When the U.S. government over-reacted to the 1960s hippie culture and declared the hallucinogens Schedule 1 controlled substances (a listing generally reserved for substances that are addictive and without medical value), the underground chemists began to synthesize these drugs themselves. Particularly in the last 25 years, these chemists have created hundreds of variations of the basic hallucinogens, each designed for specific experiences or to offer specific duration of intoxication.

New York Magazine recently posted an article by Vanessa Grigoriadis that offers an introduction to the strange new world of designer psychedelics.

Travels in the New Psychedelic Bazaar

The synthetic drugs being invented, refined, and produced today—and often shipped in from China—would have blown Timothy Leary’s mind. Who knows what they’re doing to the brains of users.

By Vanessa Grigoriadis

Published Apr 7, 2013

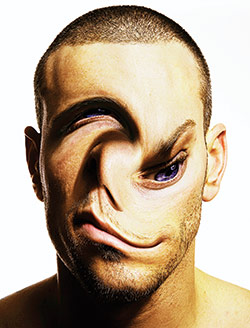

(Photo: Steve Smith/Getty Images)

A few years ago, on the West Coast, I made the acquaintance of a 32-year-old whom some people call “the Wizard.” He’s a nice guy, quiet, with a long beard that he wasn’t going to cut until Americans stopped killing civilians in our two wars, and a deep interest in organic chemistry. He was once a computer programmer and at another time a pot dealer. “It wasn’t uncommon for me to drive around with pounds of weed in my truck,” he says. “I’d just put on a hillbilly hat, load up the car, and throw tools in the back.” Now, though, he’d wandered through a different door and found himself in the midst of a bazaar of weird new drugs. In the Wizard’s offline world, which was made up of patchwork-wearing hippies and Rainbow Family elders, there was acid, pot, and MDMA, usually called ecstasy, and that was about it. But on the online forums he began to obsessively frequent, the Wizard learned about a vast array of new white powders. It was as if MDMA (now being called “Molly”) and LSD had somehow melded together, producing dozens of new psychedelic substances. On the forums, there were also whole new classes of dissociatives, stimulants, sedatives, and cannabis-based products (“cannabinoids”), along with a group of drugs called “bath salts,” which, of course, have nothing to do with Epsom salts or the lavender-scented kind purchased at Aveda.

The gray market for these new drugs, referred to as “research chemicals” or “synthetics,” has gotten little attention outside the tabloid media in the past few years, even as there has been worry about Mexican cartels and cocaine and heroin rings and medical-marijuana laws. It’s not a huge market, but it is a vivid one and fervent. For young guys interested in drugs today (and the users of these drugs are “150 percent male,” as one aficionado puts it), this underground scene of hobbyists and tinkerers, hippie-meets-hipster drug geeks, who like to call themselves psychonauts, there’s no better reason to try a new drug other than it happens to be just that—new. These drug users imagine themselves as amateur chemists, proto–Walter Whites, sampling and resynthesizing drugs to achieve exactly the state of consciousness they find most pleasurable. And there are no end of drugs to play with. As Hamilton Morris, the son of filmmaker Errol and a Williamsburg-based journeyman drug historian, as well as an independent chemist conducting research at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, has noted, this era “is to ecstasy what the Cambrian period was to arthropods.”

The Wizard claimed a highfalutin motivation for his interest in these drugs—it’s about studying the way that changing one’s brain chemistry alters consciousness, he says, and drawing conclusions from there about what “is” is—but it seemed to me that the drug-taking itself had become the thing. He was constantly scanning the forums to check out the best dosages and “delivery methods” of various drugs—discerning whether, say, E-Cat, a bath salt, was better taken buccally, insufflated, perhaps injected (though the Wizard didn’t like to do that), or “pegged” in a “shamanic enema,” which is lingo for putting a packet of drugs up the butt. Eventually, the list of substances that he tried, in addition to old standards like alcohol, heroin, MDMA, cocaine, marijuana, acid, ether, nitrous, hydrocodone, mescaline, and cubensis mushrooms, grew to include MDA, DOM, LSA, MDAI, DOB, DOI, DOC, DMT, K, GBL, GHB, TMA-2, AMT, BZP, 2C-B, 2C-C, 2C-D, 2C-I, 2C-T-7, 5-MeO-DiPT, 5-MeO-MIPT, 5-MeO-DALT, 5-MeO-DMT, PCP, MDE, 4-Acetoxy-DET, 4-Acetoxy-DiPT, FLEA, 4-FA, JHW-018, MPA, AM-2201, AM-2233, 4-MEC, 4-EMC, 5-APB, 6-APB, ALD, MXE, BHO, Bromo-DragonFLY, Salvinorin A, Soma, fentanyl, Dilaudid, Marinol, thujone, oxymorphone, hydromorphone, and some of the “bath salts,” which is just a catchy, consumer-friendly name for “synthetic cathinones,” a slew of amphetamines and MDMA-like substances invented in 2008 to mimic the chemical composition of the African khat plant. (In Belize, before his legal troubles, McAfee Virus founder John McAfee claimed to have synthesized, though he later walked this back, MDPV, a bath salt that he called “super perv powder” and that is supposed to feel like doing a bunch of meth and then, twenty minutes later, a line of very fine cocaine.*)

