.

in a book about D.H. Lawrence, while discussing

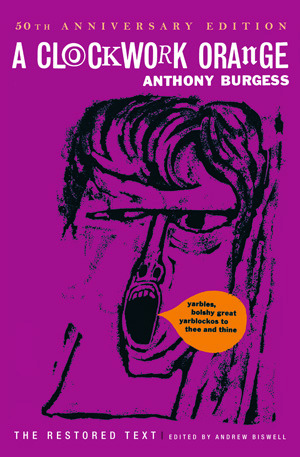

The novel is brilliant, although the American edition was originally published without the crucial final chapter in which Alex realizes he no longer enjoys violence and sets about living a different life.

By MARTIN AMIS

Published: August 31, 2012

The day-to-day business of writing a novel often seems to consist of nothing but decisions — decisions, decisions, decisions. Should this paragraph go here? Or should it go there? Can that chunk of exposition be diversified by dialogue? At what point does this information need to be revealed? Ought I use a different adjective and a different adverb in that sentence? Or no adverb and no adjective? Comma or semicolon? Colon or dash? And so on.

These decisions are minor, clearly enough, and they are processed more or less rationally by the conscious mind. All the major decisions, by contrast, have been reached before you sit down at your desk; and they involve not a moment’s thought. The major decisions are inherent in the original frisson — in the enabling throb or whisper (a whisper that says, Here is a novel you may be able to write). Very mysteriously, it is the unconscious mind that does the heavy lifting. No one knows how it happens.

When, in 1960, Anthony Burgess sat down to write “A Clockwork Orange,” we may be pretty sure that he had a handful of certainties about what lay ahead of him. He knew the novel would be set in the near future (and that it would take the standard science-fictional route, developing, and fiercely exaggerating, current tendencies). He knew his vicious antihero, Alex, would narrate, and that he would do so in an argot or idiolect the world had never heard before (he eventually settled on a blend of Russian, Romany and rhyming slang). He knew it would have something to do with Good and Bad, and Free Will. And he knew, crucially, that Alex would harbor a highly implausible passion: an ecstatic love of classical music.

We see the wayward brilliance of that last decision when we reacquaint ourselves, after half a century, with Burgess’ leering, sneering, sniggering, sniveling young sociopath (a type unimprovably caught by Malcolm McDowell in Stanley Kubrick’s uneven but justly celebrated film). “It wasn’t me, brother, sir” Alex whines at his social worker, who has hurried to the local jailhouse: “Speak up for me, sir, for I’m not so bad.” But Alex is so bad; and he knows it. The opening chapters of “A Clockwork Orange” still deliver the shock of the new: a red streak of gleeful evil.

On a night on the town Alex and his droogs (partners in crime) waylay a schoolmaster, rip up the books he is carrying, strip off his clothes and stomp on his dentures; they rob and belabor a shopkeeper and his wife (“a fair tap with a crowbar”); they give a drunken bum a kicking (“we cracked into him lovely”); and they have a ruck with a rival gang, using the knife, the chain, the straight razor. Next, they steal a car, cursorily savage a courting couple, break into a cottage owned by “another intelligent type bookman type like that we’d fillied with some hours back,” destroy the typescript of his work in progress and gang rape his wife. And all this has been accomplished by the time we reach Page 20.

In a brief hiatus between storms of “ultra-violence,” Alex goes home to Municipal Flatblock 18A. Here, for a change, he does nothing worse than keep his parents awake by playing the multi-speaker stereo in his room, listening to a new violin concerto, before moving on to Mozart and Bach. Burgess evokes Alex’s sensations in a bravura passage that owes less to nadsat, or teenage pidgin, and more to the modulations of “Ulysses”:

“The trombones crunched redgold under my bed, and behind my gulliver the trumpets three-wise silverflamed, and there by the door the timps rolling through my guts and out again crunched like candy thunder. Oh, it was wonder of wonders.”

