At the bottom, there is also a definition of the amygdala hijack, a term coined by Daniel Goleman.

When the amygdala takes over, we become our fear. Making that fear an object of awareness is one way to break that fear trance.

The Machinery of Upset

posted on: August 4th, 2014

(Emotional) life is great when we feel enthusiastic, contented, peaceful, happy, interested, loving, etc. But when we’re upset, or aroused to go looking for trouble, life ain’t so great.

To address this problem, let’s turn to a strategy used widely in science (and Buddhism, interestingly): analyze things into their fundamental elements, such as the quarks and other subatomic particles that form an atom or the Five Aggregates in Buddhism of form, feeling (the “hedonic tone” of experience as pleasant-neutral-unpleasant), perception, volitional formations, and consciousness.

We’ll apply that strategy to the machinery of getting upset. Here is a summary of the eight major “gears” of that machine – somewhat based on how they unfold in time, though they actually often happen in circular or simultaneous ways, intertwining with and co-determining each other.

The point of this close analysis, this deconstruction, is not intellectual understanding or theory, but increasing your own mindfulness into your experience, and creating more points of intervention within it to reduce the suffering you cause for yourself – and other people.

This will be more real for you if you first imagine a recent upset or two, and replay it in your mind in slow motion.

Appraisals

Self-Referencing

- What do we focus on, what do we pick out of the larger mosaic?

- What meaning do we give the event? How do we frame it?

- How significant do we make it? (Is it a 2 on the Ugh scale . . . Or a 10?)

- What intentions do we attribute to others?

- What are the embedded beliefs about other people? The world? The past? The future?

- In sum, what views are we attached to? -> Mainly frontal lobe and language circuits of left temporal lobe.

Vulnerabilities

- Upsets arise within the perspective of “I.”

- What is the sense of “I” that is running at the time? Strong? Weak? Mistreated?

- Are you taking things personally?

- How does the sense of self change over the course of the upset (often intensifying)? -> Circuits of “self” are distributed throughout the brain.

Memory

- We all have vulnerabilities, which challenges penetrate through and/or get amplified by (moderated by inner and outer resources).

- Physiological: Pain, fatigue, hunger, lack of sleep, biochemical imbalances, illness.

- Temperamental: Anxious, rigid, angry, melancholic, spirited/ADHD.

- Psychological: Personality, culture, effects of gender, race, sexual orientation, etc. -> Depending on its nature, a vulnerability can be embodied or represented in many ways.

Aversion

- Stimuli are interpreted in terms of episodic memories of similar experiences.

- And in terms of implicit, emotional memories or other, unconscious associations. (Especially trauma)

- These shade, distort, and amplify stimuli, packaging them with “spin” and sending them off to the rest of the brain. -> Hippocampus, with other memory circuits.

Bodily Activation

- The feeling tone of “unpleasant” is in full swing at this point, though present in the previous “gears” of survival reactivity.

- In primitive organisms – and thus the primitive circuits of our own brain – the unpleasant/ aversion circuit is more primary than the pleasant/approach circuit since aversion often calls for all the animal’s resources and approaching does not.

- Aversion can also be a temperamental tendency.

- The Buddha paid much attention to aversion – such as to ill will – in his teachings, because it is so fundamental, and such a source of suffering. -> Involves the limbic system, especially the amygdala.

Negative Emotions

- The body energizes to respond; getting upset activates the stress machinery just like getting chased by a lion.

- Sympathetic nervous system (fight-or-flight).

- Hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.

- All this triggers blood to the large muscles (hit or run), dilates pupils (see better in darkness), cascades cortisol and adrenaline, increases heart rate, etc.

- These systems activate quickly, but their effects fade away slowly.

- There is much collateral damage in the body and mind from chronically “going to war.”

Loss of Executive Control

- Emotions are a fantastic evolutionary achievement for promoting grandchildren.

- Both the prosocial bonding emotions of caring, compassion, love, sympathetic joy . . .

- And the fight-or-flight emotions of fear, anger, sorrow, shame.

- Emotions organize, mobilize the whole brain.

- They also shade our perceptions and thoughts in self-reinforcing ways.

- The survival machine is designed to make you identify yourself with your body and your emotional reactions. That identification is highly motivating for keeping yourself alive!

- So, in an upset, there is typically a loss of “observing ego” detachment, and instead a kind of emotional hijacking – all facilitated by neural circuits in which amygdala-shaped information gets fast-tracked throughout the brain, ahead of slower frontal lobe interpretations.

- With maturation (sometimes into the mid-twenties) and with experience, the frontal (especially prefrontal) cortices can comment on and direct emotional reactions more effectively.

* * * * *

Emotional Hijacking

posted on: September 1st, 2014

In light of the machinery of survival-based, emotional reactivity, let’s look more narrowly at what Daniel Goleman has called “emotional hijacking.”

The emotional circuits of your brain – which are relatively primitive from an evolutionary standpoint, originally developed when dinosaurs ruled the earth – exert great influence over the more modern layers of the brain in the cerebral cortex. They do this in large part by continually “packaging” incoming sensory information in two hugely influential ways:

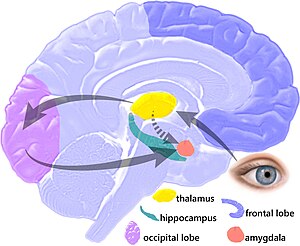

- Labeling it with a subjective feeling tone: pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral. This is primarily accomplished by the amygdala, in close concert with the hippocampus; this circuit is probably the specific structure of the brain responsible for the feeling aggregate in Buddhism (and one of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness).