As we sit in front of a crackling fire at his neatly kept cabin in the woods, the Wizard smiles. “These are all awesome substances, if you know what to expect,” he says. It’s possible he may have missed a few drugs when he put together this list, he adds—given the hammering to his cerebrum over the years—but he feels satisfied that he could remember most of them.

The story that America tells itself about drugs, particularly psychedelic ones—that term, invented by Aldous Huxley, is preferred these days, since “hallucinogens” implies that one is not actually on a trip through one’s mind (or a universal mind) but seeing things that aren’t there—is that they exploded in the sixties and seventies, in circles like Timothy Leary’s and on Haight-Ashbury, then were demonized by the government and shortly dispensed with, relegated to being the plaything of curious college kids at Oberlin and Brown. These days, though, almost every drug, from pot to GHB to morphine, has been messed with, as chemists find that removing a methoxy group or adding a benzene ring makes a new drug with different properties: body-grooving with a side helping of visuals, euphoric or speedy, long or short, or administering just the right dose of primal fear. These man-made compounds were called “designer drugs” in the late nineties; you might have thought, as I did before I researched this story, that they had such a name because they were carried around by trendy types in designer Gucci handbags, but it refers to a chemist’s “designing” a new molecular compound that replicates the effects of an illegal drug.*This article has been corrected to show that McAfee only claimed to have synthesized MDPV.

(Photo: Steve Smith/Getty Images)

By virtue of being molecularly distinct, these newer synthetics now exist somewhere between the realms of legal and illegal, in the gray. That’s a big deal to most of the people who are drawn to them: those who are often drug-tested, particularly in the Army and Navy, or trying to dodge rehab (drug tests have yet to be updated for many synthetics); less affluent users who like the fact that a lot of these drugs are extremely cheap and sometimes even found in head shops; and kids who probably don’t even know a drug dealer, but they do know how to order things off the Internet. Most of these folks are looking for legal amphetamines. The Wizard’s crowd of underground psychonauts, probably made up of about 10,000 to 20,000 people, most of whom communicate through the forums, are a little different. They’re most interested in the ability to custom-match a substance with a desire—even if, in some cases, the new drugs are substandard to known ones (making your heart race; shoving you through a fractal landscape with elves coming out of the gloaming; making you feel weird, and not good weird, but bad weird). “You can pinpoint what you want now: ‘I’d like something of four hours’ duration with mescaline effects, or twelve hours’ duration with alternating mushroom and LSD rushes,’ ” says a 37-year-old software engineer whose activity in this realm has led friends to give him the nickname of Saddam Hussein’s poison-gas henchman, “Chemical Ali.”

One afternoon at the Jivamuktea Cafe near Union Square, Lex Pelger, a slight, unprepossessing 30-year-old with a degree in biochemistry, an evil eye pinned to his plaid shirt, digs past a copy of Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” and an invitation to a Bushwick burlesque party in his messenger bag, pulling out a creased, complicated chart of all the new synthetics. He points to the entry for the new hot synthetic psychedelic, the “N-bomb” (the NBOMe series), which resembles LSD in its effects but is shorter-lasting and cheaper, at about $1 per dose. You have to be careful with the dosage, which must be measured in submilligrams: “A tiny amount is so powerful,” Chemical Ali had told me. “I figured out that if you mix it with vodka and put it in a nasal-spray bottle, it’s a fifteen-minute come-up, peaks at an hour and a half, and you’re on your way out at two hours.” At Jivamuktea, Pelger takes a bite of his salad. “In New York, you can’t give acid away—it’s an entire day: ‘I have to do laundry,’ ‘I need to see this person,’ it sucks,” he says. “The N-bomb is less intellectual and about giant God questions than LSD, and a little bit more in your body—great for dates or art museums.” The last time he took it, he went to his favorite tripping spot in Prospect Park, then to the Asian-art section of the Brooklyn Museum. “There was this Korean pot that was so beautiful that I got it in my head that it was unsafe where the assholes and pigfuckers could see it, and I had to smash the glass and rescue it. It was the first time in a long time that I almost made a mistake with psychedelics.”

