In the November issue of

The Atlantic, James Somers offers an in-depth p

rofile of Douglas Hofstadter, a man who is simultaneously brilliant and annoying. I do not share his belief and the possibility of a true artificial intelligence (AI), so this part of his body of work is vaguely annoying.

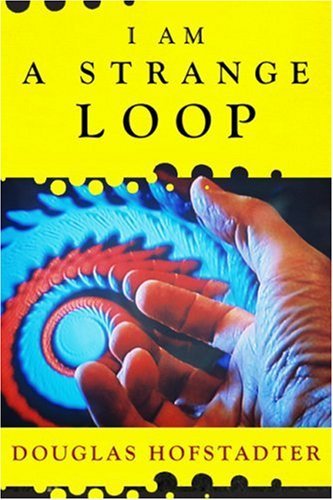

However, as he has worked on the AI problem, he was watched how his own mind works in the process, a kind of process mindfulness. The result, for me, was one of his best books, but one not even mentioned in this article -

I Am a Strange Loop. As I read this book, it seemed like the cognitive science version of the neurobiology Antonio Damasio has been presenting in his work, most notably in

The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness (2000),

Looking for Spinoza: Joy, Sorrow, and the Feeling Brain (2003), and

Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain (2012).

This article is part of an Atlantic special report on

Imagination, optimism, and the nature of progress.

Douglas Hofstadter, the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Gödel, Escher, Bach, thinks we've lost sight of what artificial intelligence really means. His stubborn quest to replicate the human mind.

James Somers | Oct 23 2013

November 2013 Issue

“It depends on what you mean by artificial intelligence.” Douglas Hofstadter is in a grocery store in Bloomington, Indiana, picking out salad ingredients. “If somebody meant by artificial intelligence the attempt to understand the mind, or to create something human-like, they might say—maybe they wouldn’t go this far—but they might say this is some of the only good work that’s ever been done.”

Hofstadter says this with an easy deliberateness, and he says it that way because for him, it is an uncontroversial conviction that the most-exciting projects in modern artificial intelligence, the stuff the public maybe sees as stepping stones on the way to science fiction—like Watson, IBM’s Jeopardy-playing supercomputer, or Siri, Apple’s iPhone assistant—in fact have very little to do with intelligence. For the past 30 years, most of them spent in an old house just northwest of the Indiana University campus, he and his graduate students have been picking up the slack: trying to figure out how our thinking works, by writing computer programs that think.Their operating premise is simple: the mind is a very unusual piece of software, and the best way to understand how a piece of software works is to write it yourself. Computers are flexible enough to model the strange evolved convolutions of our thought, and yet responsive only to precise instructions. So if the endeavor succeeds, it will be a double victory: we will finally come to know the exact mechanics of our selves—and we’ll have made intelligent machines.

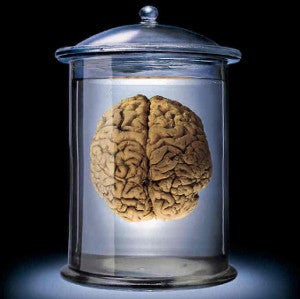

The idea that changed Hofstadter’s existence, as he has explained over the years, came to him on the road, on a break from graduate school in particle physics. Discouraged by the way his doctoral thesis was going at the University of Oregon, feeling “profoundly lost,” he decided in the summer of 1972 to pack his things into a car he called Quicksilver and drive eastward across the continent. Each night he pitched his tent somewhere new (“sometimes in a forest, sometimes by a lake”) and read by flashlight. He was free to think about whatever he wanted; he chose to think about thinking itself. Ever since he was about 14, when he found out that his youngest sister, Molly, couldn’t understand language, because she “had something deeply wrong with her brain” (her neurological condition probably dated from birth, and was never diagnosed), he had been quietly obsessed by the relation of mind to matter. The father of psychology, William James, described this in 1890 as “the most mysterious thing in the world”: How could consciousness be physical? How could a few pounds of gray gelatin give rise to our very thoughts and selves?

Roaming in his 1956 Mercury, Hofstadter thought he had found the answer—that it lived, of all places, in the kernel of a mathematical proof. In 1931, the Austrian-born logician Kurt Gödel had famously shown how a mathematical system could make statements not just about numbers but about the system itself. Consciousness, Hofstadter wanted to say, emerged via just the same kind of “level-crossing feedback loop.” He sat down one afternoon to sketch his thinking in a letter to a friend. But after 30 handwritten pages, he decided not to send it; instead he’d let the ideas germinate a while. Seven years later, they had not so much germinated as metastasized into a 2.9‑pound, 777-page book called Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, which would earn for Hofstadter—only 35 years old, and a first-time author—the 1980 Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction.

