In a nutshell, he is applying some of the principles of evolutionary biology to cultural evolution.

Here is a little bit from the beginning.

And here are some of what I consider the important ideas from this article.Evolution

At the Institute for the Future's 2011 Ten Year Forecast event in late March, I presented a long talk on ways in which evolutionary and ecological metaphors could inform our understanding of systemic change. The head of the Ten Year Forecast team, IFTF Distinguished Fellow Kathi Vian, thought that the ideas it contained should get a wider viewing, and asked me to put the talk on my blog. Here it is. It's lightly edited, and only contains a fraction of the slides I used; let me know what you think.

We’ve now reached the part of the day where I’ve been asked to make your brains hurt. Don’t worry, there will be alcohol afterwards.

The first thing I’m going to do, of course, is talk about dinosaurs.

Everybody knows about dinosaurs, right? Giant, lumbering lizards that were killed off by an asteroid just when the smarter, more nimble mammals were starting to take over anyway. And everyone knows what dinosaur means as a metaphor: big, stupid, and about to be wiped out. Nobody wants to be a dinosaur.

What if I told you that all of that – all of it – was wrong?

Here’s another dinosaur:

It turns out that most dinosaurs were actually pretty small and fast, and far more closely related to today’s birds than to lizards.

Some dinosaurs we might envision as scaly monsters from the movies were likely actually feathered. It’s widely accepted, in fact, that dinosaurs didn’t all die off when that asteroid struck 65.5 million years ago — they stuck around as birds.

Oh, and one other thing.

The “age of dinosaurs” lasted 185 million years, not counting the 65 million years of dino-birds. And mammals first emerged about halfway through the “age of dinosaurs,” and were stuck scurrying around between dinosaur legs, trying to avoid being eaten.

Dinosaurs have been around, including as birds, for 250 million years. Humans, conversely, have been around in a form recognizable as Homo sapiens for only about 250 thousand years. Dinosaurs have had a thousand times more history than has Homo sapiens.

And they survived – arguably eventually thrived after – one of the biggest mass extinctions in Earth’s history. Maybe being a dinosaur wouldn’t be such a bad thing.

The story of dinosaurs is a particularly vivid example of what happens after complex systems face traumatic shocks. It’s a story of change and adaptation. And it’s one that we can learn from.

This will come as a surprise to precisely none of you, but one of the areas that I studied academically was evolutionary biology. Although I didn’t follow that path professionally, I’ve always kept my eyes open for ways in which bioscience can illuminate dilemmas we face in other areas.There’s one concept from biology that I’ve been mulling for awhile, and I think it has quite a bit to say about our current global situation.

It’s an element of the concept of “ecological succession,” the term for how ecosystems respond to disruptive change. A fundamental part of that process is the “r/K selection model,” with a little r and a big K, which is a way of thinking about the reproductive strategy that living species employ within a changing environment.

Biologist E.O. Wilson came up with this concept over 30 years ago, and it’s proven to be a useful lens through which to understand ecosystems.

* * * * * * *

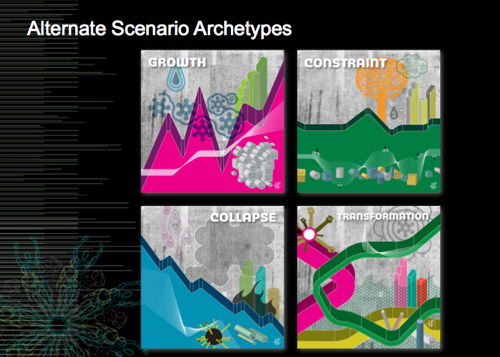

At last year’s Ten-Year Forecast, we introduced a tool for examining how choices vary under different conditions. It’s the “alternate scenario archetype” approach, and it offers us a framework here for teasing apart the implications of different adaptive strategies. If you were here last year, you’ll recall that the four archetypes are Growth, Constraint, Collapse, and Transformation. These four archetypes give us a basic framework to understand the different paths the future might take.

But let’s also apply the ecosystem thinking I was talking about earlier. With this in mind, we can see Growth and Collapse as aspects of the standard ecological succession model: Growth supports K strategy dominance, until we get a major disruption leading to Collapse, which supports r strategy dominance until we return to Growth. As it happens, while they may not use this exact language, many of the long-term cycle theories in economist-land map to this model.

Constraint and Transformation, however, seem more like unstable instability scenarios.

Both Constraint and Transformation have quite a bit in common. Both can be seen as being on the precipice of either growth or collapse, and needing just the right push to head down one path or the other. At the same time, both will contain pockets of growth and collapse, side by side, emerging and disappearing quickly. In both, previously well-understood processes no longer seem to work as well, yet there’s enough that remains functional and understandable that the world doesn’t simply spin apart. For both, the underlying systems are in flux.

With Constraint, the result is a reduced set of options. The uncertainty and churn limit what you can do.

With Transformation, the result is the emergence of new models and new opportunities.

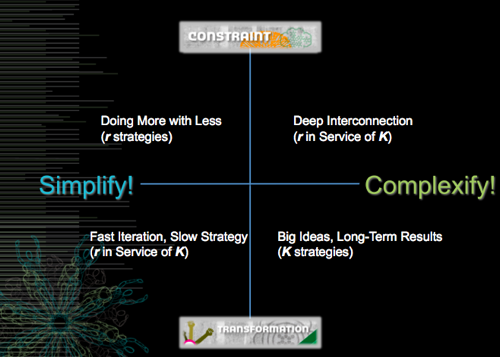

So we have two adaptive strategies – simplify and complexify – and two conditions of “unstable instability” – constraint and transformation. What do you do when you have two variables? You make a matrix!

Ah, the good old two-by-two matrix. So let’s put up the conditions, and the strategies. What happens when we combine them?

In many ways, Constraint and Simplification go hand-in-hand, giving us a world of doing more with less. Smaller scale, fewer resources, and a need for cheap experimentation: this is very much an “r” world.

Similarly, Transformation and Complexification are also common partners, resulting in a world focused on big ideas and long-term results. The potential is here for major changes, but failures can be catastrophic: it’s a classic “K” world.

The less-common combinations, however, prove pretty interesting.

When you link Constraint and Complexification , you get a world of deep interconnection: lots of small components in dense networks. There’s quite a bit of interdependence, but no one element is a potential “single point of failure.” This is an “r in service of K” world.

And when Transformation and Simplification come together , you get a world of fast iteration and slow strategy: numerous projects and experiments functioning independently, with loose connections but a long-range perspective. This, too, is an “r in service of K” world.

Okay.

Remember, I said earlier that foresight relies on intensely metaphorical language. You might not have expected the metaphors to be quite that intense, however. So here’s the takeaway:

Adaptation can take multiple forms, but more importantly, the value of an adaptation depends upon the conditions in which it is tried. Just because an adaptive process worked in the past doesn’t mean that it will be just as effective next time. But there are larger patterns at work, too. If you can see them early enough, you can shape your adaptive strategies in ways that take advantage of conditions, rather than struggle against them.

But here’s the crucial element: it looks very likely that we’re in a period where the large patterns we’ve seen before aren’t working right.

Instead, we’re in an environment that will force swift and sometimes frightening evolution. Businesses, communities, social institutions of all kinds, will find themselves facing a need to simultaneously experiment rapidly and keep hold of a longer-term perspective. You simply can’t expect that the world to which you’ve become adapted will look in any way the same – economically, environmentally, politically – in another decade.

As a result, you simply can’t expect that you will look in any way the same, either.

No comments:

Post a Comment