If you happen to be looking to vandalize a museum in order to rescue some Korean pots, obtaining these drugs is easier than you might imagine. Like everything else, the business of drug dealing is getting disrupted by the Internet. Some users download an encrypted web browser to purchase peer-reviewed illegal drugs on the website the Silk Road, but it’s far more commonplace for them to simply type “buy N-bomb” into Google, hit a site located abroad, and process fees through an anonymized payment service (some may rip you off, but that’s just part of the game). That the DEA has shut down U.S.-based vendors of these drugs doesn’t really have an effect on the end consumer, who still receives his package in the mail, usually stamped with a label reading not for human consumption on the front, in hopes of some protection from U.S. drug laws.

The bags usually come with a diagram of the drug’s molecular structure taped to the front, a nice wrapping paper, “and you could show it to a cop if you were ever stopped with a bag,” says one user, “and show him that the molecular structure of the drug makes it technically legal.” Like many others, the Wizard followed the recommended dosages for these drugs on Erowid.org, an online nonprofit sort of World Book of drugs that is funded entirely by donations. Run by a husband and wife, Earth and Fire Erowid (the names are pseudonyms), living outside Yosemite, the site has the slogan “Know your body. Know your mind. Know your substance. Know your source,” and some of its 59,000 pages of information were recently used as the most reliable source of human data on drugs in a study at UC Berkeley.

(Photo: Steve Smith/Getty Images. Photo-illustration by Joe Darrow.)

There are a few interlocking strands in this new drug culture, many familiar from previous movements, but this time woven in a different way. To start with, there’s the media and its fantasies (“MDMA makes holes in your brain”), and gurus delivering hoary mystical lore (“There is a cosmic mushroom mind”). And one could argue that drugs are an essential part of the futurist spirit of the moment, in full swoon with tech and science, and “now in the mainstream blossoming of the mid-nineties underground ‘techno pagan’ culture,” as author and psychedelic historian Erik Davis puts it. The process of selecting, sampling, and sometimes resynthesizing drugs is also connected to the do-it-yourself culture of computer hacking, another democratized technology. Many of these new experimenters feel that simply by journaling their experiences on the Internet, they are adding to the sum of scientific knowledge about these compounds—which, to a certain sort of person, means progress.

There has never been a time when we’ve been more open to the recognition that, as Hamilton Morris says, “everything is chemical in the world,” so there’s no reason to think that putting “chemicals in your brain, which is made of chemicals, is bad.” The right to put drugs in one’s own body is one that some people hold dear, a form of “cognitive liberty.” In the drug community, there’s utopian talk about what the future portends. “Every few months, we hear from someone who has just received their Ph.D. in pharmacology, chemistry, neurology, or psychology,” say the Erowids. “In 40 years, they will be senior researchers … The 2010s will be to the 2060s what the 1960s are to today.”

But there’s another way of looking at these preternaturally colorful developments. National emergency-room visits, the accepted metric for drug trends, found a record 49 novel compounds in 2011. “We’re starting to get a big-time problem with these new drugs,” says Rusty Payne, an agent at the DEA’s national office. “It turns out that we, as Americans, have an appetite for silly things like synthetics.”

