science - the Philosopher's Stone, the Chemical Wedding, an invisible "vegetative spirit" that suffuses the earth. It is hard to imagine a modern scientist choosing to express his lab findings, as the distinguished German alchemist Michael Maier once did, in a set of 50 musical fugues for three voices, in which mythological characters represented the interacting elements.

That might seem impossibly distant from the idea of modern science, a world of hard data about discrete physical problems, ruled by observable and reproducible fact. But as scholars reexamine the roots of chemistry, they are now seeing less of a clean break than a subtle evolution from one craft to another. Alchemists tried and discarded theories, like scientists did; despite their occult reputation, they often saw themselves less as conduits to the supernatural than as analytical thinkers trying to accelerate and manipulate real physical processes.

No comments:

Post a Comment