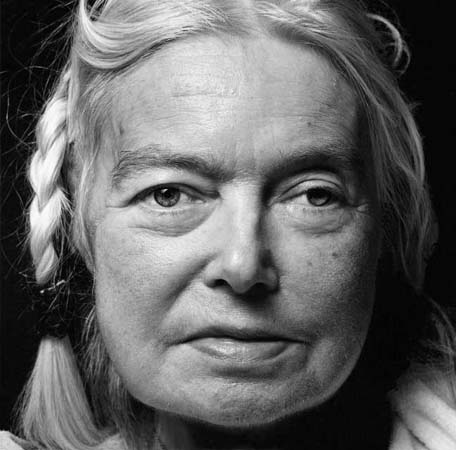

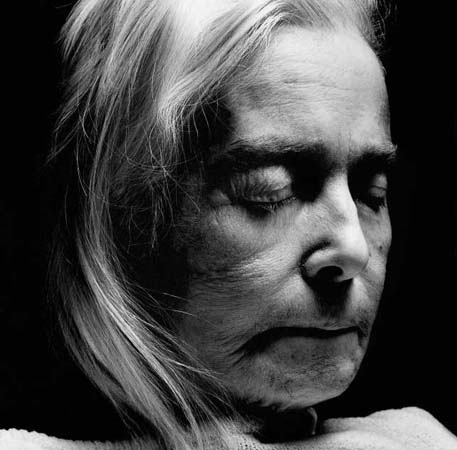

This sombre series of portraits taken of people before and after they had died is a challenging and poignant study. The work by German photographer Walter Schels and his partner Beate Lakotta, who recorded interviews with the subjects in their final days, reveals much about dying - and living. Life Before Death is at the Wellcome Collection from April 9-May 18.

Joanna Moorhead writes about the exhibit and its genesis.

Nothing, it is said, teaches us more about living than dying. But if so, isn't it odd how little we face up to death? And isn't it odd that modern societies, which appear so keen to find meaning in the business of living, push death to the periphery, minimising our contact with it and sanitising its impact?The German photographer Walter Schels thinks it not only odd, but wrong that death is so hidden from view. Aged 72, he's also keenly aware that his own death is getting closer. Which is why, a few years ago, he embarked on a bizarre project. He decided to shoot a series of portraits of people both before and after they had died. The result is a collection of photographs of 24 people - ranging from a baby of 17 months to a man of 83 - that goes on show in London next week. Alongside the portraits are the stories of the individuals concerned, penned by Beate Lakotta, Schels' partner, who spent time with the subjects in their final days and who listened as they told her how it felt to be nearing the end of their lives.

Read the whole article.

One of the cool things at the museum's website is a link to The Lancet (free registration required), where you can find a collection of lengthy articles on death as seen from the world's major religious traditions, including Buddhism. This article (like all of those in this series) is largely written to assist doctors in being more understanding of cultural needs around death, which is certainly to be applauded. Here is a just a single paragraph.

According to Buddhist teachings, a life in any one existence begins at conception and ends at death: in the interval between these events, the individual is entitled to full moral respect, regardless of the stage of psychophysical development attained or the mental capacities enjoyed. According to the most ancient authorities, death occurs when the body is bereft of three things: vitality (ayu), heat (usma), and sentiency (viññana). The problem for contemporary Buddhists is to express these three traditional indicators in terms of the concepts of modern medical science—eg, do they correspond to the modern standard of brain death? Although heat is straightforward, the other two indicators pose hermeneutical problems that make a simple resolution of the question difficult.1 It is interesting that the ancient scriptures record that when the Buddha died, he was at first mispronounced dead by his attendant of 25 years, Ananda. Ananda was then corrected by a senior monk who stated that the Buddha had simply entered a profound state of yogic trance in which no vital signs can be discerned. If such physiological states do exist, and they are well attested in Buddhist literature, then the scope for error in determining death is clearly increased. Therefore, opinion among Buddhists is divided. Some think that brain death correlates with the ancient criteria whereas others do not.1

Here is just one set of the photos -- you can view many more here.

Buddhism teaches us to befriend our death, the shadow that is always walking with us through life, just out of sight. Death is not to be feared, but to be embraced as the ultimate reminder that all things are impermanent, and that attachment, even to this precious life, is painful.

I am struck, as I have always been, by the sense of peace of the faces of the dead (barring traumatic deaths, which may disfigure the face). I see that same feeling in these photos, including the ones above.

No comments:

Post a Comment