These powerful stories shatter preconceived notions about mental illness, and pose the provocative question: What can the world learn from different kinds of minds?

Playlist (9 talks)

14:52 - Elyn Saks A tale of mental illness -- from the inside

"Is it okay if I totally trash your office?" It's a question Elyn Saks once asked her doctor, and it wasn't a joke. A legal scholar, in 2007 Saks came forward with her own story of schizophrenia, controlled by drugs and therapy but ever-present. In this powerful talk, she asks us to see people with mental illness clearly, honestly and compassionately.

19:43 - Temple Grandin The world needs all kinds of minds

Temple Grandin, diagnosed with autism as a child, talks about how her mind works — sharing her ability to "think in pictures," which helps her solve problems that neurotypical brains might miss. She makes the case that the world needs people on the autism spectrum: visual thinkers, pattern thinkers, verbal thinkers, and all kinds of smart geeky kids.

14:17 - Eleanor Longden The voices in my head

To all appearances, Eleanor Longden was just like every other student, heading to college full of promise and without a care in the world. That was until the voices in her head started talking. Initially innocuous, these internal narrators became increasingly antagonistic and dictatorial, turning her life into a living nightmare. Diagnosed with schizophrenia, hospitalized, drugged, Longden was discarded by a system that didn't know how to help her. Longden tells the moving tale of her years-long journey back to mental health, and makes the case that it was through learning to listen to her voices that she was able to survive.

8:44 - Ruby Wax What's so funny about mental illness?

Diseases of the body garner sympathy, says comedian Ruby Wax — except those of the brain. Why is that? With dazzling energy and humor, Wax, diagnosed a decade ago with clinical depression, urges us to put an end to the stigma of mental illness.

22:18 - Sherwin Nuland How electroshock therapy changed me

Surgeon and author Sherwin Nuland discusses the development of electroshock therapy as a cure for severe, life-threatening depression — including his own. It’s a moving and heartfelt talk about relief, redemption and second chances.

5:51 - Joshua Walters On being just crazy enough

At TED's Full Spectrum Auditions, comedian Joshua Walters, who's bipolar, walks the line between mental illness and mental "skillness." In this funny, thought-provoking talk, he asks: What's the right balance between medicating craziness away and riding the manic edge of creativity and drive?

18:01 - Jon Ronson Strange answers to the psychopath test

Is there a definitive line that divides crazy from sane? With a hair-raising delivery, Jon Ronson, author of The Psychopath Test, illuminates the gray areas between the two. (With live-mixed sound by Julian Treasure and animation by Evan Grant.)

18:48 - Oliver Sacks What hallucination reveals about our minds

Neurologist and author Oliver Sacks brings our attention to Charles Bonnet syndrome — when visually impaired people experience lucid hallucinations. He describes the experiences of his patients in heartwarming detail and walks us through the biology of this under-reported phenomenon.

9:26 - Robert Gupta Music is medicine, music is sanity

Robert Gupta, violinist with the LA Philharmonic, talks about a violin lesson he once gave to a brilliant, schizophrenic musician — and what he learned. Called back onstage later, Gupta plays his own transcription of the prelude from Bach's Cello Suite No. 1.

Offering multiple perspectives from many fields of human inquiry that may move all of us toward a more integrated understanding of who we are as conscious beings.

Showing posts with label auditory hallucinations. Show all posts

Showing posts with label auditory hallucinations. Show all posts

Tuesday, November 11, 2014

TED Talk Playlist: All Kinds of Minds (9 Talks)

This is a cool collection of TED Talks entitled, "All kinds of minds." These nine talks "shatter" common beliefs and stereotypes about mental illness, or more accurately, neurodiversity.

Monday, September 15, 2014

Vaughan Bell - A Social Visit with Hallucinated Voices

In this brief article from the PLOS Neuroscience Community blog, Vaughan Bell looks at the experience of hallucinated voices and how the hearer responds to them. Most who experience voices conceptualize them as distinct entities in some way, often as people they knew or know.

This piece looks at the why of experiencing these voices as unique entities.

A Social Visit with Hallucinated Voices

September 8, 2014

By Vaughan Bell

I’ve met a lot of people who hear hallucinated voices and I have always been struck by the number of people who feel accompanied by them, as if they were distinct and distinguishable personalities. Some experience their hallucinated entourage as hecklers or domineering bullies, some as curious and opaque narrators, others as helpful guardians, but most of the time, the voice hearer feels they share a relationship with a series of internal vocal individuals. Not everyone who hears voices experiences them as social entities but this type of social hallucinated voice is not rare or exotic.

Studies show that the majority of voice hearers experience their voices as individuals who can be distinguished by the characteristics of their speech and even their personalities. For some, this means the voice is experienced as a specific person that others are aware of. It may be someone they know (perhaps a family member), a famous person, a religious figure, or even a fictional character from popular culture.

For others, the voices have an identity named solely by that person (“Jeremy, a little boy”), and sometimes, the voice is unnamed and just recognised by its personal characteristics like the “unknown old woman” or “a man with a deep voice”, as reported in a 1997 study by Leudar et al. Surprisingly, scientific theories of how auditory verbal hallucinations are formed have rarely attempted to explain this social, even personal, aspect of the experience.

Currently, the main scientific theories of voice hearing suggest that hallucinated voices occur through a combination of atypical activity in the language and memory systems of the brain and a tendency to attribute internally generated mental phenomena as coming from an external source. The idea is that voice hearers think phrases to themselves as part of their internal monologue but hear them as coming from outside due to problems with adequately distinguishing internally from externally generated experiences. There is lots of evidence from experimental studies to back up these theories, but they don’t really address the issue of how voices are perceived as social identities.

So how do internal thoughts become experienced as other people?

It seems not many people are interested. A recent paper, published in 2012, aimed to synthesise all the existing research to give an up-to-date cognitive model of how hallucinated voices occur, and had very little to say on how voices come to be perceived as social identities. This is most of it: “The content of AH [auditory hallucinations] may be determined by factors such as perceptual expectations, mental imagery, and prior experience/knowledge (e.g. memories) that shape a perception of reality that is idiosyncratic and highly personalized.” Considering that the personal nature of hallucinated voices is a central and defining feature for most voice hearers, this is a striking omission for a causal theory.

The paper I wrote for PLOS Biology, “A Community of One: Social Cognition and Auditory Verbal Hallucinations” aimed to encourage a better understanding of this issue for hallucinated voices by taking the aspect of social experience seriously and looking at the current evidence that would support a social cognitive and social neurocognitive theory for voice hearing.

As I point out in the paper, clinical psychologists in particular have looked a great deal at people’s social experience of voices.

Numerous studies have now found that voice hearers understand their connection with the voices in terms of relationships and interact with their voices in ways that “share many properties with interpersonal relationships within the social world” [6]. Most obvious in this regard is the fact that over 80% of people who experience auditory verbal hallucinations have reported that they are able to engage in interactive conversations with their voices [7],[8]. Judgments about the identity of hallucinated voices rely on perceptual features similar to those required to judge identity when listening to the voices of other speakers, with perceived identity being an important mediator of distress [11].But these findings haven’t been well integrated into research on auditory hallucination formation completed by experimental psychologists and neuroscientists who have tended to focus on individualistic, information processing theories. However, if you look at which neural circuits turn up in brain imaging studies, and how people perceive their voices in psychology studies, which is the evidence I review in detail in the paper, there is a good case for making social processing in the mind and brain a central part of understanding voices. I also suggest that one place to start making sense of this data could be in how we generate and use internal models of other ‘social actors’ when we’re thinking and reasoning about social situations.

Essentially, we spend a lot of time thinking about how certain people might react in certain situations, what they might say, and what they might do, even when they’re not present.