For the wizard, Morris, and Pelger, the contemporary psychedelic idol isn’t Timothy Leary’s preacher man, or Terrance McKenna and his shamanic plants, though he’s beloved by those into ayahuasca, a psychedelic brew that Allen Ginsberg described as “a big wet vagina” or “great hole of God-nose.” Instead, it’s the original underground psychonaut and tinkerer: Alexander “Sasha” Shulgin, a Harvard-educated Dow Chemical scientist who left the company shortly after he discovered that MDMA had psychoactive properties (it’s thought that it was synthesized by Merck in 1912, by chemists looking for drugs to stop bleeding), and has basically been a one-man R&D department for synthetic drugs for the past 50-odd years. In his home lab in the Bay Area, which for decades was semi-sanctioned by the DEA (agents liked to be able to call him when something esoteric crossed their paths) and ignored when the politics in the country started to change, Shulgin made over 100 completely novel drugs and many more variations on a theme. He tried them himself, along with a small circle of friends called his “research group” and his wife, Ann, whom he seduced through chemistry. After imbibing his compounds, the couple engaged in “absolute truth-telling,” with Rachmaninoff forming “huge petals of sensuous violet and pink, with a stamen of glowing yellow,” finally stripping their dressing gowns for lovemaking and then sitting quietly to type “experience notes” and eat a bowl of thick Dutch split-pea soup.

The Shulgins might sound like Santa and Mrs. Claus, but Sasha’s choice to publish all the recipes for the drugs he made in two enormous “cookbooks,” titled PiHKAL and TiHKAL (“Phenethylamines [or Tryptamines] I Have Known and Loved”), was actually quite subversive. Not only did he often refrain from using illegal “precursor chemicals” when chemically composing his drugs, but he was also able to retain legal use for awhile for most of them even under the Federal Analog Act of 1986, which says that any chemical that is “substantially similar” to a controlled substance is illegal.

In fact, the recipes in his books formed the entirety of the designer-drug market in the nineties. The most popular was 2C-B, a euphoriant Shulgin described as “unbelievably erotic, quiet, and exquisite.” For these drugs, and other phenethylamines, Shulgin substituted around the phenethylamine skeleton, adding different groups of molecules to create brain stimulants, central-nervous stimulants, or more and more serotonin, which starts to create hallucinations. “I like Shulgin’s 2Cs a lot,” says Chemical Ali. “2C-D is strictly visual; 2C-P is twelve hours long; 2C-B is my favorite, because it’s an ecstasylike experience—not that you’re in a cuddle puddle or anything, but you do feel good.”

Today, most of Shulgin’s compounds are gone—he supposedly burned many of them, which Morris, the self-styled drug historian, expresses dismay about, because “to burn such a thing would be like burning a painting.” Now 87, Shulgin has had multiple strokes and is suffering from dementia, and friends are soliciting donations for his care, reminding others to “think of all the ways that your life, and the lives of others, have been healed, transformed, and bettered by this wonderful man.”

Before he became incapable of inventing new drugs (colleagues don’t believe that Shulgin’s drug use added to his dementia), the research-chemical market started to change. Things ramped up in 2000, in part because the DEA managed to catch William Leonard Pickard, thought to have been the biggest LSD manufacturer in the world. Pickard’s lab, with Persian rugs and a $120,000 stereo system, was located in a decommissioned missile silo near Topeka, Kansas. The DEA claimed the lab was capable of producing 2.8 billion hits, though Pickard disputed this figure, claiming he only had precursor for 15 million hits. Acid suddenly became very scarce in the U.S. Users had to become open to trying new drugs. At the same time, online forums like Bluelight and Drugs-Forum introduced locked advanced-chemistry sections, where chemists of all stripes—from university professors and Ph.D.’s to amateur hobbyists like the Wizard—were able to communicate for the first time.

On a recent evening, I went to tea with Morris, a handsome 25-year-old with the desiccated–Ivy Leaguer look of a Vampire Weekend musician, and the six-one, 120-pound form of someone who couldn't care less about normal sustenance—often he just drinks a mix of vegetable and protein powder shakes for lunch and dinner. “When I was younger, it seemed impossible to me that one human being could make so many novel compounds—Shulgin’s work, I thought, would take 100 lifetimes—but the truth is, one committed chemist working in a lab can make a new compound almost every day, and very quickly will make hundreds,” says Morris.

We’re talking about the evolution of the synthetics industry, which Morris has been closely watching and chronicling for Vice magazine. Morris says that, with notable exceptions like some designer benzos, Ph.D.’s at mainstream university labs made most of the big innovations in post-Shulgin synthetics, mostly while developing drugs for other purposes. For example, the N-bomb was a product of a Free University of Berlin chemist who was researching schizophrenia. “Synthetic cannabinoids” were discovered by Clemson University professor John W. Huffman when he probed cannabinoid receptors to regulate nausea and appetite during cancer treatment.

