This is a rarity - I'm posting this article without having read it (because I have not seen the film yet, and I am assuming there are probably spoilers here). So I hope it's good - generally, RAM is someone I mostly agree with, which is why I feel it safe to post without reading.

To really grasp the essence of a dream, we have to approach it with more than our mind, seeking revelation rather than explanation — we must hear it without ears, see it without eyes, know it without thinking, cultivating as much intimacy as possible with both its detailing and its mystery.

And to really grasp the essence of what generates and populates our dreams, we must cease identifying with the us who is apparently dreaming them. This is no small task, yet is within our grasp — which is precisely why Inception pulls at many of us so insistently, eluding our attempts to definitively figure it out. Who — or what — is pulling the strings? When is dreaming happening, and when is it not? And how do we know? More than movie analysis and clever theorizing is required here; if we don’t look deeply into the construction and movement of our own dreams, we won’t get very far in our efforts to make sense out of Inception.

Try to rationally deconstruct Inception, and you’ll find not much more than a superficial satisfaction, for you’ll just be remaining on the surface of the surface, the oh so colorful dramatics and stunning visuals of which can easily keep us tethered to our sensemaking efforts, stranded from the reality-unlocking mystery and ever-present paradoxicalness of what is happening. What’s needed is to slip beneath our cognitive certainties, not back into prerational realms or sensory chaos, but into the eversurprising depths of who and what we truly are.

A tall order? For sure, but what an opportunity! And why not plumb this before we lose ourselves in some sort of limbo? This is the edge with which Inception — or at least our reception to Inception — flirts, behind all the dream-dramatics. Awakening to the fact that we are dreaming — and not necessarily just when we are sleeping — is not the goal of the deepest kind of enquiry, but rather the foundation. There is awakening, and there is a deeper awakening; our work, in part, is to extract the slumber from our I’s, to unmask our implanted certainties, to look inside our looking.

This, of course, is not the stuff of daily life, or even of most spiritual practice, and asks much of us — which we may protest is beyond us — but in our heart of hearts we know better. And a close watching of — and feeling into — Inception serves this psychospiritual plunge/rise/freefall, if only by getting us to question, really question, our conditioned notions about reality and dream-reality.

So Inception is not to be facilely understood or categorized — just like our sleep-time dreams. In fact, it invites, arguably even forces, us to step back a touch from our usual way of understanding, so that we can view our ingrained ways of viewing things, however subtle they may be. We can’t figure out our dreaming consciousness with our everyday cognition; a much deeper, much more inclusive kind of perspective is needed, one that is intimate both with the rationality-centered capacity of our usual mindset and with the metaphorically-centered (and sometimes mystic) capacity of our dreaming consciousness.

Trying to dissect Inception to isolate its core meaning is somewhat akin to cutting open a human brain to find the symphony that its owner created. What is needed is to put away our dissection tools and instruments, and to feel our way in, navigating whatever terrain shows up through an intuitive interplay of touch, feel, visceral insight, and spiritual openness —after all, we are entering deeper and deeper formative levels, with all their attending imagery, intimations, pulls, and populace.

Dreams are the ultimate movies, edited according to what fits us at the moment, presenting a moving picture — do dreams ever really hold still? — that moves us, for better or for worse. Lay awake in a dream, knowing for sure that you are dreaming, and marvel at the 3-D shapeshifting, unspeakably eloquent reality in which you are immersed; one shift in intention, and the whole scene shifts, changes, perhaps even disappears — what a vivid wonder, what wild and sometimes unsettling beauty, more often than not suffused with hyperbole-transcending significance!

When things get very real — like at the truly big moments of our lives — we often say that they feel dreamlike, or that we feel like we are in a dream. Many times, the more real something is, the more dreamlike or at least surreal it often seems. And why? Partially because we may not have adjusted to our new situation, but primarily because reality at essence is, in its form, as malleable and transparent and — especially — paradoxical as a dream. A key question at such times is: Who or what is doing the dreaming? If we say “the dreamer,” we are still on the outside, just like a casual viewer of Inception. But sufficiently penetrate the self-presentation of the apparent dreamer, and a startlingly significant discovery is made: the dreamer is actually just another part of the dream, as mechanically constructed as the other elements of the dream.

The “I” of our dream may seem to stand out, to be apart from the rest of the dream, but this does not mean that it actually is, any more than our waking-state egoity is really the operational hub of our being. Decentraliziing our egoity allows our real individuality to more clearly emerge, and the same is true of our dreams — decentralize the “I” who is starring in your dream, and a deeper sense of individuality emerges, who recognizes himself or herself in every part of the dream. Cobb, the protagonist of Inception, does not take this step, keeping himself bound up in his everyday identity, even though he recognizes many of his dream-beings as projections of different aspects of his personal history. Almost all of the others he meets in his dream theatrics are taken to be discrete individuals, as real as the most solid of objects in waking-state reality. An exception? His wife — but he is so obsessed with keeping her alive in his deepest recesses, to having her be more than a dream, that he dreams her into a realism that makes her just as substantial as him, preferring being in a kind of limbo with her to waking up from the dramatics in which he is submerged. And Cobb, having lost control of his everyday life through his wife’s death — being unable to be with his children — is desperate to have some semblance of control, which manifests in his dreaming and efforts to manipulate things through dreaming.

