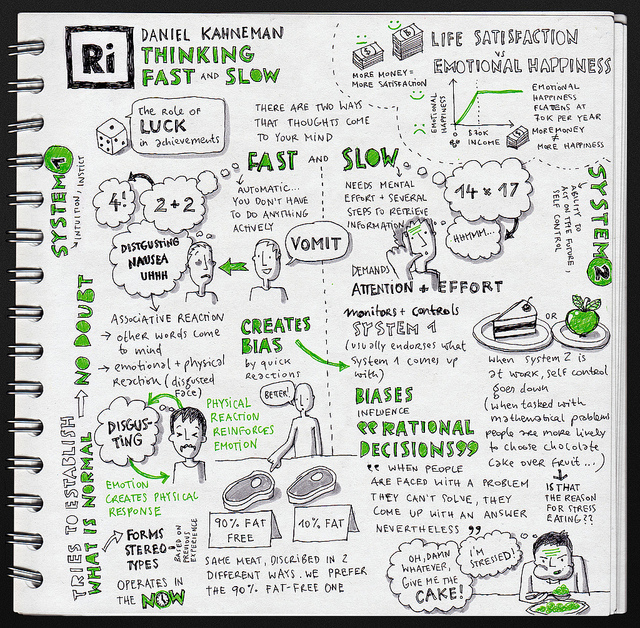

Wonderful tribute to a pioneer and original thinker. Daniel Kahneman, author of Thinking Fast and Slow, one of the best books I have read in recent years - forced me to change some of the things I thought to be true about the mind, and it confirmed things I had intuited to be true.

ON KAHNEMAN

A Reality Club Discussion on the Work of Daniel Kahneman [3.27.14]

Introduction By: John Brockman

HOW HAS KAHNEMAN'S WORK INFLUENCED YOUR OWN?

WHAT STEP DID IT MAKE POSSIBLE?

THE REALITY CLUB: Michael McCullough, June Gruber & Amy Cuddy, Xavier Gabaix & David Laibson, Gary Marcus, Christopher Chabris, Nicholas Epley, Jennifer Jacquet, Laurie Santos & Tamar Gendler, Jason Zweig, Mahzarin Banaji, Fiery Cushman, William Poundstone, Andrew Rosenfield, Cass Sunstein, Phil Rosenzweig, Richard Nisbett, Richard Thaler & Sendhil Mullainathan, Eric Kandel, Michael Norton, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Joshua Greene, Walter Mischel, Steven Pinker, Nicholas Christakis, Rory Sutherland

Introduction

Daniel Kahneman turned 80 on March 5th and Edge noted the occasion with a reprise of a number of his contributions to our pages. (See "Kahneman Turns 80").

At that time, Kahneman's longtime colleague, behavioural economist Richard Thaler, suggested that Edge follow up the birthday announcement by doing what it does best, asking Edgies who work in fields including, but not limited to, psychology, cognitive science, behavioral economics, law, medicine, a question.

For their responses to Thaler's question—"How has Kahneman's work influenced your own? What step did it make possible?"—we asked a selected group of Edgeis to include inspired leaps off of Kahneman's shoulders, not just applications of his ideas. We used a comment made by research psychologist Steven Pinker in the Q&A following Kahneman's talk at the 2011 Edge Master Class, as an example. Pinker said:

"If somebody were to ask me what are the most important contributions to human life from psychology, I would identify this work [by Kahneman & Tversky] as maybe number one, and certainly in the top two or three. In fact, I would identify the work on reasoning as one of the most important things that we've learned about anywhere. When we were trying to identify what any educated person should know in the entire expanse of knowledge, I argued unsuccessfully that the work on human cognition and probabilistic reason should be up there as one of the first things any educated person should know."One way to consider the long and illustrious career of a great thinker such as Kahneman is not as a summation, but as a commission, one that gives us permission to move forward in certain ways. (Think Newton's "If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.") As social psychologist Richard Nisbett noted, "It's not just a celebration of Danny. It's a celebration of behavioral science.".

—John Brockman

DANIEL KAHNEMAN is the recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economics, 2002 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom, 2013. He is Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology Emeritus, Princeton, and author of Thinking Fast and Slow.

Reality Club Discussion

Michael McCullough

Director, Evolution and Human Behavior Laboratory, Professor of Psychology, Cooper Fellow, University of Miami; Author, Beyond Revenge: The Evolution of the Forgiveness Instinct

Rats Pay to Run; Humans Pay for Revenge

I got my introduction to Daniel Kahneman's ideas in the late 1980s while I was still an undergraduate. His name and his ideas just kept coming up, semester after semester, in course after course. Even a second- or third-year psychology student (assuming he or she had been paying adequate attention) could tell: This Kahneman person was a psychologist whose ideas mattered.

Some years later, I would turn to Kahneman's earlier research on the so-called Ultimatum Game for insights into the human appetite for revenge. In the Ultimatum Game, some amount of money, say $10, is to be divided between two players who are completely anonymous to each other. One player—the proposer—proposes a split, and the other player—the Responder—can either accept the proposal (and receive the portion of the $10 stake that that Proposer offered) or reject the proposal, in which case both players receive nothing.

Standard rational-actor models of economic behavior, of course, depict humans as income maximizers. This depiction leads one to expect Proposers to offer very small amounts to Responders, and to expect Responders to accept all non-zero offers. But that's not how Kahneman's experiment turned out. Instead, what Kahneman (along with his co-authors Jack Knetsch and Richard Thaler) found was that Proposers typically offered about $4.50 to their responders—a result that has since been replicated in scores of experiments. Proposers don't behave like rational actors should. They behave like creatures that are balancing a love of income with some other sort of concern.

That other concern, it seems, is the conviction that their Responders will rebuke them for unfair treatment—a concern that turns out to be a well-founded one. Kahneman and colleagues found that the typical Responder was willing to refuse offers that would net them less than $2.25 or so. Far from behaving like Homo economicus was expected to behave (which is to say, accepting any non-zero offer), Kahneman's Responders were willing to scuttle deals that revealed that their Proposers did not possess proper regard for their welfare. Responders' behavior is not merely governed by a love of money; it's also governed by a love of proper treatment from one's social partners.

A rat is a kind of animal that will pay for the opportunity to run on a wheel. A human is a kind of animal that will pay for the opportunity to revenge poor treatment at the hands of a stranger. Humans love respect, and humans love revenge, the way lab rats love to run. Any model of human behavior that ignores loves like these, Kahneman's results showed me, is a model that is going to fall short in profound ways.