GEB, as the book became known, was a sensation. Its success was catalyzed by Martin Gardner, a popular columnist for Scientific American, who very unusually devoted his space in the July 1979 issue to discussing one book—and wrote a glowing review. “Every few decades,” Gardner began, “an unknown author brings out a book of such depth, clarity, range, wit, beauty and originality that it is recognized at once as a major literary event.” The first American to earn a doctoral degree in computer science (then labeled “communication sciences”), John Holland, recalled that “the general response amongst people I know was that it was a wonderment.”

Hofstadter seemed poised to become an indelible part of the culture. GEB was not just an influential book, it was a book fully of the future. People called it the bible of artificial intelligence, that nascent field at the intersection of computing, cognitive science, neuroscience, and psychology. Hofstadter’s account of computer programs that weren’t just capable but creative, his road map for uncovering the “secret software structures in our minds,” launched an entire generation of eager young students into AI.

But then AI changed, and Hofstadter didn’t change with it, and for that he all but disappeared.

GEB arrived on the scene at an inflection point in AI’s history. In the early 1980s, the field was retrenching: funding for long-term “basic science” was drying up, and the focus was shifting to practical systems. Ambitious AI research had acquired a bad reputation. Wide-eyed overpromises were the norm, going back to the birth of the field in 1956 at the Dartmouth Summer Research Project, where the organizers—including the man who coined the term artificial intelligence, John McCarthy—declared that “if a carefully selected group of scientists work on it together for a summer,” they would make significant progress toward creating machines with one or more of the following abilities: the ability to use language; to form concepts; to solve problems now solvable only by humans; to improve themselves. McCarthy later recalled that they failed because “AI is harder than we thought.”

With wartime pressures mounting, a chief underwriter of AI research—the Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA)—tightened its leash. In 1969, Congress passed the Mansfield Amendment, requiring that Defense support only projects with “a direct and apparent relationship to a specific military function or operation.” In 1972, ARPA became DARPA, the D for “Defense,” to reflect its emphasis on projects with a military benefit. By the middle of the decade, the agency was asking itself: What concrete improvements in national defense did we just buy, exactly, with 10 years and $50 million worth of exploratory research?

By the early 1980s, the pressure was great enough that AI, which had begun as an endeavor to answer yes to Alan Turing’s famous question, “Can machines think?,” started to mature—or mutate, depending on your point of view—into a subfield of software engineering, driven by applications. Work was increasingly done over short time horizons, often with specific buyers in mind. For the military, favored projects included “command and control” systems, like a computerized in-flight assistant for combat pilots, and programs that would automatically spot roads, bridges, tanks, and silos in aerial photographs. In the private sector, the vogue was “expert systems,” niche products like a pile-selection system, which helped designers choose materials for building foundations, and the Automated Cable Expertise program, which ingested and summarized telephone-cable maintenance reports.

In GEB, Hofstadter was calling for an approach to AI concerned less with solving human problems intelligently than with understanding human intelligence—at precisely the moment that such an approach, having borne so little fruit, was being abandoned. His star faded quickly. He would increasingly find himself out of a mainstream that had embraced a new imperative: to make machines perform in any way possible, with little regard for psychological plausibility.

Take Deep Blue, the IBM supercomputer that bested the chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov. Deep Blue won by brute force. For each legal move it could make at a given point in the game, it would consider its opponent’s responses, its own responses to those responses, and so on for six or more steps down the line. With a fast evaluation function, it would calculate a score for each possible position, and then make the move that led to the best score. What allowed Deep Blue to beat the world’s best humans was raw computational power. It could evaluate up to 330 million positions a second, while Kasparov could evaluate only a few dozen before having to make a decision.

Hofstadter wanted to ask: Why conquer a task if there’s no insight to be had from the victory? “Okay,” he says, “Deep Blue plays very good chess—so what? Does that tell you something about how we play chess? No. Does it tell you about how Kasparov envisions, understands a chessboard?” A brand of AI that didn’t try to answer such questions—however impressive it might have been—was, in Hofstadter’s mind, a diversion. He distanced himself from the field almost as soon as he became a part of it. “To me, as a fledgling AI person,” he says, “it was self-evident that I did not want to get involved in that trickery. It was obvious: I don’t want to be involved in passing off some fancy program’s behavior for intelligence when I know that it has nothing to do with intelligence. And I don’t know why more people aren’t that way.”

One answer is that the AI enterprise went from being worth a few million dollars in the early 1980s to billions by the end of the decade. (After Deep Blue won in 1997, the value of IBM’s stock increased by $18 billion.) The more staid an engineering discipline AI became, the more it accomplished. Today, on the strength of techniques bearing little relation to the stuff of thought, it seems to be in a kind of golden age. AI pervades heavy industry, transportation, and finance. It powers many of Google’s core functions, Netflix’s movie recommendations, Watson, Siri, autonomous drones, the self-driving car.

