Cosmopolis

Director: David Cronenberg

Cast: Robert Pattinson, Juliette Binoche, Sarah Gadon, Jay Baruchel, Mathieu Amalric, Kevin Durand, Paul Giamatti, Samantha Morton

(Entertainment One; US theatrical: 17 Aug 2012 (Limited release); UK theatrical: 5 Oct 2012 (General release); 2012)

Here are three reviews - from the Acceler8tor, Pop Matters, and Esquire.

Cronenberg’s Cosmopolis: The Quantified Life Is Not Worth Living

By R.U. Sirius

August 28, 2012

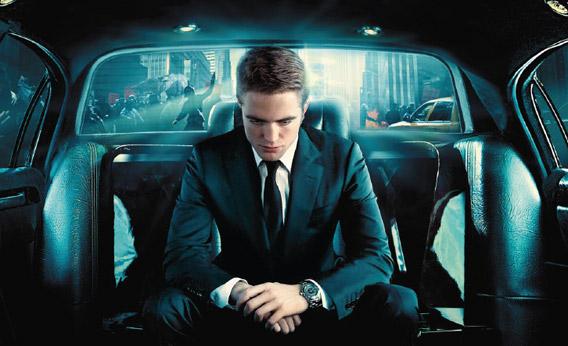

Eric Packer (played by Robert Pattison) — reigning master of the universe of unencumbered digital financial trading — spends most of his disastrous day in the back of a limo determined to make it across New York City in the midst of traffic chaos caused by a presidential motorcade, to get a haircut, but not, as we will discover, any haircut.

Impeccably dressed, physically perfect, emotionally smooth, and despite a series of sexual encounters during this single day with beautiful female subordinates — Packer’s world, until today, is nothing but data.

At the beginning of the film, we see massive data flows zipping around a small computer screen operated by a hacker employee, and we understand that his world of unfailing predictions based on this data has been disrupted by an error that threatens him with massive financial losses. But Packer, despite the seeming practicality of the bad day he is facing, is more interested in his existential situation. He’s having a crisis of meaning and of feeling.

As he and his driver make their way through NYC’s jammed streets, various courtiers slip into his limo to talk about some aspect of his business situation only to be peppered by stark questions that tilt away from business and lean towards meaning. And yet, his quasi-philosophical inquiries are all oriented towards calculation as opposed to insight (and how many of our singularitarian friends would acknowledge that a distinction exists). Packer is in the vanguard of his generations’ and our culture’s reorientation from lived to statistical experience.

The film hinges on two particular events. Event one: Packer’s previously unfailing prediction machine has failed to predict a crisis in the yuan. Event two: Packer’s daily medical examination turns up a peculiar (and contextually funny) problem that I won’t spoil for you… but both problems revolve around the incursion of irregularity into his smooth world.

Here we have the Quantified Life at its apotheosis. Even in the midst of sexual encounters, there are conversations that seek information about the nature of the business and sexual relationships and — during the peak of one sex scene — his female partner reports on her successful jogging routine and provides a statistical particular about her fat-to-muscle ratio.

In mixed reviews, much has been made of Cronenberg taking on Wall Street capitalism (and let’s remember that all this is based on the critically underrated DeLillo 2003 novel of the same name) in a biting satire that’s not at all a comedy. There is that. But the critics miss the larger undercurrent, which should have clarified for them during the last scene (and I will spare you any further spoilers). Several shocking scenes (yes, this is Cronenberg), including the finale, bring home for us that Packer is seeking some experience — any experience — that is not quantifiable. Whether he finds it or not, I’ll leave for you to sort out.

Oscar Wilde famously said of his countrymen, “They know the price of everything and the value of nothing.” But he was thinking of craggy old industrialists who actually traded in things. For Packer, price and value are both de-prioritized by the ersatz bliss of those baptized in dataflow. It’s a cold but pleasurably high, until something unsmooth, like a poor person or a bodily peculiarity, makes an unpredicted intervention.

* * * * * * *

Patter

The first thing you notice is that the limo isn’t moving. At the beginning of David Cronenberg’s Cosmopolis, the luxury vehicle bearing Eric Packer (Robert Pattinson), a billionaire financial manager of some sort, is stuck in traffic. He’s on his way to get a haircut on the other side of Manhattan, a trip he insists on taking despite warnings from his bodyguard Torval (Kevin Durand) that it will be nightmarish.

Even though the car does transport Eric to a series of stops, interior shots deny the audience a sense of true forward motion. When the limo pushes forward, the images of the city we see through the windows look fake, and familiar New York background noise falls silent: no honking horns, no engine vibrations, hardly any sound at all, except the voices of Eric and whoever hitches a ride with him along the way.

This lack of sound exists whether the windows are open or closed—as Eric does when he has sex with his longtime mistress Didi (Juliette Binoche). It underscores a sense of fakeness for much of the film, as well as the metaphorical allusion of the drive: Eric is going nowhere. The world comes to him in his limo-shaped box: business, sex, even regular prostate exams from his doctor.

Cosmopolis never breaks from Eric’s point of view (Pattinson is in every scene), following him as exits the vehicle, as when he takes meals with his wife Elise (Sarah Gadon). They might be described as “estranged” if they ever looked to be more than cordial strangers in the first place. They speak to each other, as most of the characters in the movie do, in dialogue that is by turns witty, elusive, and theatrical. The writerly quality reminds us that Cronenberg’s screenplay adapts a Don DeLillo novel, making some narrative tweaks while maintaining much of the original dialogue.

