In this piece by Gaia Vince, the role of the vagus nerve in physical issues, such as autoimmune disorders is examined. Controlling inflammation through vagal stimulation could be a HUGE breakthrough in treating nearly all forms of disease (which are inflammatory illnesses at the molecular level).

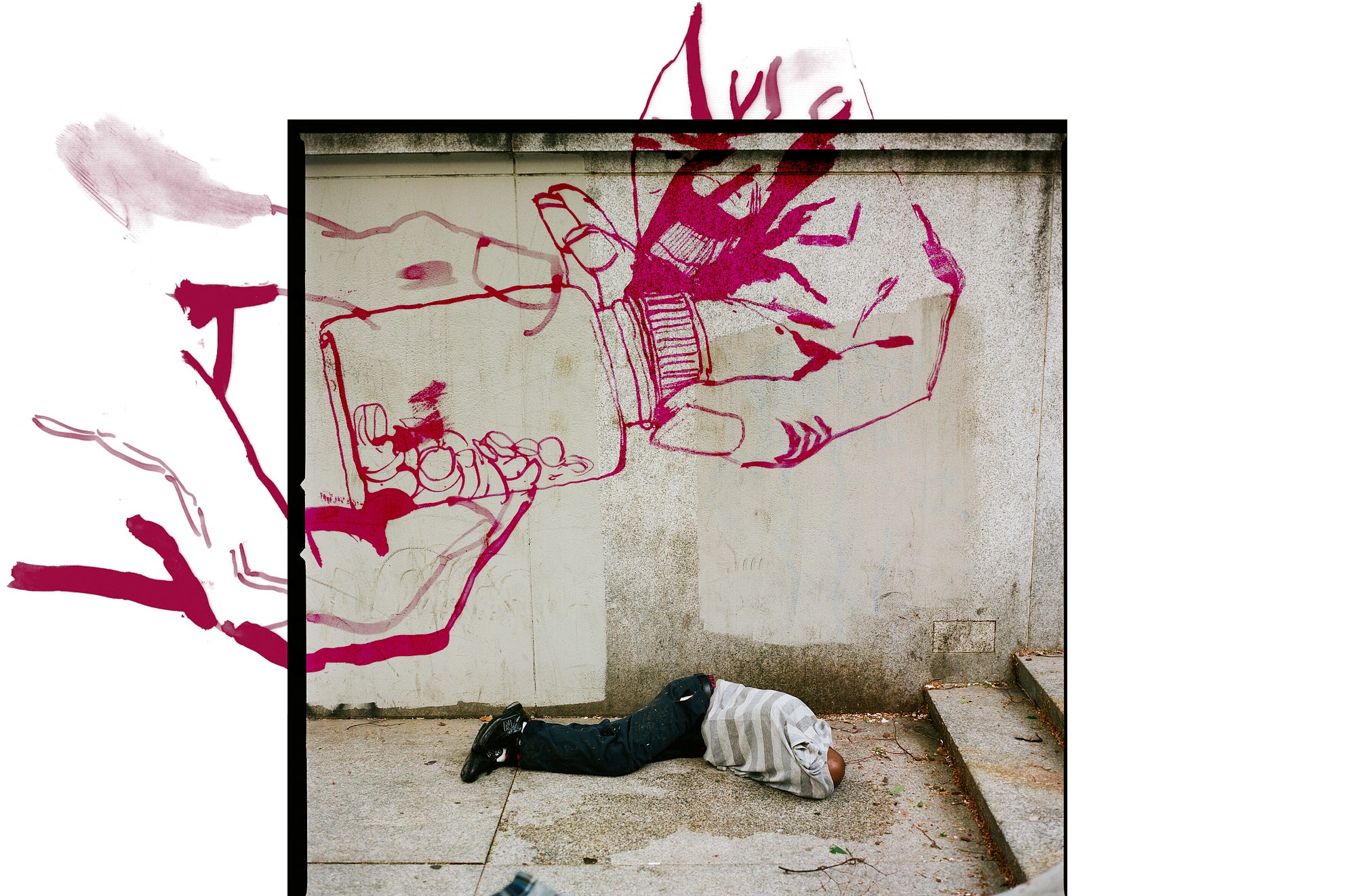

© Job BootHacking the nervous system

One nerve connects your vital organs, sensing and shaping your health. If we learn to control it, the future of medicine will be electric.

By Gaia Vince.

When Maria Vrind, a former gymnast from Volendam in the Netherlands, found that the only way she could put her socks on in the morning was to lie on her back with her feet in the air, she had to accept that things had reached a crisis point. “I had become so stiff I couldn’t stand up,” she says. “It was a great shock because I’m such an active person.”

