Researchers in England have identified a possible mechanism for how psilocybin (the natural, hallucinogenic tryptamine found in various mushroom species) affects its actions in the brain.

Turns out that the state of consciousness while "tripping" is quite similar to the state of consciousness while dreaming. And now everyone who has ever used hallucinogens is releasing a collective, "Duh!"

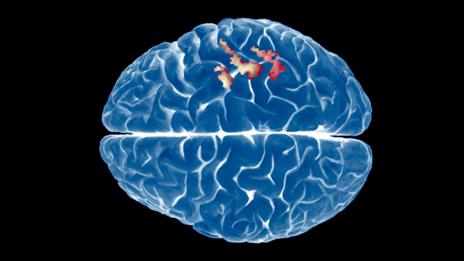

Using brain imaging technology, the researchers identified "

increased activity in the hippocampus and anterior cingulate cortex, areas involved in emotions and the formation of memories," areas considered to be more primitive in that they develop earlier. Meanwhile, there was "

decreased activity was seen in 'less primitive' regions of the brain associated with self-control and higher thinking, such as the thalamus, posterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex."

The chemical psilocybin causes the same brain activation as dreaming does

(Image: Ryan Wendler/Corbis)

Anyone who has enjoyed a magical mystery tour thanks to the psychedelic powers of magic mushrooms knows the experience is surreally dreamlike. Now neuroscientists have uncovered a reason why: the active ingredient, psilocybin, induces changes in the brain that are eerily akin to what goes on when we're off in the land of nod.

For the first time, we have a physical representation of what taking magic mushrooms does to the brain, says Robin Carhart-Harris of Imperial College London, who was part of the team who carried out the research.

Researchers from Imperial and Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany, injected 15 people with liquid psilocybin while they were lying in an fMRI scanner. The scans show the flow of blood through different regions of the brain, giving a measure of how active the different areas are.

The images taken while the volunteers were under the influence of the drug were compared with those taken when the same people were injected with an inert placebo. This revealed that during the psilocybin trip, there was increased activity in the hippocampus and anterior cingulate cortex, areas involved in emotions and the formation of memories. These are often referred to as primitive areas of the brain because they were some of the first parts to evolve.

Primal depths

At the same time, decreased activity was seen in "less primitive" regions of the brain associated with self-control and higher thinking, such as the thalamus, posterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex.

This activation pattern is similar to what is seen when someone is dreaming.

"This was neat because it fits the idea that psychedelics increase your emotional range," says Carhart-Harris.

Neuroscientific nuts and bolts aside, the findings could have genuine practical applications, says psychiatrist Adam Winstock at the Maudsley Hospital and Lewisham Drug and Alcohol Service in London. Psilocybin – along with other psychedelics – could be used therapeutically because of its capacity to probe deep into the primal corners of the brain.

"Dreaming appears to be an essential vehicle for unconscious emotional processing and learning," says Winstock. By using psilocybin to enter a dreamlike state, people could deal with stresses of trauma or depression, he says. "It could help suppress all the self-deceiving noise that impedes our ability to change and grow."

Next, the team wants to explore the potential use of magic mushrooms, LSD and other psychedelics to treat depression.

Journal reference: Human Brain Mapping, DOI: 10.1002/hbm.22562

* * * * *

Here is the abstract and introduction to the full article, which is freely available online.

Full Citation:

Tagliazucchi, E., Carhart-Harris, R., Leech, R., Nutt, D. and Chialvo, D. R. (2014, Jul 2). Enhanced repertoire of brain dynamical states during the psychedelic experience. Human Brain Mapping; ePub ahead of print. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22562

Enzo Tagliazucchi, Robin Carhart-Harris, Robert Leech, David Nutt, and Dante R. Chialvo

Article first published online: 2 JUL 2014

Abstract

The study of rapid changes in brain dynamics and functional connectivity (FC) is of increasing interest in neuroimaging. Brain states departing from normal waking consciousness are expected to be accompanied by alterations in the aforementioned dynamics. In particular, the psychedelic experience produced by psilocybin (a substance found in “magic mushrooms”) is characterized by unconstrained cognition and profound alterations in the perception of time, space and selfhood. Considering the spontaneous and subjective manifestation of these effects, we hypothesize that neural correlates of the psychedelic experience can be found in the dynamics and variability of spontaneous brain activity fluctuations and connectivity, measurable with functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI). Fifteen healthy subjects were scanned before, during and after intravenous infusion of psilocybin and an inert placebo. Blood-Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) temporal variability was assessed computing the variance and total spectral power, resulting in increased signal variability bilaterally in the hippocampi and anterior cingulate cortex. Changes in BOLD signal spectral behavior (including spectral scaling exponents) affected exclusively higher brain systems such as the default mode, executive control, and dorsal attention networks. A novel framework enabled us to track different connectivity states explored by the brain during rest. This approach revealed a wider repertoire of connectivity states post-psilocybin than during control conditions. Together, the present results provide a comprehensive account of the effects of psilocybin on dynamical behavior in the human brain at a macroscopic level and may have implications for our understanding of the unconstrained, hyper-associative quality of consciousness in the psychedelic state.