“The quest for ‘artificial flight’ succeeded when the Wright brothers and others stopped imitating birds and started … learning about aerodynamics,” Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig write in their leading textbook, Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. AI started working when it ditched humans as a model, because it ditched them. That’s the thrust of the analogy: Airplanes don’t flap their wings; why should computers think?

It’s a compelling point. But it loses some bite when you consider what we want: a Google that knows, in the way a human would know, what you really mean when you search for something. Russell, a computer-science professor at Berkeley, said to me, “What’s the combined market cap of all of the search companies on the Web? It’s probably four hundred, five hundred billion dollars. Engines that could actually extract all that information and understand it would be worth 10 times as much.”

This, then, is the trillion-dollar question: Will the approach undergirding AI today—an approach that borrows little from the mind, that’s grounded instead in big data and big engineering—get us to where we want to go? How do you make a search engine that understands if you don’t know how you understand? Perhaps, as Russell and Norvig politely acknowledge in the last chapter of their textbook, in taking its practical turn, AI has become too much like the man who tries to get to the moon by climbing a tree: “One can report steady progress, all the way to the top of the tree.”

Consider that computers today still have trouble recognizing a handwritten A. In fact, the task is so difficult that it forms the basis for CAPTCHAs (“Completely Automated Public Turing tests to tell Computers and Humans Apart”), those widgets that require you to read distorted text and type the characters into a box before, say, letting you sign up for a Web site.

In Hofstadter’s mind, there is nothing to be surprised about. To know what all A’s have in common would be, he argued in a 1982 essay, to “understand the fluid nature of mental categories.” And that, he says, is the core of human intelligence.

“Cognition is recognition,” he likes to say. He describes “seeing as” as the essential cognitive act: you see some lines as “an A,” you see a hunk of wood as “a table,” you see a meeting as “an emperor-has-no-clothes situation” and a friend’s pouting as “sour grapes” and a young man’s style as “hipsterish” and on and on ceaselessly throughout your day. That’s what it means to understand. But how does understanding work? For three decades, Hofstadter and his students have been trying to find out, trying to build “computer models of the fundamental mechanisms of thought.”

“At every moment,” Hofstadter writes in Surfaces and Essences, his latest book (written with Emmanuel Sander), “we are simultaneously faced with an indefinite number of overlapping and intermingling situations.” It is our job, as organisms that want to live, to make sense of that chaos. We do it by having the right concepts come to mind. This happens automatically, all the time. Analogy is Hofstadter’s go-to word. The thesis of his new book, which features a mélange of A’s on its cover, is that analogy is “the fuel and fire of thinking,” the bread and butter of our daily mental lives.

“Look at your conversations,” he says. “You’ll see over and over again, to your surprise, that this is the process of analogy-making.” Someone says something, which reminds you of something else; you say something, which reminds the other person of something else—that’s a conversation. It couldn’t be more straightforward. But at each step, Hofstadter argues, there’s an analogy, a mental leap so stunningly complex that it’s a computational miracle: somehow your brain is able to strip any remark of the irrelevant surface details and extract its gist, its “skeletal essence,” and retrieve, from your own repertoire of ideas and experiences, the story or remark that best relates.

“Beware,” he writes, “of innocent phrases like ‘Oh, yeah, that’s exactly what happened to me!’ … behind whose nonchalance is hidden the entire mystery of the human mind.”

In the years after the release of GEB, Hofstadter and AI went their separate ways. Today, if you were to pull AI: A Modern Approach off the shelf, you wouldn’t find Hofstadter’s name—not in more than 1,000 pages. Colleagues talk about him in the past tense. New fans of GEB, seeing when it was published, are surprised to find out its author is still alive.

Of course in Hofstadter’s telling, the story goes like this: when everybody else in AI started building products, he and his team, as his friend, the philosopher Daniel Dennett, wrote, “patiently, systematically, brilliantly,” way out of the light of day, chipped away at the real problem. “Very few people are interested in how human intelligence works,” Hofstadter says. “That’s what we’re interested in—what is thinking?—and we don’t lose track of that question.”

“I mean, who knows?” he says. “Who knows what’ll happen. Maybe someday people will say, ‘Hofstadter already did this stuff and said this stuff and we’re just now discovering it.’ ”

Which sounds exactly like the self-soothing of the guy who lost. But Hofstadter has the kind of mind that tempts you to ask: What if the best ideas in artificial intelligence—“genuine artificial intelligence,” as Hofstadter now calls it, with apologies for the oxymoron—are yellowing in a drawer in Bloomington?