Patents for these drugs are easy to find on Google Patents. That’s where many underground chemists and research-chemical vendors look for new drugs to synthesize, in hopes that their quasi-legal nature will help them get rich while staying out of jail. Once the drugs are on the market, gray-market tinkerers take them into their own labs or study them and make modifications—some members of the advanced-chemistry forums made variations on Huffman’s synthetic-pot group, for example, each with its own trip.

Academic researchers aren’t happy about this, for the most part—the theft of his patented drugs, Huffman has said, is a “royal pain in the rear end.” They truly did not intend that these drugs would be taken by humans. There aren’t even tests on rats for some of this stuff.

But with no FDA, making large batches of these drugs is surprisingly easy. All you have to do is send a CAS number (chemical I.D.) to the one country in the world that’s best at making all sorts of weird chemicals, from HGH to soy sauce to the plastic goo that forms Walmart toys—China. Morris has checked out a couple of Shanghai labs where vendors outsource drug production and says they make other drugs there, like off-market Viagra. “The [Chinese plants] may not be up to the standard of a Merck pharmaceutical manufacturing plant, but many are producing high-purity products, with surprisingly few compounds containing dangerous contaminants” or misidentified ones, he says, describing standing on a shipping dock with barrels of synthetic pot doubtlessly headed for the U.S.

For most underground psychonauts, direct-from-China is now the preferred source of drugs, other than a clandestine chemist who can be trusted, and with China in the picture, there are fewer and fewer of those in the U.S. “Clandestine chemistry is a dying American folk art,” says Morris.

Says a law-enforcement official, “China’s a mess. We’re not going to go over there and just tell them they’re dropping the ball. It’s being done, but sensitively. It’s a monster challenge.”

Underground psychonauts like the Wizard and Chemical Ali might not be as accomplished researchers as Huffman, but they think about their drug use as research, too, and keep their own notes on their experiences, just as Shulgin did. Unlike some users’ “trip reports” on the forums, which say things like “in the presence of the God-head I forget who and what I am,” “the time has come for change, and the change is paradise,” “I felt like my heart was being flogged by a miniature devil,” or declare “nothing made sense!!!,” the Wizard’s usually kept things light. His report on 16 milligrams of 2C-E reads: “At 1:30am, Tera, my girlfriend, has vomited two times now. (Sidenote, she vomits on everything, including water.) We have been listening to a wide range of music, however the choice songs of the night were ‘Lodi Dodi’ by Snoop Dogg and ‘The fluffy little clouds’ by the Orb. What a combination, eh? Paul compares it to 5 hits of LSD and 75mg of MDMA. Tera and I disappear occasionally through out the night for the sexual escapades that 2c-e always has on us. At about 3am, we go back upstairs and Paul and I rant a while about the U.S. government and such. (Sidenote, pre-rolled joints are required if you plan to smoke weed during your trip, LOL.) Overall, the experience was wonderful, however I still prefer the 20mg dose, as it’s almost double the intensity.”

Offline, the drugs began to dribble into the hypersocial 24-hour YOLO party-people scene, particularly among the older crowd—“gravers,” or adult ravers, in neon and feathers—and among the BDSM community. The Wizard was even playing with his sexuality, coming out as bisexual and establishing a “Temple of Discord” with a big pink lacquered cross in his three-car garage. Some in the polyamory scene, of which Pelger is also a part, are embracing the new ketamine drugs, like 3-MeO-PCP. “Those are lovely—the best sex drugs and dissociatives out there, I would say,” says Pelger at Jivamuktea. “Longer than K, about two hours, a little goopier, a little less boundaries between skin.” He pauses. “It’s great for people in the kink community, too. If you want to do some hard play, like take your sex-worker girlfriend, knock her out for two hours, and have men come in and fuck her and film it and let her wake up and watch it, then it’s a safe way to do that.”

Of course, dangerous games become not games at all if someone forgets where the lines are. That’s always been the thing with heavy drugs, mental structures can give way without warning, which can be exhilarating—or something else.