_____

June Gruber Assistant Professor of Psychology, Yale University

Amy J.C. Cuddy Associate Professor of Business Administration, Hellman Faculty Fellow, Harvard Business School

Daniel Kahneman is undoubtedly one of the most astounding minds in our field. His influence is equally vast and far-reaching as it is deep and sound. Yet his influence stretches beyond even science itself to cultivate two essential qualities in the humans behind the science: humility and receptiveness.

For humility, Einstein couldn't have said it better: "A true genius admits that he/she knows nothing." Kahneman's approach to science and interacting with others was one of great knowledge, yet emphasizing instead what he didn't know. Take his contributions to the study of happiness and well-being. As someone who pioneered our understanding of the nature of happiness—from what we mean by happiness, to overestimating the weight of factors such as geography that determine our happiness, to our two competing selves in searching for happiness—he once said that he "did not understand what happiness was." He emphasized how complex happiness was, how much we have yet to understand. Not once did he brag about his own work or insights, or make simplified sound-bite statements about happiness that often plague the field. Instead, he created a common ground where scientists could stand in the face of the unknown, and that happiness was one of these great unknowns sitting right in front of is. Part of his rich understanding of happiness and well-being is his noting what he didn't know and that we are very small in the vast space of knowing things.

For receptiveness, Kahneman is both an advocate for, and model of, civilized discourse in scientific debate. Cultivating respectful and productive approaches to resolving scientific disagreements is so important to him that he has named it as perhaps the most important legacy he hopes to leave. His work on adversarial collaboration offers one route through which scholars who disagree on a particular theoretical issue might attempt to resolve their dispute —by first identifying what they agree on, and then trying to "trade" the differences. But his contribution here goes far beyond the formal construct of adversarial collaboration. He continues to be guided by this principle, encouraging scholars who disagree about ideas to do so in a way that is respectful and productive. This is not an easy stance to take. In fact, psychological science shows us that it's actually quite difficult to be gracious and dignified when your ideas (or you) are being attacked. It's much easier to give in—to quickly fire back which serves neither the scholars nor the science. "You have to be willing to not win," he said. It sounds so simple—like advice we might give to our kids. But it is not easy, even for scientists with the best intentions, to live by that advice. Nonetheless, he does.

_____

Xavier Gabaix Martin J. Gruber Professor of Finance, New York University

David Laibson Robert I. Goldman Professor of Economics, Harvard University

Danny Kahneman's work opened myriad doors for us. Most importantly, his work with Amos Tversky in the 1970's broke the conceptual monopoly of classical economic theory. By identifying and convincingly documenting robust empirical deviations from classical predictions, Danny and Amos created intellectual space for a new generation of young scholars who wanted to explore alternatives to the rational actor model. Danny made it respectable to question classical axioms. We've both taught almost every one of Danny's papers and read them each many times.

When Thinking Fast and Slow was published, we expected not to learn much that we hadn't learned already. We were wrong. His book is a master class, which speaks to students with every level of preparation. It inspired us to form a two-person reading group that met weekly for a year to discuss every page of the book. With Danny as our tour guide, we revisited many of the original papers with a synthetic perspective. His book has prompted a new research program for us as well. After all these years, Danny keeps surprising and inspiring us.

_____

Gary Marcus

Cognitive Scientist; Author, Guitar Zero: The New Musician and the Science of Learning

More than a hundred years into the modern history of psychology, I think it's fair to say that we are still a long way from fully understanding how the mind works. But it's also fair to say that nobody will come up with a compelling account of human cognition unless they wrestle seriously with Daniel Kahneman's pioneering work with Amos Tversky on heuristics and cognitive biases.

You would think that point would be obvious, but in my view, none of the currently fashionable theories of mind take Kahneman and Tversky's work seriously enough. Take, for instance, the popular notion that the mind might be a Bayesian engine of probabilistic cognition. According to one leading theorist, "over the past decade, many aspects of higher-level cognition have been illuminated by the mathematics of Bayesian statistics." Demonstration after demonstration purports to show that in certain narrowly-defined tasks, human psychology follows directly from the laws of probability. In this domain or that, people are said to make "optimal" or "near-optimal" decisions. People, for example, are very good at extrapolating how long someone might remain in the Senate, given that Senator X has already been there for a decade. But Bayesian zealots seem to forget just how lousy human beings are in other cases of extrapolation, as Kahneman and Tversky showed long ago, with their framing effect. (Take a dollar bill from your pocket, read the last three digits of the serial number, and then guess when Attila the Hun was born; most people will erroneously extrapolate from this bit of wholly irrelevant information.) In a recent review, I suggested that every alleged Bayesian success could be juxtaposed with an equally compelling cognitive error, most of which were first documented by Kahneman and Tversky. Every time I read the Bayesian literature, I wince, and think of a different cognitive error: confirmation bias. It's easy to find evidence for any old theory; good science requires considering evidence that might potentially go against one's theory. In my humble opinion, anyone who tries to understand the mind without taking seriously Kahneman's oeuvre is doomed to failure.

In my own work, I have thought deeply about what Kahneman's work might mean for evolutionary psychology. The default assumption of evolutionary psychology is one of optimality: give evolution enough time, and eventually it will alight on a beautiful, elegant solution, like the retina, sensitive to a single photon of light. The reality of evolution is that it is a blind process, with no guarantee of alighting on optimality. Too much of evolutionary psychology, in my view, dwells on systems in which the mind is apparently optimal; the real challenge ought to be in understanding how those apparently-optimal systems live alongside other systems that sometimes confoundingly seem to do the wrong thing; until evolutionary psychology can explain anchoring, availability, and future discounting, as well as it can explain mate selection and reciprocal altruism; it will be only half a science. The ultimate goal of human psychology must be to characterize both what we do well, and what we do poorly, and how we balance the two. Kahneman and Tversky's work is, without question, the best place to start.

_____

Christopher Chabris

Associate Professor of Psychology, Union College; Co-author, The Invisible Gorilla, and Other Ways Our Intuitions Deceive Us.

There's an overarching lesson I have learned from the work of Danny Kahneman, Amos Tversky, and their colleagues who collectively pioneered the modern study of judgment and decision-making: Don't trust your intuition. It's such an important lesson that it wound up in the subtitle of my book. So I am wary of consulting my intuition to try to discern a pattern of influence that may only be visible through the distorting lens of hindsight. Instead, I'll talk about the value of Kahneman's approach to behavioral research.