Here, again, from my PLOS Biology article:

It would be most parsimonious to assume that these phenomena stem from our normal ability to internalise models of people we know and their voices, rather than auditory hallucinations involving a de novo generation of persistent and internally vocal social identities. Accounts including internalised models of social actors suggest that we internalise others' voices and personalities so that we can predict what someone would say or do in any given situation [30]. These internal models can be for specific people, so I can imagine how my spouse might respond in a hypothetical conversation, or for generic stereotypes, so I can imagine how a policeman or shopkeeper might respond.A Different Approach

I argue it’s more likely that the content of hallucinated voices comes from a normal ability to internalise models of people we know and their voices, rather than involving a separate step when we re-interpret our own thoughts as being from a range of individual characters based on some vague notion of ‘perceptual expectations’.In the (PLOS Biology) article, I also make a series of predictions as to what this approach would entail. If you’re not familiar with science, making a series of predictions is research talk for ‘come and have a go if you think you’re hard enough’ based on the collective belief that reality ends up kicking everyone’s ass.

As a result, I’ve begun working with people who want to knock the ideas into shape or who are interested in stress testing similar concepts. I’ve been working on the role of agent representation – essentially how we make sense of other autonomous beings in the world and how we understand them in terms of their choices, actions and mental states – and how it applies to hallucinations, with philosopher of mind Sam Wilkinson. We’re just finishing a paper so hopefully we can continue the debate and spark some new approaches to hallucinations. We’re also working on the scientific implications with two cognitive neuroscientists who are much cleverer (and harder) than me, but we’re still getting our first draft of the paper down, so I’ll wait to we’ve got the details hammered out to say a bit more.

Finally, there is something important to note in how causal models of hallucinated voices have tended to ignore content and personal significance as irrelevant, while clinical models have tended to ignore neurocognition as inconsequential.

This is a trend present to varying extents throughout psychopathology research and it tends to distance lived experience from an integrated scientific approach to an experience that needs to be better addressed when distressing or disabling, and better understood as part of human nature.We need to develop an understanding of difficult experiences that span mind and brain and ensure that clinicians, psychologists and neuroscientists talk to each other more than they presently do.

Vaughan Bell is a neuropsychologist at Kings College London and a clinical psychologist at the Maudsley Hospital. He blogs at MindHacks and serves as a PLOS ONE Academic Editor. On Twitter @VaughanBell

Click here to listen to “Hallucinations and Designer Drugs,” an August 2013 Mind the Brain Podcast interview with Vaughan Bell, conducted by former PLOS Biology Senior Editor Ruchir Shah.

Monday, August 25, 2014

Novel 'Avatar Therapy' May Silence Voices in Schizophrenia

Interesting. It's always good to see a non-drug approach to dealing with the symptoms of psychosis. I would like to see a larger study on this, and some way to make it scalable for therapists who don't have the resources to to do it in the same way as the study.

Below is a summary of the study from Medscape Medical News, and below the summary is the abstract for the full article, which is open access (follow the link below).

Full Citation:

Leff, J, Williams, G, Huckvale, M, Arbuthnot, M, & Leff, AP. (2014). Avatar therapy for persecutory auditory hallucinations: What is it and how does it work? Psychosis; 6:166-176. DOI: 10.1080/17522439.2013.773457

Novel 'Avatar Therapy' May Silence Voices in Schizophrenia

Deborah Brauser

July 03, 2014

LONDON ― A novel treatment may help patients with schizophrenia confront and even silence the internal persecutory voices they hear, new research suggests.

Avatar therapy allows patients to choose a digital face (or "avatar") that best resembles what they picture their phantom voice to look like. Then, after discussing ahead of time the things the voice often says to the patient, a therapist sits in a separate room and "talks" through the animated avatar shown on a computer monitor in a disguised and filtered voice as it interacts with the patient.

In addition, the therapist can also talk by microphone in a normal voice to coach the patient throughout each session.

In a pilot study of 26 patients with treatment-resistant psychosis who reported auditory hallucinations, those who received 6 half-hour sessions of avatar therapy reported a significant reduction in the frequency and volume of the internal voices ― and 3 reported that the voices had disappeared altogether.

"Opening up a dialogue between a patient and the voice they've been hearing is powerful. This is a way to talk to it instead of only hearing 1-way conversations," lead author and creator of the therapy program Julian Leff, MD, FRCPsych, emeritus professor at the Institute of Psychiatry in London, told meeting attendees.

Dr. Julian Leff

"As the therapist, I'm sharing the patient's experience and can actually hear what the patient hears. But it's important to remind them that this is something that they created and that they are in a safe space," Dr. Leff told Medscape Medical News after his presentation.

Two presentations were given here at the International Congress of the Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCPsych) 2014 the day after the study results were released in the print edition of Psychosis.

Regaining Control

According to the investigators, 1 in 4 people who hear phantom voices fail to respond to antipsychotic medication.

Dr. Leff explained that this program started a little more than 3 years ago, after he had retired "and could start thinking clearly again." He had been interested in the phenomenon of phantom voices for more than 40 years.

"Our mind craves meaningful input. That's its nourishment. And if it's deprived of nourishment, it pushes out something into the outside world," he said. "The aim of our therapy is to give the patient's ego back its mastery over lost provinces of his mental life."

The researchers used the "off-shelf programs" Facegen for the creation of the avatar faces and Annosoft LIP-SYNC for animating the lips and mouth. They also used a novel real-time voice-morphing program for the voice matching and to let the voice of a therapist to be changed.

In fact, Dr. Leff reported that one option the program provided changed his voice into that of a woman.

After a patient chose a face/avatar from among several options, the investigators could change that face. For example, 1 patient spoke of hearing an angel talk to him but also talked about wanting to live in a world of angels. So the researchers made the avatar very stern and grim so that the patient would be more willing to confront it.

Another patient chose a "red devil" avatar and a low, booming voice to represent the aggressiveness that he had been hearing for 16 years.

For the study, 26 participants between the ages of 14 and 74 years (mean age, 37.7 years; 63% men) were selected and randomly assigned to receive either avatar therapy or treatment as usual with antipsychotic medication.

Dr. Julian Leff shows examples of faces used in avatar therapy at RCPsych 2014.

Dr. Julian Leff shows examples of faces used in avatar therapy at RCPsych 2014.

The length of time for hearing voices ranged from 3.5 years to more than 30 years, and all of the patients had very low self-esteem. Those who heard more than 1 voice were told to choose the one that was most dominant.

Pocket Therapist

During the sessions, the therapist sat in a separate room and played dual roles. He coached the participants on how to confront and talk with the avatars in his own voice, and he also voiced the avatars. All of the sessions were recorded and given to the participants on an MP3 recorder to play back if needed, to remind the patients how to confront and talk to the auditory hallucination if it reappeared.

"We told them: It's like having a therapist in your pocket. Use it," said Dr. Leff.

All of the avatars started out appearing very stern; they talked loudly and said horrible things to match what the patients had been reportedly experiencing. But after patients learned to talk back to the faces in more confident tones, the avatars began to "soften up" and discuss issues rationally and even offer advice.

Most of the participants who received avatar therapy went on after the study to be able to start new jobs. In addition, most reported that the voices went down to whispers, and 3 patients reported that the voices stopped completely.

The patient who confronted the red devil avatar reported that the voice had disappeared after 2 sessions. At the 3-month follow-up, he reported that the voice had returned, although at night only; he was told to go to bed earlier (to fight possible fatigue) and to use the MP3 player immediately beforehand. On all subsequent follow-ups, he reported that the voice was completely gone, and he has since gone on to work abroad.

Another patient who reported past experiences of abuse asked that his avatar be created wearing sunglasses because he could not bear to look at its eyes. During his sessions, Dr. Leff told him through the avatar that what had happened to the patient was not his fault. And at the end of 5 sessions, the phantom voice disappeared altogether.

Although 1 female patient reported that her phantom voice had not gone away, it had gotten much quieter. "When we asked her why, she said, 'The voice now knows that if it talks to me, I'll talk back,' " said Dr. Leff.

"These people are giving a face to an incredibly destructive force in their mind. Giving them control to create the avatar lets them control the situation and even make friends with it," he added.

"The moment that a patient says something and the avatar responds differently than before, everything changes."

In addition, there was a significant reduction in depression scores on the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia and in suicidal ideation for the avatar participants at the 3-month follow-up assessment.

