Today's Daily Om looks at the ways we can sometimes find ourselves off track in our lives -- and why that might happen.

A well-known American poet, Robert Frost, once famously said, "The only way out is through."Moving through Darkness

The Places We Go

by Madisyn Taylor

May 19, 2014

Often it takes something major to wake us up as we struggle to maintain an illusion of control.

In life, most of us want things to go to the places we have envisioned ourselves going. We have plans and visions, some of them divinely inspired, that we want to see through to completion. We want to be happy, successful, and healthy, all of which are perfectly natural and perfectly human. So when life takes us to places we didn’t consciously want to go, we often feel as if something has gone wrong, or we must have made a mistake somewhere along the line, or any number of other disheartening possibilities. This is just life’s way of taking us to a place we need to go for reasons that go deeper than our own ability to reason. These hard knocks and trials are designed to shed light on our unconscious workings and deepen our experience of reality.

Often it takes something major to wake us up, to shake us loose from our ego’s grip as it struggles to maintain an illusion of control. It is loss of control more than anything else that humbles us and enables us to see the big picture. It reminds us that the key to the universe lies in what we do not know, and what we do know is a small fraction of the great mystery in which we live. This awareness softens and lightens us, as we release our resistance to what is. Another gift gleaned from going to these seemingly undesirable places is that, in our response to difficulty, we can see all the patterns and unresolved emotional baggage that stand in the way of our unconditional joyfulness. Joy exists within us independently of whether things go our way or not. And when we don’t feel it, we can trust that we will find it if we are willing to surrender to the situation, moving through it as we move through our difficult feelings.

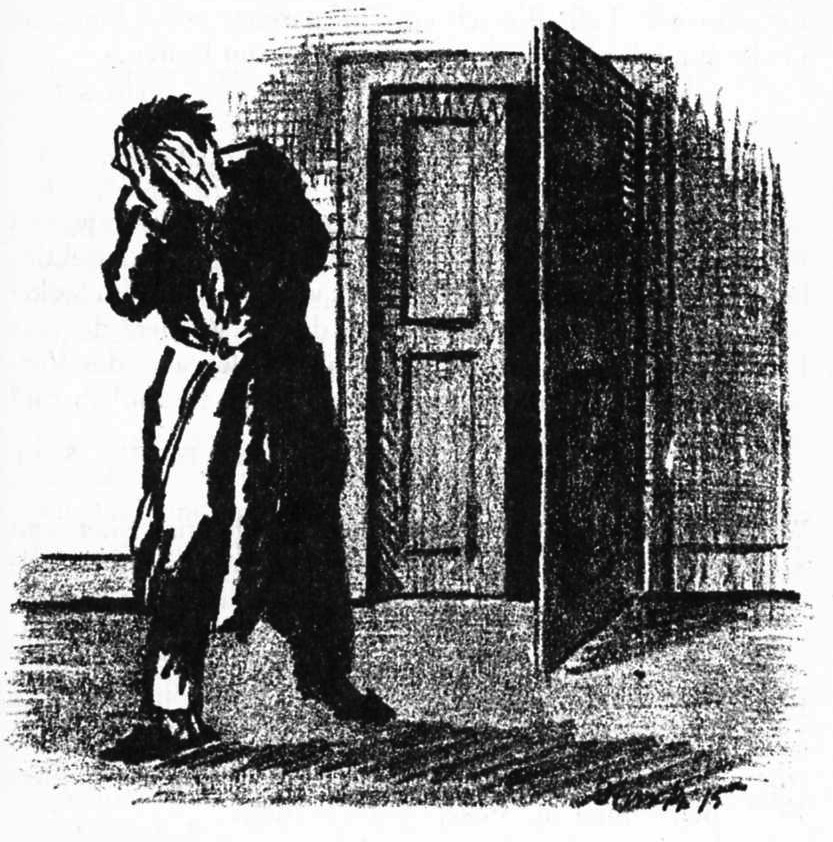

We can take our inspiration from any fairy tale that finds its central character lost in a dark wood, frightened and alone. We know that the journey through the wood provides its own kind of beauty and richness. On the other side, we will emerge transformed, lighter and brighter, braver and more confident for having moved through that darkness.

Very often, when we find ourselves far from where we wanted to be, either through mistakes we made or the simple ways that life can confound our expectations, there is a reason for the detour.

While we struggle with our loss of control, or self-criticism, we easily lose touch with the big picture. This is when it helps to have friends for support and encouragement, and some form of spiritual practice that can allow us to sit peacefully with our feelings of confusion.

If we do not allow the feelings, we never see the potential for growth that a tough situation provides. In doing so, we only compound the problem and put off dealing with it. The next time it comes up, it will be bigger and more challenging.

Often, if we are willing to listen, there is a quiet voice within us that can help us find our way out of the darkness. But we have to listen.