Hello readers. I've been on vacation for the last several days. Here's an old post from my previous blog WhyWeReason.com to fill the void. It's about a paper by the NYU neuroscientists Joseph LeDoux, who argues that cognitive science needs to rethink how it understands emotions.

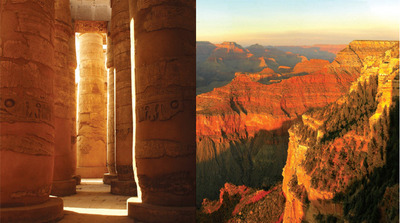

In Phaedrus, Plato likens the mind to a charioteer who commands two

horses, one that is irrational and crazed and another that is noble and

of good stock. The job of the charioteer is to control the horses to

proceed towards Enlightenment and the truth.

Plato’s allegory sparked an idea that perpetuated throughout the next

several millennia in western thought: emotion gets in the way of

reason. This makes sense to us. When people act out-of-order, they’re

irrational. No one was ever accused of being too reasonable. Around the

17

th and 18

th centuries, however, thinkers began

to challenge this idea. David Hume turned the tables on Plato: reason,

Hume said, was the slave of the passions. Psychological research of the

last few decades not only confirms this view, some of it suggests that

emotion is better at deciding.

We know a lot more about how the brain works compared to the ancient Greeks, but a decade into the 21

stcentury researchers are still debating which of Plato’s horses is in control, and which one we should listen to.

A couple of recent studies are shedding new light on this age-old discourse. The

first comes

from Michael Pham and his team at Columbia Business School. The

researchers asked participants to make predictions about eight different

outcomes ranging from American Idol finalists, to the winners of the

2008 Democratic primary, to the winner of the BCS championship

game. They also forecasted the Dow Jones average.

Pham created two groups. He told the first group to go with their

guts and the second to think it through. The results were telling. In

the American Idol results, for example, the first group correctly

predicted the winner 41 percent of the time whereas the second group was

only correct 24 percent of the time. The high-trust-in-feeling subjects

even predicted the stock market better.

Pham and his team conclude the following:

Results from eight studies show that individuals who had higher trust

in their feelings were better able to predict the outcome of a wide

variety of future events than individuals who had lower trust in their

feelings…. The fact that this phenomenon was observed in eight different

studies and with a variety of prediction contexts suggests that this

emotional oracle effect is a reliable and generalizable phenomenon. In

addition, the fact that the phenomenon was observed both when people

were experimentally induced to trust or not trust their feelings and

when their chronic tendency to trust or not trust their feelings was

simply measured suggests that the findings are not due to any

peculiarity of the main manipulation.

Does this mean we should always trust our intuition? It depends. A

recent study by Maarten Bos and his team identified an important nuance

when it comes to trusting our feelings. They asked one hundred and

fifty-six students to abstain from eating or drinking (sans water) for

three hours before the study. When they arrived Bos divided his

participants into two groups: one that consumed a sugary can of 7-Up and

another that drank a sugar-free drink.

After waiting a few minutes to let the sugar reach the brain the

students assessed four cars and four jobs, each with 12 key aspects that

made them more or less appealing (Bos designed the study so an optimal

choice was clear so he could measure of how well they decided). Next,

half of the subjects in each group spent four minutes either thinking

about the jobs and cars (the conscious thought condition) or watching a

wildlife film (to prevent them from consciously thinking about the jobs

and cars).

Here’s the BPS Research Digest on the

results:

For the participants with low sugar, their ratings were more astute

if they were in the unconscious thought condition, distracted by the

second nature film. By contrast, the participants who’d had the benefit

of the sugar hit showed more astute ratings if they were in the

conscious thought condition and had had the chance to think deliberately

for four minutes. ‘We found that when we have enough energy, conscious

deliberation enables us to make good decisions,’ the researchers said.

‘The unconscious on the other hand seems to operate fine with low

energy.’

So go with your gut if your energy is low. Otherwise, listen to your rational horse.

Here’s where things get difficult. By now the debate over the role

reason and emotion play in decision-making is well documented.

Psychologists have written thousands of papers on the subject. It shows

in the popular literature as well. From Antonio Damasio’s

Descartes’ Error to Daniel Kahneman’s

Thinking, Fast and Slow, the lay audience knows about both the power of thinking without thinking and their predictable irrationalities.

But what exactly is being debated? What do psychologists mean when

they talk about emotion and reason? Joseph LeDoux, author of popular

neuroscience books including

The Emotional Brain and

The Synaptic Self, recently published a

paper in

the journal Neuron that flips the whole debate on its head. “There is

little consensus about what emotion is and how it differs from other

aspects of mind and behavior, in spite of discussion and debate that

dates back to the earliest days in modern biology and psychology.” Yes,

what we call emotion roughly correlates with certain parts of the brain,

it is usually associated with activity in the amygdala and other

systems. But we might be playing a language game, and neuroscientists

are reaching a point where an understanding of the brain requires more

sophisticated language.

As LeDoux sees it, “If we don’t have an agreed-upon definition of

emotion that allows us to say what emotion is… how can we study emotion

in animals or humans, and how can we make comparisons between species?”

The short answer, according to the NYU professor, is “we fake it.”

With this in mind LeDoux introduces a new term to replace emotion: survival circuits. Here’s how he explains it:

The survival circuit concept provides a conceptualization of an

important set of phenomena that are often studied under the rubric of

emotion—those phenomena that reflect circuits and functions that are

conserved across mammals. Included are circuits responsible for defense,

energy/nutrition management, fluid balance, thermoregulation, and

procreation, among others. With this approach, key phenomena relevant to

the topic of emotion can be accounted for without assuming that the

phenomena in question are fundamentally the same or even similar to the

phenomena people refer to when they use emotion words to characterize

subjective emotional feelings (like feeling afraid, angry, or sad). This

approach shifts the focus away from questions about whether emotions

that humans consciously experience (feel) are also present in other

mammals, and toward questions about the extent to which circuits and

corresponding functions that are relevant to the field of emotion and

that are present in other mammals are also present in humans. And by

reassembling ideas about emotion, motivation, reinforcement, and arousal

in the context of survival circuits, hypotheses emerge about how

organisms negotiate behavioral interactions with the environment in

process of dealing with challenges and opportunities in daily life.

Needless to say, LeDoux’s paper changes things. Because emotion is an

unworkable term for science, neuroscientists and psychologists will

have to understand the brain on new terms. And when it comes to the

reason-emotion debate – which of Plato’s horses we should trust – they

will have to rethink certain assumptions and claims. The difficult part

is that we humans, by our very nature, cannot help but resort to folk

psychology to explain the brain. We deploy terms like soul, intellect,

reason, intuition and emotion but these words describe very little. Can

we understand the brain even though our words may never suffice? The

future of cognitive science might depend on it.