INTRODUCTION

Psilocybin (phophoryl-4-hydroxy-dimethyltryptamine) is the phosphorylated ester of the main psychoactive compound found in magic mushrooms. Pharmacologically related to the prototypical psychedelic LSD, psilocybin has a long history of ceremonial use via mushroom ingestion and, in modern times, psychedelics have been assessed as tools to enhance the psychotherapeutic process [Grob et al., 2011; Krebs et al., 2012; Moreno et al., 2006]. The subjective effects of psychedelics include (but are not limited to) unconstrained, hyperassociative cognition, distorted sensory perception (including synesthesia and visions of dynamic geometric patterns) and alterations in one's sense of self, time and space. There is recent preliminary evidence that psychedelics may be effective in the treatment of anxiety related to dying [Grob et al., 2011] and obsessive compulsive disorder [Moreno et al., 2006] and there are neurobiological reasons to consider their potential as antidepressants [Carhart-Harris et al., 2012, 2013]. Similar to ketamine (another novel candidate antidepressant) psychedelics may also mimic certain psychotic states such as the altered quality of consciousness that is sometimes seen in the onset-phase of a first psychotic episode [Carhart-Harris et al., 2014]. There is also evidence to consider similarities between the psychology and neurobiology of the psychedelic state and Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep [Carhart-Harris, 2007; Carhart-Harris and Nutt, 2014], the sleep stage associated with vivid dreaming [Aserinsky and Kleitman, 1953].

The potential therapeutic use of psychedelics, as well as their capacity to modulate the quality of conscious experience in a relatively unique and profound manner, emphasizes the importance of studying these drugs and how they act on the brain to produce their novel effects. One potentially powerful way to approach this problem is to exploit human neuroimaging to measure changes in brain activity during the induction of the psychedelic state. The neural correlates of the psychedelic experience induced by psilocybin have been recently assessed using Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) and BOLD fMRI [Carhart-Harris et al., 2012]. This work found that psilocybin results in a reduction of both CBF and BOLD signal in major subcortical and cortical hub structures such as the thalamus, posterior cingulate (PCC) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and in decreased resting state functional connectivity (RSFC) between the normally highly coupled mPFC and PCC. Furthermore, our most recent study used magnetoencephalography (MEG) to more directly measure altered neural activity post-psilocybin and here we found decreased oscillatory power in the same cortical hub structures [Muthukumaraswamy et al., 2013, see also Carhart-Harris et al., 2014 for a review on this work).

These results establish that psilocybin markedly affects BOLD, CBF, RSFC, and oscillatory electrophysiological measures in strategically important brain structures, presumably involved in information integration and routing [Carhart-Harris et al., 2014; de Pasquale et al., 2012; Hagmann et al., 2008; Leech et al., 2012]. However, the effects of psilocybin on the variance of brain activity parameters across time has been relatively understudied and this line of enquiry may be particularly informative in terms of shedding new light on the mechanisms by which psychedelics elicit their characteristic psychological effects. Thus, the main objective of this article is to examine how psilocybin modulates the dynamics and temporal variability of resting state BOLD activity. Once regarded as physiological noise, a large body of research has now established that resting state fluctuations in brain activity have enormous neurophysiological and functional relevance [Fox and Raichle, 2007]. Spontaneous fluctuations self-organize into internally coherent spatiotemporal patterns of activity that reflect neural systems engaged during distinct cognitive states (termed “intrinsic” or “resting state networks”—RSNs) [Fox and Raichle, 2005; Raichle, 2011; Smith et al., 2009]. It has been suggested that the variety of spontaneous activity patterns that the brain enters during task-free conditions reflects the naturally itinerant and variegated quality of normal consciousness [Raichle, 2011]. However, spatio-temporal patterns of resting state activity are globally well preserved in states such as sleep [Boly et al., 2008, 2012; Brodbeck et al., 2012; Larson-Prior et al., 2009; Tagliazucchi et al., a,b,c] in which there is a reduced level of awareness—although very specific changes in connectivity occur across NREM sleep, allowing the decoding of the sleep stage from fMRI data [Tagliazucchi et al., 2012c; Tagliazucchi and Laufs, 2014]. Thus, if the subjective quality of consciousness is markedly different in deep sleep relative to the normal wakeful state (for example) yet FC measures remain largely preserved, this would suggest that these measures provide limited information about the biological mechanisms underlying different conscious states. Similarly, intra-RSN FC is decreased under psilocybin [Carhart-Harris et al., 2013] yet subjective reports of unconstrained or even “expanded” consciousness are common among users (see Carhart-Harris et al. [2014] for a discussion). Thus, the present analyses are motivated by the view that more sensitive and specific indices are required to develop our understanding of the neurobiology of conscious states, and that measures which factor in variance over time may be particularly informative.

A key feature of spontaneous brain activity is its dynamical nature. In analogy to other self-organized systems in nature, the brain has been described as a system residing in (or at least near to) a critical point or transition zone between states of order and disorder [Chialvo, 2010; Haimovici et al., 2013; Tagliazucchi and Chialvo, 2011; Tagliazucchi et al., 2012a]. In this critical zone, it is hypothesized that the brain can explore a maximal repertoire of its possible dynamical states, a feature which could confer obvious evolutionary advantages in terms of cognitive and behavioral flexibility. It has even been proposed that this cognitive flexibility and range may be a key property of adult human consciousness itself [Tononi, 2012]. An interesting research question therefore is whether changes in spontaneous brain activity produced by psilocybin are consistent with a displacement from this critical point—perhaps towards a more entropic or super-critical state (i.e. one closer to the extreme of disorder than normal waking consciousness) [Carhart-Harris et al., 2014]. Further motivating this hypothesis are subjective reports of hyper-associative cognition under psychedelics, indicative of unconstrained brain dynamics. Thus, in order to test this hypothesis, it makes conceptual sense to focus on variability in activity and FC parameters over time, instead of the default procedure of averaging these over a prolonged period. In what follows, we present empirical data that tests the hypothesis that brain activity becomes less ordered in the psychedelic state and that the repertoire of possible states is enhanced. After the relevant findings have been presented, we engage in a discussion to suggest possible strategies that may further characterize quantitatively where the “psychedelic brain” resides in state space relative to the dynamical position occupied by normal waking consciousness.