Read the whole article."This Is the End of the Poem"

How Jack Spicer broke through the pieties of the avant-garde.

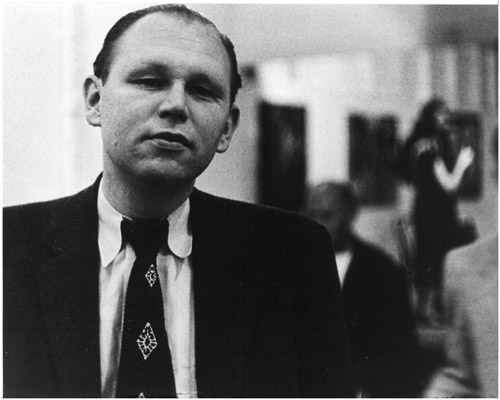

Jack Spicer at the opening of the 6 Gallery, 1954. Photo by Robert Berg.

When I first discovered Jack Spicer’s poetry in the late 1960s he was already dead, but I had no real way of knowing that. Of all the poets in Donald Allen’s anthology, The New American Poetry—that overwhelming, simultaneously revealed crowd that included Olson, Duncan, O’Hara, Ashbery, Jones, Snyder, Creeley, and so many others—he was the one who did “not like his life written down” but who could be contacted at “The Place.” (I didn’t know that was an artists’ bar in San Francisco; it just sounded like the kind of spot, in the world but not of it, that everyone was hoping to find.) He was the one who had written “Imaginary Elegies,” a poem (or the start of a sequence of poems) utterly different in tone from anything else in the anthology. It sounded like something imparted by the ghost of Hölderlin—“Poetry, almost blind like a camera / Is alive in sight only for a second”—but in a language that could be plain and American enough to provide the basis for a slightly off-center surfing record: “When I praise the sun or any bronze god derived from it / Don’t think I wouldn’t rather praise the very tall blond boy / Who ate all of my potato-chips at the Red Lizard.” It was as otherworldly as a translation of some newly discovered shamanic hymn, and as shiny and clankingly concrete as a kitchen drawer full of spoons: “The moon is God’s big yellow eye remembering / What we have lost or never thought. That’s why / The moon looks raw and ghostly in the dark.”

Before too long I learned that Spicer had died in San Francisco in 1965, of alcoholism, and I began to read more of his work—as much, that is, as could be found. His poetry had been published by small Bay Area presses when it had been published at all, and continued to circulate in hard-to-find chapbooks and doubtful pirated editions. Not until the publication in 1975 of The Collected Books of Jack Spicer, edited by Robin Blaser, did the major part of it become generally available. But there was much more writing still to emerge—other poems, manifestos, handbills, questionnaires, letters, novels, plays, and the elusive “Vancouver lectures”—which, even in incomplete form, had established themselves as an indispensable text for young poets. (The idea that writing poetry was a matter of taking dictation from unseen Martians seemed to make a good deal more sense than the theories of Allen Tate or Cleanth Brooks.) The lectures were finally published in 1998 as The House That Jack Built, edited by Peter Gizzi, the same year that Lewis Ellingham and Kevin Killian published the indispensable biography Poet Be Like God: Jack Spicer and the San Francisco Renaissance.

Now—43 years after Spicer’s death, a longer period than his lifespan—Gizzi and Killian have joined to give us a comprehensive gathering of Spicer’s poetry, My Vocabulary Did This to Me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer. The book offers a great deal of work previously published either marginally or not at all (including a number of serial poems that didn’t make it into The Collected Books), and establishes Spicer as one of the distinct voices of the mid-20th century, beautiful and troubling, weirdly and bitterly funny, and memorable as few poets are. To come back to this work is to realize how tenaciously Spicer’s phrases cling to the mind, whether as bursts of startling clarity or nagging unresolved fragments. To absorb his work early on was to need, at some later point, to be delivered from it, to clear the way for alternative incoming radio signals, even if the only way to do that was to burrow ever deeper into those opaque sentences as if looking for an exit: “They expect everybody to be insane. / This is a poem about the death of John F. Kennedy. . . . Death is not final. Only parking lots.” When, in his epoch-making Language Spicer wrote, "The ground still squirming. The ground still not fixed as I thought it would be in an adult world." he might have been describing the way his own work refuses to settle down into a framed image.

Tags:

No comments:

Post a Comment