A bigger study with a proposed sample size of 140 is currently under way and is "about a quarter of the way complete," Dr. Leff reports. Of these patients, 70 will receive avatar therapy, and 70 will receive supportive counseling.

"In order for others to master this therapy, it is necessary to construct a treatment manual and this has now been completed, in preparation for the replication study," write the investigators.

"One of its main aims is to determine whether clinicians working in a standard setting can be trained to achieve results comparable to those that emerged from the pilot study," they add.

"Fascinating" New Therapy

"I think this is really exciting. It's a fascinating, new form of therapy," session moderator Sridevi Kalidindi, FRCPsych, consultant psychiatrist and clinical lead in rehabilitation at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust in the United Kingdom, told Medscape Medical News.

Dr. Sridevi Kalidindi

"I think it is a novel way of approaching these very challenging symptoms that people have. From the early results that have been presented, it provides hope for people that they may actually be able to improve from all of these symptoms. And we may be able to reduce their distress in quite a different way from anything we've ever done before."

Dr. Kalidindi, who is also chair of the Rehabilitation Faculty for the Royal College of Psychiatrists, was not involved with this research.

She added that she will be watching this ongoing program "with great interest."

"I was very enthused to learn that more research is going on with this particularly complex group," said Dr. Kalidindi.

"This could be something for people who have perhaps not benefitted from other types of intervention. Overall, it's fantastic."

International Congress of the Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCPsych) 2014. Presented in 2 oral sessions on June 26, 2014.

Medscape Medical News © 2014 WebMD, LLC

* * * * *

Avatar therapy for persecutory auditory hallucinations: What is it and how does it work?

Open access

Julian Leff, Geoffrey Williams, Mark Huckvale, Maurice Arbuthnot & Alex P. Leff

Abstract

We have developed a novel therapy based on a computer program, which enables the patient to create an avatar of the entity, human or non-human, which they believe is persecuting them. The therapist encourages the patient to enter into a dialogue with their avatar, and is able to use the program to change the avatar so that it comes under the patient’s control over the course of six 30-min sessions and alters from being abusive to becoming friendly and supportive. The therapy was evaluated in a randomised controlled trial with a partial crossover design. One group went straight into the therapy arm: “immediate therapy”. The other continued with standard clinical care for 7 weeks then crossed over into Avatar therapy: “delayed therapy”. There was a significant reduction in the frequency and intensity of the voices and in their omnipotence and malevolence. Several individuals had a dramatic response, their voices ceasing completely after a few sessions of the therapy. The average effect size of the therapy was 0.8. We discuss the possible psychological mechanisms for the success of Avatar therapy and the implications for the origins of persecutory voices.

Hallucinatory 'Voices' Shaped by Local Culture

Stanford anthropologist Tanya Luhrmann studies the phenomena of voices in people diagnosed with psychosis. In a new study, published in the British Journal of Psychiatry (BJP), she and her team interviewed American subjects who here voices, as well people from Ghana and India.

Subjects were asked how many voices they heard, how often, what they thought caused the auditory hallucinations, and what their voices were like. The differences were striking.

However, I suspect that the way our culture creates the experiences of voices (as a product of trauma) is why the voices are so negative and sometimes violent. In non-Western cultures schizophrenia and psychosis have much better prognoses (Kulhara, 1994; Hopper & Wanderling, 2000; Jilek, 2001) than in the West where schizophrenia is seen as a life-long illness.

References

Kulhara P. (1994). Outcome of schizophrenia: some transcultural observations with particular reference to developing countries. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci.; 244(5):227-35.

Hopper, K,

Wanderling, J. (2000). Revisiting the developed versus developing country

distinction in course and outcome in schizophrenia: results from ISoS,

the WHO collaborative follow up project. International Study of

Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin; 26(4): 835–46. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033498. PMID 11087016.

Jilek, WG. (2001). Cultural Factors in Psychiatric Disorders. Paper presented at the 26th Congress of the World Federation for Mental Health, July 2001.

Full Citation:

Luhrmann, TM, Padmavati, R, Tharoor, H, and Osei, A. (2014, Jun 26). Differences in voice-hearing experiences of people with psychosis in the USA, India and Ghana: Interview-based study. British J of Psychiatry; Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.139048

Subjects were asked how many voices they heard, how often, what they thought caused the auditory hallucinations, and what their voices were like. The differences were striking.

The striking difference was that while many of the African and Indian subjects registered predominantly positive experiences with their voices, not one American did. Rather, the U.S. subjects were more likely to report experiences as violent and hateful – and evidence of a sick condition.For those subjects who were not American, the voices were decidedly different:

The Americans experienced voices as bombardment and as symptoms of a brain disease caused by genes or trauma.

Among the Indians in Chennai, more than half (11) heard voices of kin or family members commanding them to do tasks. "They talk as if elder people advising younger people," one subject said. ... Also, the Indians heard fewer threatening voices than the Americans – several heard the voices as playful, as manifesting spirits or magic, and even as entertaining. Finally, not as many of them described the voices in terms of a medical or psychiatric problem, as all of the Americans did.How different would the experience of psychosis be in this country if we took a different view on the voices that often come with PTSD and psychosis?

However, I suspect that the way our culture creates the experiences of voices (as a product of trauma) is why the voices are so negative and sometimes violent. In non-Western cultures schizophrenia and psychosis have much better prognoses (Kulhara, 1994; Hopper & Wanderling, 2000; Jilek, 2001) than in the West where schizophrenia is seen as a life-long illness.

References

Kulhara P. (1994). Outcome of schizophrenia: some transcultural observations with particular reference to developing countries. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci.; 244(5):227-35.

Jilek, WG. (2001). Cultural Factors in Psychiatric Disorders. Paper presented at the 26th Congress of the World Federation for Mental Health, July 2001.

Hallucinatory 'voices' shaped by local culture, Stanford anthropologist says

Stanford Report, July 16, 2014

By Clifton B. Parker

Stanford anthropologist Tanya Luhrmann found that voice-hearing experiences of people with serious psychotic disorders are shaped by local culture – in the United States, the voices are harsh and threatening; in Africa and India, they are more benign and playful. This may have clinical implications for how to treat people with schizophrenia, she suggests.

Tanya Luhrmann, professor of anthropology, studies how culture affects the experiences of people who experience auditory hallucinations, specifically in India, Ghana and the United States.

People suffering from schizophrenia may hear "voices" – auditory hallucinations – differently depending on their cultural context, according to new Stanford research.

In the United States, the voices are harsher, and in Africa and India, more benign, said Tanya Luhrmann, a Stanford professor of anthropology and first author of the article in the British Journal of Psychiatry.

The experience of hearing voices is complex and varies from person to person, according to Luhrmann. The new research suggests that the voice-hearing experiences are influenced by one's particular social and cultural environment – and this may have consequences for treatment.

In an interview, Luhrmann said that American clinicians "sometimes treat the voices heard by people with psychosis as if they are the uninteresting neurological byproducts of disease which should be ignored. Our work found that people with serious psychotic disorder in different cultures have different voice-hearing experiences. That suggests that the way people pay attention to their voices alters what they hear their voices say. That may have clinical implications."

Positive and negative voices

Luhrmann said the role of culture in understanding psychiatric illnesses in depth has been overlooked.

"The work by anthropologists who work on psychiatric illness teaches us that these illnesses shift in small but important ways in different social worlds. Psychiatric scientists tend not to look at cultural variation. Someone should, because it's important, and it can teach us something about psychiatric illness," said Luhrmann, an anthropologist trained in psychology. She is the Watkins University Professor at Stanford.

For the research, Luhrmann and her colleagues interviewed 60 adults diagnosed with schizophrenia – 20 each in San Mateo, California; Accra, Ghana; and Chennai, India. Overall, there were 31 women and 29 men with an average age of 34. They were asked how many voices they heard, how often, what they thought caused the auditory hallucinations, and what their voices were like.

"We then asked the participants whether they knew who was speaking, whether they had conversations with the voices, and what the voices said. We asked people what they found most distressing about the voices, whether they had any positive experiences of voices and whether the voice spoke about sex or God," she said.

