This is a re-post of an older article from Nautilus, but it's worth the (re)read even if you saew it originally. Michael Tomasello is the primary expert here, and his book is listed below, along with a few others that are related and interesting reads.

Michael Tomasello, Why We Cooperate (2009)

Samuel Bowles, A Cooperative Species: Human Reciprocity and Its Evolution (2013)

Robert Axelrod, The Evolution of Cooperation: Revised Edition (2006)

Martin Nowak and Roger Highfield, SuperCooperators: Altruism, Evolution, and Why We Need Each Other to Succeed (2012)

Cooperation Is What Makes Us Human

Where we part ways with our ape cousins

TALES about the origins of our species always start off like this: A small band of hunter-gatherers roams the savannah, loving, warring, and struggling for survival under the African sun. They do not start like this: A fat guy falls off a New York City subway platform onto the tracks.

But what happens next is a quintessential story of who we are as human beings.

On Feb. 17, 2013, around 2:30 a.m., Garrett O’Hanlon, a U.S. Air Force Academy cadet third class, was out celebrating his 22nd birthday in New York City. He and his sister were in the subway waiting for a train when a sudden silence came over the platform, followed by a shriek. People pointed down to the tracks.

O’Hanlon turned and saw a man sprawled facedown on the tracks. “The next thing that happened, I was on the tracks, running toward him,” he says. “I honestly didn’t have a thought process.”

O’Hanlon grabbed the unconscious man by the shoulders, lifting his upper body off the tracks, but struggled to move him. He was deadweight. According to the station clock, the train would arrive in less than two minutes. From the platform, O’Hanlon’s sister was screaming at him to save himself.

Suddenly other arms were there: Personal trainer Dennis Codrington Jr. and his friend Matt Foley had also jumped down to help. “We grabbed him, one by the legs, one by the shoulders, one by the chest,” O’Hanlon says. They got the man to the edge of the platform, where a dozen or more people muscled him up and over. More hands seized the rescuers’ arms and shoulders, helping them up to safety as well.

In the aftermath of the rescue, O’Hanlon says he has been surprised that so many people have asked him why he did it. “I get stunned by the question,” he says. In his view, anybody else would’ve done the same thing. “I feel like it’s a normal reaction,” he says. “To me that’s just what people do.”

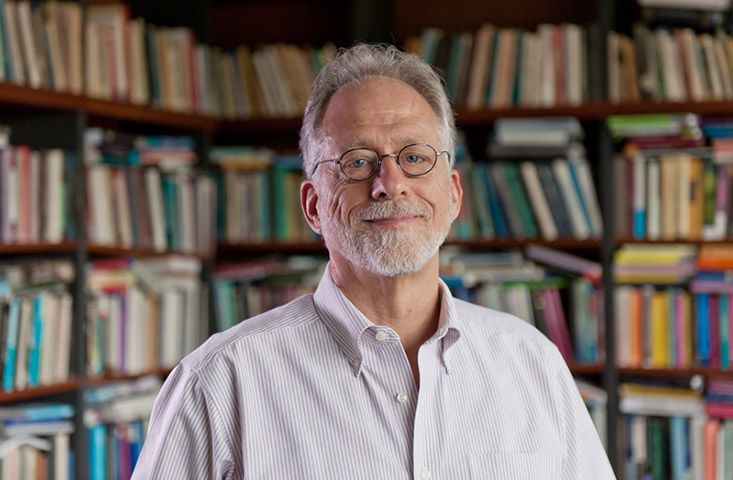

More precisely, it is something only people do, according to developmental psychologist Michael Tomasello, codirector of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

For decades Tomasello has explored what makes humans distinctive. His conclusion? We cooperate. Many species, from ants to orcas to our primate cousins, cooperate in the wild. But Tomasello has identified a special form of cooperation. In his view, humans alone are capable of shared intentionality—they intuitively grasp what another person is thinking and act toward a common goal, as the subway rescuers did. This supremely human cognitive ability, Tomasello says, launched our species on its extraordinary trajectory. It forged language, tools, and cultures—stepping-stones to our colonization of every corner of the planet.

In his most recent research, Tomasello has begun to look at the dark side of cooperation. “We are primates, and primates compete with one another,” Tomasello says. He explains cooperation evolved on top of a deep-seated competitive drive. “In many ways, this is the human dilemma,” he says.

In conversation, Tomasello, 63, is both passionate and circumspect. Even as he overturns entrenched views in primatology and anthropology he treads carefully, backing up his theories by citing his experiments in human and primate behavior. He is aware of criticism from primatologists such as Frans de Waal, director of Living Links, a division of the Yerkes National Primate Research Center at Emory University in Atlanta, who has said Tomasello underestimates the minds of chimps and overestimates the uniqueness of human cooperation.