Here we feel the power of that enabling throb or whisper — the authorial insistence that the Beast would be susceptible to Beauty. At a stroke, and without sentimentality, Alex is realigned. He has now been equipped with a soul, and even a suspicion of innocence. Burgess airs the sinister but not implausible suggestion that Beethoven and Birkenau didn’t merely coexist. They combined and colluded, inspiring mad dreams of supremacism and omnipotence.

In Part 2, violence comes, not from below, but from above: it is the “clean” and focused violence of the state. Having served two years of his sentence, the entirely incorrigible Alex is selected for a crash course of a Reclamation Treatment, a form of aversion therapy. Each morning he is injected with a strong emetic and wheeled into a screening room, where his head is clamped in a brace and his eyes pinned wide open. Alex is then obliged to watch familiar scenes of recreational mayhem, lingering mutilations, Japanese tortures and finally a newsreel, with eagles and swastikas, firing squads, naked corpses. The soundtrack of the last clip is Beethoven’s Fifth. From now on Alex will feel intense nausea, not only when he contemplates violence, but also when he hears Ludwig van and the other starry masters. His soul, such as it was, has been excised.

We now embark on the curious apologetics of Part 3. “Nothing odd will do long,” said Dr. Johnson — meaning that the reader’s appetite for weirdness is very quickly surfeited. Burgess (unlike, say, Kafka) is sensitive to this near-infallible law; but there’s a case for saying that “A Clockwork Orange” ought to be even shorter than its 141 pages. It was in fact published with two different endings. The American edition omits the final chapter (this is the version used by Kubrick) and closes with Alex recovering from what proves to be a cathartic suicide attempt. He is listening to Beethoven’s Ninth:

“When it came to the Scherzo I could viddy myself very clear running and running on like very light and mysterious nogas, carving the whole litso of the creeching world with my cut-throat britva. And there was the slow movement and the lovely last singing movement still to come. I was cured all right.”

This is the “dark” ending. In the official version, though, Alex is afforded full redemption. He simply — and bathetically — “outgrows” the atavisms of youth, and starts itching to get married and settle down; and he carries around with him a photo of “a baby gurgling goo goo goo.” We are asked to accept that Alex has turned all soft and broody — at the age of 18.

It feels like a startling loss of nerve on Burgess’ part, or a recrudescence (we recall that he was an Augustinian Catholic) of self-punitive guilt. Horrified by its own transgressive energy, the novel submits to a Reclamation Treatment sternly supplied by its author. Burgess knew something was wrong: “a work too didactic to be artistic,” he half-conceded, “pure art dragged into the arena of morality.” And he shouldn’t have worried: Alex may be a teenager, but readers are grown-ups, and are perfectly at peace with the unregenerate. Besides, “A Clockwork Orange” is in essence a black comedy. Confronted by evil, comedy feels no need to punish or correct. It answers with corrosive laughter.

In his 1973 book on Joyce, “Joysprick,” Burgess made a provocative distinction between what he calls the “A” novelist and the “B” novelist: the A novelist is interested in plot, character and psychological insight, whereas the B novelist is interested, above all, in the play of words. The most famous B novel is “Finnegans Wake,” which Nabokov aptly described as “a cold pudding of a book, a persistent snore in the next room.” The B novel, as a genre, is now utterly defunct; and “A Clockwork Orange” may be its only long-term survivor. It is a book that can still be read with steady pleasure, continuous amusement and — at times — incredulous admiration. Anthony Burgess, then, is not “a minor B novelist,” as he described himself; he is the only B novelist. I think he would have settled for that.

~ Martin Amis is the author, most recently, of “Lionel Asbo: State of England.” This essay is adapted from his introduction to a new 50th-anniversary edition of “A Clockwork Orange” published in Britain by William Heinemann.

.

Ryan actually asked for federal spending to save the plant, while

Romney has criticized the auto industry bailout that President Obama

ultimately enacted to prevent other plants from closing.

.

Ryan actually asked for federal spending to save the plant, while

Romney has criticized the auto industry bailout that President Obama

ultimately enacted to prevent other plants from closing.