As I see it, the Kahneman formula for high-impact social science combines three elements:

1. Systematic human error: Kahneman and Tversky are known for discovering situations where many or most people give answers that are inconsistent with some normative theory of what is correct. Usually this theory is based on logic or basic probability or arithmetic. But those errors aren't random—they are systematic errors, also known as biases. It's easy to forget how revolutionary this approach once was. Much research in cognitive psychology compares the rate of error in different conditions, but it doesn't look at the content of those errors. Looking at the frequency of mistakes across different conditions is a perfectly valid and useful research strategy, but looking at systematic error is more powerful. For one thing, when a normative theory makes a strong prediction—that a certain answer is simply wrong and should never occur—then it is easier to find large effects. (The t-test against a theoretical value is a high-power statistical procedure.)Combining these three elements isn't the only way to do good behavioral research, by any means. And of course it doesn't automatically work. It can be dangerously seductive if it leads us to pursue what is surprising or newsworthy over what is important and true. But it has the potential to point toward deeply nonobvious facts that have large consequences. Kahneman and his colleagues discovered lots of those, including the conjunction fallacy, the neglect of base rates, the excessive pain of losses as compared to the pleasure of gains, the difference in how we value things we own and things we don't, and the surprising happiness of people who have suffered greatly. We can and should discuss whether these are all really errors (as opposed to behaviors that have or had adaptive value) and we should work on discovering the mechanisms that lie beneath them. Those pursuits are likely to bear fruit precisely because they are starting from the firm foundation Kahneman's approach established.

2. Large effects: There's nothing wrong with looking for small effects, and small effects can have great theoretical meaning. But they are harder to find, and they tend to be of less practical importance. As much as possible we should work on large effects that can be easily replicated, since those will provide a firm empirical foundation for future work. If some researchers can obtain effects that others can't, progress will be difficult. Kahneman's work shows us that there are many large effects out there to be found and understood.

3. Simple experiments: The simpler an experiment is to conduct, the more likely it is that multiple independent researchers will be able to replicate it, extend it, and exchange information about it. Kahneman's most influential studies consisted of asking research subjects just one easily-understood question, and the methodology was the simple randomized experiment.

_____

Nicholas Epley Professor of Behavioral Science, University of Chicago, Booth School of Business

Essential Ingredients

Kahneman's influence was to provide the essential ingredients for all of my work: a problem, and possible solutions. The problem was that people's beliefs, judgments, and choices are routinely "wrong." They may wrong because they disagree with a statistical principle, a rational principle, reality, or some combination of all three. The solution is that people beliefs, judgments, and choices are not guided simply by statistics, rationality, or reality, but instead are guided by generally intelligent, but imperfect, psychological processes that take hard problems and convert them to easy problems that normal human beings can solve. If you understand these processes that guide intuitive judgment, then you can understand why perception and reality diverge.

By extending Kahneman's problem as well as his ideas about its solution, I have built a career trying to understand how otherwise brilliant human beings can be so routinely "wrong" in their beliefs and judgments about each other. Why do people overestimate how often others agree with them? Why are people sometimes less accurate predicting their own future behavior than predicting others' behavior? Why do people overestimate how harshly they will be judged for an embarrassing blunder? Why do liberals think conservatives have more extreme views than conservatives actually do? The list of such cases where our social thinking goes wrong is long, but it is Kahneman's influence that runs through its entire length.

Asking how Kahneman's work has influenced my own is a bit like asking a doctor how oxygen influences life. My work wouldn't exist without him.

_____

Jennifer Jacquet

Clinical Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies, NYU; Researching cooperation and the tragedy of the commons

When I was a 20-year-old undergraduate majoring in economics I heard Jack Knetsch, a longtime Kahneman collaborator, speak about the endowment effect. The talk was a revelation and introduced me to the experimental side of decision-making, where I then found work by Daniel Kahneman and others, who had been studying decision-making for decades. As professors were trying to convince me of behavior based on laws of supply and demand, the insights of Kahneman, Tversky, Knetsch, Thaler and others showed that the conventional economic models were deeply flawed.

After what I see as years of hard work, experiments of admirable design, lucid writing, and quiet leadership, Kahneman, a man who spent the majority of his career in departments of psychology, earned the highest prize in economics. This was a reminder that some of the best insights into economic behavior could be (and had been) gleaned outside of the discipline. Aside from amassing such a huge and influential body of work, Kahneman's revolutionary advances in economic decision-making granted everyone permission to take scholars outside the field of economics seriously and reminded us that humans who think both fast and slow, not mathematical models built on ideologies, are the bedrock of behavior.

_____

Laurie R. Santos

Associate Professor of Psychology, Director, Comparative Cognition Laboratory, Yale University

Tamar Gendler

Professor of Philosophy and Cognitive Science, and Chair, Department of Philosophy; Deputy Provost for Humanities and Initiatives, Yale University

Ralph Waldo Emerson once noted that "in every work of genius we recognize our own rejected thoughts: they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty."

We've all at some point had the thought "I'm feeling pulled in two directions." For example, we all know what it feels like to desire some immediate gratification while recognizing that it would be better in the long run to resist. Thoughts like these are noticed even early in life: very young children also notice the conflict between different "sides" of themselves. But our thoughts about this conflict are often left inchoate, or even rejected.

It took somebody with Danny Kahneman's genius to live up to Emerson's challenge: to give these kinds of thoughts their appropriate majesty.

What Danny showed the world is that our conflicting cognitive moments fit into a pattern: they are all the result of a fundamental feature of our cognitive architecture, namely, that our minds are dualistic. Danny's ingenious studies gave us insight into the processes that make us more than just our System IIs. While he wasn't the first to notice that the fast systems existed, he was the first to give us tools that could tap into the mechanisms that underlie our automatic heuristics.

And what Danny showed the world, he has also taught to the two of us as scholars. Even though we work on superficially different topics (the evolutionary origins of cognitive biases in other primates and the philosophical roots of the relation between rational and arational processing—respectively) in two different departments (Psychology and Philosophy), Danny's influence on both of our research programs has been profound. His work has defined the space in which our questions emerge.

But Danny's work has also left both our research programs with a new challenge. Novices who hear about Danny's findings for the first time sometimes get the wrong message about thinking fast or slow—they want to choose one or the other. But this misses the important point. Danny's work teaches us that we don't need to make that choice: An effective mind is one that doesn't fall prey to the easy answers it gets from System I when they mislead, but leaves the fast heuristics in charge when they're best suited to steer us in the right direction. We now know that our goal shouldn't be to get rid of one system or the other, but to get them both into an appropriate balance.

The problem is how to do this—what is the right balance and how do we achieve it? There's still a lot to learn, both in terms of mechanisms and in terms of applications. Answering this new question is the task of the generation that Danny has inspired.