The findings revealed that hearing voices was broadly similar across all three cultures, according to Luhrmann. Many of those interviewed reported both good and bad voices, and conversations with those voices, as well as whispering and hissing that they could not quite place physically. Some spoke of hearing from God while others said they felt like their voices were an "assault" upon them.

'Voices as bombardment'

The striking difference was that while many of the African and Indian subjects registered predominantly positive experiences with their voices, not one American did. Rather, the U.S. subjects were more likely to report experiences as violent and hateful – and evidence of a sick condition.

The Americans experienced voices as bombardment and as symptoms of a brain disease caused by genes or trauma.

One participant described the voices as "like torturing people, to take their eye out with a fork, or cut someone's head and drink their blood, really nasty stuff." Other Americans (five of them) even spoke of their voices as a call to battle or war – "'the warfare of everyone just yelling.'"

Moreover, the Americans mostly did not report that they knew who spoke to them and they seemed to have less personal relationships with their voices, according to Luhrmann.

Among the Indians in Chennai, more than half (11) heard voices of kin or family members commanding them to do tasks. "They talk as if elder people advising younger people," one subject said. That contrasts to the Americans, only two of whom heard family members. Also, the Indians heard fewer threatening voices than the Americans – several heard the voices as playful, as manifesting spirits or magic, and even as entertaining. Finally, not as many of them described the voices in terms of a medical or psychiatric problem, as all of the Americans did.

In Accra, Ghana, where the culture accepts that disembodied spirits can talk, few subjects described voices in brain disease terms. When people talked about their voices, 10 of them called the experience predominantly positive; 16 of them reported hearing God audibly. "'Mostly, the voices are good,'" one participant remarked.

Individual self vs. the collective

Why the difference? Luhrmann offered an explanation: Europeans and Americans tend to see themselves as individuals motivated by a sense of self identity, whereas outside the West, people imagine the mind and self interwoven with others and defined through relationships.

"Actual people do not always follow social norms," the scholars noted. "Nonetheless, the more independent emphasis of what we typically call the 'West' and the more interdependent emphasis of other societies has been demonstrated ethnographically and experimentally in many places."

As a result, hearing voices in a specific context may differ significantly for the person involved, they wrote. In America, the voices were an intrusion and a threat to one's private world – the voices could not be controlled.

However, in India and Africa, the subjects were not as troubled by the voices – they seemed on one level to make sense in a more relational world. Still, differences existed between the participants in India and Africa; the former's voice-hearing experience emphasized playfulness and sex, whereas the latter more often involved the voice of God.

The religiosity or urban nature of the culture did not seem to be a factor in how the voices were viewed, Luhrmann said.

"Instead, the difference seems to be that the Chennai (India) and Accra (Ghana) participants were more comfortable interpreting their voices as relationships and not as the sign of a violated mind," the researchers wrote.

Relationship with voices

The research, Luhrmann observed, suggests that the "harsh, violent voices so common in the West may not be an inevitable feature of schizophrenia." Cultural shaping of schizophrenia behavior may be even more profound than previously thought.

The findings may be clinically significant, according to the researchers. Prior research showed that specific therapies may alter what patients hear their voices say. One new approach claims it is possible to improve individuals' relationships with their voices by teaching them to name their voices and to build relationships with them, and that doing so diminishes their caustic qualities. "More benign voices may contribute to more benign course and outcome," they wrote.

Co-authors for the article included R. Padmavati and Hema Tharoor from the Schizophrenia Research Foundation in Chennai, India, and Akwasi Osei from the Accra General Psychiatric Hospital in Accra, Ghana.

What's next in line for Luhrmann and her colleagues?

"Our hunch is that the way people think about thinking changes the way they pay attention to the unusual experiences associated with sleep and awareness, and that as a result, people will have different spiritual experiences, as well as different patterns of psychiatric experience," she said, noting a plan to conduct a larger, systematic comparison of spiritual, psychiatric and thought process experiences in five countries.

Media Contact

- Tanya Luhrmann, Anthropology: (650) 521 1243 or (650) 723-3421, luhrmann@stanford.edu

- Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: 650-725-0224, cbparker@stanford.edu

* * * * *

Full Citation:

Luhrmann, TM, Padmavati, R, Tharoor, H, and Osei, A. (2014, Jun 26). Differences in voice-hearing experiences of people with psychosis in the USA, India and Ghana: Interview-based study. British J of Psychiatry; Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.139048

Differences in voice-hearing experiences of people with psychosis in the USA, India and Ghana: Interview-based study

T. M. Luhrmann, R. Padmavati, H. Tharoor and A. Osei

Background

We still know little about whether and how the auditory hallucinations associated with serious psychotic disorder shift across cultural boundaries.

Aims

To compare auditory hallucinations across three different cultures, by means of an interview-based study.

Method

An anthropologist and several psychiatrists interviewed participants from the USA, India and Ghana, each sample comprising 20 persons who heard voices and met the inclusion criteria of schizophrenia, about their experience of voices.

Results

Participants in the USA were more likely to use diagnostic labels and to report violent commands than those in India and Ghana, who were more likely than the Americans to report rich relationships with their voices and less likely to describe the voices as the sign of a violated mind.

Conclusions

These observations suggest that the voice-hearing experiences of people with serious psychotic disorder are shaped by local culture. These differences may have clinical implications.

Wednesday, June 11, 2014

Does "22q11 Deletion Syndrome" Set the Stage for the 'Voices' that Are Symptom of Schizophrenia

There has never, so far, been a convincing genetic link for schizophrenia, until now. People who have the human genetic disorder 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. The syndrome occurs when part of chromosome 22, near the middle, is deleted and individuals are left with one rather than the usual two copies of about 25 genes.

Here is some more from the NIH "Genetics Home Reference":

22q11.2 deletion syndrome has many possible signs and symptoms that can affect almost any part of the body. The features of this syndrome vary widely, even among affected members of the same family. Common signs and symptoms include heart abnormalities that are often present from birth, an opening in the roof of the mouth (a cleft palate), and distinctive facial features. People with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome often experience recurrent infections caused by problems with the immune system, and some develop autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis and Graves disease in which the immune system attacks the body's own tissues and organs. Affected individuals may also have breathing problems, kidney abnormalities, low levels of calcium in the blood (which can result in seizures), a decrease in blood platelets (thrombocytopenia), significant feeding difficulties, gastrointestinal problems, and hearing loss. Skeletal differences are possible, including mild short stature and, less frequently, abnormalities of the spinal bones.An estimated 1 in 4,000 people have 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. About 30 percent of individuals with the deletion syndrome develop schizophrenia, making it one of the strongest risk factors for the disorder

Many children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome have developmental delays, including delayed growth and speech development, and learning disabilities. Later in life, they are at an increased risk of developing mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder. Additionally, affected children are more likely than children without 22q11.2 deletion syndrome to have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and developmental conditions such as autism spectrum disorders that affect communication and social interaction.

Because the signs and symptoms of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome are so varied, different groupings of features were once described as separate conditions. Doctors named these conditions DiGeorge syndrome, velocardiofacial syndrome (also called Shprintzen syndrome), and conotruncal anomaly face syndrome. In addition, some children with the 22q11.2 deletion were diagnosed with the autosomal dominant form of Opitz G/BBB syndrome and Cayler cardiofacial syndrome. Once the genetic basis for these disorders was identified, doctors determined that they were all part of a single syndrome with many possible signs and symptoms. To avoid confusion, this condition is usually called 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, a description based on its underlying genetic cause.

For the sake of reference, about 1 in 100 people will develop schizophrenia, 1.1%, while the rate the deletion syndrome is .00025%. Clearly, there are a LOT of people presenting with schizophrenia who do not have the deletion syndrome.

This syndrome apparently can cause increased expression of Drd2 in the thalamus, and Drd2 is associated with D2 dopamine receptors. The researchers identified a specific disruption of synaptic transmission at thalamocortical glutamatergic projections in the auditory cortex in mouse models of schizophrenia-associated 22q11 deletion syndrome (22q11DS). This deficit is caused by an unusual elevation of Drd2 in the thalamus, which renders 22q11DS thalamocortical projections sensitive to antipsychotics.

