These powerful stories shatter preconceived notions about mental illness, and pose the provocative question: What can the world learn from different kinds of minds?

Playlist (9 talks)

14:52 - Elyn Saks A tale of mental illness -- from the inside

"Is it okay if I totally trash your office?" It's a question Elyn Saks once asked her doctor, and it wasn't a joke. A legal scholar, in 2007 Saks came forward with her own story of schizophrenia, controlled by drugs and therapy but ever-present. In this powerful talk, she asks us to see people with mental illness clearly, honestly and compassionately.

19:43 - Temple Grandin The world needs all kinds of minds

Temple Grandin, diagnosed with autism as a child, talks about how her mind works — sharing her ability to "think in pictures," which helps her solve problems that neurotypical brains might miss. She makes the case that the world needs people on the autism spectrum: visual thinkers, pattern thinkers, verbal thinkers, and all kinds of smart geeky kids.

14:17 - Eleanor Longden The voices in my head

To all appearances, Eleanor Longden was just like every other student, heading to college full of promise and without a care in the world. That was until the voices in her head started talking. Initially innocuous, these internal narrators became increasingly antagonistic and dictatorial, turning her life into a living nightmare. Diagnosed with schizophrenia, hospitalized, drugged, Longden was discarded by a system that didn't know how to help her. Longden tells the moving tale of her years-long journey back to mental health, and makes the case that it was through learning to listen to her voices that she was able to survive.

8:44 - Ruby Wax What's so funny about mental illness?

Diseases of the body garner sympathy, says comedian Ruby Wax — except those of the brain. Why is that? With dazzling energy and humor, Wax, diagnosed a decade ago with clinical depression, urges us to put an end to the stigma of mental illness.

22:18 - Sherwin Nuland How electroshock therapy changed me

Surgeon and author Sherwin Nuland discusses the development of electroshock therapy as a cure for severe, life-threatening depression — including his own. It’s a moving and heartfelt talk about relief, redemption and second chances.

5:51 - Joshua Walters On being just crazy enough

At TED's Full Spectrum Auditions, comedian Joshua Walters, who's bipolar, walks the line between mental illness and mental "skillness." In this funny, thought-provoking talk, he asks: What's the right balance between medicating craziness away and riding the manic edge of creativity and drive?

18:01 - Jon Ronson Strange answers to the psychopath test

Is there a definitive line that divides crazy from sane? With a hair-raising delivery, Jon Ronson, author of The Psychopath Test, illuminates the gray areas between the two. (With live-mixed sound by Julian Treasure and animation by Evan Grant.)

18:48 - Oliver Sacks What hallucination reveals about our minds

Neurologist and author Oliver Sacks brings our attention to Charles Bonnet syndrome — when visually impaired people experience lucid hallucinations. He describes the experiences of his patients in heartwarming detail and walks us through the biology of this under-reported phenomenon.

9:26 - Robert Gupta Music is medicine, music is sanity

Robert Gupta, violinist with the LA Philharmonic, talks about a violin lesson he once gave to a brilliant, schizophrenic musician — and what he learned. Called back onstage later, Gupta plays his own transcription of the prelude from Bach's Cello Suite No. 1.

Offering multiple perspectives from many fields of human inquiry that may move all of us toward a more integrated understanding of who we are as conscious beings.

Showing posts with label autism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label autism. Show all posts

Tuesday, November 11, 2014

TED Talk Playlist: All Kinds of Minds (9 Talks)

This is a cool collection of TED Talks entitled, "All kinds of minds." These nine talks "shatter" common beliefs and stereotypes about mental illness, or more accurately, neurodiversity.

Thursday, August 21, 2014

Excess Brain Synapses Associated with Autism (again) - There's a Drug for That . . . .

As soon as I read the title of this press release, my brain exploded with a booming, "NOOOOOOOOOO!!!!"

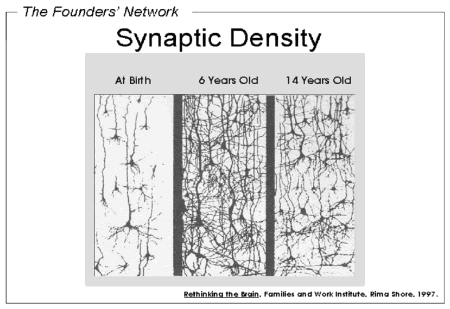

Another study has shown what many of us have long believed to be the source of autism - too many brain synapses that do not get pruned during the first 18 months of life (when the majority of pruning occurs, although there is another period of pruning in adolescence). This explanation makes sense with the old thinking about autism, which suggested that children withdraw, get violent, or tantrum when confronted with interpersonal stimuli and other environmental stimuli because it is overwhelming them. Having too many synapses would explain why it is overwhelming.

But these researchers were not content to know what autism is, they wanted to find the magic pill that would make it all better. What pill can do that, you might ask? Rapamycin, also known as a macrolide produced by the bacteria Streptomyces hygroscopicus. Essentially, it is used to prevent rejection in organ transplants - because it shuts down whole segments of the immune system (T cells and B cells).

What could possibly go wrong? Well, lung toxicity, cancer, and diabetes for starters.

Here is a little explanation of why this is a REALLY BAD idea.

The administration of rapamycin or any similar drug to the brains of infants/toddlers would have indiscriminate effects on the brain - total synapse volume might be reduced, but which synapses will be destroyed, and how would the overall experience of the child be impacted by this?

In normal development, synaptic pruning occurs in response to the child's environment, and one of the most important factors in determining synaptic pruning is the relational environment with the primary caregiver(s).

Here is a little more explanation on this from the book I am currently working on:

Synaptic pruning occurs in the first eighteen months of an infant’s development. Schore (1997) describes the neurobiology of how this restructuring of the brain occurs:[Emphasis added.]

Although the critical period of overproduction of synapses is genetically driven, the pruning and maintenance of synaptic connections [are] environmentally driven. This clearly implies that the developmental overpruning of a corticolimbic system that contains a genetically encoded underproduction of synapses represents a scenario for high risk conditions. (p. 618)“Developmental overpruning” refers to how the release of stress hormones leads to substantial neuronal death as a result of the toxicity of intense stress on the developing brain. Neurons in the important pathways linking the neocortex and limbic system—brain areas that handle emotional regulation—are most affected (Schore, 1996). According to Siegel (2012),

Children who may have a “genetically encoded underproduction of synapses,” or who may have a genetic variant that dysregulates the production of related neurotransmitters such as dopamine, may be at especially high risk if exposed to overwhelming stress. (p. 113)

There are "tens of thousands of new synapses being formed daily during the early years"of a child's development (Sullivan, 2012). At the same time, unused synapses are pruned away. The ones that are lost and the ones that remain are dependent on the experience of the child - the process is context specific, not random. And if it can be addressed without invasive drugs, for example, by learning and experience (both of which are ways the brain creates and releases connections), then why not try this avenue?

From the material above, it is clear that too few synapses also causes development issues, including depression, anxiety, conduct disorder, and lack of impulse control. It's a fine line between too many and too few synapses, and administration of a drug such as rapamycin not only results in random pruning, but may also create too much pruning.

