This article looks at a little bit of the research currently being conducted and how it fits into bigger projects.

Neuroscience: ‘I can read your mind’

Rose Eveleth | 18 July 2014

(Getty Images)

What are you looking at? Scientist Jack Gallant can find out by decoding your thoughts, as Rose Eveleth discovers.

After leaders of the billion-euro Human Brain Project hit back at critics, six top neuroscientists have expressed "dismay" at their public response

Jack Gallant can read your mind. Or at least, he can figure out what you’re seeing if you’re in his machine watching a movie he’s playing for you.

Gallant, a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, has a brain decoding machine – a device that uses brain scanning to peer into people’s minds and reconstruct what they’re seeing. If mind-reading technology like this becomes more common, should we be concerned? Ask Gallant this question, and he gives a rather unexpected answer.

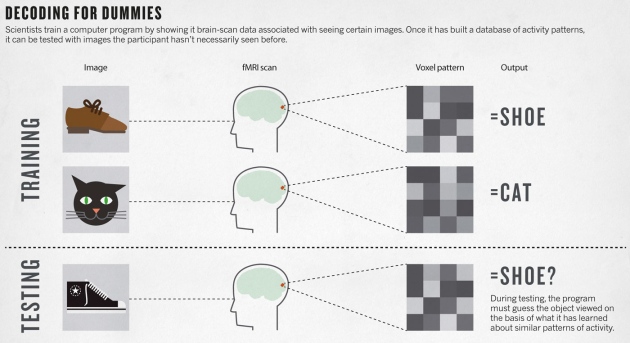

In Gallant’s experiment, people were shown movies while the team measured their brain patterns. An algorithm then used those signals to reconstruct a fuzzy, composite image, drawing on a massive database of YouTube videos. In other words, they took brain activity and turned it into pictures, revealing what a person was seeing.

For Gallant and his lab, this was just another demonstration of their technology. While his device has made plenty of headlines, he never actually set out to build a brain decoder. “It was one of the coolest things we ever did,” he says, “but it’s not science.” Gallant’s research focuses on figuring out how the visual system works, creating models of how the brain processes visual information. The brain reader was a side project, a coincidental offshoot of his actual scientific research. “It just so happens that if you build a really good model of the brain, then that turns out to be the best possible decoder.”

Science or not, the machine strokes the dystopian futurists among people who fear that the government could one day tap into our innermost thoughts. This might seem like a silly fear, but Gallant says it’s not. “I actually agree that you should be afraid,” he says, “but you don’t have to be afraid for another 50 years.” It will take that long to solve two of the big challenges in brain-reading technology: the portability, and the strength of the signal.

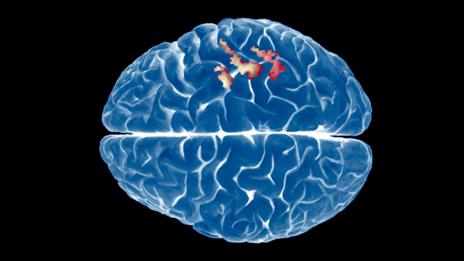

Decoding brain signals from scans can reveal what somebody is looking at (SPL)

Right now, in order for Gallant to read your thoughts, you have to slide into a functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine – a huge, expensive device that measures where the blood is flowing in the brain. While MRI is one of the best ways to measure the activity of the brain, it’s not perfect, nor is it portable. Subjects in an MRI machine can’t move, and the devices are expensive and huge.

And while comparing the brain image and the movie image side by side makes their connection apparent, the image that Gallant’s algorithm can build from brain signals isn’t quite like peering into a window. The resolution on MRI scans simply isn’t high enough to create something that generates a clear picture. “Until somebody comes up with a method for measuring brain activity better than we can today there won’t be many portable brain-decoding devices that will be built for a general use,” he says.

Dream reader

While Gallant isn’t working on trying to build any more decoding machines, others are. One team in Japan is currently trying to make a dream reader, using the same fMRI technique. But unlike in the movie experiment, where researchers know what the person is seeing and can confirm that image in the brain readouts, dreams are far trickier.

To try and train the system, researchers put subjects in an MRI machine and let them slip into that weird state between wakefulness and dreaming. They then woke up the subject and ask what they had seen. Using that information, they could correlate the reported dream images—everything from ice picks to keys to statues – to train the algorithm.

Using this database, the Japanese team was able to identify around 60% of the types of images dreamers saw. But there’s a key hurdle between these experiments and a universal dream decoder: each dreamer’s signals are different. Right now, the decoder has to be trained to each individual. So even if you were willing to sleep in an MRI machine, there’s no universal decoder that can reveal your nightly adventures.

Even though he’s not working on one, Gallant knows what kind of brain decoder he might build, should he chose to. “My personal opinion is that if you wanted to build the best one, you would decode covert internal speech. If you could build something that takes internal speech and translates into external speech,” he says, “then you could use it to control a car. It could be a universal translator.”

Inner speech

Some groups are edging closer to this goal; a team in the Netherlands, for instance, scanned the brains of bilingual speakers to detect the concepts each participant were forming – such as the idea of a horse or cow, correctly identifying the meaning whether the subjects were thinking in English or Dutch. Like the dream decoder, however, the system needed to be trained on each individual, so it is a far cry from a universal translator.

If nothing else, the brain reader has sparked more widespread interest in Gallant’s work. “If I go up to someone on the street and tell them how their brains work their eyes glaze over,” he says. When he shows them a video of their brains actually at work, they start to pay attention.

If you would like to comment on this, or anything else you have seen on Future, head over to our Facebook or Google+ page, or message us on Twitter.