_____

Jason Zweig

Journalist; Personal Finance Columnist, The Wall Street Journal; Author, Your Money and Your Brain

While I worked with Danny on a project, many things amazed me about this man whom I had believed I already knew well: his inexhaustible mental energy, his complete comfort in saying "I don't know," his ability to wield a softly spoken "Why?" like the swipe of a giant halberd that could cleave overconfidence with a single blow.

But nothing amazed me more about Danny than his ability to detonate what we had just done.

Anyone who has ever collaborated with him tells a version of this story: You go to sleep feeling that Danny and you had done important and incontestably good work that day. You wake up at a normal human hour, grab breakfast, and open your email. To your consternation, you see a string of emails from Danny, beginning around 2:30 a.m. The subject lines commence in worry, turn darker, and end around 5 a.m. expressing complete doubt about the previous day's work.

You send an email asking when he can talk; you assume Danny must be asleep after staying up all night trashing the chapter. Your cellphone rings a few seconds later. "I think I figured out the problem," says Danny, sounding remarkably chipper. "What do you think of this approach instead?"

The next thing you know, he sends a version so utterly transformed that it is unrecognizable: It begins differently, it ends differently, it incorporates anecdotes and evidence you never would have thought of, it draws on research that you've never heard of. If the earlier version was close to gold, this one is hewn out of something like diamond: The raw materials have all changed, but the same ideas are somehow illuminated with a sharper shift of brilliance.

The first time this happened, I was thunderstruck. How did he do that? How could anybody do that? When I asked Danny how he could start again as if we had never written an earlier draft, he said the words I've never forgotten: "I have no sunk costs."

To most people, rewriting is an act of cosmetology: You nip, you tuck, you slather on lipstick. To Danny, rewriting is an act of war: If something needs to be rewritten then it needs to be destroyed. The enemy in that war is yourself.

After decades of trying, I still hadn't learned how to be a writer until I worked with Danny.

I no longer try to fix what I've just written if it doesn't work. I try to destroy it instead— and start all over as if I had never written a word.

Danny taught me that you can never create something worth reading unless you are committed to the total destruction of everything that isn't. He taught me to have no sunk costs.

_____

Mahzarin Banaji

Psychologist; Richard Clarke Cabot Professor of Social Ethics, Department of Psychology, Harvard University; Co-author, Blind Spot: Hidden Biases of Good People

I first encountered Danny Kahneman and Amos Tversky's work in a psychology course I took in India. I can't say that I had the sophistication to appreciate it or the foresight to recognize its importance until later when I read the work of Herbert Simon and Allen Newell in the early 1980s, and spotted the deep level similarity—in spite of the difference in orientations.

I was fortunate to be surrounded by people who always saw the wonder of Kahneman and Tversky's work, so I don't recall having to defend it against criticisms. The bounds on rationality that some K&T heuristics created, when applied to decisions about groups of people, may be called stereotypes or intergroup attitudes. The bounds on rationality shown by Kahneman seemed akin to me to the bounds on rationality placed on our thinking by the social categories to which we belong, at the most simple level, the categories of "us" and "them". And so when I began to think about particular errors in social cognition, for example those that create automatic association of "good" and "bad" with racial or ethnic groups (in the absence of similar sentiments in conscious self report), it seemed to me that the path along which I was to proceed was going to be easy, having been cleared by Danny and Amos among others. All we were doing is showing the bounds on thinking that had some moral or ethical aspects.

It seemed rather obvious that the rules of thumb that described thinking in general encompassed the social world as well. And the evidence did show that reliance on gender, race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, age, nationality, religion, and dozens of other categories into which humans are placed could produce similar corruptions in computation and decision-making as K&T had shown about thinking in general.

So it was a surprise when we first reported some results to encounter resistance to the idea that automatic stereotypes existed or that they were ordinary enough to characterize all human minds (including those of the scientists who studied them). In these moments, Danny's work could always be relied upon as a model for discovery; that the task was to discover the nature of human minds, irrespective of whether the results painted an appealing view of ourselves or not. Why it is that the legitimacy of some errors and heuristics is fully accepted, but particular social instantiations of the same is resisted has always been of some mild interest to me.

_____

Fiery Cushman

Assistant Professor, Cognitive, Linguistic and Psychological Sciences, Brown University

I appreciated Kahneman's accomplishments for a long time in the strict cognitive sense in which I once knew that the Vatican is in Rome and they've got some awfully good art there. But it was only quite recently that I was made to really feel the full scope of his accomplishments; to be gobsmacked in the way it felt to first see that Italian art from below. And it happened at an Edge event*, of all places.

Several younger social scientists were brought together and asked to discuss whatever they considered to be the most exciting new developments in their field. The first speaker talked about "big data", but the specific case study at the heart of his talk involved a reanalysis of loss aversion. Kahneman joined the event as a discussant, and of course we were all keen to hear his perspective. The second speaker talked about the science of happiness; again, everyone glanced at Kahneman to gauge his reaction. The third speaker described some recent work hinting at the neural basis of dual process models. All eyes on Kahneman.

So here you had three young scientists selected more or less at random, each asked to talk about the thing that most excited them. Each chose a completely different topic. And Daniel Kahneman was not just foremost expert in the room on each of these topics, he was arguably the foremost expert in the world.

It is reasonable to wonder whether this is truly a credit to Kahneman, or instead an indictment of the imagination of a younger generation. This would be a fair critique if each the talks had simply reshuffled the basic ideas that Kahenman (and others of equal brilliance and foresight) had articulated many years ago. Fortunately, just the opposite was true: Each of the talks proposed challenges, corrections, and extensions of Kahneman's work.

How has that body work enabled my own? There is a saying that when you have a hammer everything looks like a nail. Psychologists have wielded hammers of every sort to model human reasoning—cognitivism, associationism, connectionism, analogy, logic, metaphor, heuristics, and so forth. What Kahneman made possible—in fact, inescapable—is the realization that mind is made of at least two kinds of things (nails and screws, perhaps?) and that they demand the application of very different tools. Because my own work is largely occupied with the problem of finding the right model for the mind's hardware, it is made immeasurably easier by knowing that there are at least two things I'm looking for.

In other words, to me, the most exciting thing happening in the social sciences right now is that we're finding ways to answer the questions that Kahneman's work defined .