Here is a longer passage from Sullivan on "experience-dependent plasticity":

Experience can determine the selective survival of neurons, the relative complexity of the axonal and dendritic branching, and the number of synapses that exist between cells.While the selection process in synaptic pruning is environmentally (and especially relationally) determined, the impetus of the pruning process is a genetic trigger. In autism, the genetic trigger either is not present or malfunctions. If there is to be ANY kind of intervention, it needs to target the genetic level, and quite possibly the molecular level of gene activity. It certainly should not target the developing brain.

Much of this experience-dependent control of brain development relies upon the experiences either increasing or decreasing the neural activity of a cell. For example, unused neurons (neurons with little neural activity) will die, while used neurons will survive. This is a normal process that occurs in the developing brain—too many cells are born and are then pruned. While new neurons are born in the brain throughout life, the enormity of early life growth is never replicated in later life. The implications of this process for custodial decisions in very early life are enormous—early life deprivation fails to activate neurons, which means that a greater number of neurons will die. Equally important, neurons that would typically die under “normal” conditions could be retained under deprivation or conditions of abuse. In either situation, brain function for the typical social environment in our Western culture might be compromised.

Okay, I now step down from my soapbox. Following the references cited above, here is the press release that got me all bent out of shape in the first place.

References (in order presented):

- Schore, AN. (1997). Early organization of the nonlinear right brain and development of a predisposition to psychiatric disorders. Development and Psychopathology: 9(4): 595–631.

- Schore, AN. (1996). The experience-dependent maturation of a regulatory system in the orbital prefrontal cortex and the origin of developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology; 8(1), 59–87.

- Siegel, DJ. (2012). The Developing Mind, Second Edition: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are; 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Sullivan, RM. (2012, Aug). The Neurobiology of Attachment to Nurturing and Abusive Caregivers. Hastings Law J.; 63(6): 1553–1570.

* * * * *

Here is the press release - the whole article is also freely available online.

Children with autism have extra synapses in brain: May be possible to prune synapses with drug after diagnosis

Date: August 21, 2014

Source: Columbia University Medical Center

Summary:

Children and adolescents with autism have a surplus of synapses in the brain, and this excess is due to a slowdown in a normal brain “pruning” process during development, according to a new study. Because synapses are the points where neurons connect and communicate with each other, the excessive synapses may have profound effects on how the brain functions.

In a study of brains from children with autism, researchers found that autistic brains did not undergo normal pruning during childhood and adolescence. The images show representative neurons from autistic (left) and control (right) brains; the spines on the neurons indicate the location of synapses. Credit: Guomei Tang, PhD and Mark S. Sonders, PhD/Columbia University Medical Center

Children and adolescents with autism have a surplus of synapses in the brain, and this excess is due to a slowdown in a normal brain "pruning" process during development, according to a study by neuroscientists at Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC). Because synapses are the points where neurons connect and communicate with each other, the excessive synapses may have profound effects on how the brain functions. The study was published in the August 21 online issue of the journal Neuron.

A drug that restores normal synaptic pruning can improve autistic-like behaviors in mice, the researchers found, even when the drug is given after the behaviors have appeared.

"This is an important finding that could lead to a novel and much-needed therapeutic strategy for autism," said Jeffrey Lieberman, MD, Lawrence C. Kolb Professor and Chair of Psychiatry at CUMC and director of New York State Psychiatric Institute, who was not involved in the study.

Although the drug, rapamycin, has side effects that may preclude its use in people with autism, "the fact that we can see changes in behavior suggests that autism may still be treatable after a child is diagnosed, if we can find a better drug," said the study's senior investigator, David Sulzer, PhD, professor of neurobiology in the Departments of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Pharmacology at CUMC.

During normal brain development, a burst of synapse formation occurs in infancy, particularly in the cortex, a region involved in autistic behaviors; pruning eliminates about half of these cortical synapses by late adolescence. Synapses are known to be affected by many genes linked to autism, and some researchers have hypothesized that people with autism may have more synapses.

To test this hypothesis, co-author Guomei Tang, PhD, assistant professor of neurology at CUMC, examined brains from children with autism who had died from other causes. Thirteen brains came from children ages two to 9, and thirteen brains came from children ages 13 to 20. Twenty-two brains from children without autism were also examined for comparison.

Dr. Tang measured synapse density in a small section of tissue in each brain by counting the number of tiny spines that branch from these cortical neurons; each spine connects with another neuron via a synapse.

By late childhood, she found, spine density had dropped by about half in the control brains, but by only 16 percent in the brains from autism patients.

"It's the first time that anyone has looked for, and seen, a lack of pruning during development of children with autism," Dr. Sulzer said, "although lower numbers of synapses in some brain areas have been detected in brains from older patients and in mice with autistic-like behaviors."

Clues to what caused the pruning defect were also found in the patients' brains; the autistic children's brain cells were filled with old and damaged parts and were very deficient in a degradation pathway known as "autophagy." Cells use autophagy (a term from the Greek for self-eating) to degrade their own components.

Using mouse models of autism, the researchers traced the pruning defect to a protein called mTOR. When mTOR is overactive, they found, brain cells lose much of their "self-eating" ability. And without this ability, the brains of the mice were pruned poorly and contained excess synapses. "While people usually think of learning as requiring formation of new synapses, "Dr. Sulzer says, "the removal of inappropriate synapses may be just as important."

The researchers could restore normal autophagy and synaptic pruning -- and reverse autistic-like behaviors in the mice -- by administering rapamycin, a drug that inhibits mTOR. The drug was effective even when administered to the mice after they developed the behaviors, suggesting that such an approach may be used to treat patients even after the disorder has been diagnosed.

Because large amounts of overactive mTOR were also found in almost all of the brains of the autism patients, the same processes may occur in children with autism.

"What's remarkable about the findings," said Dr. Sulzer, "is that hundreds of genes have been linked to autism, but almost all of our human subjects had overactive mTOR and decreased autophagy, and all appear to have a lack of normal synaptic pruning. This says that many, perhaps the majority, of genes may converge onto this mTOR/autophagy pathway, the same way that many tributaries all lead into the Mississippi River. Overactive mTOR and reduced autophagy, by blocking normal synaptic pruning that may underlie learning appropriate behavior, may be a unifying feature of autism."

Alan Packer, PhD, senior scientist at the Simons Foundation, which funded the research, said the study is an important step forward in understanding what's happening in the brains of people with autism.

"The current view is that autism is heterogeneous, with potentially hundreds of genes that can contribute. That's a very wide spectrum, so the goal now is to understand how those hundreds of genes cluster together into a smaller number of pathways; that will give us better clues to potential treatments," he said.

"The mTOR pathway certainly looks like one of these pathways. It is possible that screening for mTOR and autophagic activity will provide a means to diagnose some features of autism, and normalizing these pathways might help to treat synaptic dysfunction and treat the disease."