It was 1993. Vrind was in her late 40s and working two jobs, athletics coach and a carer for disabled people, but her condition now began taking over her life. “I had to stop my jobs and look for another one as I became increasingly disabled myself.” By the time she was diagnosed, seven years later, she was in severe pain and couldn’t walk any more. Her knees, ankles, wrists, elbows and shoulder joints were hot and inflamed. It was rheumatoid arthritis, a common but incurable autoimmune disorder in which the body attacks its own cells, in this case the lining of the joints, producing chronic inflammation and bone deformity.

Waiting rooms outside rheumatoid arthritis clinics used to be full of people in wheelchairs. That doesn’t happen as much now because of a new wave of drugs called biopharmaceuticals – such as highly targeted, genetically engineered proteins – which can really help. Not everyone feels better, however: even in countries with the best healthcare, at least 50 per cent of patients continue to suffer symptoms.

Like many patients, Vrind was given several different medications, including painkillers, a cancer drug called methotrexate to dampen her entire immune system, and biopharmaceuticals to block the production of specific inflammatory proteins. The drugs did their job well enough – at least, they did until one day in 2011, when they stopped working.

“I was on holiday with my family and my arthritis suddenly became terrible and I couldn’t walk – my daughter-in-law had to wash me.” Vrind was rushed to hospital, where she was hooked up to an intravenous drip and given another cancer drug, one that targeted her white blood cells. “It helped,” she admits, but she was nervous about relying on such a drug long-term.

Luckily, she would not have to. As she was resigning herself to a life of disability and monthly chemotherapy, a new treatment was being developed that would profoundly challenge our understanding of how the brain and body interact to control the immune system. It would open up a whole new approach to treating rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases, using the nervous system to modify inflammation. It would even lead to research into how we might use our minds to stave off disease.

And, like many good ideas, it came from an unexpected source.

© Job Boot

The nerve hunter

Kevin Tracey, a neurosurgeon based in New York, is a man haunted by personal events – a man with a mission. “My mother died from a brain tumour when I was five years old. It was very sudden and unexpected,” he says. “And I learned from that experience that the brain – nerves – are responsible for health.” This drove his decision to become a brain surgeon. Then, during his hospital training, he was looking after a patient with serious burns who suddenly suffered severe inflammation. “She was an 11-month-old baby girl called Janice who died in my arms.”

These traumatic moments made him a neurosurgeon who thinks a lot about inflammation. He believes it was this perspective that enabled him to interpret the results of an accidental experiment in a new way.

In the late 1990s, Tracey was experimenting with a rat’s brain. “We’d injected an anti-inflammatory drug into the brain because we were studying the beneficial effect of blocking inflammation during a stroke,” he recalls. “We were surprised to find that when the drug was present in the brain, it also blocked inflammation in the spleen and in other organs in the rest of the body. Yet the amount of drug we’d injected was far too small to have got into the bloodstream and travelled to the rest of the body.”After months puzzling over this, he finally hit upon the idea that the brain might be using the nervous system – specifically the vagus nerve – to tell the spleen to switch off inflammation everywhere.

It was an extraordinary idea – if Tracey was right, inflammation in body tissues was being directly regulated by the brain. Communication between the immune system’s specialist cells in our organs and bloodstream and the electrical connections of the nervous system had been considered impossible. Now Tracey was apparently discovering that the two systems were intricately linked.

The first critical test of this exciting hypothesis was to cut the vagus nerve. When Tracey and his team did, injecting the anti-inflammatory drug into the brain no longer had an effect on the rest of the body. The second test was to stimulate the nerve without any drug in the system. “Because the vagus nerve, like all nerves, communicates information through electrical signals, it meant that we should be able to replicate the experiment by putting a nerve stimulator on the vagus nerve in the brainstem to block inflammation in the spleen,” he explains. “That’s what we did and that was the breakthrough experiment.”

© Job Boot

The wandering nerve

The vagus nerve starts in the brainstem, just behind the ears. It travels down each side of the neck, across the chest and down through the abdomen. ‘Vagus’ is Latin for ‘wandering’ and indeed this bundle of nerve fibres roves through the body, networking the brain with the stomach and digestive tract, the lungs, heart, spleen, intestines, liver and kidneys, not to mention a range of other nerves that are involved in speech, eye contact, facial expressions and even your ability to tune in to other people’s voices. It is made of thousands and thousands of fibres and 80 per cent of them are sensory, meaning that the vagus nerve reports back to your brain what is going on in your organs.

Operating far below the level of our conscious minds, the vagus nerve is vital for keeping our bodies healthy. It is an essential part of the parasympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for calming organs after the stressed ‘fight-or-flight’ adrenaline response to danger. Not all vagus nerves are the same, however: some people have stronger vagus activity, which means their bodies can relax faster after a stress.