Douglas R. Hofstadter was born into a life of the mind the way other kids are born into a life of crime. He grew up in 1950s Stanford, in a house on campus, just south of a neighborhood actually called Professorville. His father, Robert, was a nuclear physicist who would go on to share the 1961 Nobel Prize in Physics; his mother, Nancy, who had a passion for politics, became an advocate for developmentally disabled children and served on the ethics committee of the Agnews Developmental Center, where Molly lived for more than 20 years. In her free time Nancy was, the joke went, a “professional faculty wife”: she transformed the Hofstadters’ living room into a place where a tight-knit community of friends could gather for stimulating conversation and jazz, for “the interpenetration of the sciences and the arts,” Hofstadter told me—an intellectual feast.

Dougie ate it up. He was enamored of his parents’ friends, their strange talk about “the tiniest or gigantic-est things.” (At age 8, he once said, his dream was to become “a zero-mass, spin one-half neutrino.”) He’d hang around the physics department for 4 o’clock tea, “as if I were a little 12-year-old graduate student.” He was curious, insatiable, unboreable—“just a kid fascinated by ideas”—and intense. His intellectual style was, and is, to go on what he calls “binges”: he might practice piano for seven hours a day; he might decide to memorize 1,200 lines of Eugene Onegin. He once spent weeks with a tape recorder teaching himself to speak backwards, so that when he played his garbles in reverse they came out as regular English. For months at a time he’ll immerse himself in idiomatic French or write computer programs to generate nonsensical stories or study more than a dozen proofs of the Pythagorean theorem until he can “see the reason it’s true.” He spends “virtually every day exploring these things,” he says, “unable to not explore. Just totally possessed, totally obsessed, by this kind of stuff.”

Hofstadter is 68 years old. But there’s something Peter Pan–ish about a life lived so much on paper, in software, in a man’s own head. Can someone like that age in the usual way? Hofstadter has untidy gray hair that juts out over his ears, a fragile, droopy stature, and, between his nose and upper lip, a long groove, almost like the Grinch’s. But he has the self-seriousness, the urgent earnestness, of a still very young man. The stakes are high with him; he isn’t easygoing. He’s the kind of vegetarian who implores the whole dinner party to eat vegetarian too; the kind of sensitive speaker who corrects you for using “sexist language” around him. “He has these rules,” explains his friend Peter Jones, who’s known Hofstadter for 59 years. “Like how he hates you guys. That’s an imperative. If you’re talking to him, you better not say you guys.”

For more than 30 years, Hofstadter has worked as a professor at Indiana University at Bloomington. He lives in a house a few blocks from campus with Baofen Lin, whom he married last September; his two children by his previous marriage, Danny and Monica, are now grown. Although he has strong ties with the cognitive-science program and affiliations with several departments—including computer science, psychological and brain sciences, comparative literature, and philosophy—he has no official obligations. “I think I have about the cushiest job you could imagine,” he told me. “I do exactly what I want.”

He spends most of his time in his study, two rooms on the top floor of his house, carpeted, a bit stuffy, and messier than he would like. His study is the center of his world. He reads there, listens to music there, studies there, draws there, writes his books there, writes his e‑mails there. (Hofstadter spends four hours a day writing e‑mail. “To me,” he has said, “an e‑mail is identical to a letter, every bit as formal, as refined, as carefully written … I rewrite, rewrite, rewrite, rewrite all of my e‑mails, always.”) He lives his mental life there, and it shows. Wall-to-wall there are books and drawings and notebooks and files, thoughts fossilized and splayed all over the room. It’s like a museum for his binges, a scene out of a brainy episode of Hoarders.

“Anything that I think about becomes part of my professional life,” he says. Daniel Dennett, who co-edited The Mind’s I with him, has explained that “what Douglas Hofstadter is, quite simply, is a phenomenologist, a practicing phenomenologist, and he does it better than anybody else. Ever.” He studies the phenomena—the feelings, the inside actions—of his own mind. “And the reason he’s good at it,” Dennett told me, “the reason he’s better than anybody else, is that he is very actively trying to have a theory of what’s going on backstage, of how thinking actually happens in the brain.”

In his back pocket, Hofstadter carries a four-color Bic ballpoint pen and a small notebook. It’s always been that way. In what used to be a bathroom adjoined to his study but is now just extra storage space, he has bookshelves full of these notebooks. He pulls one down—it’s from the late 1950s. It’s full of speech errors. Ever since he was a teenager, he has captured some 10,000 examples of swapped syllables (“hypodeemic nerdle”), malapropisms (“runs the gambit”), “malaphors” (“easy-go-lucky”), and so on, about half of them committed by Hofstadter himself. He makes photocopies of his notebook pages, cuts them up with scissors, and stores the errors in filing cabinets and labeled boxes around his study.