- Ordering a fundamental behavioral response: approach, avoid, or ignore. The amygdala-hippocampus duo keep answering the two questions an organism – you and I – continually faces in its environment: Is it OK or not? And what should I do?

Meanwhile, the frontal lobes have also been receiving and processing sensory information. But much of it went through the amygdala first, especially if it was emotionally charged, including linked to past memories of threat or pain or trauma. Studies have shown that differences in amygdala activation probably account for much of the variation, among people, in emotional temperaments and reactions to negative information.

The amygdala sends its interpretations of stimuli – with its own “spin” added – throughout the brain, including to the frontal lobes. In particular, it sends its signals directly to the brain stem without processing by the frontal lobes – to trigger autonomic (fight or flight) and behavioral responses. And those patterns of activation in turn ripple back up to the frontal lobes, also affecting its interpretations of events and its plans for what to do.

It’s like there is a poorly controlled, emotionally reactive, not very bright, paranoid, and trigger-happy lieutenant in the control room of a missile silo watching radar screens and judging what he sees. Headquarters is a hundred miles away, also seeing the same screens — but (A) it gets its information after the lieutenant does, (B) the lieutenant’s judgments affect what shows upon the screens at headquarters, and (C) his instructions to “launch” get to the missiles seconds before headquarters can signal “stand down!”

* * * * *

Here is a definition of the "amygdala hijack" that Daniel Goleman outlined in his seminal book, Emotional Intelligence.

Amygdala hijack

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Amygdala hijack is a term coined by Daniel Goleman in his 1996 book Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ.[1] Drawing on the work of Joseph E. LeDoux, Goleman uses the term to describe emotional responses from people which are immediate and overwhelming, and out of measure with the actual stimulus because it has triggered a much more significant emotional threat.[2]

Definition

From the thalamus, a part of the stimulus goes directly to the amygdala while another part is sent to the neocortex or "thinking brain". If the amygdala perceives a match to the stimulus, i.e., if the record of experiences in the hippocampus tells the amygdala that it is a fight, flight or freeze situation, then the amygdala triggers the HPA (hypothalmic-pituitary-adrenal) axis and hijacks the rational brain. This emotional brain activity processes information milliseconds earlier than the rational brain, so in case of a match, the amygdala acts before any possible direction from the neocortex can be received. If, however, the amygdala does not find any match to the stimulus received with its recorded threatening situations, then it acts according to the directions received from the neo-cortex. When the amygdala perceives a threat, it can lead that person to react irrationally and destructively.[3]

Goleman states that "[e]motions make us pay attention right now — this is urgent - and gives us an immediate action plan without having to think twice. The emotional component evolved very early: Do I eat it, or does it eat me?" The emotional response "can take over the rest of the brain in a millisecond if threatened."[4][5] An amygdala hijack exhibits three signs: strong emotional reaction, sudden onset, and post-episode realization if the reaction was inappropriate.[4]

Goleman later emphasised that "self-control is crucial ...when facing someone who is in the throes of an amygdala hijack"[6] so as to avoid a complementary hijacking - whether in work situations, or in private life. Thus for example 'one key marital competence is for partners to learn to soothe their own distressed feelings...nothing gets resolved positively when husband or wife is in the midst of an emotional hijacking.'[7] The danger is that "when our partner becomes, in effect, our enemy, we are in the grip of an 'amygdala hijack' in which our emotional memory, lodged in the limbic center of our brain, rules our reactions without the benefit of logic or reason...which causes our bodies to go into a 'fight or flight' response."[8]

Positive hijacks

Goleman points out that "'not all limbic hijackings are distressing. When a joke strikes someone as so uproarious that their laughter is almost explosive, that, too, is a limbic response. It is at work also in moments of intense joy."[9]

He also cites the case of a man strolling by a canal when he saw a girl staring petrified at the water. "[B]efore he knew quite why, he had jumped into the water — in his coat and tie. Only once he was in the water did he realize that the girl was staring in shock at a toddler who had fallen in — whom he was able to rescue."[10]

Emotional relearning

LeDoux was positive about the possibility of learning to control the amygdala's hair-trigger role in emotional outbursts. "Once your emotional system learns something, it seems you never let it go. What therapy does is teach you how to control it — it teaches your neocortex how to inhibit your amygdala. The propensity to act is suppressed, while your basic emotion about it remains in a subdued form."[11]

References

- Nadler, Relly. "What Was I Thinking? Handling the Hijack". Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- "Conflict and Your Brain aka "The Amygdala Hijacking"". Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- Freedman, Joshua. "Hijacking of the Amygdala". Retrieved 2010-04-06.[dead link]

- Horowitz, Shell. "Emotional Intelligence - Stop Amygdala Hijackings". Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- Hughes, Dennis. "Interview with Daniel Goleman". Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- Daniel Goleman, Working with Emotional Intelligence (1999) p. 87

- Goleman, Emotional Intelligence p. 144

- Rita DeMaria et al., Building Intimate Relationships (2003) p. 57

- Goleman, Emotional Intelligence p. 14

- Goleman, Emotional Intelligence p. 17

- Goleman, Emotional Intelligence p. 213

No comments:

Post a Comment