The paper is titled, "Loss of mTOR-dependent macroautophagy causes autistic-like synaptic pruning deficits." Other authors are: Kathryn Gudsnuk, Sheng-Han Kuo, Marisa L. Cotrina, Gorazd Rosoklija, Alexander Sosunov, Mark S. Sonders, Ellen Kanter, Candace Castagna, Ai Yamamoto, Ottavio Arancio, Bradley S. Peterson, Frances Champagne, Andrew J. Dwork, and James Goldman from CUMC; and Zhenyu Yue (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai). Marisa Cotrina is now at the University of Rochester.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by Columbia University Medical Center. Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.

Journal Reference:

Tang, G, Gudsnuk, K, Kuo, SH, Cotrina, ML, Rosoklija, G, Sosunov, A, Sonders, MS, et al. (2014). Loss of mTOR-Dependent Macroautophagy Causes Autistic-like Synaptic Pruning Deficits. Neuron; Epub ahead of print. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.040

Monday, August 11, 2014

M. J. Friedrich - Research on Psychiatric Disorders Targets Inflammation

This is an interesting overview of the current research on how inflammation can play a role in depression, schizophrenia, and autism. I suspect there is much more research to be done in this realm, but I believe they need to stop using pharmacological interventions targeted at a specific molecule or hormone in the immune response (such as the tumor necrosis factor [TNF] antagonist infliximab, which only showed limited efficacy in treatment resistant depression, and then only for those who had high levels of inflammation before the trial).

Rather, the use of a general anti-inflammatory agent, such as curcumin or omega-3 fats, among many others, might offer greater benefits in that they target several different immune system products. Further, improving the health of the microbiome can be the most effective method to reduce inflammation, which is as simple as a healthy diet.

Full Citation:

Friedrich, MJ. (2014, Aug 6). Research on Psychiatric Disorders Targets Inflammation. JAMA; 312(5): 474-476. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.8276.

Research on Psychiatric Disorders Targets Inflammation

M. J. Friedrich

New York—Activation of the immune system is the body’s natural reaction to infection or tissue damage, but when this protective response is prolonged or excessive, it can play a role in many chronic illnesses, not only of the body, but also of the brain.

“Psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders are being thought of more and more as systemic illnesses in which inflammation is involved,” noted Eric Hollander, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York City. The cause of increased inflammation in these conditions isn’t always clear, but it has become a hot topic of investigation.

Hollander, who spoke at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association held here in May, was among several investigators who discussed how immune-inflammatory mechanisms can go awry and contribute to the development of depression, schizophrenia, and autism, insights that are leading to novel experimental approaches for these and other disorders.

CYTOKINES IN DEPRESSION

“The notion that inflammation plays a role in neuropsychiatric disorders really caught fire in the context of depression,” said Andrew Miller, MD, of Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta.

This idea came from early studies showing that patients with depression, regardless of their physical health status, exhibited cardinal features of inflammation, including increases in inflammatory cytokines in the blood and cerebral spinal fluid. The inflammatory cytokines interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), as well as the acute-phase reactant c-reactive protein (CRP), are the most reliable biomarkers of increased inflammation in patients with depression, said Miller.

Studies suggest that proinflammatory processes may be activated in people with autism spectrum disorders. A medicalized parasite, the eggs of porcine whipworms, tamps down the body’s proinflammatory response and is being studied as a possible treatment for reducing symptoms of autism. CNRI/www.sciencesource.com

Interestingly, there seems to be a special relationship between inflammation and treatment-resistant depression (TRD), which occurs in about one-third of all depressed patients, said Miller. Patients who don’t respond to antidepressant therapy tend to show an increase in inflammatory markers. Data indicate that these inflammatory molecules can sabotage and circumvent the mechanisms of action of conventional antidepressant therapy.

Given the association of inflammatory cytokines with TRD, researchers set out to test the therapeutic potential of inhibiting inflammatory cytokines in this subset of patients. Administration of a TNF antagonist has been shown to improve depressed mood in patients with other disorders, such as psoriasis and Crohn disease, suggesting that this approach might help reverse depressive symptoms in otherwise healthy patients with TRD.

In a recent proof-of-concept study, Miller and his colleagues gave infusions of the monoclonal antibody infliximab, a TNF antagonist, to 60 adults with major depression that was at least moderately resistant to medication (Raison CL et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70[1]:31-41). Based on the hypothesis that an anticytokine strategy might be effective only in patients with high inflammation before treatment, the researchers also measured CRP and other inflammatory biomarkers at baseline and throughout the study.

Infliximab did not prove to be more effective than placebo in treating TRD in the study. In fact, overall, those treated with placebo did better than those who received infliximab, said Miller. However, when patients were stratified on the basis of inflammatory biomarkers, those patients with high baseline measurements (plasma CRP concentrations >5 mg/L) had the best response to infliximab.

These results indicate that a simple test for a peripheral blood biomarker of inflammation like CRP might predict which patients would respond to immune-targeted therapy for depression, said Miller. “It’s one of the first studies in psychiatry connecting a biomarker to treatment response,” he noted.

In a subsequent study, Miller’s team compared gene expression profiles of the participants who responded to infliximab with those who did not respond. Within 6 hours after the first infusion of infliximab, the researchers were able to distinguish responders from nonresponders (Mehta D et al. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;31:205-215).

Miller’s group has also been working to identify the brain regions and pathways that are targeted by inflammatory cytokines, such as interferon-alpha—work that may lead to more personalized treatment options for patients with depression, he said (Capuron L et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69[10]:1044-1053).

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY TREATMENT IN SCHIZOPHRENIA

A role for the inflammatory process is also being explored in schizophrenia, noted Norbert Müller, MD, PhD, of Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Germany.

The influence of infectious agents on the pathogenesis of schizophrenia, as well as on other psychiatric disorders, has been discussed for decades, and prenatal and postnatal infections are considered risk factors for schizophrenia. Research in prenatal infections indicates that the culprit is not a specific infectious agent, but rather the maternal immune response (Krause D et al. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11[5]:739-743).

Data from a 30-year population-based register study indicate that inflammation coming from either infection or autoimmunity is a risk factor for schizophrenia, not only during development but also later in life (Benros ME et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2011; 168[12]: 1303-1310). The risk seems to increase in a dose-dependent manner, with the risk increasing along with the number of infections, for example, said Müller.

Because of the apparent involvement of inflammatory processes in schizophrenia, the use of anti-inflammatory compounds for the disorder has received increasing attention. A number of studies carried out in the past decade using cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors in addition to antipsychotic medication have shown a therapeutic effect for the disorder.

Müller noted that timing seems to influence response to this anti-inflammatory therapy because no benefit was seen in a study involving patients who had a long duration of disease (Rapaport MH et al. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1594-1596). Rather, the most compelling data was for anti-inflammatory therapies carried out in the early phase of the disorder: a recent meta-analysis showed an advantage of COX-2 inhibitors only among patients who had a short duration of the disorder (Nitta M et al. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39[6]:1230-1241).

“From an immunologic point of view, this fits very well,” said Müller. “If you have chronic inflammation, it’s more or less impossible to treat effectively with a short-term anti-inflammatory therapy,” he said.

Müller’s group is also beginning to use interferon γ to activate the cellular arm of immunity (type 1 response), which appears to be blunted in most patients with schizophrenia. The work is only in early stages but so far has shown some promise.