Nonetheless, Tomasello’s fellow scientists credit him with brave experiments and ingenious insights. Carol Dweck, a professor of psychology at Stanford University, who has done seminal research in child psychology and intelligence, has called Tomasello “a pioneer.” Herbert Gintis, an economist and behavioral scientist at the Santa Fe Institute, an interdisciplinary science research institution, agrees. “His work is fabulous,” Gintis says. “It has made clear certain things about what it means to be human.”

Every Chimp for Himself

Tomasello calls his theory of cooperation the Vygotskian Intelligence Hypothesis. It is named for Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky, who argued in the 1920s that children’s minds do not automatically acquire skills, but develop full human intelligence only through cooperative teaching and social interactions. Tomasello applies this idea to the evolution of our species. He proposes that as many as 2 million years ago, as climate swings altered the availability and competition for food, our ancestors were forced to put their heads together to survive.

Tomasello began his research career at Emory University, working with apes at the Yerkes primate center. He acknowledges that chimpanzees, like humans, manage complex social lives, solve problems flexibly, and create and deploy tools. Nonetheless, “I take it as given that something is different,” he says. “Humans are doing something on a different level.”

As Tomasello began to study the cognition of chimpanzees and other great apes, he was influenced by pioneering child psychologist Jean Piaget, who recognized that children see the world differently. “He looked at children as if they were another species,” Tomasello says. “That’s the guiding image I started with.”

At the Yerkes primate center, Tomasello adopted an experimental method that he would develop throughout his career: systematically comparing the cognition of great apes and young children in head-to-head tests. Since the use of language is an obvious difference between humans and chimps, he began by looking at the precursors of speech. Great apes often communicate with gestures. Babies point before they talk. Presumably our hominid ancestors also gesticulated before they developed language. So Tomasello focused on pointing, devising dozens of studies to explore how and when chimps and children point.

He found a major difference between the two species. By the time a baby begins to point, at about nine months of age, she has already made several sophisticated cognitive leaps. When she points at a puppy and looks at you, she knows that her perspective may be different from yours (you haven’t noticed the pup), and she wants to share her information—doggie!—with you.

“We naturally inform people of things that are interesting or useful to them,” Tomasello says. “That’s unusual. Other animals don’t do that.” Pointing is an attempt to change your mental state. It is also a request for a joint experience: She wants you to look at the dog with her.

Chimps, by contrast, do not point things out to each other. Captive chimps will point for humans, but it’s to make a demand rather than to share information: I want that! Open the door! They do not understand informational human pointing, because they do not expect anyone to share information with them. In one of Tomasello’s experiments, food is hidden in one of two buckets. Even if the experimenter points to where it is, the chimp still chooses randomly. “It’s absolutely surprising,” Tomasello says. “They just don’t seem to get it."

In parallel experiments, children as young as 12 months have no trouble understanding an adult pointing a finger at a hidden reward. To understand pointing, Tomasello posits, you must form a “we intention,” a shared goal that both of you will pay attention to the same thing. Chimps don’t point because they don’t think in terms of “we.” They think in terms of “me.” “Cooperatively informing them of the location of food does not compute,” he says. The chimpanzee world is egocentric: Every chimp for himself.

The idea that chimps don’t work together appeared at first to contradict what some biologists had observed in the wild. Chimps take turns grooming one another, for example. They also form group hunting parties to encircle and kill red colobus monkeys, a favorite food. But these behaviors don’t require the kind of we intention that Tomasello was finding in even the youngest humans. Grooming is a tit-for-tat activity that merely requires two animals to alternate: Literally, I scratch your back, you scratch mine. There’s no need to jointly focus attention.

Chimps can also hunt together without deliberately coordinating, Tomasello reasons. If, during the chase, each chimp simply maximizes his own chances of catching the prey, each will position himself where he thinks the monkey will try to break out of the circle of predators. “This kind of hunting event is clearly a group activity of some complexity,” Tomasello writes in his book Why We Cooperate. “But wolves and lions do something very similar, and most researchers do not attribute to them any kind of joint goals or plans. The apes are engaged in a group activity in ‘I’ mode, not in ‘we’ mode.”

Michael TomaselloPhoto: Jacobs Foundation

Alone Together

Still, it was hard to tell exactly what was going on from watching wild animals. Lab experiments, where multiple animals can be tested in controlled situations and their responses measured and quantified, could clarify whether chimps even have a collaborative mode. Since collaboration requires that you understand what someone else wants and thinks, Tomasello explored whether chimps have what psychologists call “theory of mind,” or insight into what another individual might be thinking.

The consensus was that apes did not have this mental ability, but Tomasello and his team, including then undergraduate student Brian Hare, began devising ape-centric experiments to test whether that was truly the case. Rather than using psychology tests developed for human beings, as many ape researchers did, they invented new tests that were more relevant to the chimpanzee world.

