October 1, 2009

Move over, Lucy. And kiss the missing link goodbye.

Scientists today announced the discovery of the oldest fossil skeleton of a human ancestor. The find reveals that our forebears underwent a previously unknown stage of evolution more than a million years before Lucy, the iconic early human ancestor specimen that walked the Earth 3.2 million years ago.

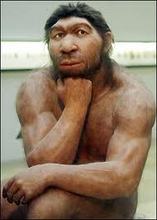

The centerpiece of a treasure trove of new fossils, the skeleton—assigned to a species called Ardipithecus ramidus—belonged to a small-brained, 110-pound (50-kilogram) female nicknamed "Ardi." (See pictures of Ardipithecus ramidus.)

The fossil puts to rest the notion, popular since Darwin's time, that a chimpanzee-like missing link—resembling something between humans and today's apes—would eventually be found at the root of the human family tree. Indeed, the new evidence suggests that the study of chimpanzee anatomy and behavior—long used to infer the nature of the earliest human ancestors—is largely irrelevant to understanding our beginnings.

Ardi instead shows an unexpected mix of advanced characteristics and of primitive traits seen in much older apes that were unlike chimps or gorillas (interactive: Ardi's key features). As such, the skeleton offers a window on what the last common ancestor of humans and living apes might have been like.

Announced at joint press conferences in Washington, D.C., and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, the analysis of the Ardipithecus ramidus bones will be published in a collection of papers tomorrow in a special edition of the journal Science, along with an avalanche of supporting materials published online.

"This find is far more important than Lucy," said Alan Walker, a paleontologist from Pennsylvania State University who was not part of the research. "It shows that the last common ancestor with chimps didn't look like a chimp, or a human, or some funny thing in between." (Related: "Oldest Homo Sapiens Fossils Found, Experts Say" [June 11, 2003].)

Ardi Surrounded by Family

The Ardipithecus ramidus fossils were discovered in Ethiopia's harsh Afar desert at a site called Aramis in the Middle Awash region, just 46 miles (74 kilometers) from where Lucy's species, Australopithecus afarensis, was found in 1974. Radiometric dating of two layers of volcanic ash that tightly sandwiched the fossil deposits revealed that Ardi lived 4.4 million years ago.

Older hominid fossils have been uncovered, including a skull from Chad at least six million years old and some more fragmentary, slightly younger remains from Kenya and nearby in the Middle Awash.

While important, however, none of those earlier fossils are nearly as revealing as the newly announced remains, which in addition to Ardi's partial skeleton include bones representing at least 36 other individuals.

"All of a sudden you've got fingers and toes and arms and legs and heads and teeth," said Tim White of the University of California, Berkeley, who co-directed the work with Berhane Asfaw, a paleoanthropologist and former director of the National Museum of Ethiopia, and Giday WoldeGabriel, a geologist at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico.

"That allows you to do something you can't do with isolated specimens," White said. "It allows you to do biology."

(Related: Rediscover the original Ardipithecus.)

Ardi's Weird Way of Moving

The biggest surprise about Ardipithecus's biology is its bizarre means of moving about.

All previously known hominids—members of our ancestral lineage—walked upright on two legs, like us. But Ardi's feet, pelvis, legs, and hands suggest she was a biped on the ground but a quadruped when moving about in the trees.

Her big toe, for instance, splays out from her foot like an ape's, the better to grasp tree limbs. Unlike a chimpanzee foot, however, Ardipithecus's contains a special small bone inside a tendon, passed down from more primitive ancestors, that keeps the divergent toe more rigid. Combined with modifications to the other toes, the bone would have helped Ardi walk bipedally on the ground, though less efficiently than later hominids like Lucy. The bone was lost in the lineages of chimps and gorillas.

According to the researchers, the pelvis shows a similar mosaic of traits. The large flaring bones of the upper pelvis were positioned so that Ardi could walk on two legs without lurching from side to side like a chimp. But the lower pelvis was built like an ape's, to accommodate huge hind limb muscles used in climbing.

Even in the trees, Ardi was nothing like a modern ape, the researchers say.

Modern chimps and gorillas have evolved limb anatomy specialized to climbing vertically up tree trunks, hanging and swinging from branches, and knuckle-walking on the ground.

While these behaviors require very rigid wrist bones, for instance, the wrists and finger joints of Ardipithecus were highly flexible. As a result Ardi would have walked on her palms as she moved about in the trees—more like some primitive fossil apes than like chimps and gorillas.