* See Headcon '13: What's New In Social Science

_____

William Poundstone

Journalist; Author, Are Your Smart Enough To Work At Google?; Nominated twice for the Pulitzer Prize

As a writer of nonfiction I'm often in the position of trying to connect the dots—to draw grand conclusions from small samples. Do three events make a trend? Do three quoted sources justify a conclusion? Both are maxims of journalism. I try to keep in mind Kahneman and Tversky's Law of Small Numbers. It warns that small samples aren't nearly so informative, in our uncertain world, as intuition counsels. I have from time to time changed the wording of a passage with this in mind. If sources A, B, and C say that binge-viewing is changing the nature of television, it's fine to quote them, assuming the quotes are interesting, but there is little point in the writer repeating the claim as a "fact." For one thing, the reader will be all too quick to jump to that conclusion, without any pushing by the writer. For another, the community of experts may not be so unanimous as the sample (and/or the experts may be wrong).

The next edition of Strunk and White ought to have a Kahneman and Tversky rule: The writer should (usually) avoid supplying conclusions drawn from small samples.

_____

Andrew M. Rosenfield

Senior Lecturer in Law, U. Chicago Law School; Managing Partner, The Greatest Good (TGG).

I was educated at Chicago in the 1970s and never left. As Kahneman's work began to come to my attention in those days, it was not (then) received with great enthusiasm among most of my colleagues. How odd that seems to me now when it is universally admired everywhere, without qualification.

I met Danny quite late in his career—in the early 2000's, at a conference. That is the only conference that ever changed my life, and change my life it surely did.

His ideas seemed both completely clear, compelling and remarkably powerful. The only thing in my experience to which I can compare learning behavioral science from Danny is learning the mathematics of differential equations. As you start to understand differential equations, they first seem impossible, then magical and finally when you "get it" you see them as beautiful and remarkably general tools.

The broad and enduring value of the revolution Danny led, like all great new scientific thinking, will, of course, be greatest in application outside the academy.

We got to know one another and ended up in business together where for the last ten or so years we have helped to prove the efficacy of his work in many applications where doubters would have said (indeed did say) it would have no application. He proved them wrong.

_____

Cass R. Sunstein

Legal Scholar; Robert Walmsley University Professor, Harvard; Fmr, Administrator of White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs; Author, Why Nudge?

Danny Kahneman is responsible for so many ideas that one needs a heuristic to select among them. I am choosing the Coauthorship Heuristic.

From about 1996 until about 2007, I was privileged to work with Kahneman (and David Schkade) on a series of papers on punitive damage awards. Here are four ideas for which Kahneman is above all responsible. These ideas are hardly Kahneman’s most well-known, but they are full of implications, and we have only started to understand them.

1. The outrage heuristic. People’s judgments about punishment are a product of outrage, which operates as a shorthand for more complex inquiries that judges and lawyers often think relevant. When people decide about appropriate punishment, they tend to ask a simple question: How outrageous was the underlying conduct? It follows that people are intuitive retributivists, and also that utilitarian thinking will often seem uncongenial and even outrageous.We should be able to see the close connection between these findings and many themes in Kahneman’s work, and indeed the distinction between System 1 and System 2 helps to illuminate all of them. That distinction, and Kahneman’s findings about how risk-related intuitions can go wrong, very much influenced my work in the Obama Administration, where I was privileged to serve as the Administrator of the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. It is clear that in an increasing number of nations, public policy is a lot better than it would be because of Kahneman’s research. Both System 1 and System 2 concur: The influence of that research will grow significantly in the future.

2. Scaling without a modulus. Remarkably, it turns out that people often agree on how outrageous certain misconduct is (on a scale of 1 to 8), but also remarkably, their monetary judgments are all over the map. The reason is that people do not have a good sense of how to translate their judgments of outrage onto the monetary scale. As Kahneman shows, some work in psychophysics explains the problem: People are asked to “scale without a modulus,” and that is an exceedingly challenging task. The result is uncertainty and unpredictability. These claims have implications for numerous questions in law and policy, including the award of damages for pain and suffering, administrative penalties, and criminal sentences.

3. Rhetorical asymmetry. In our work on jury awards, we found that deliberating juries typically produce monetary awards against corporate defendants that are higher, and indeed much higher, than the median award of the individual jurors before deliberation began. Kahneman’s hypothesis is that in at least a certain category of cases, those who argue for higher awards have a rhetoric advantage over those who argue for lower awards, leading to a rhetorical asymmetry. The basic idea is that in light of social norms, one side, in certain debates, has an inherent advantage – and group judgments will shift accordingly. A similar rhetorical asymmetry can be found in groups of many kinds, in both private and public sectors, and it helps to explain why groups move.

4. Predictably incoherent judgments. We found that when people make moral or legal judgments in isolation, they produce a pattern of outcomes that they would themselves reject, if only they could see that pattern as a whole. A major reason is that human thinking is category-bound. When people see a case in isolation, they spontaneously compare it to other cases that are mainly drawn from the same category of harms. When people are required to compare cases that involve different kinds of harms, judgments that appear sensible when the problems are considered separately often appear incoherent and arbitrary in the broader context. In my view, Kahneman’s idea of predictable coherence has yet to be adequately appreciated; it bears on both fiscal policy and on regulation.

_____

Phil Rosenzweig

Professor of Strategy and International Business at IMD, Lausanne, Switzerland

For those of who studied economics at university, as I did in the 1970s, the work of Danny Kahneman and Amos Tversky came as a most welcome corrective. My first encounter with their work on heuristics and biases, while a doctoral student in the 1980s, was a transformational experience, a moment when the pieces of a larger puzzle are re-arranged and the world never looks quite the same again. The elegance of their experiments, honed and sharpened to capture precisely the phenomenon of interest, was such that even the field they challenged—economics—had to acknowledge the power of their findings. It's a rare duo that can so fundamentally call into question the received wisdom of a field and manage to get the results published in one of its leading journals, as was the case with their 1979 classic published in Econometrica, "Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk."

Even so, the application of many insights about judgment and choice, so neatly distilled in laboratory settings, has been neither a smooth nor straight road. The reason has less to do with shortcoming of the cognitive psychologists and decision theorists who conducted the studies, and more to do with the way others sought to generalize the findings without careful regard to the nature of real world decisions, which often involve circumstances that can be very different. Much of my research has been about precisely this: understanding the messy world of managerial decision making. For that, the research of Danny Kahneman has been an essential and firm foundation.

For years, there were (as the old saying has it) two kinds of people: those relatively few of us who were aware of the work of Danny Kahneman and Amos Tversky, and the much more numerous who were not. Happily, the balance is now shifting, and more of the general public has been able to hear directly a voice that is in equal measures wise and modest.

_____

Richard Nisbett

Professor of Psychology, University of Michigan; Author, Intelligence and How We Get It

Only people of a certain age will recall that when Danny and Amos began their work on heuristics, every social and behavioral scientist knew that their job was strictly empirical: you report only what people do and think. It was absolutely forbidden to be prescriptive—to say what people ought to do or think.