The downside of this research is that there will be new drugs developed to target the voices heard by those with schizophrenia, despite mounting evidence that befriending the voices is better long-term solution than psychopharmacological interventions.

Here is the abstract from Science - the article itself is behind the usual pay wall.Brain circuit problem likely sets stage for the 'voices' that are symptom of schizophrenia

Date: June 5, 2014

Source: St. Jude Children's Research Hospital

Summary: Scientists have identified problems in a connection between brain structures that may predispose individuals to hearing the 'voices' that are a common symptom of schizophrenia. Researchers linked the problem to a gene deletion. This leads to changes in brain chemistry that reduce the flow of information between two brain structures involved in processing auditory information.

Conceptual illustration (stock image). Scientists have identified problems in a connection between brain structures that may predispose individuals to hearing the "voices" that are a common symptom of schizophrenia. Credit: © yalayama / Fotolia

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital scientists have identified problems in a connection between brain structures that may predispose individuals to hearing the "voices" that are a common symptom of schizophrenia. The work appears in the June 6 issue of the journal Science.

Researchers linked the problem to a gene deletion. This leads to changes in brain chemistry that reduce the flow of information between two brain structures involved in processing auditory information.

The research marks the first time that a specific circuit in the brain has been linked to the auditory hallucinations, delusions and other psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia. The disease is a chronic, devastating brain disorder that affects about 1 percent of Americans and causes them to struggle with a variety of problems, including thinking, learning and memory.

The disrupted circuit identified in this study solves the mystery of how current antipsychotic drugs ease symptoms and provides a new focus for efforts to develop medications that quiet "voices" but cause fewer side effects.

"We think that reducing the flow of information between these two brain structures that play a central role in processing auditory information sets the stage for stress or other factors to come along and trigger the 'voices' that are the most common psychotic symptom of schizophrenia," said the study's corresponding author Stanislav Zakharenko, M.D., Ph.D., an associate member of the St. Jude Department of Developmental Neurobiology. "These findings also integrate several competing models regarding changes in the brain that lead to this complex disorder."

The work was done in a mouse model of the human genetic disorder 22q11 deletion syndrome. The syndrome occurs when part of chromosome 22 is deleted and individuals are left with one rather than the usual two copies of about 25 genes. About 30 percent of individuals with the deletion syndrome develop schizophrenia, making it one of the strongest risk factors for the disorder. DNA is the blueprint for life. Human DNA is organized into 23 pairs of chromosomes that are found in nearly every cell.

Earlier work from Zakharenko's laboratory linked one of the lost genes, Dgcr8, to brain changes in mice with the deletion syndrome that affect a structure important for learning and memory. They found evidence that the same mechanism was at work in patients with schizophrenia. Dgcr8 carries instructions for making small molecules called microRNAs that help regulate production of different proteins.

For this study, researchers used state-of-the-art tools to link the loss of Dgcr8 to changes that affect a different brain structure, the auditory thalamus. For decades antipsychotic drugs have been known to work by binding to a protein named the D2 dopamine receptor (Drd2). The binding blocks activity of the chemical messenger dopamine. Until now, however, how that quieted the "voices" of schizophrenia was unclear.

Working in mice with and without the 22q11 deletion, researchers showed that the strength of the nerve impulse from neurons in the auditory thalamus was reduced in mice with the deletion compared to normal mice. Electrical activity in other brain regions was not different.

Investigators showed that Drd2 levels were elevated in the auditory thalamus of mice with the deletion, but not in other brain regions. When researchers checked Drd2 levels in tissue from the same structure collected from 26 individuals with and without schizophrenia, scientists reported that protein levels were higher in patients with the disease.

As further evidence of Drd2's role in disrupting signals from the auditory thalamus, researchers tested neurons in the laboratory from different brain regions of mutant and normal mice by adding antipsychotic drugs haloperidol and clozapine. Those drugs work by targeting Drd2. Originally nerve impulses in the mutant neurons were reduced compared to normal mice. But the nerve impulses were almost universally enhanced by antipsychotics in neurons from mutant mice, but only in neurons from the auditory thalamus.

When researchers looked more closely at the missing 22q11 genes, they found that mice that lacked the Dgcr8 responded to a loud noise in a similar manner as schizophrenia patients. Treatment with haloperidol restored the normal startle response in the mice, just as the drug does in patients.

Studying schizophrenia and other brain disorders advances understanding of normal brain development and the missteps that lead to various catastrophic diseases, including pediatric brain tumors and other problems.

The study's first author is Sungkun Chun, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in Zakharenko's laboratory. The other authors are Joby Westmoreland, Ildar Bayazitov, Donnie Eddins, Amar Pani, Richard Smeyne, Jing Yu and Jay Blundon, all of St. Jude.

The research was funded in part by grants (MH097742, MH095810, DC012833) from the National Institutes of Health and ALSAC.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by St. Jude Children's Research Hospital. Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.

Journal Reference:

S. Chun, J. J. Westmoreland, I. T. Bayazitov, D. Eddins, A. K. Pani, R. J. Smeyne, J. Yu, J. A. Blundon, S. S. Zakharenko. (2014). Specific disruption of thalamic inputs to the auditory cortex in schizophrenia models. Science; 344(6188): 1178-1182. DOI: 10.1126/science.1253895

Specific disruption of thalamic inputs to the auditory cortex in schizophrenia models

Sungkun Chun, Joby J. Westmoreland, Ildar T. Bayazitov, Donnie Eddins, Amar K. Pani, Richard J. Smeyne, Jing Yu, Jay A. Blundon, Stanislav S. Zakharenko

ABSTRACT

Auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia are alleviated by antipsychotic agents that inhibit D2 dopamine receptors (Drd2s). The defective neural circuits and mechanisms of their sensitivity to antipsychotics are unknown. We identified a specific disruption of synaptic transmission at thalamocortical glutamatergic projections in the auditory cortex in murine models of schizophrenia-associated 22q11 deletion syndrome (22q11DS). This deficit is caused by an aberrant elevation of Drd2 in the thalamus, which renders 22q11DS thalamocortical projections sensitive to antipsychotics and causes a deficient acoustic startle response similar to that observed in schizophrenic patients. Haploinsufficiency of the microRNA-processing gene Dgcr8 is responsible for the Drd2 elevation and hypersensitivity of auditory thalamocortical projections to antipsychotics. This suggests that Dgcr8-microRNA-Drd2–dependent thalamocortical disruption is a pathogenic event underlying schizophrenia-associated psychosis.

Editor's Summary

Genes, synapses, and hallucinations

In a schizophrenia mouse model, Chun et al. found that an abnormal increase of dopamine D2 receptors in the brain's thalamic nuclei caused thalamocortical synapse deficits owing to reduced glutamate release. Antipsychotic agents or a dopamine receptor antagonist reversed this down-regulation. The defect was associated with the loss of a component of the microRNA processing machinery encoded by the dgcr8 gene.

Saturday, April 26, 2014

Inner Speech Is Not So Simple: A Commentary on Cho and Wu (2013)

This new article from Frontiers in Psychiatry: Schizophrenia is a response to Cho and Wu (2013) on their proposal for the mechanisms of auditory verbal hallucination (AVH) in schizophrenia.

Inner speech is not so simple: a commentary on Cho and Wu (2013)

Peter Moseley [1] and Sam Wilkinson [2]

1. Department of Psychology, Durham University, Durham, UKA commentary on

2. Department of Philosophy, Durham University, Durham, UK

Mechanisms of auditory verbal hallucination in schizophrenia

by Cho R, Wu W (2013). Front. Psychiatry 4:155. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00155

We welcome Cho and Wu’s (1) suggestion that the study of auditory verbal hallucinations (AVHs) could be improved by contrasting and testing more explanatory models. However, we have some worries both about their criticisms of inner speech-based self-monitoring (ISS) models and whether their proposed spontaneous activation (SA) model is explanatory.

