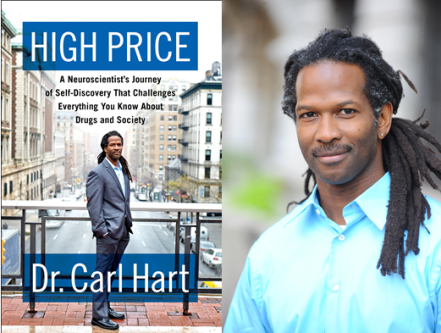

Carl Hart grew up in a rough neighborhood in Miami, selling drugs, doing petty crime, and carrying a gun. But he pulled himself out of the "hood" and became a neuroscientist and now teaches psychology and psychiatry at Columbia University.

He is the author of High Price: A Neuroscientist's Journey of Self-Discovery That Challenges Everything You Know About Drugs and Society (2013).

Neuroscientist Carl Hart: Everything You Think You Know About Drugs and Addiction Is Wrong

"The overwhelming majority of drug users don’t have a drug problem.”

September 17, 2014 | By April M. Short

Carl Hart grew up in Miami in what he calls the 'hood, a poor community with high rates of crime and prevalent drug use. He kept a gun in his car, engaged in petty crime and sold drugs. Today Hart is a neuroscientist and associate professor of psychology and psychiatry at Columbia University. He's also an expert on drug addiction. In a TEDMED Talk earlier this month, Hart explained how he went from dealing drugs in the 'hood to studying addiction at one of the world’s top universities. His talk summarizes some of the major themes from his book, High Price: A Neuroscientist's Journey of Self-Discovery That Challenges Everything You Know About Drugs and Society (2013).

Hart said growing up as he did, he came to believe the prevailing assertion that crack cocaine and other drugs were the villains behind crime and poverty. If he could only solve the addiction problem, he thought, he'd be tackling the root of the problem. As Hart came to learn, that is not the reality. Poverty and crime were around long before crack and other drugs appeared on the scene, and the forces at play that keep poor communities poor are insidious and systemic.

“My family, we were poor before drugs entered the picture,” Hart said. “I engaged in petty crime but it had nothing to do with drug addiction. It was about money and status. If you take drugs out of the equation, poverty and crime still exist. It’s not drug addiction causing people to commit crime. It’s other factors.”

One of the biggest factors is the war on drugs and its racist law enforcment policies, which target impoverished, black populations despite the fact that whites and blacks use drugs at similar rates.

“Drug laws are not uniformly enforced across all segments of our society, and this perpetuates the cycle of poverty and crime,” Hart said.

Hart said he first began questioning his thinking when he discovered that drugs like crack and meth are not nearly as addictive as he had been told. He points out in his talk that 80 to 90 percent of people who use illegal drugs are not addicted.

“The overwhelming majority of drug users don’t have a drug problem,” he said.

Hart’s work has revealed some striking truths about drug use and addiction. His research on both crack and meth users have shown that even drug users with serious addictions tend to make surprisingly rational decisions. When given the choice between drugs and money—even a small amount of money such as $5—they will choose the money over the drugs at least half the time. When the sum offered is higher, like $20 to $50, they will almost always choose the money.

As Hart told AlterNet last June, his studies have shown that the pharmacological effects of drugs rarely lead to crime, “but the public conflates these issues regardless.”

“Certainly, we have given thousands of doses of crack cocaine and methamphetamine to people in our lab, and never had any problems with violence or anything like that,” he said. “That tells you it's not the pharmacology of the drug, but some interaction with the environment or environmental conditions, that would probably happen without the drug.”

Hart said his TED Talk was an effort to educate the public about drug myths and bad US drug policy. “Millions of people languish unnecessarily in jails and prisons largely, and still others needlessly die from preventable overdoses, underground market violence and police interactions, due to a misguided approach to drug regulations,” he said. “And no one suffers more than African American men and the poor.”

Watch Hart’s talk below:

April M. Short is an associate editor at AlterNet. Follow her on Twitter @AprilMShort.