In light of this training, many people were outraged that Danny and Amos were making normative assertions about the way people should reason.

It's hard for most behavioral scientists to believe today that anyone, let alone a philosopher at a prominent institution, could have written in response to Danny's work that

"Ordinary human reasoning—by which I mean the reasoning of adults who have not been systematically educated in any branch of logic or probability theory—cannot be held to be faultily programmed: it sets its own standards."There are two main problems with this position.

This same philosopher—and many other philosophers and behavioral scientists as well—went on to try to show how Danny's reasoning about the problems he gave his subjects was wrong, and the reasoning of ordinary people was correct.

1) There is no such thing as ordinary untutored human reasoning: there is an enormous range of approaches to problems like the ones Danny presented to people. And that's just among people in developed countries who have had no special training. When you look at people in other cultures the range gets broader still.Early on in the debate, an article in Behavioral and Brain Science critiquing Danny's work was sent out to people who might reply to it. Surprisingly, almost no behavioral scientists took the side of the critics. And that was largely the end of it, except for a very few psychologists who continued the critique, often with a moralistic tone, and some psychologists who were ignorant of the details of the debate. Astonishingly, I've been told by a prominent philosopher that most philosophers still believe that "ordinary human reasoning" is without blemish and can't be criticized.

2) When you teach "ordinary" people rules like regression, the law of large numbers, and avoidance of the conjunction fallacy—either in classrooms or in laboratory settings—they don't give you static. They accept correction and try to reason in line with those rules. Danny's critics were placed in the position of a lawyer defending a client who had already thrown himself on the mercy of the court!

By far the greatest influence on my work was that of Amos and Danny. The research continues to guide my research and thinking.

I once saw a letter Danny wrote to an institution that was considering hiring one of the psychologists critical of his work. He wrote something to the effect that he expected to end up in the ashcan of intellectual history, but not at the hands of that particular psychologist. Danny was right about the latter, but not about the former. Intellectual history has been permanently deflected by his work.

_____

Richard H. Thaler

Father of Behavioral Economics; Director, Center for Decision Research, University of Chicago Graduate School of Business; Co-Author, Nudge

Sendhil Mullainathan

Professor of Economics, Harvard; Assistant Director for Research, The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), U.S. Treasury Department (2011-2013); Coauthor, Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much

Kahneman and Tversky made Behavioral Economics Adjacently Possible

Even in science, timing is everything. Charles Babbage' programmable computer was, in 1837, a step—or two—too early. Influential ideas are those that are novel but just familiar enough that existing researchers can build on them. Stuart Kauffman coined the term "adjacent possible" to describe the untapped potential that sits only one step away where scientists currently sit. Scientists who open the adjacent possible deserve the research equivalent of an "assist" in sports.

The earliest work of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, the famous "heuristics and biases program" merits many such assists, for opening up an important adjacent possible for economics: it made possible behavioral economics. We, like so many others, flowed into this territory and both owe our careers to the creation of that possibility.

Kahneman and Tversky's early work opened this door exactly because it was not what most people think it was. Many think of this work as an attack on rationality (often defined in some narrow technical sense). That misconception still exists among many, and it misses the entire point of their exercise. Attacks on rationality had been around well before Kahneman and Tversky—many people recognized that the simplifying assumptions of economics were grossly over-simplifying. Of course humans do not have infinite cognitive abilities. We are also not as strong as gorillas, as fast as cheetahs, and cannot swim like sea lions. But we do not therefore say that there is something wrong with humans. That we have limited cognitive abilities is both true and no more helpful to doing good social science that to acknowledge our weakness as swimmers. Pointing it out did it open any new doors.

Kahneman and Tversky's work did not just attack rationality, it offered a constructive alternative: a better description of how humans think. People, they argued, often use simple rules of thumb to make judgments, which incidentally is a pretty smart thing to do. But this is not the insight that left us one step from doing behavioral economics. The breakthrough idea was that these rules of thumb could be catalogued. And once understood they can be used to predict where people will make systematic errors. Those two words are what made behavioral economics possible.

Consider their famous representativeness heuristic, the tendency to judge probabilities by similarity. Use of this heuristic can lead people to make forecasts that are too extreme, often based on sample sizes that are too small to offer reliable predictions. As a result, we can expect forecasters to be predictably surprised when they draw on small samples. When they are very optimistic, the outcomes will tend to be worse than they thought, and unduly pessimistic forecasts will lead to pleasant but unexpected surprises. To the great surprise to economists who had put great faith in the efficiency of markets, this simple idea led to the discovery of large mispricing in domains that vary from stock markets to the selection of players in the National Football League.

Behavioral economists have now made important contributions to many domains of economics, and have utilized the findings of numerous other social scientists along the way. But none of this would have happened if Amos and Danny had not opened up the adjacent possible, by telling us about systematic biases.

_____

Eric R. Kandel

Recipient, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 2002; Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics, Columbia University; Author, The Age of Insight; In Search of Memory

Daniel Kahneman has not yet influenced my work on snails and mice, but I am only in an early point in my career and I still look forward to exploring his ideas in a molecular biological context in the future.

That said, he has influenced my life. His friendship, advice and thoughtfulness have enriched me significantly and I look forward to many more productive interactions. _____

Michael I. Norton

Associate Professor of Marketing, Harvard Business School; coauthor, Happy Money: The Science of Smarter Spending.

Danny Kahneman sets a nearly impossible standard for social scientists: design experiments that so perfectly (and subtly) capture two different versions of the world that you don't even need to see the results to have already learned something novel.

A change of a single word or a single number—think of "400 people will die" versus "200 people will be saved"—and readers are instantly in the shoes of people experiencing those two different versions, and immediately see how they would behave differently in those two worlds.

This ability to create two seemingly similar worlds that lead to such different behavior leads to a broader learning, a kind of counterfactual approach to the world: "Wait, if a few words can alter my own behavior, how much of what I think and do is influenced by other trivial factors? My mood? My level of sleep? What I ate for breakfast?"

In a research world in which complexity of design and analysis serves as a proxy for importance, his approach reminds us—both scientists and laypeople—that the most profound insight often derives from the most elegant design.

_____

Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Distinguished Professor of Risk Engineering, New York University School of Engineering ; Author, Incerto (Antifragile, The Black Swan...)

The Problem of Multiple Counterfactuals

Here is an insight Danny K. triggered and changed the course of my work. I figured out a nontrivial problem in randomness and its underestimation a decade ago while reading the following sentence in a paper by Kahneman and Miller of 1986:

A spectator at a weight lifting event, for example, will find it easier to imagine the same athlete lifting a different weight than to keep the achievement constant and vary the athlete's physique.This idea of varying one side, not the other also applies to mental simulations of future (random) events, when people engage in projections of different counterfactuals (we treat alternative past and future histories in exactly the same analytical manner).