Cho and Wu rightly point out that some phenomenological aspects of inner speech do not seem concordant with phenomenological aspects of AVH; Langdon et al. (2) found that, while many AVHs took the third person form (“he/she”), this was a relatively rare occurrence in inner speech, both for patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia who experienced AVHs and control participants. This is indeed somewhat problematic for ISS models, notwithstanding potential problems with the introspective measures used in the above study. However, Cho and Wu go on to ask: “how does inner speech in one’s own voice with its characteristic features become an AVH of, for example, the neighbor’s voice with its characteristic features?” (p. 2). Here, it seems that Cho and Wu simply assume that inner speech is always experienced in one’s own voice, and are not aware of research suggesting that the presence of other people’s voices is exactly the kind of quality reported in typical inner speech. For example, McCarthy-Jones and Fernyhough (3) showed that it is common for healthy, non-clinical participants to report hearing other voices as part of their inner speech, as well as to report their inner speech taking on the qualities of a dialogic exchange. This is consistent with Vygotskian explanations of the internalization of external dialogs during psychological development (4). In this light, no “transformation” from one’s own voice to that of another is needed, and no “additional mechanism” needs to be added to the ISS model (5).

In any case, this talk of transformation is misleading. There is no experience of inner speech first, which is then somehow transformed. The question about whether inner speech is implicated in AVHs is about whether elements involved in the production of inner speech experiences are also involved in the production of some AVHs. There seems to be fairly strong evidence to support this.

That inner speech involves motoric elements has been empirically supported by several electromyographical (EMG) studies [e.g., Ref. (6)]. Later experiments made the connection between inner speech and AVH, showing that similar muscular activation is involved in AVH (7, 8). The involvement of inner speech in AVH is further supported by the findings from Gould (9), who showed that when his subjects hallucinated, subvocalizations occurred which could be picked up with a throat microphone. These subvocalizations were causally responsible for the AVHs, and not just echoing them (as has been hypothesized to happen in some cases of verbal comprehension [cf. e.g., Ref. (10)]) was suggested by Bick and Kinsbourne (11), who demonstrated that if people experiencing hallucinations opened their mouths wide, stopping vocalizations, then the majority of AVHs stopped.

Cho and Wu argue that ISS models are no better than SA models at explaining the specificity of AVHs to specific voices and content; we would argue that an ISS model, with recognition that inner speech is more complex than one’s own voice speaking in the first person, explains more than the SA model, because it explains why voices with a specific phenomenology are experienced in the first place, as opposed to more random auditory experiences that might be expected from SA in auditory cortex. The appeal to individual differences in gamma synchrony as an underlying mechanism of SA also does not seem capable of explaining why this would lead to activations of specific voice representations.

Cho and Wu go on to say that “once we allow that a given episode of AVH involves the features of another person’s voice with its characteristic acoustic features, it is simple to explain why the patient misattributes the event to another person: that is what it sounds like” (p. 2). Taken to its extreme, this implies that any episode of inner speech that involves a voice other than one’s own would be experienced as “non-self”, and hence experienced as similar to an AVH, a proposition that would clearly not find much support in empirical research. Taking this view, it is the SA model that needs an additional mechanism to explain why neuronal representations of other people’s voices are experienced not just as sounding like someone else’s voice, but also having the non-self-generated, alien quality associated with AVHs. This is exactly the type of mechanism built into ISS models of AVHs.

Indeed, the authors do go on to argue that many problems with the inner speech model of AVHs can be solved if we stop referring to “inner speech”, and instead refer to “auditory imagination”, which, supposedly, is characterized by actual acoustical properties, unlike inner speech (the authors do not cite any literature to support this claim). We would argue that this falls within the realm of typical inner speech, and that the view put forward by Cho and Wu is based on unexamined assumptions about the typical form of inner speech. We would argue that a separate “type” of imagery is not needed, and it is probable that inner speech recruits at least some mechanisms of auditory imagery. Therefore, it does not make sense to argue that AVHs resemble one, but not the other.

Finally, it should be pointed out that auditory cortical regions are not the only areas reported to lead to AVHs when directly stimulated; for example, Bancaud et al. (12) reported that stimulating the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), an area often associated with error monitoring and cognitive control, caused auditory hallucinations, a finding that seems more compatible with self-monitoring accounts of AVH. Admittedly, it is possible that stimulation of ACC could have distal effects, also stimulating auditory cortical regions; we mention this finding simply to highlight the fact that the potential top–down effects of other brain regions on auditory cortical areas should not be overlooked.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

This research was supposed by a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award WT098455MA

References

1. Cho R, Wu W. (2013). Mechanisms of auditory verbal hallucination in schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry; 4:155. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00155 Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

2. Langdon R, Jones SR, Connaughton E, Fernyhough C. (2009). The phenomenology of inner speech: comparison of schizophrenia patients with auditory verbal hallucinations and healthy controls. Psychol Med; 39(4):655–63. doi:10.1017/S0033291708003978 Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

3. McCarthy-Jones SR, Fernyhough C. (2011) . The varieties of inner speech: links between quality of inner speech and psychopathological variables in a sample of young adults. Conscious Cogn; 20(4):1586–93. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2011.08.005 Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

4. Fernyhough C. (2004). Alien voices and inner dialogue: towards a developmental account of auditory verbal hallucinations. New Ideas Psychol; 22(1):49–68. doi:10.1016/j.newideapsych.2004.09.001 CrossRef Full Text

5. McCarthy-Jones SR. (2012). Hearing Voices: the Histories, Causes and Meanings of Auditory Verbal Hallucinations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

6. Jacobsen E. (1931). Electrical measurements of neuromuscular states during mental activities. VII. Imagination, recollection, and abstract thinking involving the speech musculature. Am J Physiol; 97:200–9.

7. Gould LN. (1948). Verbal hallucinations and activation of vocal musculature. Am J Psychiatry; 105:367–72.

8. McGuigan F. (1966). Covert oral behaviour and auditory hallucinations. Psychophysiology; 3:73–80. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.1966.tb02682.x CrossRef Full Text

9. Gould LN. (1950). Verbal hallucinations as automatic speech – the reactivation of dormant speech habit. Am J Psychiatry; 107(2):110–9.

10. Watkins KE, Strafella AP, Paus T. (2003). Seeing and hearing speech excites the motor system involved in speech production. Neuropsychologia; 41:989–994. doi:10.1016/S0028-3932(02)00316-0 Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

11. Bick P, Kinsbourne M. (1987). Auditory hallucinations and subvocalizations in schizophrenics. Am J Psychiatry; 14:222–5.

12. Bancaud J, Talairach J, Geier S, Bonis A, Trottier S, Manrique M. (1976). Manifestations comportementales induites par la stimulation electrique du gyrus cingulaire anterieur chez l’homme. Rev Neurol; 132:705–24.

Full Citation:

Moseley, P, and Wilkinson, S. (2014, Apr 22). Inner speech is not so simple: a commentary on Cho and Wu (2013). Frontiers in Psychiatry:Schizophrenia; 5:42. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00042

Mechanisms of Auditory Verbal Hallucination in Schizophrenia (Cho and Wu, 2013)

This is an interesting article on the occurrence of auditory hallucinations in psychosis/schizophrenia. It comes from the open access journal, Frontiers in Psychiatry: Schizophrenia. Later today or tomorrow I will post a commentary on this article, which is also quite interesting (if you care at all about this kind of stuff).

A LOT of people experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder from childhood trauma (or developmental trauma) experience verbal hallucinations. Quite often, the voices are those of the abusers. The voices are often extremely critical and demeaning. Less often, they tell the survivor they should be dead, or the should hurt themselves in very specific ways (command hallucinations, which are always a bad sign).

Very infrequently, and generally only in survivors of ritual abuse, the voices are experienced as demons or devils, or even as vicious animals who are supposed to kill the survivor.

NOTE: the sketch above is by "brokenwings101" at deviantART.