INFLAMMATORY MECHANISMS IN AUTISM

A hyperactive immune system is also postulated to play a role in people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Increases in proinflammatory cytokines have been found both in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with ASD and in postmortem brain tissue from deceased patients with autism, said Montefiore’s Hollander.

The association between immune dysfunction and ASD has led researchers to test several novel treatments that target inflammatory mechanisms to alleviate some symptoms of ASD.

One of these mechanisms involves the gut microbiome. “We can think about certain bacteria and parasites in the gut as helping to dampen the chronic inflammatory response, and that a lack of favorable gut parasites allows proinflammatory cytokines to prevail,” said Hollander.

When the microbiome is deprived, as the “hygiene hypothesis” contends has happened in developed countries, it may lead to a lack of control of the immune system. This could help explain why developed countries have higher rates of autoimmune conditions, although other factors—such as underdiagnosis—could also contribute to the lower rates in low- and middle-income countries.

Hollander and his colleagues have focused on trying to beef up the microbiome in people with ASD by introducing a medicalized parasite, Trichuris suis ova (TSO), the eggs of a porcine whipworm. Trichuris suis ova is safe in humans, does not multiply in the host, is not transmittable by contact, and is cleared from the system spontaneously.

Trichuris suis ova works by tamping down the proinflammatory response to increase its survival within the host. It has been studied with some success in autoimmune diseases such as Crohn disease and inflammatory bowel disease and appears to achieve its effects by shifting the balance of T-regulator and T-helper cells and their respective cytokines, said Hollander.

Hollander’s group has been carrying out a small preliminary study of TSO in 10 high-functioning adults with ASD who were able to give informed consent. All participants had a family or personal history of some kind of a seasonal or food allergy or a family history of autoimmune problems.

The aim of identifying this subset of people with ASD was to stratify the study population according to signs of immune dysfunction. In this way, researchers can study a more homogeneous group of people within what is considered a very heterogeneous illness, said Hollander.

In a 28-week, double-blind, randomized, crossover study, the patients received TSO for 3 months (2500 eggs every 2 weeks) followed 4 weeks later by placebo treatment for 3 months. After the first 12-week phase of TSO or placebo, the patients entered a 4-week washout before beginning the second 12-week phase.

The researchers used several measurements to assess symptoms, including stereotypy (self-stimulatory behavior), repetitive behavior, and rigidity or craving for sameness. In their interim analysis of this pilot study, they demonstrated the feasibility and safety of using TSO in an adult population with autism and have found a potential benefit from treatment in all these domains.

Hollander’s team is in the process of launching a new study of this same approach in a pediatric population with ASD, based on the idea that early intervention in developmental disorders is optimal.

In a different therapeutic approach, Hollander and his colleagues studied 10 children with ASD who had a history of symptom improvement when they had fevers. All the children spent alternate days soaking in a hot tub at 102°F (to mimic fever) or at 98°F (control condition).

The children showed improvements on the days when their body temperature was raised to 102°F, compared with the days they were bathed at 98°F. Benefits were seen particularly in restricted and repetitive behavior as well as social behavior, said Hollander.

The mechanism of action is under investigation, but researchers conjecture that raising the body’s temperature either through fever or a hot tub bath releases anti-inflammatory signals that can bring about the observed behavioral effects.

Future studies need to be done to replicate many of these findings. But researchers suggest the data represent a step toward personalizing therapies for psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders and provide promise for the development of inflammatory biomarkers and treatment approaches for patients who are responsive to immune-targeted therapies.

Tuesday, January 28, 2014

Dr. Temple Grandin: Authors At Google

Dr. Temple Grandin comes to Google to talk about her book: The Autistic Brain: Thinking Across the Spectrum.

Dr. Temple Grandin: Authors At Google

Published on Jan 18, 2014

When Temple Grandin was born in 1947, autism had only just been named. Today it is more prevalent than ever, with one in 88 children diagnosed on the spectrum. And our thinking about it has undergone a transformation in her lifetime: Autism studies have moved from the realm of psychology to neurology and genetics, and there is far more hope today than ever before thanks to groundbreaking new research into causes and treatments. Now Temple Grandin reports from the forefront of autism science, bringing her singular perspective to a thrilling journey into the heart of the autism revolution.

Weaving her own experience with remarkable new discoveries, Grandin introduces the neuroimaging advances and genetic research that link brain science to behavior, even sharing her own brain scan to show us which anomalies might explain common symptoms. We meet the scientists and self-advocates who are exploring innovative theories of what causes autism and how we can diagnose and best treat it. Grandin also highlights long-ignored sensory problems and the transformative effects we can have by treating autism symptom by symptom, rather than with an umbrella diagnosis. Most exciting, she argues that raising and educating kids on the spectrum isn't just a matter of focusing on their weaknesses; in the science that reveals their long-overlooked strengths she shows us new ways to foster their unique contributions.

From the "aspies" in Silicon Valley to the five-year-old without language, Grandin understands the true meaning of the word spectrum. The Autistic Brain is essential reading from the most respected and beloved voices in the field.

Monday, August 19, 2013

The Horse Boy - Autism, Horses, and Mongolian Shamans

When Rupert Isaacson and Kristin Neff (parents of Rowan) reach their limit in caring for their autistic son, having tried medications, diets, and everything else, they seek a more traditional method of healing - horses and shamans.

They journey to Mongolia with Rowan and seek out various shamans for healing, eventually making their way to the Reindeer People (who ride reindeer), where the possibility of a miracle healing is presented to them.

With commentary along the way from Dr. Temple Grandin and Dr. Simon Baron-Cohen, among others, we also learn what it means to have autism and to be non-neurotypical.

How far would you travel to heal someone you love? An intensely personal yet epic spiritual journey, THE HORSE BOY follows one Texas couple and their autistic son as they trek on horseback through Outer Mongolia, in a desperate attempt to treat his condition with shamanic healing.

A complex condition that can dramatically affect social interaction and communication skills, autism is the fastest-growing developmental disability today. After two-year-old Rowan Isaacson was diagnosed with autism, he ceased speaking, retreated into himself for hours at a time, and often screamed inconsolably for no apparent reason. Rupert Isaacson, a writer and former horse trainer, and his wife Kristin Neff, a psychology professor, sought the best possible medical care for their son. But traditional therapies had little effect.

Then they discovered that Rowan has a profound affinity for animals, particularly horses. When Rupert began to ride with Rowan every day, Rowan began to talk again and engage with the outside world. Was there a place on the planet that combined horses and healing? There was — Mongolia, the country where the horse was first domesticated, and where shamanism is the state religion. What if we were to take Rowan there, thought Rupert, and ride on horseback from shaman to shaman? What would happen?

THE HORSE BOY is a magical expedition from the wild open steppe to the sacred Lake Sharga. As the family sets off on a quest for a possible cure, Rupert and Kristin find their son is accepted — even treasured — for his differences. By telling one family’s extraordinary story, the film gives a voice to the thousands of families who are living with autism every day. As Rupert and Kristin struggle to make sense of their child’s autism, and find healing for him and themselves in this unlikeliest of places, Rowan makes dramatic leaps forward, astonishing both his parents and himself.

