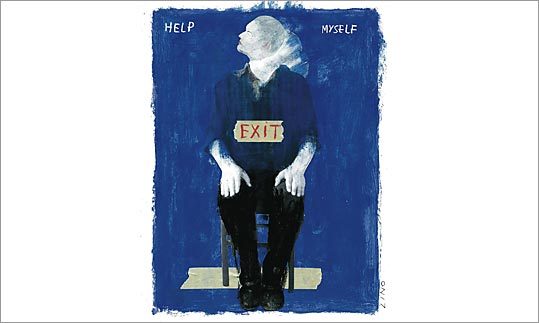

The Boston Globe ran an interesting story the other day about the effort to pin down just when someone is suicidal or not. A tough task, especially give that the assessment tool (the IAT) is an imperfect thing. The article does raise questions of efficacy and is well-written and researched.

The Boston Globe ran an interesting story the other day about the effort to pin down just when someone is suicidal or not. A tough task, especially give that the assessment tool (the IAT) is an imperfect thing. The article does raise questions of efficacy and is well-written and researched.On the EdgeRead the rest of the article.

Can a test reveal if a person has a subconscious desire to kill himself? Peter Bebergal, who lost a brother to suicide, goes inside Mass. General, where Harvard researchers are trying to find out.

By Peter BebergalOn June 12, 2004, my brother Eric was admitted to the emergency room at Mass. General Hospital, unconscious after what appeared to be a failed suicide attempt. His wife, Cheryl, had found him passed out near the floor of their bedroom closet, a wire wrapped around his neck and attached to the closet pole. Had she gotten home any later, he might not have been alive. I arrived at the hospital a few hours after he had been brought in, joining Cheryl and my oldest sister, Lisa. The police interviewed us, and we all agreed that the past few months had been tumultuous: fights, restraining orders, drinking, and severe depression. Eric was kept in intensive care and, according to the police report, was in "stable and improving condition." He was released the next day.

A few weeks later, after Eric had agreed to go into an outpatient program but failed to show up for any appointments, he was found in his Winthrop apartment, slouched over on his knees. He had choked himself to death with a wire attached to a closet pole. He was 46.

As most clinicians would agree, one of the most heartbreaking aspects of psychiatric emergency work is the suicidal patient. When assessing a person's risk for suicide, ER doctors have little to work with. Unless the patient has a medical history that includes other suicide attempts, clinicians rely heavily on their evaluative skills and what is called the self-report, the patient's own appraisal of what happened and how the person is feeling. Was the overdose accidental or intentional? Had he or she been drinking? Did the person stop taking any prescribed medication? Did he really want to die when he strung up a wire in the closet and wrapped it around his neck, or was that a cry for help?

Eric's self-report became an important factor in deciding what to do. But my brother had worked in healthcare for many years and had a sense of what to say and how to act. What he wanted was to go home. But should he have been admitted involuntarily to the inpatient psychiatric unit instead? Weren't the circumstances of what brought him into the hospital in the first place reason enough to suspect he was seriously ill?

In Massachusetts, if a patient clearly demonstrates imminent risk, he can be involuntarily admitted for up to four days, at which point a court hearing determines whether to extend the stay. But those admissions are rare. Lanny Berman, executive director of the American Association of Suicidology, explains that unless you are actually threatening to kill yourself while in the hospital, it is highly unlikely that you will be admitted for any length of time. This is mainly because it is extremely difficult to assess suicidality in patients. For one thing, many people who are suicidal have good reason not to let on that they are a danger to themselves: They want to die.

What clinicians need is some other measure beyond external evidence that could assess whether someone like Eric is capable of suicide in the near future. Four years after my brother's death, Harvard researchers at MGH are experimenting with a test they think could help clinicians determine just that. It focuses on a patient's subconscious thoughts, and if it can be perfected, these researchers say it could give hospitals more of a legal basis for admitting suicidal patients.

Of course, I can't help thinking about whether such a test could have saved my brother. But I also wonder: Would it have been ethically right - or even possible - to save him even if he didn't want to save himself?

THIS MISSING PIECE in the suicidal puzzle is what prompted the innovative research study now in its final phase at MGH. The study, led by Dr. Matthew Nock, an associate professor in the psychology department at Harvard University, is called the Suicide Implicit Association Test. It's a variation of the Implicit Association Test, or IAT, which was invented by Anthony Greenwald at the University of Washington and "co-developed" by Dr. Mahzarin Banaji, now a psychology professor at Harvard who works a few floors above Nock on campus. The premise is that test takers, by associating positive and negative words with certain images (or words) - for example, connecting the word "wonderful" with a grouping that contains the word "good" and a picture of a EuropeanAmerican - reveal their unconscious, or implicit, thoughts. The critical factor in the test is not the associations themselves, but the relative speed at which those connections are made. (If you're curious, take a sample IAT test online at implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/.)

The IAT itself is not new - it was created in 1998 - and has been used to evaluate unconscious bias against African-Americans, Arabs, fat people, and Judaism. But critics question whether the test is actually practical, and up until now no one has tried to apply it to suicide prevention. As part of his training, Nock worked extensively with adolescent self-injurers - self-injury, such as cutting and burning, is an important coping method for those who engage in it, though they are often unlikely to acknowledge it. Nock thought that the IAT could serve as a behavioral measure of who is a self-injurer and whether such a person was in danger of continuing the behavior, even after treatment. In their first major study, Nock and Banaji asserted that the IAT could be adapted to show who was inclined to be self-injurious and who was not. And more important, they said, the test could reveal who was in danger of future self-injury.