If we have the capacity to control our dreams, at least to some degree, we may delude ourselves into assuming that we are running the show — but the very act of trying to control what happens in our dreams may itself be no more than a playing out of our conditioning, as automatic as anything else in the dream. So what to do? The short answer is: Wake up! But to do so, we have to be intimate with the phenomenon of false awakening, meaning when we dream that we have awakened from our dream, but in fact have not — merely dreaming that we are not dreaming. In Inception, the awakenings are not necessarily true awakenings, but often just view-takings from different floors of the same dream-building, featuring varying degrees of lucidity.

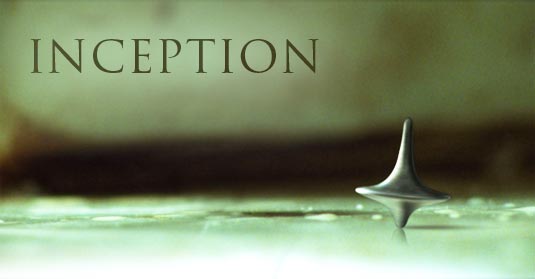

Let’s now consider Cobb’s spinning top token/totem, the whirl and wobble of which is not only ultimately ignored by him — perhaps more unconsciously than deliberately — but also brilliantly ends the film, leaving viewers on paradoxical ground, glimpsing the whirl and wobble of their own minds for a few wonderfully disorienting moments, in the uncertainty of which shines an opportunity to awaken beyond their psychosocial corralings. In the practice of lucid dreaming (dreams in which we know that we are dreaming) we may employ certain things to remind us that we are indeed dreaming; we may set atwirl a top that doesn’t stop spinning, we may look in a book and see constantly moving letters, we may flick on light switches that don’t work, we may touch a wall and have our hand pass through it, or we may levitate — whatever unequivocally indicates to us that we are indeed in a sleep-dream.

But what if our reality check doesn’t work? Does this necessarily mean that we are not dreaming? No, for we could be dreaming that our reality check is not working. At the end of the film, we may take the apparent fact that the top keeps spinning as a sign that Cobb is still dreaming, but we could also take the very same fact as a sign that the viewer of the whole scene — us — is doing the dreaming. That is, Cobb is then not so much dreaming as being dreamt by an unseen entity, an offscreen observer or locus of observation. Then we might ask: Are we, like Cobb, in a dream that is so all-encompassing, so powerfully engrossing, so emotionally compelling, that we don't know it is a dream? Is Cobb’s interiority — and he is the only character in the film whose inner workings are revealed in any telling detail — touching our own, especially the psychological layerings that are dramatized in our own dreams?

Such questions are not meant to tie our minds in knots or lock us up in dead-end abstraction, but to stop our discursive mentalizing in its tracks, so that our deeper capacity to see can emerge relatively unhindered. Is Cobb really reunited with his children? Or is his fantasy of being thus reunited so strong, so compelling, that he is sure that he is truly with them? After all, dreams, as we all know, can be extremely convincing, even when their elements are patently absurd or impossible.

And what a seductive dream it is to believe that we can control our dreams so thoroughly and precisely! As if psychoemotional dynamite from our past can be shunted away from us or defused simply through our intention that it behave thus! The everwild Mystery of Being is not so easily corralled or controlled, for it includes and enfolds us, rather than being contained by us. In Inception the fantasy of being able to control our deep interiority and primal wounding is given powerful dramatic expression, being shown to be not much more than a compensatory result and denial of not being in control the way we’d like to be. And we the viewers, with not so many exceptions, also want to have the control to be able to neatly categorize the movie, to somehow tuck it away in our files of the understood. Kudos to director Christopher Nolan for not letting us get away with this!

If you find yourself in a dream while knowing you are dreaming, and the dreamscape is stable enough to last for a while, take a very close look at what is before you — and you will almost invariably see an incredible complexity and detailing, imbued with riveting significance, all arising in a space that is none other than your bare consciousness. For Cobb, this space is so crammed with drama and tremendously compelling self-concern that it goes unnoticed; he doesn’t recognize that he is arising in this space, this raw openness, populating it with whatever fits the storyline about which his life revolves. He keeps spinning around what he has created, spinning and spinning, becoming his own token, losing sight of what he is actually doing, seeding himself with the intent to stay on course, even when he dreams otherwise. Just like us, so much of the time, perhaps even now...

Copyright © 2010 by Robert Augustus Masters

Tags:

1 comment:

Fantastic movie for a mainstream Hollywood fare. You've gotta see it, Bill. The review above struck me as a bit on the pretentious and condescending side, like the sermon of a minister who takes a Bible story about Joseph and his brothers and says, "Now let me talk about lucid dreaming for half an hour..."

Post a Comment