Wednesday, May 22, 2013

Cindy Wigglesworth - Good Human Beings and the Right Temporoparietal Junction

From Huffington Post's TED Weekends, this article by Cindy Wigglesworth (author of SQ 21: The Twenty-One Skills of Spiritual Intelligence) in response to Rebecca Saxe's TED Talk, How We Read Each Other's Minds.

Other authors also responded to this TED Talk:

Other authors also responded to this TED Talk:

- Derek Flood - The Complexity of Humans

- Hannah Brown - Autism, Empathy And The Sally-Anne Test

- Barbara Ficarra - Equipped For Empathy?

- Phillip M. Miner - The Neurology Of Disgust

- Jonathan Appel - Brain To Brain: Turning Neuroscience Into Wisdom

Good Human Beings and the Right Temporoparietal Junction

Cindy Wigglesworth

Posted: 05/18/2013

Click here to read an original op-ed from the TED speaker who inspired this post and watch the TEDTalk below.When we watch a short video like Rebecca Saxe's TEDTalk we may be left confused. What does this mean for us in terms of morality?

In the April 2010 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the article by Rebecca Saxe and her co-authors make the context of their research around the RTPJ more clear: "According to a basic tenet of criminal law, 'the act does not make the person guilty unless the mind is also guilty.'" We can see why it would be good for a juror to have a well-developed RTPJ. We need to see the intention of the accused.

But is a well-developed RTPJ sufficient to create a moral or exemplary human being?

Let's consider who might represent our ideal moral human being. Who are the noblest people you know of? When I ask people this question similar names occur again and again. People like Nelson Mandela, the Buddha, Jesus, the Dalai Lama, Abraham Lincoln, Aung San Suu Kyi, Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Mother Teresa and other spiritual leaders, visionary leaders and political peace activists. I then ask what do you admire about these people? Typical replies include that they are: wise, compassionate, courageous, authentic, visionary, forgiving and humble.

I suggest we hold those characteristics as the crucial context -- the "true north" -- as we examine the innovations and discoveries of neuroscience. As a society we hopefully care deeply about how we can get a little closer to that level of goodness. We can hope that science can help us chart a path in this direction, or at least point out the roadblocks.

Most of us would agree that one strong example of a "not-good" person is the psychopath. Psychopathy is "a psychological condition in which the individual shows a profound lack of empathy for the feelings of others, a willingness to engage in immoral and antisocial behavior for short-term gains, and extreme egocentricity." [1] This "profound lack of empathy" means he only cares about what he wants and feels no guilt about manipulating or using aggression to get it. These folks scare us. And they teach us something important about the path to goodness: it must include empathy.

Empathy is frequently discussed as involving at least two types:cognitive empathy and emotional (or affective) empathy. Cognitive empathy involves thinking things through to see from the other person's point of view. It is sometimes called Theory of Mind. If we predict well we can accurately guess what the other person will do, assume or feel. In the pirates with the cheese sandwiches the older children could think from the point of view of the first pirate and see why he would assume that the sandwich on top of the chest was his sandwich. This is a useful skill. It enhances moral judgment because we can see that the first pirate made a reasonable assumption and had no evil intent. But cognitive empathy is only part of being a good human being. In fact, some psychopaths have good cognitive empathy.[2] It may help them accurately predict how others will react to their manipulations.

Emotional empathy is a much more visceral experience. It includes limbic system resonance where the emotions you are feeling trigger parallel physiological and emotional reactions in me.[3] I am "feeling with" you. Emotional empathy may create the "brake" on our tendency to act from self-interest in aggressive ways. If my aggression is going to hurt you, and your pain is felt in my body, I am likely to pause and perhaps stop or lessen my aggression.[4]

I would suggest that we need both cognitive empathy (requiring a well-developed RTPJ) and emotional empathy as part of being "non-psychopaths." But does that make us good people? Not quite. Something more is needed.

What sets a truly noble person apart? What makes a Gandhi, Dalai Lama, or Mother Teresa different? There is a decision made by these people to hold themselves to a higher standard. They make a decision to live up to noble values -- to live from their highest nature. In what part of the brain does this ability reside? To my knowledge no one has fully answered this yet. I suspect we will find that the executive decision-making center of the brain, residing in the prefrontal cortex, is involved. I believe our path to nobility will call upon the emotional and logical components of the brain. There will be also a piece of right brain visioning required. I believe there will be some developmental neural "weight-lifting" and whole-brain integration skills. We will have to conceptualize what nobility looks like and then integrate our whole brain to align with that goal. We will then have to make daily choices and take actions so we can live toward that ideal. All this, if true, will mean that the RTPJ will be just one piece in our nobility-machinery.

[1] Almost a Psychopath by Ronald Schouten, MD, JD and James Silver, JD, p.18 2012 Harvard University

[2] In addition to the hyperlink you might want to look at this article by R. James R. Baird, National Institute of Mental Health

[3] For more on this I recommend A General Theory of Love by Thomas Lewis, MD, Fari Amini, MD and Richard Lannon, MD, Random House, 2000.

[4] For more on this I recommend The Science of Evil: On Empathy and the Origins of Cruelty by Simon Baron-Cohen, Basic Books, 2012

My TEDTalk, above, is about the process by which we learn to read each other. Here are five reasons that I study how human brains think about other minds.

(1) It is a hard, and awesome, problem. To me, the most breathtaking idea I've ever heard is that each thought a person ever has, every moment of experience, of insight, of reflection, of aspiration, is equivalent to a pattern of brain cells firing in space and time. How does a pattern of brain activity constitute a moral judgment? A moment of empathy for a fictional character? The idea for a sentence you're about to write? Someday, scientists will be able to imagine, simultaneously, these abstract thoughts and how each corresponds to a specific pattern of brain activity. I don't expect this understanding to arrive in my lifetime. But it's thrilling to imagine that future, and to feel that my research might be a small step on the route that gets us there.

(2) It matters to society. Some of the hardest problems we face as humans are social problems: how to get a group of people to agree on a set of goals, and a path to achieving those goals, and in some cases a set of small individual compromises or sacrifices in the interest of the long term and the greater good. Fortunately, cooperating in large groups is a signature accomplishment of the human brain: among similar species, we are remarkably good at working together and negotiating our differences. On the other hand, there is still a long way to go, and a lot we don't know. Our current techniques for persuasion and coordination depend on our intuitions about how to inspire people to act. As an analogy, our human intuitions about physics are good enough to let us catch a baseball at 350 feet, but if NASA had used intuitive physics to get to the moon, the Eagle would have missed. I hope my research will be a step along the way toward a true theory of how people respond to other people, the theory that helps us to coordinate even more powerfully to get where we're going next.