For Hofstadter, they’re clues. “Nobody is a very reliable guide concerning activities in their mind that are, by definition, subconscious,” he once wrote. “This is what makes vast collections of errors so important. In an isolated error, the mechanisms involved yield only slight traces of themselves; however, in a large collection, vast numbers of such slight traces exist, collectively adding up to strong evidence for (and against) particular mechanisms.” Correct speech isn’t very interesting; it’s like a well-executed magic trick—effective because it obscures how it works. What Hofstadter is looking for is “a tip of the rabbit’s ear … a hint of a trap door.”

In this he is the modern-day William James, whose blend of articulate introspection (he introduced the idea of the stream of consciousness) and crisp explanations made his 1890 text, Principles of Psychology, a classic. “The mass of our thinking vanishes for ever, beyond hope of recovery,” James wrote, “and psychology only gathers up a few of the crumbs that fall from the feast.” Like Hofstadter, James made his life playing under the table, gleefully inspecting those crumbs. The difference is that where James had only his eyes, Hofstadter has something like a microscope.

You can credit the development of manned aircraft not to the Wright brothers’ glider flights at Kitty Hawk but to the six-foot wind tunnel they built for themselves in their bicycle shop using scrap metal and recycled wheel spokes. While their competitors were testing wing ideas at full scale, the Wrights were doing focused aerodynamic experiments at a fraction of the cost. Their biographer Fred Howard says that these were “the most crucial and fruitful aeronautical experiments ever conducted in so short a time with so few materials and at so little expense.”

In an old house on North Fess Avenue in Bloomington, Hofstadter directs the Fluid Analogies Research Group, affectionately known as FARG. The yearly operating budget is $100,000. Inside, it’s homey—if you wandered through, you could easily miss the filing cabinets tucked beside the pantry, the photocopier humming in the living room, the librarian’s labels (Neuroscience, MATHEMATICS, Perception) on the bookshelves. But for 25 years, this place has been host to high enterprise, as the small group of scientists tries, Hofstadter has written, “first, to uncover the secrets of creativity, and second, to uncover the secrets of consciousness.”

As the wind tunnel was to the Wright brothers, so the computer is to FARG. The quick unconscious chaos of a mind can be slowed down on the computer, or rewound, paused, even edited. In Hofstadter’s view, this is the great opportunity of artificial intelligence. Parts of a program can be selectively isolated to see how it functions without them; parameters can be changed to see how performance improves or degrades. When the computer surprises you—whether by being especially creative or especially dim-witted—you can see exactly why. “I have always felt that the only hope of humans ever coming to fully understand the complexity of their minds,” Hofstadter has written, “is by modeling mental processes on computers and learning from the models’ inevitable failures.”

Turning a mental process caught and catalogued in Hofstadter’s house into a running computer program, just a mile up the road, takes a dedicated graduate student about five to nine years. The programs all share the same basic architecture—a set of components and an overall style that traces back to Jumbo, a program that Hofstadter wrote in 1982 that worked on the word jumbles you find in newspapers.

The first thought you ought to have when you hear about a program that’s tackling newspaper jumbles is: Wouldn’t those be trivial for a computer to solve? And indeed they are—I just wrote a program that can handle any word, and it took me four minutes. My program works like this: it takes the jumbled word and tries every rearrangement of its letters until it finds a word in the dictionary.

Hofstadter spent two years building Jumbo: he was less interested in solving jumbles than in finding out what was happening when he solved them. He had been watching his mind. “I could feel the letters shifting around in my head, by themselves,” he told me, “just kind of jumping around forming little groups, coming apart, forming new groups—flickering clusters. It wasn’t me manipulating anything. It was just them doing things. They would be trying things themselves.”

The architecture Hofstadter developed to model this automatic letter-play was based on the actions inside a biological cell. Letters are combined and broken apart by different types of “enzymes,” as he says, that jiggle around, glomming on to structures where they find them, kicking reactions into gear. Some enzymes are rearrangers (pang-loss becomes pan-gloss or lang-poss), others are builders (g and h become the cluster gh; jum and ble become jumble), and still others are breakers (ight is broken into it and gh). Each reaction in turn produces others, the population of enzymes at any given moment balancing itself to reflect the state of the jumble.

It’s an unusual kind of computation, distinct for its fluidity. Hofstadter of course offers an analogy: a swarm of ants rambling around the forest floor, as scouts make small random forays in all directions and report their finds to the group, their feedback driving an efficient search for food. Such a swarm is robust—step on a handful of ants and the others quickly recover—and, because of that robustness, adept.

When you read Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies: Computer Models of the Fundamental Mechanisms of Thought, which describes in detail this architecture and the logic and mechanics of the programs that use it, you wonder whether maybe Hofstadter got famous for the wrong book. As a writer for The New York Times once put it in a 1995 review, “The reader of ‘Fluid Concepts & Creative Analogies’ cannot help suspecting that the group at Indiana University is on to something momentous.”