The strength of your vagus response is known as your vagal tone and it can be determined by using an electrocardiogram to measure heart rate. Every time you breathe in, your heart beats faster in order to speed the flow of oxygenated blood around your body. Breathe out and your heart rate slows. This variability is one of many things regulated by the vagus nerve, which is active when you breathe out but suppressed when you breathe in, so the bigger your difference in heart rate when breathing in and out, the higher your vagal tone.

Research shows that a high vagal tone makes your body better at regulating blood glucose levels, reducing the likelihood of diabetes, stroke and cardiovascular disease. Low vagal tone, however, has been associated with chronic inflammation. As part of the immune system, inflammation has a useful role helping the body to heal after an injury, for example, but it can damage organs and blood vessels if it persists when it is not needed. One of the vagus nerve’s jobs is to reset the immune system and switch off production of proteins that fuel inflammation. Low vagal tone means this regulation is less effective and inflammation can become excessive, such as in Maria Vrind’s rheumatoid arthritis or in toxic shock syndrome, which Kevin Tracey believes killed little Janice.

Having found evidence of a role for the vagus in a range of chronic inflammatory diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, Tracey and his colleagues wanted to see if it could become a possible route for treatment. The vagus nerve works as a two-way messenger, passing electrochemical signals between the organs and the brain. In chronic inflammatory disease, Tracey figured, messages from the brain telling the spleen to switch off production of a particular inflammatory protein, tumour necrosis factor (TNF), weren’t being sent. Perhaps the signals could be boosted?

He spent the next decade meticulously mapping all the neural pathways involved in regulating TNF, from the brainstem to the mitochondria inside all our cells. Eventually, with a robust understanding of how the vagus nerve controlled inflammation, Tracey was ready to test whether it was possible to intervene in human disease.

© Job Boot

Stimulating trial

In the summer of 2011, Maria Vrind saw a newspaper advertisement calling for people with severe rheumatoid arthritis to volunteer for a clinical trial. Taking part would involve being fitted with an electrical implant directly connected to the vagus nerve. “I called them immediately,” she says. “I didn’t want to be on anticancer drugs my whole life; it’s bad for your organs and not good long-term.”

Tracey had designed the trial with his collaborator, Paul-Peter Tak, professor of rheumatology at the University of Amsterdam. Tak had long been searching for an alternative to strong drugs that suppress the immune system to treat rheumatoid arthritis. “The body’s immune response only becomes a problem when it attacks your own body rather than alien cells, or when it is chronic,” he reasoned. “So the question becomes: how can we enhance the body’s switch-off mechanism? How can we drive resolution?”

When Tracey called him to suggest stimulating the vagus nerve might be the answer by switching off production of TNF, Tak quickly saw the potential and was enthusiastic to see if it would work. Vagal nerve stimulation had already been approved in humans for epilepsy, so getting approval for an arthritis trial would be relatively straightforward. A more serious potential hurdle was whether people used to taking drugs for their condition would be willing to undergo an operation to implant a device inside their body: “There was a big question mark about whether patients would accept a neuroelectric device like a pacemaker,” Tak says.

He needn’t have worried. More than a thousand people expressed interest in the procedure, far more than were needed for the trial. In November 2011, Vrind was the first of 20 Dutch patients to be operated on.

“They put the pacemaker on the left-hand side of my chest, with wires that go up and attach to the vagus nerve in my throat,” she says. “I waited two weeks while the area healed, and then the doctors switched it on and adjusted the settings for me.”

She was given a magnet to swipe across her throat six times a day, activating the implant and stimulating her vagus nerve for 30 seconds at a time. The hope was that this would reduce the inflammatory response in her spleen. As Vrind and the other trial participants were sent home, it became a waiting game for Tracey, Tak and the team to see if the theory, lab studies and animal trials would bear fruit in real patients. “We hoped that for some, there would be an easing of their symptoms – perhaps their joints would become a little less painful,” Tak says.

At first, Vrind was a bit too eager for a miracle cure. She immediately stopped taking her pills, but her symptoms came back so badly that she was bedridden and in terrible pain. She went back on the drugs and they were gradually reduced over a week instead.

And then the extraordinary happened: Vrind experienced a recovery more remarkable than she or the scientists had dared hope for.

“Within a few weeks, I was in a great condition,” she says. “I could walk again and cycle, I started ice-skating again and got back to my gymnastics. I feel so much better.” She is still taking methotrexate, which she will need at a low dose for the rest of her life, but at 68, semi-retired Vrind now plays and teaches seniors’ volleyball a couple of hours a week, cycles for at least an hour every day, does gymnastics, and plays with her eight grandchildren.