As he got deeper into drug use, the Wizard began living a Summer of Love lifestyle in a contemporary world, and as it turned out, it wasn’t that hard to do. He began taking road trips up and down the West Coast in a 1979 Chevy school bus, though he soon flipped it for a regular car—it turns out that it costs a lot in gas to drive a school bus a thousand miles. He bought a scale and reagent tests so that he could be sure of what he was taking—put a little bit of the solution, usually mixed with sulfuric acid, on the drug, and it turns a different color for each type. He also started calling himself a “harm-reduction specialist,” offering “medical missionary” services at underground parties, and wrote this ditty:

Traveling from town to townIt sounds wholesome. But it was so easy to cross the line from drug fan to DIY chemist—doing simple extractions of DMT and salvia and learning about more advanced chemistry from someone making AMT and 2C-I—and, from there, a small hop to selling these wares. Soon, he and his friends were dealing drugs at festivals like Earthdance, the Oregon Country Fair, and Bonaroo, which he calls “Bustaroo” because a friend was busted there. “He got high on a Greyhound and ended up passing out waiting at a layover,” says the Wizard. “When the police woke him up, they found a few pounds of mushroom and 500,000 hits of a research chemical called DOB.” He strokes his beard. “The cops said he was a chemist, but I know enough to know that he wasn’t the chemist.”

From show to show

Testing that shit, and letting them know

With his laptop in hand he’s ready to post

Wherever he’s at from coast to coast

Be it pills, liquid, powder, or gel

Best rep it properly or else he’ll yell

Letting people know what the drugs

really are

Mecke

Ehrlich

Mandelin and Marquis

[various names of reagent tests]

He’ll even show up to test at parties

So the next time that you are at a show

Ask “who has a test” and then you’ll know

That the harm reduction

specialists are far and few

But they’ll tell you what’s in a pill,

and not just that it’s blue

This sounds like such an interesting world, doesn’t it? There’s only one problem—unlike with LSD, pot, or mushrooms, which are known to be among the safest drugs on the planet, people die from synthetics. Not a lot. But a few. Bromo-DragonFLY, a drug pilfered from the Purdue University lab of pharmacologist David Nichols for commercial release and considered to be the strongest serotonin agonist in the world, caused some people to lose their arms after taking high doses. “It clamped down so much on the blood vessels that the limbs die—you’re literally strangled from the inside,” says Jeff Lapoint, a medical toxicologist and emergency physician at Kaiser Permanente. After hearing stories like this, Chemical Ali and his group of “fellow travelers” decided to take a “threshold dose” of 1 milligram of each package they get in the mail and wait a day, for safety reasons. The Erowids even advise users of esoteric drugs to have a blood-pressure and pulse-monitoring device on hand. “When one takes a new and unstudied drug, one makes oneself a human guinea pig,” they say. “The drug may be perfectly safe. It may even be beneficial. On the other hand, after three uses one might suddenly find one’s body frozen up with symptoms resembling Parkinson’s disease.”

Then, of course, there are the freak-outs. It’s been impossible to miss these stories in the news, which loves a zombified drug-apocalypse story as much as it did during Reefer Madness in the twenties and doesn’t care much if mental illness enters the picture. On the N-bomb, an actor on FX’s Sons of Anarchymurdered his landlady in the Hollywood Hills, dismembered her cat, then killed himself. Bath salts have been blamed, among a zillion such stories, for making a Pennsylvania couple “slash their 5-year-old daughter repeatedly as they attacked the ‘voices in the walls’ ”; a guy in Maine get off his motorcycle and try to hit cars with a piece of wood; a woman try to cut out her teeth with a knife; and a man at a Tampa nightclub named Rat Soap fall into a bath-salts-induced seizure—clubbers tried to save him by putting a Valium in his mouth and wrapping him in plastic, but he died.

And who can forget the cannibal in Miami? That’s the Haitian guy who abandoned a purple Chevy (Koran in the back seat) and ripped his clothes off on the causeway, attacking a 65-year-old homeless man for eighteen minutes. Cops had to shoot him six times to get him to stop, at which point only 20 percent of the victim’s face remained intact, mostly a goatee. The media storm over this attack got so intense that Chuck Schumer, the government’s loudest advocate for making these drugs illegal, was able to push a new federal synthetics act past the opposition of Rand Paul and others. In the summer of 2012, Obama signed it into law, making most of the 2C class, as well as a few bath salts and Huffman’s drugs, illegal, with manufacture and sale punishable by up to twenty years in prison.