But very few people, even admirers of GEB, know about the book or the programs it describes. And maybe that’s because FARG’s programs are almost ostentatiously impractical. Because they operate in tiny, seemingly childish “microdomains.” Because there is no task they perform better than a human.

The modern era of mainstream AI—an era of steady progress and commercial success that began, roughly, in the early 1990s and continues to this day—is the long unlikely springtime after a period, known as the AI Winter, that nearly killed off the field.

It came down to a basic dilemma. On the one hand, the software we know how to write is very orderly; most computer programs are organized like a well-run army, with layers of commanders, each layer passing instructions down to the next, and routines that call subroutines that call subroutines. On the other hand, the software we want to write would be adaptable—and for that, a hierarchy of rules seems like just the wrong idea. Hofstadter once summarized the situation by writing, “The entire effort of artificial intelligence is essentially a fight against computers’ rigidity.” In the late ’80s, mainstream AI was losing research dollars, clout, conference attendance, journal submissions, and press—because it was getting beat in that fight.

The “expert systems” that had once been the field’s meal ticket were foundering because of their brittleness. Their approach was fundamentally broken. Take machine translation from one language to another, long a holy grail of AI. The standard attack involved corralling linguists and translators into a room and trying to convert their expertise into rules for a program to follow. The standard attack failed for reasons you might expect: no set of rules can ever wrangle a human language; language is too big and too protean; for every rule obeyed, there’s a rule broken.

If machine translation was to survive as a commercial enterprise—if AI was to survive—it would have to find another way. Or better yet, a shortcut.

And it did. You could say that it started in 1988, with a project out of IBM called Candide. The idea behind Candide, a machine-translation system, was to start by admitting that the rules-based approach requires too deep an understanding of how language is produced; how semantics, syntax, and morphology work; and how words commingle in sentences and combine into paragraphs—to say nothing of understanding the ideas for which those words are merely conduits. So IBM threw that approach out the window. What the developers did instead was brilliant, but so straightforward, you can hardly believe it.

The technique is called “machine learning.” The goal is to make a device that takes an English sentence as input and spits out a French sentence. One such device, of course, is the human brain—but the whole point is to avoid grappling with the brain’s complexity. So what you do instead is start with a machine so simple, it almost doesn’t work: a machine, say, that randomly spits out French words for the English words it’s given.

Imagine a box with thousands of knobs on it. Some of these knobs control general settings: given one English word, how many French words, on average, should come out? And some control specific settings: given jump, what is the probability that shot comes next? The question is, just by tuning these knobs, can you get your machine to convert sensible English into sensible French?

It turns out that you can. What you do is feed the machine English sentences whose French translations you already know. (Candide, for example, used 2.2 million pairs of sentences, mostly from the bilingual proceedings of Canadian parliamentary debates.) You proceed one pair at a time. After you’ve entered a pair, take the English half and feed it into your machine to see what comes out in French. If that sentence is different from what you were expecting—different from the known correct translation—your machine isn’t quite right. So jiggle the knobs and try again. After enough feeding and trying and jiggling, feeding and trying and jiggling again, you’ll get a feel for the knobs, and you’ll be able to produce the correct French equivalent of your English sentence.

By repeating this process with millions of pairs of sentences, you will gradually calibrate your machine, to the point where you’ll be able to enter a sentence whose translation you don’t know and get a reasonable result. And the beauty is that you never needed to program the machine explicitly; you never needed to know why the knobs should be twisted this way or that.

Candide didn’t invent machine learning—in fact the concept had been tested plenty before, in a primitive form of machine translation in the 1960s. But up to that point, no test had been very successful. The breakthrough wasn’t that Candide cracked the problem. It was that so simple a program performed adequately. Machine translation was, as Adam Berger, a member of the Candide team, writes in a summary of the project, “widely considered among the most difficult tasks in natural language processing, and in artificial intelligence in general, because accurate translation seems to be impossible without a comprehension of the text to be translated.” That a program as straightforward as Candide could perform at par suggested that effective machine translation didn’t require comprehension—all it required was lots of bilingual text. And for that, it became a proof of concept for the approach that conquered AI.

What Candide’s approach does, and with spectacular efficiency, is convert the problem of unknotting a complex process into the problem of finding lots and lots of examples of that process in action. This problem, unlike mimicking the actual processes of the brain, only got easier with time—particularly as the late ’80s rolled into the early ’90s and a nerdy haven for physicists exploded into the World Wide Web.

It is no coincidence that AI saw a resurgence in the ’90s, and no coincidence either that Google, the world’s biggest Web company, is “the world’s biggest AI system,” in the words of Peter Norvig, a director of research there, who wrote AI: A Modern Approach with Stuart Russell. Modern AI, Norvig has said, is about “data, data, data,” and Google has more data than anyone else.