Full Citation:

Cho, R, and Wu, W. (2013., Nov 27). Mechanisms of auditory verbal hallucination in schizophrenia. Frontiers in Psychiatry: Schizophrenia; 4:155. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00155

Mechanisms of auditory verbal hallucination in schizophrenia

Raymond Cho [1,2] and Wayne Wu [3]

1. Center for Neural Basis of Cognition, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

2. Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

3. Center for Neural Basis of Cognition, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Recent work on the mechanisms underlying auditory verbal hallucination (AVH) has been heavily informed by self-monitoring accounts that postulate defects in an internal monitoring mechanism as the basis of AVH. A more neglected alternative is an account focusing on defects in auditory processing, namely a spontaneous activation account of auditory activity underlying AVH. Science is often aided by putting theories in competition. Accordingly, a discussion that systematically contrasts the two models of AVH can generate sharper questions that will lead to new avenues of investigation. In this paper, we provide such a theoretical discussion of the two models, drawing strong contrasts between them. We identify a set of challenges for the self-monitoring account and argue that the spontaneous activation account has much in favor of it and should be the default account. Our theoretical overview leads to new questions and issues regarding the explanation of AVH as a subjective phenomenon and its neural basis. Accordingly, we suggest a set of experimental strategies to dissect the underlying mechanisms of AVH in light of the two competing models.

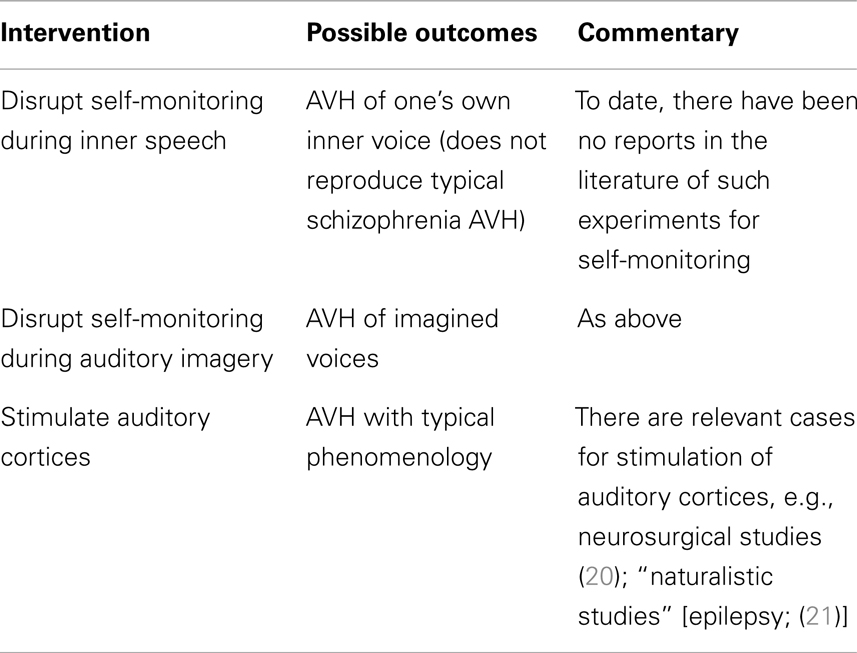

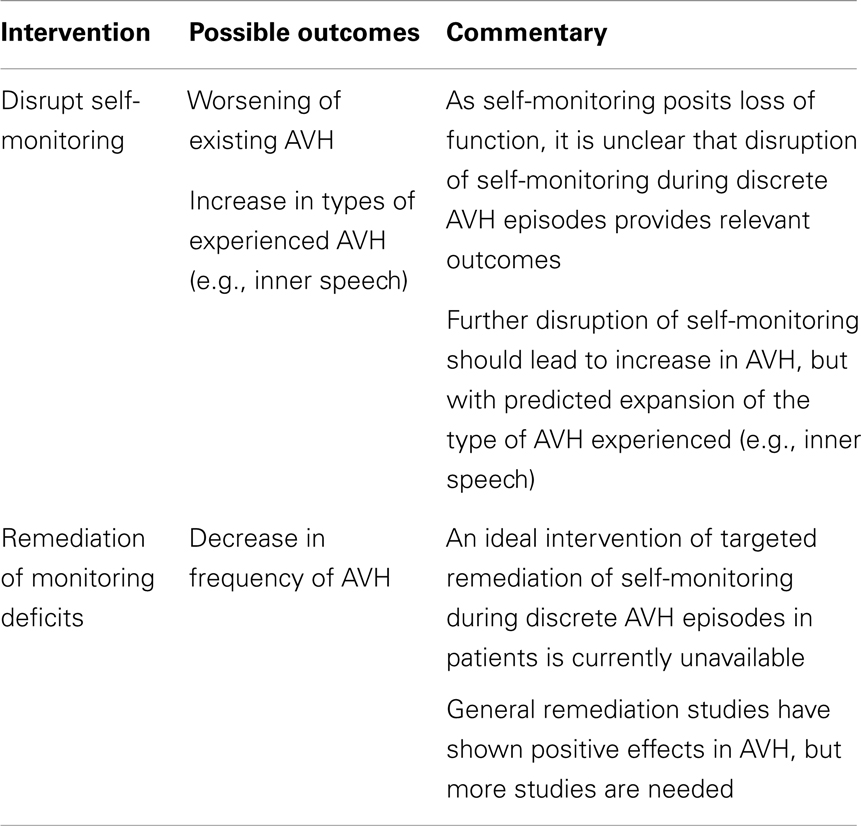

We shall contrast two proposed mechanisms of auditory verbal hallucinations (AVH): (a) the family of self-monitoring accounts and (b) a less discussed spontaneous activity account. On the former, a monitoring mechanism tracks whether internal episodes such as inner speech are self- or externally generated while on the latter, spontaneous auditory activity is the primary basis of AVH. In one sense, self-monitoring accounts emphasize “top-down” control mechanisms; spontaneous activity accounts emphasize “bottom-up” sensory mechanisms. The aim of this paper is not to provide a comprehensive literature review on AVH as there have been recent reviews (1, 2). Rather, we believe that it remains an open question what mechanisms underlie AVH in schizophrenia, and that by drawing clear contrasts between alternative models, we can identify experimental directions to explain what causes AVH. Self-monitoring accounts have provided much impetus to current theorizing about AVH, but one salient aspect of our discussion is to raise questions as to whether such accounts, as currently formulated, can adequately explain AVH. We believe that there are in fact significant limitations to the account that have largely gone unnoticed. Still, both models we consider might hold, and this requires further empirical investigation. Conceptual and logical analysis, however, will play an important role in aiding empirical work.

Logical and Conceptual Issues Regarding Mechanisms of AVH

What is AVH? It is important to be rigorous in identifying what we are trying to explain, especially since clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia depends on patients’ reports of the phenomenology of their experience. Yet even among non-clinical populations, the concepts we use to categorize experiences may be quite fuzzy and imprecise (3). While there is little controversy that AVH involves language (emphasis on “verbal”) we restrict our attention to auditory experiences, namely where AVH is phenomenally like hearing a voice. Just as cognitive scientists distinguish between perception and thought in normal experience, we should where possible distinguish between auditory hallucination and thought phenomena (e.g., thought insertion). Admittedly, categorizing a patient’s experience as auditory or thought can be difficult, but we should first aim to explain the clear cases, those with clear auditory phenomenology. Finally, by “hallucination” we take a simple view: in AVH, these involve internal (auditory) representations that a verbalized sound occurs when there is no such sound.

One of the prevailing standard models of AVH invokes self- (or source-) monitoring (see Figure 1). This covers a family of models that share a core idea: a defect in a system whose role is to monitor internal episodes as self-generated. There is good evidence that patients with schizophrenia show defective self-monitoring on a variety of measures (4), and this may explain some positive symptoms such as delusions of control. It remains an open question, however, whether this defect is the causal basis of AVH.

FIGURE 1We begin with proposals for the mental substrate of AVH: inner speech, auditory imagery, or auditory memory (5, 6). Most models take inner speech to be the substrate, but we think there are compelling phenomenological reasons against this (7, 8). Inner speech is generally in one’s own voice, is in the first-person point of view (“I”), and often lacks acoustical phenomenology (9). But even if there is controversy whether inner speech is auditory, there is no such controversy regarding AVH. As clinicians are aware, patients reflecting on the phenomenology of AVH typically report strong acoustical properties that are typically characteristic of hearing another person’s voice, where the voice typically speaks from a second- or third-personal point of view (“you” or “them” as opposed to “I”). Thus, what is typically represented in AVH experiences is starkly different from what is represented in normal inner speech experiences.