Chimps are hierarchical with an alpha chimp getting priority in feeding. One experiment set a high-ranking chimp against a low-ranking one to compete for food. The researchers hid snacks in such a way that only the subordinate animal could see all the hiding places. When both animals were freed to go after the food, the subordinate dove for the snacks that had been hidden out of the high-ranking chimp’s line of sight. (Control experiments showed that if both animals saw where the food was hidden, the subordinate animal didn’t bother to approach the food.) The reasonable explanation was that the low-ranking chimp modeled his rival’s thought process in order to exploit his blind spots. He had a concept of what the other chimp saw and believed—the basic definition of theory of mind.

This study and others like it in 2000 and 2001 led the group to conclude that chimps do actually have insight into other individuals’ thoughts. But they don’t use this ability to cooperate, as humans often do. They use it to win.

“If you try to do something cooperative with a chimp—point out something, show them where some food is—their attention wanders all over the place,” says Tomasello. “But if you compete with them over food, they are zeroed in like a laser. All their cognitive skills are on.” (If chimps had a self-help bestseller, it would be titled, How to Outwit Rivals and Get More Fruit.)

It’s not that chimpanzees are incapable of helping. De Waal describes one instance in which chimps boosted an arthritic elderly troupe mate up to a joint perch and used their own mouths to carry water to her so that she could drink. De Waal says this is one of many examples of animal cooperation. He predicts the claim that humans are unique because they collaborate to solve problems “will drop by the wayside.”

Tomasello agrees that chimps sometimes assist each other and help each other get food, under specific conditions that eliminate all possibility of competition. In one of his experiments, conducted with wild-born chimps in a Ugandan sanctuary, two chimps entered separate cages, with fruit placed in a third. The first chimp knew from previous experience that he could not open his own cage door to get to the food, but he could help the other animal by pulling a chain that opened the door of the other cage. Here, with nothing to gain and nothing to lose, eight out of nine animals pulled the chain so that the other animal could get the fruit.

“It was a huge surprise to me,” Tomasello says. “My initial reaction was: Damn. That doesn’t fit very well.” But the more he thought about it, the more he realized that chimps, again, are acting individually, not in cooperation with each other. “To help, you just need to know what the goal is, and then if you’re motivated, you can help,” he says. “It’s not cognitively very complicated.” Human cooperation, meanwhile, requires two or more people to have insight into each other’s intentions, formulate a joint goal, assume specific roles, and then coordinate their efforts. It demands cognitive capacities that even the most helpful chimpanzees don’t possess.

In this case, the term “helpful” may be a little generous. Alicia Melis, a former postdoc in Tomasello’s lab, explains that chimps work together only grudgingly when it comes to obtaining food. In one of her experiments, a board laden with food is placed beyond the reach of two chimps; they can get the food only if each grabs one end of a rope attached to the board and they jointly pull it. In her experiment, the animals worked together only if the food was already evenly divided so that they did not have to compete over the spoils. It also helped if they already got along.

“The motivation does not seem to be, ‘Let’s do this together,’ ” says Melis, now an assistant professor of behavioral science at Warwick Business School in the U.K. “It’s, ‘Let me try to do this alone, and if I can’t, we’ll do it together.’ ”

Tomasello has discovered that young children, by contrast, find that working together can be a reward all its own. When adults deliberately drop objects in his experiments, babies of 14 months will crawl over to pick them up and hand them back. Toddlers open doors for experimenters whose hands are full. They do it without being asked and without being rewarded. Once they get the idea that they are partnering, they commit to joint intentionality. If a partner is having trouble, they stop and help. They share the spoils equally. “They really understand that we’re doing this together, and we have to divide it together,” Tomasello says.

Evolution of Collaboration

There are no fossils of ancient hominid brains or other physical evidence that might tell us when and how our ancestors first put their minds together to collaborate. Without such clues, the question of why we alone became a collaborative species is difficult to answer, says Hare, who is now a professor at the Center for Cognitive Neuroscience at Duke University. “Figuring out what makes us unique is hard as hell,” he says. “But it’s much easier than the next question, which is the real issue, the Higgs boson of evolutionary anthropology: How did we get that way?”

In the absence of physical evidence, Tomasello proposes one possible scenario. During the Pleistocene, about 1.5 million years ago, the climate became very bumpy, with frequent temperature swings that forced our ancestors to work together to access new sources of food. Perhaps we became scavengers, joining forces to ward off bigger, tougher meat-eating competitors. Under these circumstances, any genetic variation that made it easier to collaborate—maybe by more accurately reading someone else’s intentions, seeing the whites of their eyes, or simply being more relaxed about sharing food—presumably would have helped those individuals survive, and would have spread through the population.

