This is a very cool article in which philosopher Alva Noë looks at one of my favorite films through a perspective I have never taken or even considered - the film is about the act of coming to realize that something is wrong. It's clear something is wrong long before Rosemary is able to accept that the people she trusts are not who they say they are.

And that realization brings in the more important theme of "can we ever truly know another person?" In essence, this is about theory of mind. Except that here, as in reality, we know that others have an interior world to which we are not privy, we "can't get inside their heads to learn what they really think and feel. We are always at a remove from the other."

This article comes from NPR's 13.7 Cosmos and Culture blog.

'Rosemary's Baby' Thrills With Unfathomable Mystery

by ALVA NOË | June 07, 2014

I watched Rosemary's Baby, by Roman Polanksi, again last night. It is a monster movie. And like the best movies in this genre, you could call it a skepticism movie. It is philosophical. And, remarkably, it is terrifying because it is philosophical.

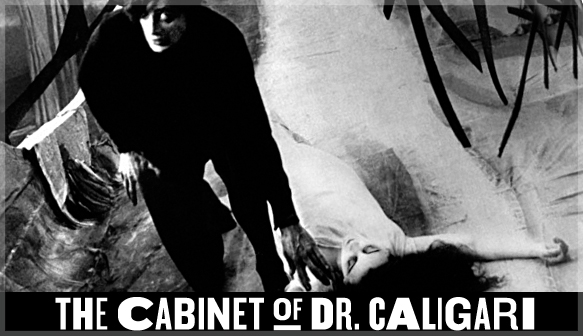

Mia Farrow in Rosemary's Baby. The Kobal Collection/Paramount

Things aren't going right with young Rosemary. Her husband is distant, removed, self-centered; he is unkind and even brutal with her; he spends his free time with their new neighbors, an odd, elderly couple next door. Rosemary's pregnancy is difficult; she has pains continually and is losing weight; neither her doctor nor her husband seem to be interested in helping. Rosemary is in a stupor, as if she were under the influence of drugs.

She has their new apartment painted brightly to lighten it up. But this does little to dispel the dark in its halls and rooms. The only bright spot in this dim scenario is that Guy, who is an actor, has had a turn of good luck at work. His rival woke up blind and Guy got the big part. Professional success is around the corner.

Rosemary's Baby is a story about coming to recognize that something is wrong. At first Rosemary resists this conclusion. What could be wrong? Occasionally pregnancies are painful. Husbands get caught up with pressures and demands at work. Life isn't supposed to play out like a fairy tale. She resolves herself to be a better wife, to reach out to Guy and help him be more open in their relationship.

Now the character of the movie's skepticism shifts to one of philosophy's enduring skeptical concerns: the very possibility of knowing other people and what they think and feel.

Philosophers have long noticed that that there is room for doubt in this domain: all we ever really know, when it comes to others, is what they say and do. We can't get inside their heads to learn what they really think and feel. We are always at a remove from the other. It is also clear, to philosophy and to us all, that this intellectual worry can be safely set aside in the course of our ordinary lives. Questions about what those around us are thinking and feeling and doing, let alone questions about whether they have inner lives at all, don't seriously arise. Which itself raises a philosophical question: if the basis of our knowledge is so sleight, why is our confidence in other minds so robust? (I explore this in my book Out of Our Heads: Why You Are Not Your Brain, and Other Lessons from the Biology of Consciousness.)

Sometimes these sorts of theoretical worries achieve practical prominence in the setting of neurological trauma when we are confronted by, for example, persistent vegetative state, and must make decisions about what is going on inside the mind of an badly injured person.

But Rosemary's Baby addresses these questions in, what, if possible, is an even more terrifying way. It gradually becomes clear, to Rosemary, and to us, the audience, that we can no longer trust Guy, or the neighbors, or the doctor, or just about anyone else in Rosemary's life. Skepticism about the thoughts and feelings of those around Rosemary is now a hypothesis that must be taken seriously. Her life, and that of her baby, depends on it. She is the victim, it seems, of an elaborate plot. And (almost everyone), even those most close to her, is in on it.

Is this not madness? It certainly has that look and feel. How could everyone be in on it? This, then, ratchets the movie's skeptical theme up a notch: could it be that she is hallucinating or confabulating the whole thing? Could this be some sort of pre-partem hysteria? Can she, do we, know what is real?

But Rosemary's Baby is not just a psychological thriller. It is a monster movie. And what makes Rosemary's predicament so very difficult is the fact that what is really going on, so we come to believe, what is really driving events in this film, is so unlikely, so impossible, so unthinkable, as to rule out the possibility of anything like a straight forward "figuring out" of what's happening.

Satan himself has come to Earth and raped Rosemary, with the assistance of her husband and almost everyone else she knows. This is too far-fetched to be true. It is too far-fetched to be even thinkable.

The distinctive charms and fascinations of horror films arise at this kind of juncture, according to the noted philosopher of art Noël Carroll. It is the hallmark of all narrative forms they they supply us with cognitive delights. Plot intrigues; we are curious; curiosity motivates us to follow the story, to figure out what's going on, to understand how forces at play in a situation drive the action inexorably forward. Plot is cognitive and the pleasure of story arises from the achievement getting it.

I think Carroll is right about this. The basic idea was anticipated already in Aristotle's treatment of tragedy. Plot, Aristotle argued, is the life and soul of tragedy. And plot is concerned not with mere event, not with one thing happening after another. But with human action. So to tell a good story, or to enjoy one in the audience, you need to be sensitive to what makes an action significant in the setting of a human life. You need to be a student of human nature and experience.

It is because the meaning and importance of a work of dramatic fiction comes in the exploration of ideas about human experience that it is possible to enjoy a play just by reading it. It isn't spectacle that moves us; for Aristotle, it's understanding. Which doesn't mean that one does not also enjoy felt or emotional responses to the story. A tragedy, Aristotle thought, always aims to arouse fear and pity. But it doesn't aim to produce emotion the way a ride on a roller coaster produces a sense of danger. Fear is not merely an effect on us or in us. It is an expression of our sensitivity to what is playing out in the story and so it is itself an achievement of understanding and insight.

Now the distinctive difference between horror and other genres — this is Carroll's argument — is that the heart of the horror genre is a monstrous phenomenon that actually, truly, makes no sense. Monsters are unfathomable. They are unknowable. They are betwixt and between. Neither alive nor dead, neither human or animal, neither natural nor, really, unnatural. They are, as Carroll puts it, interstitial. The point is that there is no understanding of the monstrous. There is no genuine satisfaction of our curiosity.

A good horror movie, I would say, then, is a kind of paradox in itself. It engages you in a mystery whose intrinsic character rules out, or threatens to rule out, its resolution. And it is the distinct feature of art horror — as opposed to what might horrify us in real life — that it affords the opportunity for philosophical engagement with the unresolvable. From this point of view, the fact that we find the monster scary is secondary. We don't like horror movies because we like to feel negative emotions. It is, rather, that the negative emotions are outweighed by the philosophical delights.

I'm not sure whether this account does justice to Rosemary's Baby. Perhaps its real fright stems from its suggestion that the philosopher's unresolved skeptical puzzles about the limits of knowledge of others and the world around us reveal the underlying reality of our condition, the fact of our total, absolute, abject, terrifying isolation. But is that something we take pleasure in discovering?

~ You can keep up with more of what Alva Noë is thinking on Facebook and on Twitter: @alvanoe.

%205.jpg)