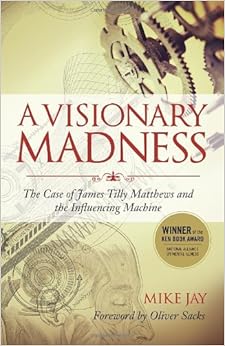

Mike Jay is the author of A Visionary Madness: The Case of James Tilly Matthews and the Influencing Machine (2003/2014), an in-depth case study of one of the first and best documented cases of what the Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM) would eventually name paranoid schizophrenia.

[NOTE: This post goes with an earlier post of a BBC documentary on the history of "madhouses" that appeared here earlier today.]

Here is the ad copy for the book from Amazon:

Confined in Bedlam in 1797 as an incurable lunatic, James Tilly Matthews is one of the most bizarre case studies in the annals of psychiatry. Often cited as the first thorough case study of what we would today call paranoid schizophrenia, Matthews drew intricate diagrams of the "influencing machine" that he believed to be reading and controlling his mind. But his case was even stranger than his doctors realized: many of the incredible conspiracies in which he claimed to be involved were entirely real.Matthews had believed he was brokering a peace treaty between England and France, and went to France in 1793, but the Girondists he was speaking with were removed and frequently executed by the Jacobins. Matthews quickly fell under suspicion for his Girondist associations and was suspected of being a double agent.

A Visionary Madness traces the story of antiwar advocate James Tilly Matthews through the political and social upheaval of the late eighteenth century, providing a vivid account of the unraveling of Matthews's mind, a snapshot of late eighteenth-century psychiatry, and its relevance to current narratives of madness, conspiracy theories, mind control, and political manipulation. Digging deep into historical records and primary sources, author Mike Jay carefully untangles truth from delusion, providing evidence that Matthews was a political prisoner as much as a madman: he had been working as a double agent in the French Revolution and was privy to political secrets the British government feared he might expose. In the process, Jay illuminates the murky revolutionary politics of the 1790s and situates Matthews' visionary madness within the wider cultural upheavals of a world on the brink of modernity. The details of Matthews' treatment in Bedlam reveals the birth-pangs of early psychiatry and its struggle to free its patients from the harsh regimes of the eighteenth-century madhouse. A fascinating and fast-paced narrative history, A Visionary Madness raises profound questions about the nature of madness and the birth of the modern world.

Matthews suffered three years of confinement in France following the Jacobin coup d'etat (during what would later be known as "The Reign of Terror"). The French released him in 1796 believing him to be a harmless lunatic. By the point, after three years of nearly constant pleading for his release, which was generally met by silence, he was well on his way to losing his mind (and in fact, it was during this confinement that the first obvious symptoms began to appear).

When he returned to England in 1796, he was locked up in Bethlem Hospital, commonly known as Bedlam, after disrupting a debate in the House of Commons. He was committed as an incurable "lunatic."

Not long after his admission, and as part of a review process in which he sought his release, Matthews became forever entwined with Dr. John Haslam, a physician with an interest in the "insane," and a younger man with a lot of ambition. After the hearing for Matthews' release ended, Haslam saw in his patient a unique opportunity for a case study.

In 1810, Haslam produced the book, Illustrations of Madness (original title: Illustrations of Madness: Exhibiting a Singular Case of Insanity, And a No Less Remarkable Difference in Medical Opinions: Developing the Nature of An Assailment, And the Manner of Working Events; with a Description of Tortures Experienced by Bomb-Bursting, Lobster-Cracking and Lengthening the Brain. Embellished with a Curious Plate." Haslam's book grew out of the release hearing and from his need to dispute the two doctors who testified to Matthews' sanity. The book contains verbatim accounts of Matthew's beliefs and hallucinatory experiences and is the first full study of a single psychiatric patient in medical history.

The special brilliance of this book is that Jay, more than 300 years after the events described took place, is able to contextualize Matthews' life and experience in such a way that we can see how the events he lived through helped shape and define his particular and unique form of mental illness. For those of us who work in the field, the way we understand psychosis could be completely reframed by this book.

It becomes clear as we read that psychosis is not random, is not purely organic (genetics), and is not lacking an internal logic. Matthews was "driven crazy" by circumstances and temperament, and even in the depths of paranoid delusions about "influencing machines," he comes across as rational and lacks the thought disorder characteristic of schizophrenia. After all, he was able to convince family and friends, as well as the two doctors who testified that he was completely sane.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this case study is that it marks a transition in how mental illness is experienced by the individual. Until this case, most if not all records of psychosis involve influence and control by God, demons, spirits, and other supernatural forces. But Matthews, and millions of people after him, there is now the influencing machine. The rise of science in the Enlightenment created a new source for fear and paranoia - technology.

Jay does a remarkable job of explicating the "air loom" that Matthews believed was controlling him and many other people (if not all people). Here is a brief description of the "air loom" from Wikipedia:

Matthews believed that a gang of criminals and spies skilled in pneumatic chemistry had taken up residence at London Wall in Moorfields (close to Bethlem) and were tormenting him by means of rays emitted by a machine called the "Air Loom". The torments induced by the rays included "Lobster-cracking", during which the circulation of the blood was prevented by a magnetic field; "Stomach-skinning"; and "Apoplexy-working with the nutmeg grater" which involved the introduction of fluids into the skull. His persecutors bore such names as "the Middleman" (who operated the Air Loom), "the Glove Woman" and "Sir Archy" (who acted as "repeaters" or "active worriers" to enhance Matthews' torment or record the machine's activities) and their leader, a man called "Bill, or the King".Here is Matthews' incredibly detailed illustration of the "air loom":

Matthews' delusions had a definite political slant: he claimed that the purpose of this gang was espionage, and that there were many other such gangs armed with Air Looms all over London, using "pneumatic practitioners" to "premagnetize" potential victims with "volatile magnetic fluid". According to Matthews, their chief targets (apart from himself) were leading government figures. By means of their "rays" they could influence ministers' thoughts and read their minds. Matthews declared that William Pitt was "not half" susceptible to these attacks[3] and held that these gangs were responsible for the British military disasters at Buenos Aires in 1807 and Walcheren in 1809 and also for the Nore Mutiny of 1797.

In 1814 Matthews was moved to "Fox's London House", a private asylum in Hackney, where he became a popular and trusted patient. The asylum's owner, Dr. Fox, regarded him as sane. Matthews assisted with bookkeeping and gardening until his death on 10 January 1815.[4]

Interestingly, in addition to the notes Haslem kept on Matthews, Matthews kept notes of Haslem and how he conducted himself, as well as his treatment in Bethlem. These notes became evidence looked at by a Select Committee of the House of Commons in 1815, following Matthews death. The hearings led to Haslam's dismissal and to reform of the treatment of patients in the Bethlem Hospital.

It's a fascinating and captivating narrative, and it is told without a lot of jargon. This books is highly recommended for therapists and for those who know someone suffering from psychosis.