Hints as to how this might have happened emerge from a surprising place: a fox-breeding farm in Siberia. In the 1950s the Russian biologist Dmitri Belyaev was interested in how dogs might first have been domesticated. He paired the most docile, friendly foxes he could find, then chose the gentlest from each litter and bred them. In a mere 10 generations, the young foxes acted like puppy dogs. The first time they met a human, they wagged their tails and tried to leap into people’s arms to lick their faces.

The descendants of those foxes still live in a facility in Siberia, where Hare, Tomasello’s former student, traveled in 2003 to test their cognition. He found that fox kits that had spent less than 20 minutes total around a person already understood human gestures, such as following a pointing finger to find food. They did not have to be taught. “That blew me away,” Hare says. His experiments suggested that as the foxes lost their fear of humans, they became able to repurpose their cognitive abilities to a new human-focused agenda: relating to us.

The foxes’ ability to read human social cues was now under strong artificial evolutionary pressure, since only the friendliest animals got the chance to breed. With Belyaev calling the shots, the foxes were competing against each other to be more socially perceptive. The outcome, a few dozen generations later, is a fox that understands human pointing. The small change in temperament permitted a big advance in social intelligence.

Hare and Tomasello suspect our ancestors went through a similar process. Basically, we domesticated ourselves. When collaborating to find food became essential because of changes in the climate or changes in the competition, we became less aggressive and more willing to share. Aggressive individuals, unwilling to cooperate, would starve and die out. Now that our temperaments allowed us to put our minds together, we were able to develop communal inventions like language and culture, and sustain these innovations by teaching and imitating one another. The ability to crystallize knowledge in inventions and traditions, Tomasello says, is what turned the ordinary primate mind into an extraordinary human one.

“Through our collaborative efforts, we have built our cultural worlds, and we are constantly adapting to them,” he writes in Why We Cooperate.

Us and Them

Today Tomasello is also looking through the prism of collaboration and beginning to explain some of the uniquely dark and nasty things that humans do. Maintaining a collaborative social structure encourages us to shun outsiders and discipline nonconformists. It fosters groupthink—the urge to stifle dissenting opinions in the interest of harmony and loyalty. Here, his research connects with that of anthropologists and economists who study social norms and other psychological underpinnings of group behavior.

Game theory models, which forecast how people behave when their interests are in conflict, suggest that cooperation can only be sustained in large groups if members punish anybody who freeloads or behaves selfishly. This prediction was borne out in 2005 by an anthropological study of 15 societies, mostly traditional small-scale communities, scattered around the globe.

But our tendency to enforce standards goes beyond simply ensuring justice. The impulse to formulate social rules and punish rule breakers applies to all kinds of situations, from whom we marry to how we dress. One possible benefit of these social norms is that they help us quickly identify who is part of our in-group and who is not; they also make it easier to collaborate more effectively. (If you hunt the same way I do, it’s going to be easier for us to work together, and it’s also a sign that you are a member of my group, someone I can presumably rely upon.)

The downside is that we also tend to blindly adopt arbitrary social conventions. Unlike other great apes, we are fundamentally conformists, Tomasello says. We form groups in which everybody dresses and talks the same way, “and anybody who intentionally doesn’t conform, we wonder: What’s wrong with them—do they not want to be one of us?” From this perspective, laws, morals, and religious rules are simply larger and more institutional versions of the impulse to police social norms, he says: “Human societies are just one layer of cooperation, or incentives for cooperation, on top of another.”

The open question is whether being natural-born collaborators also condemns us to be small-minded conformists who fear and distrust outsiders. Tomasello is now exploring how children understand group membership, testing how they act while wearing uniforms or being asked to work together. Kids absorb social norms quickly, he has found, and they enforce them enthusiastically. They can be little martinets. In one recent experiment, 3-year-olds are shown a game of pretend in which a pen is supposed to be used as an imaginary toothbrush. A puppet held by a researcher then asks to join the game, but draws with the pen instead. One child is outraged, barking, No! You must brush the teeth! The child’s reaction demonstrates the basic urge to impose social rules even when they are meaningless.

Ultimately, Tomasello’s research on human nature arrives at a paradox: our minds are the product of competitive intelligence and cooperative wisdom, our behavior a blend of brotherly love and hostility toward out-groups. Confronted by this paradox, the ugly side—the fact that humans compete, fight, and kill each other in wars—dismays most people, Tomasello says. And he agrees that our tendency to distrust outsiders—lending itself to prejudice, violence, and hate—should not be discounted or underestimated. But he says he is optimistic. In the end, what stands out more is our exceptional capacity for generosity and mutual trust, those moments in which we act like no species that has ever come before us.

Kat McGowan is a contributing editor at Discover magazine and independent journalist based in Berkeley, Calif., and New York City. She writes about neuroscience, genetics, and other science that affects how we understand ourselves.

This article was originally published in our “What Makes You So Special” issue in April, 2013.