"What Ardi tells us is there was this vast intermediate stage in our evolution that nobody knew about," said Owen Lovejoy, an anatomist at Kent State University in Ohio, who analyzed Ardi's bones below the neck. "It changes everything."

Against All Odds, Ardi Emerges

The first, fragmentary specimens of Ardipithecus were found at Aramis in 1992 and published in 1994. The skeleton announced today was discovered that same year and excavated with the bones of the other individuals over the next three field seasons. But it took 15 years before the research team could fully analyze and publish the skeleton, because the fossils were in such bad shape.

After Ardi died, her remains apparently were trampled down into mud by hippos and other passing herbivores. Millions of years later, erosion brought the badly crushed and distorted bones back to the surface.

They were so fragile they would turn to dust at a touch. To save the precious fragments, White and colleagues removed the fossils along with their surrounding rock. Then, in a lab in Addis, the researchers carefully tweaked out the bones from the rocky matrix using a needle under a microscope, proceeding "millimeter by submillimeter," as the team puts it in Science. This process alone took several years.

Pieces of the crushed skull were then CT-scanned and digitally fit back together by Gen Suwa, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Tokyo.

In the end, the research team recovered more than 125 pieces of the skeleton, including much of the feet and virtually all of the hands—an extreme rarity among hominid fossils of any age, let alone one so very ancient.

"Finding this skeleton was more than luck," said White. "It was against all odds."

Ardi's World

The team also found some 6,000 animal fossils and other specimens that offer a picture of the world Ardi inhabited: a moist woodland very different from the region's current, parched landscape. In addition to antelope and monkey species associated with forests, the deposits contained forest-dwelling birds and seeds from fig and palm trees.

Wear patterns and isotopes in the hominid teeth suggest a diet that included fruits, nuts, and other forest foods.

If White and his team are right that Ardi walked upright as well as climbed trees, the environmental evidence would seem to strike the death knell for the "savanna hypothesis"—a long-standing notion that our ancestors first stood up in response to their move onto an open grassland environment.

Sex for Food

Some researchers, however, are unconvinced that Ardipithecus was quite so versatile.

"This is a fascinating skeleton, but based on what they present, the evidence for bipedality is limited at best," said William Jungers, an anatomist at Stony Brook University in New York State.

"Divergent big toes are associated with grasping, and this has one of the most divergent big toes you can imagine," Jungers said. "Why would an animal fully adapted to support its weight on its forelimbs in the trees elect to walk bipedally on the ground?"

One provocative answer to that question—originally proposed by Lovejoy in the early 1980s and refined now in light of the Ardipithecus discoveries—attributes the origin of bipedality to another trademark of humankind: monogamous sex.

Virtually all apes and monkeys, especially males, have long upper canine teeth—formidable weapons in fights for mating opportunities.

But Ardipithecus appears to have already embarked on a uniquely human evolutionary path, with canines reduced in size and dramatically "feminized" to a stubby, diamond shape, according to the researchers. Males and female specimens are also close to each other in body size.

Lovejoy sees these changes as part of an epochal shift in social behavior: Instead of fighting for access to females, a male Ardipithecus would supply a "targeted female" and her offspring with gathered foods and gain her sexual loyalty in return.

To keep up his end of the deal, a male needed to have his hands free to carry home the food. Bipedalism may have been a poor way for Ardipithecus to get around, but through its contribution to the "sex for food" contract, it would have been an excellent way to bear more offspring. And in evolution, of course, more offspring is the name of the game (more: "Did Early Humans Start Walking for Sex?").

Two hundred thousand years after Ardipithecus, another species called Australopithecus anamensis appeared in the region. By most accounts, that species soon evolved into Australopithecus afarensis, with a slightly larger brain and a full commitment to a bipedal way of life. Then came early Homo, with its even bigger brain and budding tool use.

Did primitive Ardipithecus undergo some accelerated change in the 200,000 years between it and Australopithecus—and emerge as the ancestor of all later hominids? Or was Ardipithecus a relict species, carrying its quaint mosaic of primitive and advanced traits with it into extinction?

Study co-leader White sees nothing about the skeleton "that would exclude it from ancestral status." But he said more fossils would be needed to fully resolve the issue.

Stony Brook's Jungers added, "These finds are incredibly important, and given the state of preservation of the bones, what they did was nothing short of heroic.

But this is just the beginning of the story."

Look for comprehensive coverage of Ardipithecus ramidus in a future issue of National Geographic magazine.