In this week's episode of

The Philosopher's Zone (on Australia's Radio National), Joe Gelonesi speaks with two philosophers -

Hubert Dreyfus and

David Deutsch - on the prospect of an artificial intelligence (AI).

Dreyfus has been critical of the AI enterprize since back in the 1950s and 60s, producing a list of the four basic assumptions of AI believers (via

Wikipedia):

Dreyfus identified four philosophical assumptions that supported the faith of early AI researchers that human intelligence depended on the manipulation of symbols.[9] "In each case," Dreyfus writes, "the assumption is taken by workers in [AI] as an axiom, guaranteeing results, whereas it is, in fact, one hypothesis among others, to be tested by the success of such work."[10]

The biological assumption

The brain processes information in discrete operations by way of some biological equivalent of on/off switches.

In the early days of research into neurology, scientists realized that neurons fire in all-or-nothing pulses. Several researchers, such as Walter Pitts and Warren McCulloch, argued that neurons functioned similar to the way Boolean logic gates operate, and so could be imitated by electronic circuitry at the level of the neuron.[11] When digital computers became widely used in the early 50s, this argument was extended to suggest that the brain was a vast physical symbol system, manipulating the binary symbols of zero and one. Dreyfus was able to refute the biological assumption by citing research in neurology that suggested that the action and timing of neuron firing had analog components.[12] To be fair, however, Daniel Crevier observes that "few still held that belief in the early 1970s, and nobody argued against Dreyfus" about the biological assumption.[13]

The psychological assumption

The mind can be viewed as a device operating on bits of information according to formal rules.

He refuted this assumption by showing that much of what we "know" about the world consists of complex attitudes or tendencies that make us lean towards one interpretation over another. He argued that, even when we use explicit symbols, we are using them against an unconscious background of commonsense knowledge and that without this background our symbols cease to mean anything. This background, in Dreyfus' view, was not implemented in individual brains as explicit individual symbols with explicit individual meanings.

The epistemological assumption

All knowledge can be formalized.

This concerns the philosophical issue of epistemology, or the study of knowledge. Even if we agree that the psychological assumption is false, AI researchers could still argue (as AI founder John McCarthy has) that it was possible for a symbol processing machine to represent all knowledge, regardless of whether human beings represented knowledge the same way. Dreyfus argued that there was no justification for this assumption, since so much of human knowledge was not symbolic.

The ontological assumption

The world consists of independent facts that can be represented by independent symbols.

Dreyfus also identified a subtler assumption about the world. AI researchers (and futurists and science fiction writers) often assume that there is no limit to formal, scientific knowledge, because they assume that any phenomenon in the universe can be described by symbols or scientific theories. This assumes that everything that exists can be understood as objects, properties of objects, classes of objects, relations of objects, and so on: precisely those things that can be described by logic, language and mathematics. The question of what exists is called ontology, and so Dreyfus calls this "the ontological assumption:" If this is false, then it raises doubts about what we can ultimately know and on what intelligent machines will ultimately be able to help us to do.

For what it's worth, and coming as no surprise to readers of this blog, I tend to agree with Dreyfus's assessment of the four, false assumptions.