Josh Estelle, a software engineer on Google Translate, which is based on the same principles as Candide and is now the world’s leading machine-translation system, explains, “you can take one of those simple machine-learning algorithms that you learned about in the first few weeks of an AI class, an algorithm that academia has given up on, that’s not seen as useful—but when you go from 10,000 training examples to 10 billion training examples, it all starts to work. Data trumps everything.”

The technique is so effective that the Google Translate team can be made up of people who don’t speak most of the languages their application translates. “It’s a bang-for-your-buck argument,” Estelle says. “You probably want to hire more engineers instead” of native speakers. Engineering is what counts in a world where translation is an exercise in data-mining at a massive scale.

That’s what makes the machine-learning approach such a spectacular boon: it vacuums out the first-order problem, and replaces the task of understanding with nuts-and-bolts engineering. “You saw this springing up throughout” Google, Norvig says. “If we can make this part 10 percent faster, that would save so many millions of dollars per year, so let’s go ahead and do it. How are we going to do it? Well, we’ll look at the data, and we’ll use a machine-learning or statistical approach, and we’ll come up with something better.”

Google has projects that gesture toward deeper understanding: extensions of machine learning inspired by brain biology; a “knowledge graph” that tries to map words, like Obama, to people or places or things. But the need to serve 1 billion customers has a way of forcing the company to trade understanding for expediency. You don’t have to push Google Translate very far to see the compromises its developers have made for coverage, and speed, and ease of engineering. Although Google Translate captures, in its way, the products of human intelligence, it isn’t intelligent itself. It’s like an enormous Rosetta Stone, the calcified hieroglyphics of minds once at work.

“Did we sit down when we built Watson and try to model human cognition?” Dave Ferrucci, who led the Watson team at IBM, pauses for emphasis. “Absolutely not. We just tried to create a machine that could win at Jeopardy.”

For Ferrucci, the definition of intelligence is simple: it’s what a program can do. Deep Blue was intelligent because it could beat Garry Kasparov at chess. Watson was intelligent because it could beat Ken Jennings at Jeopardy. “It’s artificial intelligence, right? Which is almost to say not-human intelligence. Why would you expect the science of artificial intelligence to produce human intelligence?”

Ferrucci is not blind to the difference. He likes to tell crowds that whereas Watson played using a room’s worth of processors and 20 tons of air-conditioning equipment, its opponents relied on a machine that fits in a shoebox and can run for hours on a tuna sandwich. A machine, no less, that would allow them to get up when the match was over, have a conversation, enjoy a bagel, argue, dance, think—while Watson would be left humming, hot and dumb and un-alive, answering questions about presidents and potent potables.

“The features that [these systems] are ultimately looking at are just shadows—they’re not even shadows—of what it is that they represent,” Ferrucci says. “We constantly underestimate—we did in the ’50s about AI, and we’re still doing it—what is really going on in the human brain.”

The question that Hofstadter wants to ask Ferrucci, and everybody else in mainstream AI, is this: Then why don’t you come study it?

“I have mixed feelings about this,” Ferrucci told me when I put the question to him last year. “There’s a limited number of things you can do as an individual, and I think when you dedicate your life to something, you’ve got to ask yourself the question: To what end? And I think at some point I asked myself that question, and what it came out to was, I’m fascinated by how the human mind works, it would be fantastic to understand cognition, I love to read books on it, I love to get a grip on it”—he called Hofstadter’s work inspiring—“but where am I going to go with it? Really what I want to do is build computer systems that do something. And I don’t think the short path to that is theories of cognition.”

Peter Norvig, one of Google’s directors of research, echoes Ferrucci almost exactly. “I thought he was tackling a really hard problem,” he told me about Hofstadter’s work. “And I guess I wanted to do an easier problem.”

In their responses, one can see the legacy of AI’s failures. Work on fundamental problems reeks of the early days. “Concern for ‘respectability,’ ” Nils Nilsson writes in his academic history, The Quest for Artificial Intelligence, “has had, I think, a stultifying effect on some AI researchers.”

Stuart Russell, Norvig’s co-author of AI: A Modern Approach, goes further. “A lot of the stuff going on is not very ambitious,” he told me. “In machine learning, one of the big steps that happened in the mid-’80s was to say, ‘Look, here’s some real data—can I get my program to predict accurately on parts of the data that I haven’t yet provided to it?’ What you see now in machine learning is that people see that as the only task.”

It’s insidious, the way your own success can stifle you. As our machines get faster and ingest more data, we allow ourselves to be dumber. Instead of wrestling with our hardest problems in earnest, we can just plug in billions of examples of them. Which is a bit like using a graphing calculator to do your high-school calculus homework—it works great until you need to actually understand calculus.