(3) It might help treat disease. Many forms of developmental disorders and brain diseases disproportionately affect people's relationships with others. For example, some children with autism spectrum disorders are extremely intelligent, and can solve logical and mathematical problems that would stump other kids, but don't want to be hugged, don't like sharing experiences, don't respond to a smile. This disconnect can be devastating, especially for the children's caregivers. Another example is fronto-temporal dementia, a progressive brain disease somewhat like Alzheimer's, except that the first symptom is emotional callousness. Patients with this disease usually aren't aware of anything wrong at first; they come to the doctor at the insistence of their (often angry and deeply hurt) spouses. I hope that my research on the biology of social interaction might some day lead to better diagnosis, and better treatments, for these diseases.

(4) It keeps me busy. The problems I work on connect to so many other disciplines. The tools I use for taking images of people's brains depend on physics. The signal I measure depends on the biology of brain cell metabolism. The inferences I make from my data depend on neuroscience. My colleagues working on similar problems are developmental psychologists studying human children, comparative psychologists studying non-human primates, and social psychologists studying how people interact. I speak to audiences of philosophers, of economists, of lawyers and judges. Connecting to all of these different disciplines keeps me on my toes. There has never, in the 14 years I have worked on this topic, been a moment when I felt that I knew enough.

(5) Luck. In my first year in graduate school, I tried five experiments. Four failed. This research came from the one that worked.

Ideas are not set in stone. When exposed to thoughtful people, they morph and adapt into their most potent form. TEDWeekends will highlight some of today's most intriguing ideas and allow them to develop in real time through your voice! Tweet #TEDWeekends to share your perspective or emailtedweekends@huffingtonpost.com to learn about future weekend's ideas to contribute as a writer.

Monday, April 29, 2013

THE SOCIAL BRAIN on the All in the Mind Podcast

On this week's All in the Mind, Lynne Malcolm speaks with Uta Frith (Emeritus Professor of Cognitive Development, University of London; Research Foundation Professor, University of Aarhus) and Chris Frith (Emeritus Professor of Neuropsycholgy, University College London).

This episode looks at what autism, Aspergers syndrome, and other autism-spectrum disorders can tell us about the social brain.

This episode looks at what autism, Aspergers syndrome, and other autism-spectrum disorders can tell us about the social brain.

THE SOCIAL BRAIN

Listen now

Download audio

show transcript

Broadcast: Sunday 28 April 2013

For most people the ability to interact and communicate with each other seems almost second nature – but for those with a condition on the autism spectrum social skills can be difficult to grasp and challenging. We hear from the pioneering autism researcher from the U.K Uta Frith and neuroscientist Chris Frith about what autism and Aspergers Syndrome can teach us about our Social Brain.

Show Transcript

Guests:

- Uta Frith, Emeritus Professor of Cognitive Development, University of London. Research Foundation Professor, University of Aarhus

- Chris Frith, Emeritus Professor of Neuropsycholgy, University College London.

- Thomas Kuzma, Young adult with Aspergers Syndrome

- Benison O'Reilly, Author & mother of child with Autism

Publications

The Australian Autism Handbook. Benison O'Reilly and Kathryn Wicks. Jane Curry Publishing.

Further Information:Presenter: Lynne Malcolm

Thursday, April 25, 2013

Steve Silberman - Neurodiversity Rewires Conventional Thinking About Brains

Not all brains are created equal, which is a good thing. But based on the pharmaceutical industry's desire to have us all taking pills that homogenize us, you would never be able to tell that neurodiversity is an evolutionary advantage.

This article from Wired Magazine looks at the origins and popularization of neurodiversity.

This article from Wired Magazine looks at the origins and popularization of neurodiversity.

Neurodiversity Rewires Conventional Thinking About Brains

By Steve Silberman | April 16, 2013

ILLUSTRATION: MARK WEAVER

In the late 1990s, a sociologist named Judy Singer—who is on the autism spectrum herself—invented a new word to describe conditions like autism, dyslexia, and ADHD: neurodiversity. In a radical stroke, she hoped to shift the focus of discourse about atypical ways of thinking and learning away from the usual litany of deficits, disorders, and impairments. Echoing positive terms like biodiversity and cultural diversity, her neologism called attention to the fact that many atypical forms of brain wiring also convey unusual skills and aptitudes.

Autistic people, for instance, have prodigious memories for facts, are often highly intelligent in ways that don’t register on verbal IQ tests, and are capable of focusing for long periods on tasks that take advantage of their natural gift for detecting flaws in visual patterns. By autistic standards, the “normal” human brain is easily distractible, is obsessively social, and suffers from a deficit of attention to detail. “I was interested in the liberatory, activist aspects of it,” Singer explained to journalist Andrew Solomon in 2008, “to do for neurologically different people what feminism and gay rights had done for their constituencies.”

The new word first appeared in print in a 1998 Atlantic article about Wired magazine’s website, HotWired, by journalist Harvey Blume. “Neurodiversity may be every bit as crucial for the human race as biodiversity is for life in general,” he declared. “Who can say what form of wiring will prove best at any given moment? Cybernetics and computer culture, for example, may favor a somewhat autistic cast of mind.”

Thinking this way is no mere exercise in postmodern relativism. One reason that the vast majority of autistic adults are chronically unemployed or underemployed, consigned to make-work jobs like assembling keychains in sheltered workshops, is because HR departments are hesitant to hire workers who look, act, or communicate in non-neurotypical ways—say, by using a keyboard and text-to-speech software to express themselves, rather than by chattering around the water cooler.

One way to understand neurodiversity is to remember that just because a PC is not running Windows doesn’t mean that it’s broken. Not all the features of atypical human operating systems are bugs. We owe many of the wonders of modern life to innovators who were brilliant in non-neurotypical ways. Herman Hollerith, who helped launch the age of computing by inventing a machine to tabulate and sort punch cards, once leaped out of a school window to escape his spelling lessons because he was dyslexic. So were Carver Mead, the father of very large scale integrated circuits, and William Dreyer, who designed one of the first protein sequencers.

Singer’s subversive meme has also become the rallying cry of the first new civil rights movement to take off in the 21st century. Empowered by the Internet, autistic self-advocates, proud dyslexics, unapologetic Touretters, and others who think differently are raising the rainbow banner of neurodiversity to encourage society to appreciate and celebrate cognitive differences, while demanding reasonable accommodations in schools, housing, and the workplace.

A nonprofit group called the Autistic Self Advocacy Network is working with the US Department of Labor to develop better employment opportunities for all people on the spectrum, including those who rely on screen-based devices to communicate (and who doesn’t these days?). “Trying to make someone ‘normal’ isn’t always the best way to improve their life,” says ASAN cofounder Ari Ne’eman, the first openly autistic White House appointee.

Neurodiversity is also gaining traction in special education, where experts are learning that helping students make the most of their native strengths and special interests, rather than focusing on trying to correct their deficits or normalize their behavior, is a more effective method of educating young people with atypical minds so they can make meaningful contributions to society. “We don’t pathologize a calla lily by saying it has a ‘petal deficit disorder,’” writes Thomas Armstrong, author of a new book called Neurodiversity in the Classroom. “Similarly, we ought not to pathologize children who have different kinds of brains and different ways of thinking and learning.”

In forests and tide pools, the value of biological diversity is resilience: the ability to withstand shifting conditions and resist attacks from predators. In a world changing faster than ever, honoring and nurturing neurodiversity is civilization’s best chance to thrive in an uncertain future.