The elevated patter, combined with the financial-world setting, at first seems to signal that Cosmopolis is a departure for the director, both from his creepy sci-fi horror days and his recent collaborations with Viggo Mortensen. But as the movie presses on, it feels more of a piece with Cronenberg’s oeuvre, unnerving and darkly funny. Eric’s semi-mobile fortress is tricked out with a number of touch-screens, their numbers constantly scrolling through his peripheral vision, and his various business associates talk in elevated, obtuse terms—Vija (Samantha Morton) drops by the car to talk about “cyber-capital”—that give the film an eerie science fiction-like quality.

From these otherworldly touches and a constructed New York City that only vaguely resembles the real thing, Cosmopolis builds surprising tension from what is essentially a 24-to-36-hour car ride (time is hard to measure here, another subtle source of anxiety). It is by no means a traditional thriller, but Cronenberg evokes a sense of dread, exacerbated by occasional, unpredictable bursts of violence. By the movie’s final stretch, Eric finds himself drawing a gun and walking down an icky greenish brown hallway that’s more recognizably Cronenbergian than his antiseptic white limo.

As usual, Cronenberg shows masterful control, starting with Pattinson. He uses the actor’s morose flatness to great effect. Playing a hollow, amoral human being, Pattinson is more hauntingly vampiric here than in any of his Twilight ventures, an impression emphasized by his occasional stumbles over DeLillo’s words.

Some audience members will stumble there, too. An hour and 48 minutes is a long time to listen to actors, however talented, speak in more or less the same narcotizing tones, dotted with zingy turns of phrase and stagy variations on phrases like “This is true” and “I know this.” The artifice can seem showboaty, an odd fit with Cronenberg’s precise, repetitive framing. But the film is premised on contrasts, especially between such verbal gobbledygook and the social unrest just outside Eric’s bunker on wheels; he’s bedeviled by an ongoing anti-capitalism protest, whose participants use dead rats as mascots, a backdrop drawn from DeLillo’s 2003 text that here feels vague and unnecessarily allusive.

But, just when the movie threatens to find a dead end in so much metaphor, Paul Giamatti turns up to bring it home. Playing Benno Levin, an unhinged man with a connection to Packer, he dominates the movie’s final stretch, which moves further from the limo’s comforts, down that greenish Cronenberg hallway. The car’s literal forward momentum stops, but the film’s keeps crawling toward an ending both poetic and inevitable—and, yeah, a little theatrical, too. Cronenberg and DeLillo’s clinical remove gives way to showmanship after all.

6 Stars

* * * * * * *

Cosmopolis: This Is How Capitalism Ends

Intentionally or not, movies in the past year or so have set about tackling the questions of Occupy Wall Street and/or our general economic gloom. The Dark Knight Rises pitted Batman's Have against Bane's Have-Not, the conclusion of which was... well, no one's quite sure about that. Margin Call dramatized a day in the lives of investment bankers who talk like Wall Street Journal op-eds. Spike Lee, to no one's particular surprise, has sketched the effects of our growing economic inequality on a Brooklyn neighborhood in Red Hook Summer. And in next month's Arbitrage, Richard Gere, in the grand tradition of actors giving moral complexity to assholes, will play a hedge-funder who's basically Bernie Madoff. They all take a cue from Wall Street, the movie that made wariness of investment bankers a social norm and now looks all the more naive for it.

Thankfully, then, there is David Cronenberg. From Videodrome to Crash to A History of Violence, the director has never felt the need to seriously address the real-world concerns of the day, or even adhere to conventional narrative logic. (Holly Hunter wrecks her car, then masturbates? Why not?) His new movie, Cosmopolis, is a great send-up of our economic anxiety. It's true that the characters talk endlessly, as they do in Don DeLillo's 2003 book, but none of it amounts to much. It's empty banter, a parody of boardroom jargon. Robert Pattinson as an even less likable Bud Fox type named Eric Packer (the actor's flat, charmless American accent has never been better suited to a role) asks his employees inane questions they can't possibly hope to answer, like "Why are airports called airports?" They refuse to respond out of fear they'll lose his respect.

All the talk avoids the real subject, which for Cronenberg is never far from death. As Pattinson's Eric loses his personal fortune over the course of a day, his life becomes a series of escalating body-horror gags. There are two security threats against him, one of which turns out to be a literal pie in the face. The best joke, though, is a scene in which he receives a prostate exam while discussing the yuan. (For Cronenberg, that's "sexual tension.") By the end, Eric has become so disillusioned with himself that he sees violence as a way out. He shoots a hole through his hand just so that he can "feel something."

Movies are very bad at explaining our national problems to us (see: any film by Michael Moore). At their best, they can only make those problems more vivid. Cosmopolis takes an unremarkable proposal, that our economic system is hurtling toward chaos, to its logical conclusion. (The opening shot of a Pollock-style drip painting in the making is a sign of what's to come.) It's effective for all the reasons, as propaganda, it's not: It's messy and goofy and unsettling. It has no clear answers, not even in the brilliant final scene, a confrontation between Pattinson's Eric and a disgruntled former employee played by Paul Giamatti, the central question of which seems to be, Why do some people accumulate massive amounts of wealth, while others are left to go broke and die? The scene ends, instead, with a loaded gun.

Our own Wall Street becomes more absurd with every day's headlines. It's unclear if anyone really understands it, including the Wall Streeters themselves, though a lot of producers seem to want to try very hard. Cronenberg's outright refusal to negotiate with realism, his fervent imagination, may be the more appropriate impulse. To get to the heart of a spectacle, sometimes, requires more spectacle.

No comments:

Post a Comment