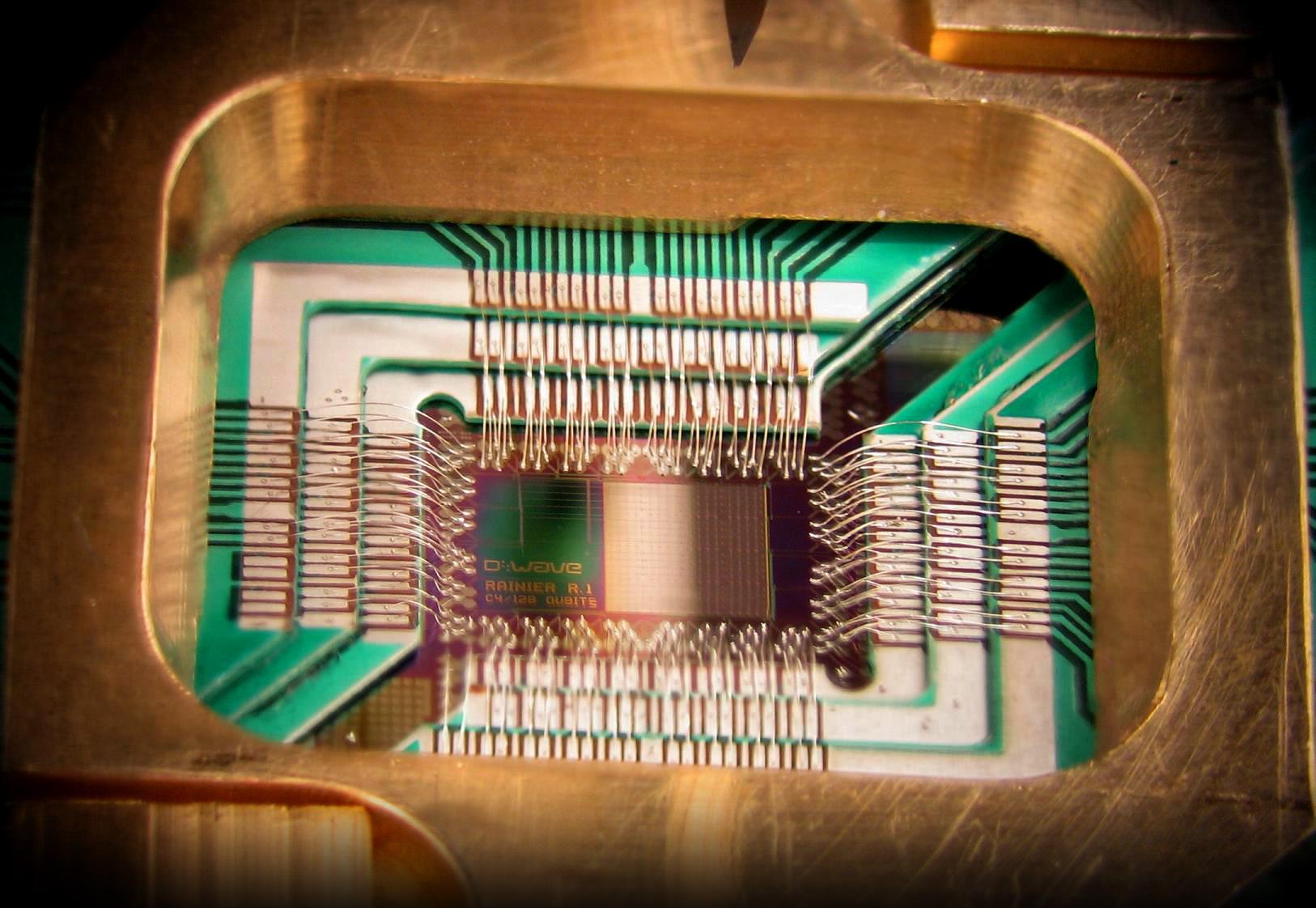

On the other side of the debate is David Deutsch, an expert in the field of

quantum computation and creator of a description for a

quantum Turing machine (he also has specified an algorithm designed to run on a quantum computer

[2]).

Deutsch is also the articulator of a TOE (theory of everything), one that sounds intriguing (although it needs a couple of tweeks). Via

Wikipedia:

In his 1997 book The Fabric of Reality: Towards a Theory of Everything (1998), Deutsch details his "Theory of Everything." It aims not at the reduction of everything to particle physics, but rather mutual support among multiversal, computational, epistemological, and evolutionary principles. His theory of everything is (weakly) emergentist rather than reductive.

There are "four strands" to his theory:

- Hugh Everett's many-worlds interpretation of quantum physics, "the first and most important of the four strands."

- Karl Popper's epistemology, especially its anti-inductivism and requiring a realist (non-instrumental) interpretation of scientific theories, as well as its emphasis on taking seriously those bold conjectures that resist falsification.

- Alan Turing's theory of computation, especially as developed in Deutsch's Turing principle, in which the Universal Turing machine is replaced by Deutsch's universal quantum computer. ("The theory of computation is now the quantum theory of computation.")

- Richard Dawkins's refinement of Darwinian evolutionary theory and the modern evolutionary synthesis, especially the ideas of replicator and meme as they integrate with Popperian problem-solving (the epistemological strand).

With that background, on to the podcast.

Sunday 30 June 2013

IMAGE: WHAT WILL IT TAKE TO CREATE TRUE ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE? THE PHILOSOPHERS COULD HOLD THE KEY.(IMAGES ETC LTD/GETTY)

After decades of research, the thinking computer remains a distant dream. They can play chess, drive cars, and communicate with each other, but thinking like humans remains a step beyond. Now, the inventor of quantum computation, David Deutsch, has called for a wholesale change in thinking to break the impasse. Enter the philosophers.

Guests

Professor Hubert Dreyfus, University of California, Berkeley

David Deutsch, Centre for Quantum Computation, University of Oxford

Presenter: Joe Gelonesi

Producer: Diane Dean