It hit me that the mathematical consequence is vastly more severe than it appears. Kahneman and colleagues focused on the bias that variable of choice is not random. But the paper set off in my mind the following realization: now what if we were to go one step beyond and perturbate both? The response would be nonlinear. I had never considered the effect of such nonlinearity earlier nor seen it explicitly made in the literature on risk and counterfactuals. And you never encounter one single random variable in real life; there are many things moving together.

Increasing the number of random variables compounds the number of counterfactuals and causes more extremes—particularly in fat-tailed environments (i.e., Extremistan): imagine perturbating by producing a lot of scenarios and, in one of the scenarios, increasing the weights of the barbell and decreasing the bodyweight of the weightlifter. This compounding would produce an extreme event of sorts. Extreme, or tail events (Black Swans) are therefore more likely to be produced when both variables are random, that is real life. Simple.

Now, in the real world we never face one variable without something else with it. In academic experiments, we do. This sets the serious difference between laboratory (or the casino's "ludic" setup), and the difference between academia and real life. And such difference is, sort of, tractable.

I rushed to change a section for the 2003 printing of one of my books. Say you are the manager of a fertilizer plant. You try to issue various projections of the sales of your product—like the weights in the weightlifter's story. But you also need to keep in mind that there is a second variable to perturbate: what happens to the competition—you do not want them to be lucky, invent better products, or cheaper technologies. So not only you need to predict your fate (with errors) but also that of the competition (also with errors). And the variance from these errors add arithmetically when one focuses on differences. There was a serious error made by financial analysts. When comparing strategy A and strategy B, people in finance compare the Sharpe ratio (that is, the mean divided by the standard deviation of a stream of returns) of A to the Sharpe ratio of B and look at the difference between the two. It is very different than the correct method of looking at the Sharpe ratio of the difference, A-B, which requires a full distribution.

Now, the bad news: the misunderstanding of the problem is general. Because scientists (not just financial analysts) use statistical methods blindly and mechanistically, like cooking recipes, they tend to make the mistake when consciously comparing two variables. About a decade after I exposed the Sharpe ratio problem, Nieuwenhuis et al. in 2011 found that 50% of neuroscience papers (peer-reviewed in "prestigious journals") that compared variables got it wrong, using the single variable methodology.

In theory, a comparison of two experimental effects requires a statistical test on their difference. In practice, this comparison is often based on an incorrect procedure involving two separate tests in which researchers conclude that effects differ when one effect is significant (P < 0.05) but the other is not (P > 0.05). We reviewed 513 behavioral, systems and cognitive neuroscience articles in five top-ranking journals (Science, Nature, Nature Neuroscience, Neuron and The Journal of Neuroscience) and found that 78 used the correct procedure and 79 used the incorrect procedure. An additional analysis suggests that incorrect analyses of interactions are even more common in cellular and molecular neuroscience.

Sadly, ten years after I reported the problem to investment professionals; the mistake is still being made. Ten years from now, they will still be making the same mistake.

Now that was the mild problem. There is worse. We were discussing two variables. Now assume the entire environment is random, and you will see that standard analyses of future events are doomed to underestimate tails. In risk studies, a severe blindness to multivariate tails prevails. The discussions on the systemic risks of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) by "experts" falls for such butchering of risk management, invoking some biological mechanism and missing on the properties of the joint distribution of tails.

_____

Joshua D. Greene

Cognitive Neuroscientist and Philosopher, Harvard University

It's hard to overstate Kahneman's influence on my work. What I have done, essentially, is to look at moral thinking through the lenses ground by Daniel Kahneman. In my first year of college I was introduced to the field of "heuristics and biases" and was struck by the power of these ideas—that some of the most important decisions we make are deeply myopic. Soon after, I was introduced to contemporary debates in ethics, much of which center around moral dilemmas such as the Trolley Problem. These dilemmas boil the great debate in modern moral philosophy—Kant vs. Mill—down to its essentials, eliciting strong judgments favoring both sides. I felt that if I could understand the thinking behind those judgments I could understand a lot. Looking at these problems through my new Kahnemanian lens, I saw modern moral debate as a battle between morality "fast and slow," both in the brain and out in the world. I've been chasing down the implications of that idea ever since.

_____

Walter Mischel

Robert Johnston Niven Professor of Humane Letters, Department of Psychology, Columbia University; Author, The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-Control

"Answering an Easier Question"

I have known Danny Kahneman for more than 40 years, and am taking the liberty of bypassing the editorial instructions to avoid the personal and will mention how we first met. From my brief time as chair of the Stanford Psychology Department in the 1970s I recall two achievements: a new paint job and hiring Amos Tversky. Amos in turn brought Danny often into the Tversky's campus home. Some of my most treasured memories of that time were watching them thinking, talking, and laughing when they were at the height of their collaboration. Since then, I have avidly absorbed Danny's work, and enjoyed every conversation we have had. It has all influenced my own thinking, not only about our science, but about how to try to do it right.

My second violation of Edge's request to stick to ideas, not books, is to note that an extraordinary moment is occurring that is good news not just for Danny but for our science: Danny's serious book about how we think is being celebrated in London on the sale of its one millionth's copy in the UK alone. So, benefiting from his Thinking Fast and Slow, specifically Chapter 9, "Answering an Easier Question", I will use my space here not to address the question Edge asked, but to ask instead: How did he do it? Not just the book, but all of it.

Kahneman himself gives us some good hints in a short 2007 autobiography buried in volume IX of A History of Psychology in Autobiography in an APA series that may have more authors than readers. He tells us that he has consistently tried to use an approach he calls the "psychology of single questions" which he contrasts with the typical approach in psychological science in which "concepts are commonly associated with procedures that can be described only by long lists or by convoluted paragraphs of prose."

In one wonderful year he and Amos focused completely on the 1974 Science article that catapulted them into the history books. Danny attributes its remarkable impact (that ultimately also led to the Nobel Prize), to the medium as much as to the message. He notes that in the 1974 article he and Amos continued to practice the psychology of single questions. He believes that citing those questions verbatim in the text of the article: "personally engaged readers and convinced them that we were concerned not with the stupidity of Joe Public but with a much more interesting issue: the susceptibility to erroneous intuitions of intelligent, sophisticated, and perceptive individuals such as themselves." Forty years later the same voice and practice surely underlie the success of Thinking Fast and Slow.

