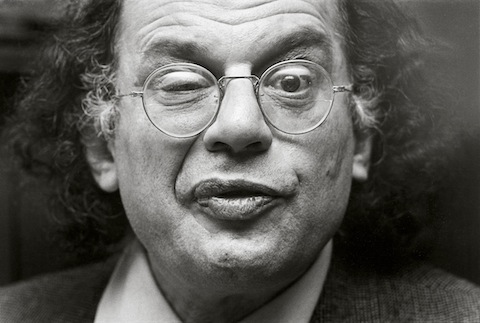

Allen Ginsberg's great American poem, "Howl," was for me (like so many others before and after) a pivotal moment in my understanding of poetry, of art, and of America. Before reading "Howl," I had help William Carlos Williams (Ginsberg's mentor) and Robinson Jeffers as the poets I from whom I tried to learn the craft of poetry. Ginsberg changed that.

Here is some biography from The Academy of American Poets:

He was admitted to Columbia University, and as a student there in the 1940s, he began close friendships with William S. Burroughs, Neal Cassady, and Jack Kerouac, all of whom later became leading figures of the Beat movement. The group led Ginsberg to a "New Vision," which he defined in his journal: "Since art is merely and ultimately self-expressive, we conclude that the fullest art, the most individual, uninfluenced, unrepressed, uninhibited expression of art is true expression and the true art."Below is the first ever recorded reading of "Howl," a major find for lovers of poetry, especially Beat poetry.

Around this time, Ginsberg also had what he referred to as his "Blake vision," an auditory hallucination of William Blake reading his poems "Ah Sunflower," "The Sick Rose," and "Little Girl Lost." Ginsberg noted the occurrence several times as a pivotal moment for him in his comprehension of the universe, affecting fundamental beliefs about his life and his work. While Ginsberg claimed that no drugs were involved, he later stated that he used various drugs in an attempt to recapture the feelings inspired by the vision.

In 1954, Ginsberg moved to San Francisco. His mentor, William Carlos Williams, introduced him to key figures in the San Francisco poetry scene, including Kenneth Rexroth. He also met Michael McClure, who handed off the duties of curating a reading for the newly-established "6" Gallery. With the help of Rexroth, the result was "The '6' Gallery Reading" which took place on October 7, 1955. The event has been hailed as the birth of the Beat Generation, in no small part because it was also the first public reading of Ginsberg's "Howl," a poem which garnered world-wide attention for him and the poets he associated with.

In response to Ginsberg's reading, McClure wrote: "Ginsberg read on to the end of the poem, which left us standing in wonder, or cheering and wondering, but knowing at the deepest level that a barrier had been broken, that a human voice and body had been hurled against the harsh wall of America..."

Shortly after Howl and Other Poems was published in 1956 by City Lights Bookstore, it was banned for obscenity. The work overcame censorship trials, however, and became one of the most widely read poems of the century, translated into more than twenty-two languages.

Hear the Very First Recording of Allen Ginsberg Reading His Epic Poem “Howl” (1956)

June 12th, 2013

Occasionally I slip into an ivory tower mentality in which the idea of a banned book seems quaint—associated with silly scandals over the tame sex in James Joyce or D.H. Lawrence, or more recent, misguided dust-ups over Huckleberry Finn. After all, I think, we live in an age when bestseller lists are topped (no pun) by tawdry fan fiction like Fifty Shades of Grey. Nothing’s sacred. But this notion is a massive blind spot on my part; the whole awareness-raising mission of the annual Banned Books Week seeks to dispel such complacency. Books are challenged, suppressed, and banned all the time in public schools and libraries, even if we’ve moved past outright government censorship of the publishing industry.

It’s also easy to forget that Allen Ginsberg’s generation-defining poem “Howl” was once almost a casualty of censorship. The most likely successor to Walt Whitman’s vision, Ginsberg’s oracular utterances did not sit well with U.S. Customs, who in 1957 tried to seize every copy of the British second printing. When that failed, police arrested the poem’s publisher, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and he and Ginsberg’s “Howl” were put on trial for obscenity. Apparently, phrases like “cock and endless balls” did not sit well with the authorities. But the court vindicated them all.

The story of Howl’s publication begins in 1955, when 29-year-old Ginsberg read part of the poem at the Six Gallery, where Ferlinghetti—owner of San Francisco’s City Lights bookstore—sat in attendance. Deciding that Ginsberg’s epic lament “knocked the sides out of things,” Ferlinghetti offered to publish “Howl” and brought out the first edition in 1956. Prior to this reading, “Howl” existed in the form of an earlier poem called “Dream Record, 1955,” which poet Kenneth Rexroth told Ginsberg sounded “too formal… like you’re wearing Columbia University Brooks Brothers ties.” Ginsberg’s rewrite jettisoned the ivy league propriety.

Unfortunately, no audio exists of that first reading, but above (or via these links: Stream – iTunes ) you can hear the first recorded reading of “Howl,” from February, 1956 at Portland’s Reed College. The recording sat dormant in Reed’s archives for over fifty years until scholar John Suiter rediscovered it in 2008. In it, Ginsberg reads his great prophetic work, not with the cadences of a street preacher or jazzman—both of which he had in his repertoire—but in an almost robotic monotone with an undertone of manic urgency. Ginsberg’s reading, before an intimate group of students in a dormitory lounge, took place only just before the first printing of the poem in the City Lights edition.

The recordings listed above all appear in our collection of 525 Free Audio Books. Just look for the Poetry section.

Related Content:

- Allen Ginsberg Recordings Brought to the Digital Age. Listen to Eight Full Tracks for Free

- Allen Ginsberg’s “Celestial Homework”: A Reading List for His Class “Literary History of the Beats”

- James Franco Reads a Dreamily Animated Version of Allen Ginsberg’s Epic Poem ‘Howl’

~ Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness

No comments:

Post a Comment