Sunday, April 07, 2013

Brainstorm - To The Best of Our Knowledge (NPR)

From this week's To The Best of Our Knowledge (on NPR), a collection of five segments/interviews on the human brain. Richard Davidson talks about his most recent book, The Emotional Life of Your Brain; David and Kristen Finch talk about his battle with Asperger's Syndrome, and the book he wrote about the process, The Journal of Best Practices: A Memoir of Marriage, Asperger Syndrome, and One Man's Quest to Be a Better Husband; Martha Herbert talks about autism and her book, The Autism Revolution: Whole-Body Strategies for Making Life All It Can Be; V.S. Ramachandran talks about "phantom limb syndrome" and his book, The Tell-Tale Brain: A Neuroscientist's Quest for What Makes Us Human; and Frank Browning talks about "the dancing brain."

This episode (or parts of it) originally aired in 2012.

This episode (or parts of it) originally aired in 2012.

Brainstorm

04.07.2013

(was 04.15.2012)

Listen

Download

Interviewer(s):

Guest(s):

We explore the frontiers of brain science, from the neurobiology of emotions to recent discoveries about autism. Renowned neuroscientists Richard Davidson and V.S. Ramachandran reveal new insights into the brain, and we'll hear the story of one marriage saved by a diagnosis of Asperger Syndrome.

Would you like to take the Aspie quiz? Here's a link:

RELATED LINK(S):

* * * * *

MARTHA HERBERT ON "THE AUTISM REVOLUTION"

Listen

Download

Extended Interview

Transcript

Autism's a tricky diagnosis. And its causes are also mysterious. Harvard Medical School neurologist Martha Herbert t advocates a whole-body approach, which looks at environmental toxins, vitamin deficiencies and immune problems.

* * * * *

DAVID AND KRISTEN FINCH ON ASPERGER DIAGNOSIS

Listen

Download

Transcript

The marriage of David and Kristen Finch was falling apart when Kristen asked Dave to take the "Aspie quiz." It turns out Dave has Asperger Syndrome. They talk about how the diagnosis changed their lives.

* * * * *

RICHARD DAVIDSON ON THE EMOTIONAL BRAIN

Listen

Download

Transcript

Neuroscientist Richie Davidson has developed an entirely new model for understanding the science of emotions. He talks about this paradigm shift and the personal journey that led to it.

* * * * *

FRANK BROWNING ON THE DANCING BRAIN

Listen

Download

Transcript

What happens in your brain when you dance? Frank Browning talks with scientists and choreographers in France and the U.S. about the "dancing brain."

* * * * *

V.S. RAMACHANDRAN ON PHANTOM LIMB SYNDROME

Listen

Download

Transcript

Neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran is renowned for his ability to crack strange neurological mysteries. He tells Steve Paulson about the science behind phantom limb syndrome and his ingenious treatment for it.

RELATED BOOKS:

The Autism Revolution: Whole-Body Strategies for Making Life All It Can Be

(Martha Dr Herbert, Karen Weintraub)

The Journal of Best Practices: A Memoir of Marriage, Asperger Syndrome, and One Man's Quest to Be a Better Husband

(David Finch)

Monday, December 17, 2012

Neuroscience and Morality on The Mind Report - Jonathan Phillips (Yale University) and Liane Young (Boston College)

This week's episode of The Mind Report (from BloggingHeads.tv) features Jonathan Phillips (Yale University) and Liane Young (Boston College) discussing the neuroscience of morality and the mind.

THE MIND REPORT

THE MIND REPORT

Tuesday, October 02, 2012

The Guggenheim's Greater Good Forum - Empathy

During the last week of September, The Guggenheim Museum in NYC hosted an online forum called The Greater Good - on empathy and related issues:

The forum was hosted by Lynne Soraya, who blogs at Psychology Today in her Asperger's Diary.

The forum was hosted by Lynne Soraya, who blogs at Psychology Today in her Asperger's Diary.

Participants:

Moderator, Lynne Soraya

Lynne Soraya (a pseudonym) is a writer, journalist, and disability advocate with Asperger’s Syndrome, a form of autism. She writes the Asperger's Diary blog for Psychology Today.

There were three sessions and then a live online question and answer session. Here is the first session, then I will provide links to the rest. Panelist, Meghan Falvey

Panelist, Meghan Falvey

Meghan Falvey is a writer whose work focuses on affective labor and inequality. Her writing has appeared in a number of publications, including n+1, The Brooklyn Rail, Modern Painters, and 3 Quarks Daily. Photo: Courtesy Meghan Falvey.

Panelist, G. Anthony Gorry

Panelist, G. Anthony Gorry

Tony Gorry is the Friedkin Chair of Management and Professor of Computer Science at Rice University and an Adjunct Professor of Neuroscience at Baylor College of Medicine. He is a member of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences. Photo: Courtesy G. Anthony Gorry.

Panelist, Peggy Mason

Peggy Mason is a Professor of Neurobiology at the University of Chicago. She is the author of Medical Neurobiology (2011), a textbook for medical students. Her recent work, establishing that rats recognize and act deliberately to relieve the distress of another individual, has garnered worldwide attention. Photo: Courtesy Peggy Mason.

Session 1

Moderator

Lynne Soraya

One day, I picked up my smartphone and popped Twitter open. Two tweets about empathy caught my eye, one stacked on top of the other. The first text discussed how people with autism lack empathy. The second read, “Rats have empathy, study finds.”

I laughed. This pastiche of scientific concepts unintentionally portrayed a topsy-turvy world. Autistic human beings lacked an ability that rats apparently practiced with ease. Was this science’s real message?

I was reminded of one my favorite humor pieces, Richard Lederer’s “The World According to Student Bloopers,” a distorted, but often hilarious, account of world history compiled from student papers. I wondered: What if we created such a compilation from all of the materials published on empathy? What would that look like? What would it tell us about what we, as a society, think of empathy?

The two references I saw on Twitter that day were only two of the many ways we talk about empathy, and after reading them, I had to question whether the respective authors meant to convey the same thing. In the case of the rats, an altruistic act of releasing a trapped cagemate was said to indicate that they were capable of empathy. This suggests a definition akin to caring about others’ distress and acting to mitigate that distress.

Apply this particular model to people with autism; it’s hard to categorically say that they lack empathy. Take, for example, an incident related by Ralph James Savarese, in his book Reasonable People: A Memoir of Autism and Adoption (2007). Mr. Savarese’s nephew had recently passed away from cancer, and his sister was immersed in grief. Seeing her pain, Savarese’s nonverbal and profoundly autistic son, DJ, grabbed his typing machine and wrote a message to his aunt: “Do you have reasonable people to help you with your hurt?” To me, this seems to be an example consistent with the definition of empathy used by the authors of the rat study.

But is this the definition intended by the author of the tweet about autism? I don’t believe so. In autism research, empathy is often discussed with much more complexity. It involves not only caring about distress and acting to mitigate it but also concepts like “mind reading”—the ability to predict, or “read,” what others are thinking and feeling. If we apply this concept to the rat experience, can we claim that rats have empathy? Are they really going through the same higher order of reasoning that we ascribe to humans?