That the day after the synthetic-drug-control bill was passed the coroner finally released a toxicology report showing the cannibal was high only on THC, the natural kind, is neither here nor there. The more important fact is that it took only a few months for vendors to start selling a new set of drugs: The cannabinoids went from AM-2201 (illegal) to UR-144 (legal), and there was suddenly a new bath salt called a-PVP, which users on the forums declared good, although it “smelled very much like sperm” when insufflated. The trip is far from over.

The wizard seemed as hale and sharp as a 32-year-old ingester of hundreds of unknown drugs can be expected to be. Which didn’t mean that he was unscarred by his experiences. In his life, he felt that fate had always been on his side, but weird things started to happen. In fact, his local post office told him that his packages were being watched. Then an ex-girlfriend stole a bunch of synthetics and $40,000 from him; a few days later, she was stopped speeding in a construction zone and consented to a search of her car. The cops seized 2C-I, 2C-E, LSD, oxycodone, ketamine, MDMA, and a rare GHB “pro-drug” (whose chemical composition, different from GHB, is converted to it by the body’s enzymes when ingested) that the law-enforcement lab had never seen before. “There’s pictures of my pink-elephant blotter 2C-I on the DEA’s website because of that!” says the Wizard. As his business expanded, he began working with a lower-level dealer, a guy he knew from high school, who was “all about making money, and misrepresenting things, like a lot of people are,” he says. “He’d call 2C-I ‘synthetic mescaline,’ which it is technically a derivative of, but it’s not, at all.”

A couple of months later, the lower dealer was caught capping off a pistol at a lake. The cops took him in, and he said he had something to tell them if they’d let him off on the charge—he could turn them on to a major source of acid. When the dealer came back to talk to the Wizard, he told him that he’d met some guys who were “big fans” of his work, and the Wizard’s ego, the thing he was supposed to be destroying with all this, got puffed up. He gave the informant 2C-I, 2C-B, and Bromo-DragonFLY, but the agents kept asking for “real acid”—they didn’t want to deal with prosecuting someone in an analog case, which can be hard to win because juries are easily confused by chemistry.

The Wizard said he’d see what he could do. A week later, he put twenty vials in a Starbucks bag, a taste before they said they’d purchase two raw grams, and went to meet his friend at the mall. “Suddenly, there were five SUVs all around me, and guys in plainclothes with guns—honestly I thought we were getting robbed,” says the Wizard. “I might have been a little high.” When he said he wanted a lawyer, “the cops said, ‘Shut up, this isn’t a movie.’ I said, ‘Oh, they don’t have civil rights in movies?’ I got in the cop car, and just to be a dick, I said, ‘How much do I need to pay to get out today?’ ‘You’re not getting out today,’ the cop said. ‘We’re the DEA.’ That’s when I shut the hell up.”

The prosecutor on the Wizard’s case was interested in whom he knew, but he refused to talk. He might have run, but for the ankle bracelet. His friend, a naturopath once close to Shulgin, said that they could found an institute for research chemicals on Native American land. In the end, the judge was relatively lenient: The Wizard was sentenced to five years in federal prison.

The new psychonauts are comfortable with the notion that their explorations will have casualties, that all of the seekers won’t necessarily make it back. “All of this [experimentation] is producing valuable toxicological information that would never exist otherwise,” says Morris, who also notes that if the government hadn’t made so many drugs illegal, probably no one would be taking synthetics and risking their lives at all. “Because of THC’s benign nature, cannabinoids have long been considered one of the safest drug classes,” he says, “but now there are instances of people becoming addicted to synthetic cannabinoids or even reports of death.”

Besides, even scientists inside the academy believe that these drugs have uses beyond Burning Man. “These research compounds have the potential to teach us something about brain chemistry and different neural circuits—they’re potentially gold mines of information,” says Julie Holland, a New York psychiatrist and editor of a book on cannabis and another about MDMA. She talks about a study in Arizona using psilocybin to treat OCD. “Are you going to get those people high on mushrooms every day? No. But is it possible that the mushrooms are targeting a particular receptor beyond the way that Prozac or any other SSRI works?” It’s a matter of refining the medicines we have. When your car needs oil, you don’t just lift up the hood and pour oil on the engine. “It’s possible that SSRIs that flood the entire brain with serotonin aren’t the answer—maybe working on one circuit where your anterior cingulate is.” Holland believes that it’s a foregone conclusion that the next decade will include a new generation of Big Pharma meds based on marijuana. “You’re going to have medicine for inflammation and metabolism tickling the cannabis receptors—they’ll act like cannabinoids, but aren’t going to get you high.” (Harvard Medical School professor John Halpern recently started a company, Entheogen Corp., to develop 2-bromo-LSD, a non-hallucinogenic LSD analog, to treat cluster headaches, one of the most painful conditions in medicine.)