The next step, Nock realized, was to use the test to determine, from a person's implicit thoughts, whether someone who had prior suicidal behavior was likely to continue to be suicidal. It would give doctors a third component, along with self-reporting and clinician reporting, and result in a more complete picture of a patient. Nock doesn't assume that a test like the IAT would be 100 percent accurate, but he believes it would have predictive ability. "It is not a lie detector," he says. "But in an ideal situation, a clinician who is struggling with a decision to admit a potentially suicidal patient to the hospital, or with an equally difficult decision to discharge a patient from the hospital following a potentially lethal suicide attempt, the IAT could provide additional information about whether the clinician should admit or keep that patient in the hospital."

Over two years, researchers at MGH asked patients who had attempted suicide if they would be willing to participate in the test. About two-thirds of them agreed (some 200 patients) - even though some had tried killing themselves just hours before - and after answering a battery of questions about their thoughts, sat with a laptop and took the IAT.

During one test, a person was shown two sets of words on a screen, one in the upper left corner, one in the upper right. A single word then appeared in the center, and the test taker was asked to indicate with a keystroke the corner containing the word that connected to the center word. The corner sets were drawn from two groups of words (one group was "escape" and "stay," and another was "me" and "not me"). In one version, the sets were "escape/not me" and "stay/me," and the series of words that appeared in the center included, among others, "quit," "persist," "myself," and "them." The correct answers called for "quit" to be associated with the side that had "escape," for "myself" to be matched with the side that had "me," and so forth. In theory, a delay in answering on "quit," even if the person got it right, could reveal that he was associating the idea of "quit" with the idea of himself. The word sets varied depending on the test, and bias could emerge in a positive or negative way. For example, if the sets were "escape/me" and "stay/not me" and a person hesitated in correctly matching "myself" to the side with "me," it could reveal that he was associating himself with the idea of "stay."

For about the next five months, Nock and his research team at Harvard will analyze all the data collected from MGH. If they think their findings show promise, they will follow up and run their experiment again to see if it yields similar results. If it does, they may seek to implement the test at an area hospital. For now, following up with patients will be pivotal in assessing the test's effectiveness. Tragically, though, the only way researchers will know for sure whether the test can predict behavior is if a key number of patients attempt suicide again.

I have no doubt that the IAT can be a useful tool, but its limitations were pointed out in a study that I posted a few days ago about narcissists. Anyone with the slightest grasp on reality (and most suicidal people are not psychotic) can give answers that will jack the test and get them released, just as happened with the author's brother in this article.

On the other hand, if it saves just ONE life that otherwise would have been lost, then it should be used until some better assessment tool becomes available.

Still, the article goes on to raise some serious efficacy and ethics issues about the test:

The test also raises an ethical issue. Could the IAT have other, Big Brother-type uses that might give those in authority too much of a view into our thought-lives? For example, could something like the IAT be given to a prisoner before a parole board to assess whether he or she would be likely to commit another crime? Nock believes that if the test proves to be accurate, then yes, it would be appropriate to use when making certain determinations. In the case of suicidal patients, he says, if the test is 100 percent accurate, then it should weigh "very heavily" in deciding if someone should remain in the hospital. If it proves to be 75 percent accurate, he adds, then it should not override other evidence.

Dr. Leon Eisenberg, professor of social medicine and professor of psychiatry emeritus at Harvard, agrees that on the surface there is something troubling about the idea that what he calls the "last bastion of privacy" could be tampered with. But on the other hand, he sees the IAT as modest in its tinkering with unconscious thoughts. And he adds that "most doctors, most laws, and most policemen think preventing suicide is a legitimate state function."

Another issue is simply whether the test can actually be useful in the context of the emergency room. In the fit of a depressive episode or under the influence of drugs and alcohol, a person who might try to kill himself might otherwise not harbor suicidal thoughts. Nock says that suicidal thoughts and behaviors can be remarkably transient. In some cases, he says, a person might feel suicidal at one moment, but after a failed attempt is happy to still be alive and no longer wants to die. Nevertheless, Thomas Joiner, author of the 2005 book Why People Die by Suicide, believes that those who are most at risk are likely to tell a clinician they are suicidal. While he thinks the IAT could be an important evaluative tool, he wonders if using the test in what will already be a challenging clinical setting might be a distraction.

Nock agrees but points to a troubling statistic from a 2003 study: More than 70 percent of the people who died by suicide had said in their final communication to another person that they were not a danger to themselves. "We cannot rely on a person's self-report alone, as doing so will certainly lead us to miss many, many opportunities to prevent suicide deaths," he says. Nock wants only to be able to fill in the gaps of what is now a tricky part of psychiatric work. Still, for those who want to die, a test like the IAT will only further reveal what their private intent is. How then can clinicians and researchers go from test to treatment? How could knowing that my brother wanted to die the night he was released help experts show him his life could have meaning?

Go read the whole article.

Tags:

No comments:

Post a Comment