It seems unlikely that feeding Google Translate 1 trillion documents, instead of 10 billion, will suddenly enable it to work at the level of a human translator. The same goes for search, or image recognition, or question-answering, or planning or reading or writing or design, or any other problem for which you would rather have a human’s intelligence than a machine’s.

This is a fact of which Norvig, just like everybody else in commercial AI, seems to be aware, if not dimly afraid. “We could draw this curve: as we gain more data, how much better does our system get?” he says. “And the answer is, it’s still improving—but we are getting to the point where we get less benefit than we did in the past.”

For James Marshall, a former graduate student of Hofstadter’s, it’s simple: “In the end, the hard road is the only one that’s going to lead you all the way.”

Hofstadter was 35 when he had his first long-term romantic relationship. He was born, he says, with “a narrow resonance curve,” borrowing a concept from physics to describe his extreme pickiness. “There have been certain women who have had an enormous effect on me; their face has had an incredible effect on me. I can’t give you a recipe for the face … but it’s very rare.” In 1980, after what he has described as “15 hellish, love-bleak years,” he met Carol Brush. (“She was at the dead center of the resonance curve.”) Not long after they met, they were happily married with two kids, and not long after that, while they were on sabbatical together in Italy in 1993, Carol died suddenly of a brain tumor. Danny and Monica were 5 and 2 years old. “I felt that he was pretty much lost a long time after Carol’s death,” says Pentti Kanerva, a longtime friend.

Hofstadter hasn’t been to an artificial-intelligence conference in 30 years. “There’s no communication between me and these people,” he says of his AI peers. “None. Zero. I don’t want to talk to colleagues that I find very, very intransigent and hard to convince of anything. You know, I call them colleagues, but they’re almost not colleagues—we can’t speak to each other.”

Hofstadter strikes me as difficult, in a quiet way. He is kind, but he doesn’t do the thing that easy conversationalists do, that well-liked teachers do, which is to take the best of what you’ve said—to work you into their thinking as an indispensable ally, as though their point ultimately depends on your contribution. I remember sitting in on a roundtable discussion that Hofstadter and his students were having and thinking of how little I saw his mind change. He seemed to be seeking consensus. The discussion had begun as an e-mail that he had sent out to a large list of correspondents; he seemed keenest on the replies that were keenest on him.

“So I don’t enjoy it,” he told me. “I don’t enjoy going to conferences and running into people who are stubborn and convinced of ideas I don’t think are correct, and who don’t have any understanding of my ideas. And I just like to talk to people who are a little more sympathetic.”

Ever since he was about 15, Hofstadter has read The Catcher in the Rye once every 10 years. In the fall of 2011, he taught an undergraduate seminar called “Why Is J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye a Great Novel?” He feels a deep kinship with Holden Caulfield. When I mentioned that a lot of the kids in my high-school class didn’t like Holden—they thought he was a whiner—Hofstadter explained that “they may not recognize his vulnerability.” You imagine him standing like Holden stood at the beginning of the novel, alone on the top of a hill, watching his classmates romp around at the football game below. “I have too many ideas already,” Hofstadter tells me. “I don’t need the stimulation of the outside world.”

Of course, the folly of being above the fray is that you’re also not a part of it. “There are very few ideas in science that are so black-and-white that people say ‘Oh, good God, why didn’t we think of that?’ ” says Bob French, a former student of Hofstadter’s who has known him for 30 years. “Everything from plate tectonics to evolution—all those ideas, someone had to fight for them, because people didn’t agree with those ideas. And if you don’t participate in the fight, in the rough-and-tumble of academia, your ideas are going to end up being sidelined by ideas which are perhaps not as good, but were more ardently defended in the arena.”

Hofstadter never much wanted to fight, and the double-edged sword of his career, if there is one, is that he never really had to. He won the Pulitzer Prize when he was 35, and instantly became valuable property to his university. He was awarded tenure. He didn’t have to submit articles to journals; he didn’t have to have them reviewed, or reply to reviews. He had a publisher, Basic Books, that would underwrite anything he sent them.

Stuart Russell puts it bluntly. “Academia is not an environment where you just sit in your bath and have ideas and expect everyone to run around getting excited. It’s possible that in 50 years’ time we’ll say, ‘We really should have listened more to Doug Hofstadter.’ But it’s incumbent on every scientist to at least think about what is needed to get people to understand the ideas.”

“Ars longa, vita brevis,” Hofstadter likes to say. “I just figure that life is short. I work, I don’t try to publicize. I don’t try to fight.”

There’s an analogy he made for me once. Einstein, he said, had come up with the light-quantum hypothesis in 1905. But nobody accepted it until 1923. “Not a soul,” Hofstadter says. “Einstein was completely alone in his belief in the existence of light as particles—for 18 years.

“That must have been very lonely.”

____

~ James Somers is a writer and computer programmer based in New York City.