Some academics who study drugs view the research-chemical scene as an annoying sideshow, pointing out that it’s pretty hard to tell the difference between drugs in the same class with similar durations (MDMA and 2C-B, for example). The focus, they think, should be on gaining mainstream acceptance of old-line psychedelics, and they’re excited about current studies on psilocybin, the magic in magic mushrooms, for end-of-life care at Johns Hopkins and NYU. A privately funded group, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, is studying the ways MDMA can help soldiers with post-traumatic-stress disorder (therapists schedule sixteen non-drug sessions as well). Their goal for the next ten years is to reinstate the original use of MDMA, which was embraced by the psychiatric community in the seventies, and force the FDA to approve prescriptions for use during therapy.

The pathology of the underground psychonaut isn’t hard to imagine, and not that different from the video-game addict or extreme-sports obsessive—someone who also likes the rush of alternative reality more than the quotidian one. Real life can remain at a standstill, with jobs and relationships less important than surfing the edge. The possibility of addiction isn’t to be underestimated. “The reward circuit in the brain is very clever,” says Richard Friedman, director of the psychopharmacology clinic at Weill Cornell Medical College. “When you’re off the drugs, the background pleasure state of your brain may be changed for a week, a year, or even permanently. This is a wild social experiment.” Nevertheless, some users say they’ve had spiritual breakthroughs. “I know now that there’s more to the world than science has been able to explain so far, and it’s not to be feared,” says Chemical Ali. “I don’t have a death wish, but I’ve practiced death. When it happens, it will be fun, a cool experience.” He’s talking to me on the phone with a Björn strapped to his chest, and the baby boy inside, only a few weeks old, starts to wail. “I do feel like I should put this stuff away, at least for a while,” he says, “because I have something to live for.”

The Wizard’s story is a cautionary tale, almost a parable, but the government may start to take a closer look at this world. The Feds even recently scheduled 2C-N, a necessary intermediate for the manufacture of many synthetic drugs, though it doesn’t actually get you high—but it is useful in a synthetics lab. Morris calls the current situation an “infinite game of cat and mouse,” where the government schedules a drug, then chemists race to find a new legal compound. “Three weeks ago, we had our first detection of new derivatives, PB-22 and 5F-PB-22,” says Kevin Shanks, a forensic toxicologist in the Midwest. “Quinoline derivatives are uncontrolled by the federal government, and I see them becoming prevalent very quickly.” Adds Lapoint, the toxicologist: “Until we can break the model of releasing a new chemical that retains the same affinity for the receptor of an illegal drug but is structurally dissimilar enough that you can avoid getting popped, this is the new normal. Brick-and-mortar quasi-legal head shops are hard enough to stop, but the Internet vendors are fully whack-a-mole … The new drug dealer is the mailman.”

Will the cat finally catch the mouse? Some psychonauts fear that the government, in desperation, might take a pharmacodynamic backward approach, looking at the receptor activated by the drug and scheduling backward from there, claiming that any organic molecule that binds to the CB1 receptor and makes you stoned is a schedule 1 drug. * But then they’d have to schedule other drugs with CB1 affinity, including Tylenol. And they’d be “banning specific states of consciousness,” says Morris. “If the plan weren’t so futile, it would be utterly terrifying.”

Lapoint starts spitballing about what may happen in the future. “If I was a [research-chemical drugmaker], I’d want to make a structure of an endogenous chemical,” he says, “one that’s already in your brain and [can be enhanced] to hit the right neurotransmitters to get you high. The problem is that if you took this drug out of your brain and tried to eat it, it would be quickly broken down by enzymes. But you could tweak these [naturally occurring] structures, or add a substance that inhibits these enzymes, and you would get a psychoactive effect.” This would surely stump regulatory officials. Lapoint is completely against the proliferation of these drugs—he’s not interested in more patients in his ER. Still, as a man of science, he can’t but marvel at this type of reverse-engineering. “Whoa,” he says. “That would be really cool.”

*This article has been corrected to show that the psychonauts fear the government's approach will be "pharmacodynamic backward," not "pharmacode dynamic password."

No comments:

Post a Comment