Reflecting further on his collaboration with Tversky and the genesis of that 1974 article, Danny says they went through 30-odd versions of prospect theory. What kept them going was Amos' often-used phrase "Let's do it right." They did, and in what Kahneman has kept on doing, he keeps showing us how to get it right.

_____

Steven Pinker

Johnstone Family Professor, Department of Psychology; Harvard University; Author, The Better Angels of Our Nature

As many Edge readers know, my recent work has involved presenting copious data indicating that rates of violence have fallen over the years, decades, and centuries, including the number of annual deaths in war, terrorism, and homicide. Most people find this claim incredible on the face of it. Why the discrepancy between data and belief? The answer comes right out of Danny's work with Amos Tversky on the Availability Heuristic. People estimate the probability of an event by the ease of recovering vivid examples from memory. As I explained, "Scenes of carnage are more likely to be beamed into our homes and burned into our memories than footage of people dying of old age. No matter how small the percentage of violent deaths may be, in absolute numbers there will always be enough of them to fill the evening news, so people's impressions of violence will be disconnected from the actual proportions."

The availability heuristic also explains a paradox in people's perception of the risks of terrorism. The world was turned upside-down in response to the terrorist attacks on 9/11. But putting aside the entirely hypothetical scenario of nuclear terrorism, even the worst terrorist attacks kill a trifling number of people compared to other causes of violent death such as war, genocide, and homicide, to say nothing of other risks of death. Terrorists know this, and draw disproportionate attention to their grievances by killing a relatively small number of innocent people in the most attention-getting ways they can think of.

Even the perceived probability of nuclear terrorism is almost certainly exaggerated by the imaginability of the scenario (predicted at various times to be near-certain by 1990, 2000, 2005, and 2010, and notoriously justifying the 2003 invasion of Iraq). I did an internet survey which showed that people judge it more probable that "a nuclear bomb would be set off in the United States or Israel by a terrorist group that obtained it from Iran" than that "a nuclear bomb would be set off." It's an excellent example of Kahneman and Tversky's Conjunction Fallacy, which they famously illustrated with the articulate activist Linda, who was judged more likely to be feminist bank teller than a bank teller. _____

Nicholas A. Christakis

Physician and Social Scientist, Yale University; Coauthor, Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives

I heard of Danny in 1974 when I was 12, when my father, a nuclear physicist, handed me a copy of a paper that Danny and Amos Tversky had just published in Science. I first met him when I was in my 40's, when I had gone to Princeton to give a talk. And I now count him as a friend. But in the intervening decades, he had a profound effect on people like me who work at the intersection of the natural and social sciences—not so much (or only) because of the content of his thinking, but rather because of the manner of his research—because Danny's brilliant way of working highlighted how one could practice a beautiful kind of syncretic science.

Hence, Danny's work influenced my own not so much in what he did (though I always was stimulated by his ideas), but rather in how he did it. In this regard, I think the intellectual impact that Danny has had, and that I can discern both in myself and in many, many others, has been twofold. First, he has shown how conversations across broad swaths of science can take place. He created new knowledge not just by sheer force of mind, but also by seeing lacunae and overlaps and complementarities in disparate fields. Second, he palpably demonstrated how iconoclastic thinking is still the best kind of thinking in science—and how such thinking can still, sometimes, have a big impact in the course of a lifetime. If you want to discover something new, do something different.

These sorts of intellectual models are crucial to scientific activity, I think, and they are not mere clichés. One of the rewarding things about a life in science is that it affords one the opportunity to engage in a conversation, stretching back centuries, and spreading out over space and disciplines, with other kindred pilgrims. Danny provided not just a model of where to go, pointing in new directions, but also a model of what sort of light to use and what sort of rhythm of walking, and running, to adopt.

_____

Rory Sutherland

Executive Creative Director and Vice-Chairman, OgilvyOne London; Vice-Chairman, Ogilvy & Mather UK; Columnist, the Spectator

Loss aversion was, of course, widely understood by the advertising industry long before it was adopted by economists. The slogan "Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM" suggests that people might be willing to pay a significant premium to avoid the small chance of a disastrous outcome.

The advertising industry seems to have known about anchoring, too. It was a copywriter for the agency N W Ayer (possibly Frances Gerety, one of the models for Peggy In Mad Men) who wrote the headline for De Beers to promote engagement rings: "How else can a month's salary last a lifetime?".

Like the TV game-show industry, we managed to discover all this stuff on our own because, by a happy accident, almost no-one in our industry knew anything about economics at all. And therefore it never occurred to us to try to understand human behaviour by first pretending that emotions such as regret, embarrassment or mistrust do not exist.

By assuming "perfect rationality, perfect information and perfect trust", bad economics has created a world where efficiency is all that matters; where ethics, psychology and perception can be ignored; and (possible self-serving bias here) where brands, marketing and advertising should not exist. As one climate scientist said to me recently, if you ask any conventional economist "How do we get people to do X?" the answer, though dressed up in fancier language, always amounts to the same thing: "By bribing them to do it or fining them for not doing it." That is a very limited toolkit with which to work.

This being Edge, there are people far more qualified than I am to write about his work on Prospect Theory, Base-Rate Neglect, Hedonics, Affect Forecasting or—a personal favourite—on his "failure to disagree" with Gary Klein. What I can add from my own field is a note about another really important achievement of his last few years: the fact that he has become a brand. This is more important than you may think.

When I met Danny in London in 2009 he diffidently said that the only hope he had for his work was that "it might lead to a better kind of gossip"—where people discuss each other's motivations and behaviour in slightly more intelligent terms. To someone from an industry where a new flavour-variant of toothpaste is presented as being an earth-changing event, this seemed an incredibly modest aspiration for such important work.

However, if this was his aim, he has surely succeeded. When I meet people, I now use what I call "the Kahneman heuristic". You simply ask people "Have you read Danny Kahneman's book?" If the answer is yes, you know (p>0.95) that the conversation will be more interesting, wide-ranging and open-minded than otherwise.

And it then occurred to me that his aim—for better conversations—was perhaps not modest at all. Multiplied a millionfold it may very important indeed. In the social sciences, I think it is fair to say, the good ideas are not always influential and the influential ideas are not always good. Kahneman's work is now both good and influential.

We now think it perfectly normal that physical objects are designed to work with the way our bodies have evolved; this is why the keyboard on which I am typing this is reasonably congruent with the size of my hands, and why I do not steer my car with my nose. Yet many programmes and services are designed not for the brains of humans but of Vulcans. Thanks in large part to Kahneman and his many collaborators pupils and acolytes, this can and will change.

No comments:

Post a Comment