Reviewing only these two examples, I’m left with many questions: What exactly is empathy? Do we, as a society, define it consistently? By what metric can it be measured? Are there subtypes of empathy? Can it be broken down into different components—perhaps into concepts like “cognitive empathy” and “emotional empathy”?

Going a bit further: How do these conceptual differences in the definition of empathy affect how we talk about it, and apply it? What does it really mean to empathize with the subject of a portrait or work of art? Or, simply, what does it mean to empathize with another person that you meet on the street?

* * * * *PANELIST

Meghan Falvey

I agree that empathy is a slippery concept and one that gets used in sometimes confounding ways. A favorite example is the headline I saw on a CNBC post a few years ago, which read: "Is Your Empathy Killing Your Career?" I kept imagining the questions on the inevitable quiz.

Despite the ruthlessness and competitive behavior that capitalist economics rewards—unexpectedly the Texan sage Rick Perry comes to mind, in the form of the phrase “vulture capitalism”—employees have been encouraged to develop and display empathy in their work relations since Dale Carnegie’s 1937 How to Win Friends and Influence People. The sociologist Eva Illouz has looked at Carnegie’s claim that "[developing empathy] may easily prove to be one of the milestones of your career." Illouz suggests that the management theory that underlies corporate labor relations (and, indeed, has replaced that term with the less contentious "human resources") has consistently relied on techniques of emotional management. Management psychology's interest in emotions and affect tends to lean toward advice on how to marshal them for strategic deployment. In this context, it seems signal that empathy should be universally encouraged. I think that's partly why the CNBC headline sounds funny.

This leads us back to your question about what exactly is meant by the term “empathy.” In the case of workplace relations it seems to denote something that is, in fact, quite self-centered: the ability to accurately gauge how one appears to others. Given that the general understanding of empathy assumes a positive valence—that empathy is linked to altruism, sympathy, and compassion, affects people usually congratulate themselves for possessing—it's interesting to consider it as a morally neutral force. The understanding of empathy that seems at use in the workplace is one that explicitly regards the individual self to be a kind of citadel and takes other people—one's co-workers, boss and subordinate alike—to be pawns, nuisances, or even threats outside its gates.

The rest of the online forum:* * * * *PANELIST

G. Anthony Gorry

Two hundred years ago, Adam Smith spoke of our "fellow feeling," which stirs "pity for the sorrowful, anguish for the miserable, joy for the successful.” This reaction to others, which we now generally call empathy, emerged countless years ago as natural selection forged our remarkable human sociability, our nuanced involvement with one another. Recently, neuroscientists have identified emotional centers in our brains that engender empathy, that make us exquisitely sensitive to the observed joy, pain or suffering of others. Hundreds of thousands of years removed from the savannah, we still instinctively wince seeing another's hand struck by a hammer; tilt our own bodies, watching another teetering on a balance; gag, seeing someone else eat something disgusting; choke up, recognizing suffering in another. We respond not only to gross actions but also to the twitch of an eye, tremor of a hand, tensing of a leg, even the dilation of a pupil—all subtle indicators of the intent of the brain within the body observed.

As Smith noted, our highly developed imagination is a powerful adjunct to these responses. Recently, J. K. Rowling echoed Smith when she said that imagination is the “power that enables us to empathize with humans whose experiences we have never shared . . . Unlike any other creature on this planet, humans can learn and understand, without having experienced. They can think themselves into other people's minds, imagine themselves into other people's places." Neural circuits drive the apparent altruism of the rat and the apparent concern of the autistic, but neither is likely to imagine standing “in the shoes of another” as Adam Smith would have had it.

For millennia, stories have put us in those shoes. Today books, movies, television, and the Internet all feed our hunger to learn about others, to share their experiences, to empathize with them. We so enjoy stories, we gossip about people we don’t know, inventing stories of their lives for our own pleasure. Every day we see the interplay of empathy, imagination, and storytelling in our families, our neighborhoods, at work, anywhere people gather.

The extent to which ordinary individuals empathize with their compatriots, however, may vary markedly. For each person who seems naturally sensitive to the feelings, experiences, and stories of others, another may appear almost indifferent. Then, too, the extent to which we have been taught to adopt the perspectives of others—to make their concerns our own and to react as they do—affects our reactions to their circumstances. Those who claim that novels can edify their readers argue that fiction can teach us to care for the orphan and rejoice in the triumphs of the once downtrodden. On the other hand, impediments to action—the feeling, for example, that one can do nothing for the person in need—can stifle empathetic response.

Digital technology increasingly mediates our interactions with others. Life on the screen is reshaping storytelling and thus affecting the way in which the experiences of others, real and imagined, stir the empathetic centers that lie deep within us.* * * * *PANELIST

Peggy MasonFundamental to all definitions of empathy is communication of an emotional or affective state between individuals. The eminent primatologist Frans de Waal considers being affected by another’s emotional state as a primitive form of empathy, which I believe is a useful starting point. Such social communication of affect need not be conscious and typically is not. Rather than rely on “higher order reasoning,” basic forms of empathy depend on neural pathways that are shared with other mammals. Passing a person who cheerfully smiles at us makes us feel happier and more likely to smile. We don’t reason through this process; it just happens. Such affective resonance is essential social communication that “works” in any culture independent of words, explanations, or abstract thought. These automatic emotional responses serve as social glue, biasing a group of individuals toward emotional consensus.As defined above, empathy is a neutral term. Responding to another’s affective state, mood, or emotion does not constrain the actions taken, if any, as a result. Hopefully, seeing another individual in distress induces most to offer comfort or help. However, recognizing another’s emotional state can be used for nefarious purposes, for example to take advantage of emotionally vulnerable people. What we all want to see is empathic concern, an other-oriented emotional response elicited by and congruent with the perceived welfare of an individual in distress. By adding in the response that is congruent with the welfare of the other, this definition precludes antisocial actions; the action taken by an individual feeling empathic concern is pro-social in nature.

The path to empathic helping is difficult. A potential helper must recognize the distress of another individual while suppressing personal distress in order to act rather than freeze in panic. Finally, the individual motivated to help must figure out what to do. Empathic helping is sufficiently beneficial to survival that mammals have evolved this capacity.

Most humans, like most rats, show empathy, whereas a minority of humans and rats do not display empathic helping. For rats, figuring out how to release a trapped rat is difficult, meaning the motor know-how is a major hurdle that some rats do not get over. Other rats appear unable to suppress their own distress enough to act. I do not know at which point some individuals with autism get stuck. Perhaps some autistic people can’t recognize another’s distress, while others become too overwhelmed by it to act, or have a language impairment that prevents a response. Maybe some individuals with autism are in fact empathic; certainly the actions of DJ reflect great empathy, albeit oddly expressed.

Although rats and mammals share the capacity for empathy with humans, the experiences are surely not the same. Even among humans, internal experiences are spectacularly individual, defining unique. The uniqueness of experience holds true for perceptions, thoughts and emotions. So if all of us humans live our own unique experiences, what are the chances that a rat experiences empathy the same as does a human? Nil. No chance.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)