Other patients on the trial had similar transformative experiences. The results are still being prepared for publication but Tak says more than half of the patients showed significant improvement and around one-third are in remission – in effect cured of their rheumatoid arthritis. Sixteen of the 20 patients on the trial not only felt better, but measures of inflammation in their blood also went down. Some are now entirely drug-free. Even those who have not experienced clinically significant improvements with the implant insist it helps them; nobody wants it removed.

“We have shown very clear trends with stimulation of three minutes a day,” Tak says. “When we discontinued stimulation, you could see disease came back again and levels of TNF in the blood went up. We restarted stimulation, and it normalised again.”

Tak suspects that patients will continue to need vagal nerve stimulation for life. But unlike the drugs, which work by preventing production of immune cells and proteins such as TNF, vagal nerve stimulation seems to restore the body’s natural balance. It reduces the over-production of TNF that causes chronic inflammation but does not affect healthy immune function, so the body can respond normally to infection.

“I’m really glad I got into the trial,” says Vrind. “It’s been more than three years now since the implant and my symptoms haven’t returned. At first I felt a pain in my head and throat when I used it, but within a couple of days, it stopped. Now I don’t feel anything except a tightness in my throat and my voice trembles while it’s working.

“I have occasional stiffness or a little pain in my knee sometimes but it’s gone in a couple of hours. I don’t have any side-effects from the implant, like I had with the drugs, and the effect is not wearing off, like it did with the drugs.”

© Job Boot

Raising the tone

Having an electrical device surgically implanted into your neck for the rest of your life is a serious procedure. But the technique has proved so successful – and so appealing to patients – that other researchers are now looking into using vagal nerve stimulation for a range of other chronic debilitating conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease, asthma, diabetes, chronic fatigue syndrome and obesity.

But what about people who just have low vagal tone, whose physical and mental health could benefit from giving it a boost? Low vagal tone is associated with a range of health risks, whereas people with high vagal tone are not just healthier, they’re also socially and psychologically stronger – better able to concentrate and remember things, happier and less likely to be depressed, more empathetic and more likely to have close friendships.

Twin studies show that to a certain extent, vagal tone is genetically predetermined – some people are born luckier than others. But low vagal tone is more prevalent in those with certain lifestyles – people who do little exercise, for example. This led psychologists at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to wonder if the relationship between vagal tone and wellbeing could be harnessed without the need for implants.

In 2010, Barbara Fredrickson and Bethany Kok recruited around 70 university staff members for an experiment. Each volunteer was asked to record the strength of emotions they felt every day. Vagal tone was measured at the beginning of the experiment and at the end, nine weeks later. As part of the experiment, half of the participants were taught a meditation technique to promote feelings of goodwill towards themselves and others.

Those who meditated showed a significant rise in vagal tone, which was associated with reported increases in positive emotions. “That was the first experimental evidence that if you increased positive emotions and that led to increased social closeness, then vagal tone changed,” Kok says.

Now at the Max Planck Institute in Germany, Kok is conducting a much larger trial to see if the results they found can be replicated. If so, vagal tone could one day be used as a diagnostic tool. In a way, it already is. “Hospitals already track heart-rate variability – vagal tone – in patients that have had a heart attack,” she says, “because it is known that having low variability is a risk factor.”

The implications of being able to simply and cheaply improve vagal tone, and so relieve major public health burdens such as cardiovascular conditions and diabetes, are enormous. It has the potential to completely change how we view disease. If visiting your GP involved a check on your vagal tone as easily as we test blood pressure, for example, you could be prescribed therapies to improve it. But this is still a long way off: “We don’t even know yet what a healthy vagal tone looks like,” cautions Kok. “We’re just looking at ranges, we don’t have precise measurements like we do for blood pressure.”

What seems more likely in the shorter term is that devices will be implanted for many diseases that today are treated by drugs: “As the technology improves and these devices get smaller and more precise,” says Kevin Tracey, “I envisage a time where devices to control neural circuits for bioelectronic medicine will be injected – they will be placed either under local anaesthesia or under mild sedation.”

However the technology develops, our understanding of how the body manages disease has changed for ever. “It’s become increasingly clear that we can’t see organ systems in isolation, like we did in the past,” says Paul-Peter Tak. “We just looked at the immune system and therefore we have medicines that target the immune system.

“But it’s very clear that the human is one entity: mind and body are one. It sounds logical but it’s not how we looked at it before. We didn’t have the science to agree with what may seem intuitive. Now we have new data and new insights.”

And Maria Vrind, who despite severe rheumatoid arthritis can now cycle pain-free around Volendam, has a new lease of life: “It’s not a miracle – they told me how it works through electrical impulses – but it feels magical. I don’t want them to remove it ever. I have my life back!”