Figure 1. Depiction of the two causal mechanisms for the generation of auditory verbal hallucination (AVH). The self-monitoring model is more complex than the spontaneous activity account.

This point on phenomenological grounds indicates that a self-monitoring model that identifies inner speech as the substrate for AVH incurs an additional explanatory burden. It must provide a further mechanism that transforms the experience of the subject’s own inner voice, in the first-person and often lacking acoustical properties such as pitch, timbre, and intensity into the experience of someone else’s voice, in the second- or third-person, with acoustical properties. For example, how does inner speech in one’s own voice with its characteristic features become an AVH of, for example, the neighbor’s voice with its characteristic features? To point out that a patient mistakenly attributes the source of his own inner speech to the neighbor does not explain the phenomenological transformation. Indeed, once we allow that a given episode of AVH involves the features of another person’s voice with its characteristic acoustic features, it is simple to explain why the patient misattributes the event to another person: that is what it sounds like. Indeed, a phenomenological study found that in addition to being quite adept at differentiating AVH from everyday thoughts, patients found that the identification of the voices as another person’s voice was a critical perceptual feature that helped in differentiating the voices from thought (10). The point then is that inner speech models of AVH are more complex, requiring an additional mechanism to explain the distinct phenomenology of AVH vs. inner speech.

On grounds of simplicity, we suggest that self-monitoring accounts should endorse auditory imagination of another person’s voice as the substrate of AVH. If they do this, they obviate a need for the additional transformation step since the imagery substrate will already have the requisite phenomenal properties. Auditory imagination is characterized by acoustical phenomenology that is in many respects like hearing a voice: it represents another’s voice with its characteristic acoustical properties. Thus, our patient may auditorily imagine the neighbor’s voice saying certain negative things, and this leads to a hallucination when the subject loses track of this episode as self-generated. On this model, there is then no need for a mechanism that transforms inner speech phenomenology to AVH phenomenology. Only the failure of self-monitoring is required, a simpler mechanism. In this case, failure of self-monitoring might be causally sufficient for AVH. We shall take these imagination-based self-monitoring models as our stalking horse.

But what is the proposed “self-tagging” mechanism? We think self-monitoring theorists need more concrete mechanistic proposals here. The most detailed answer invokes corollary discharge, mostly in the context of forward models (11–13). This answer has the advantage that it goes beyond metaphors, and we have made much progress in understanding the neurobiology of the corollary discharge signal and forward modeling [see Ref. (14) for review]. These ideas have an ancestor in von Helmholtz’s explanation of position constancy in vision in the face of eye movements: why objects appear to remain stable in position even though our eyes are constantly moving. Position constancy is sometimes characterized as the visual system’s distinguishing between self- and other-induced retinal changes, and this is suggestive toward what goes wrong in AVH.

Forward models, and more generally predictive models, build on a corollary discharge signal and have been widely used in the motor control literature [see Ref. (15) for review; for relevant circuitry in primates controlling eye movement, see Ref. (16)]. The basic model has also been extended to schizophrenia (11–13), and a crucial idea is that the forward model makes a sensory prediction that can then suppress or cancel the sensory reafference. When the prediction is accurate, then sensory reafference is suppressed or canceled, and the system can be said to recognize that the episode was internally rather than externally generated.

There are, in fact, many details that must be filled in for this motor control model to explain AVH, but that is a job for the self-monitoring theorist. Rather, we think that failure of self-monitoring, understood via forward models, is still not sufficient for AVH, even with auditory imagination as the substrate. The reason is that there is nothing in the cancelation or suppression of reafference – essentially an error signal – that on its own says anything about whether the sensory input is self- or other-generated. Put simply: a zero error signal is not the same as a signal indicating self -generation, nor is a positive error signal the same as a signal indicating other-generation. After all, the computation of prediction error is used in other systems that have nothing to do with AVH, say movement control. Thus, while an error signal can be part of the basis of AVH, it is not on its own sufficient for it. Given the failure of sufficiency of self-monitoring models on their own to explain AVH, we believe that an additional mechanism beyond failure of self-monitoring will always be required to explain AVH. Specifically, the required mechanism, an interpreter, is one that explains the difference between self and other. The challenge for proponents of the account is to specify the nature of this additional mechanism [e.g., (17)]. As Figure 1 shows, the mechanism for AVH on self-monitoring accounts is quite complex.

We now turn to an alternative that provides a simple causally sufficient condition for AVH: AVH arise from spontaneous activity in auditory and related memory areas. We shall refer to this account as the spontaneous activity account [for similar proposals, see Ref. (2, 18, 19)]. The relevant substrates are the activation of specific auditory representation of voices, whether in imagination or memory recall (for ease of expression in what follows, we shall speak of activity in auditory areas to cover both sensory and relevant auditory memory regions, specifically the activation of representations of the voice that the subject typically experiences in AVH). We think that this should be the default account of AVH for the following reason: we know that appropriate stimulation of auditory and/or relevant memory areas is sufficient for AVH. Wilder Penfield provided such a proof of concept experiment.

Penfield and Perot (20) showed dramatically that stimulation along the temporal lobe resulted in quite complex auditory hallucinations. For instance, stimulations along the superior temporal gyrus elicited AVH with phenomenology typical of schizophrenia AVH, as noted in his case reports: “They sounded like a bunch of women talking together.” (622 p.); or more indistinct AVH – “Just like someone whispering, or something, in my left ear” or “a man’s voice, I could not understand what he said” (640 p.). Activity in these areas, spontaneously or induced, in the absence of an actual auditory input are cases of auditory hallucination: auditory experience of external sounds that do not in fact exist. The clinical entity epilepsy provides a similar, more naturalistic example of spontaneous cortical activity giving rise to AVH, in addition to a wide variety of other positive symptoms (21). The hypothesis of spontaneous activity is that AVH in schizophrenia derives from spontaneous auditory activation of auditory representations.

The basic idea of the spontaneous activity account is that the auditory system, broadly construed, encodes representations of previously heard voices and their acoustical properties. In the case of normal audition, some of these representations are also activated by actual voices in the environment, leading ultimately to auditory experiences that represent those voices. The idea of hallucination then is that these representations can be spontaneously activated in the absence of environmental sounds. Thus, the initiation of an episode of AVH is driven by spontaneous activation. Certainly, as in many cases of AVH, the experience can be temporally extended. This might result from some top-down influences such as the subject’s attention to the voice, which can further activate the relevant regions, leading to an extended hallucination. Indeed, there are reported cases of patients answering the AVH with inner speech in a dialog [12 of 29 patients in Ref. (9)]. Further, that top-down processes are abnormally engaged by bottom-up influences is suggested by the finding that there is a disturbance in connectivity from the superior temporal gyrus (sensory region) to the anterior cingulate cortex (involved in cognitive control) with AVH compared to patients without AVH and healthy controls (22). This raises two points: (1) that an inner speech response could induce additional activation of auditory representations and (2) that self-monitoring models that take inner speech as the AVH substrate are quite implausible here since the monitoring mechanism must go on and off precisely with the AVH and inner speech exchange.

Since the auditory representations spontaneously activated already encode a distinct person’s voice and its acoustical properties, there is no need for a system to interpret the voice represented as belonging to another person (recall the issue regarding inner speech above). That information about “otherness” is already encoded in the representation of another’s voice. In this way, the spontaneous activity account bypasses the complex machinery invoked in self-monitoring. On its face, then, the spontaneous activity account identifies a plausible sufficient causal condition for AVH that is much simpler than self-monitoring mechanisms. There are, of course, details to be filled in, but our point is to contrast two possible mechanisms: self-monitoring and spontaneous activity. We hope, at least, to have provided some initial reasons why the latter might be more compelling.

When a field is faced with two contrasting models, it must undertake specific experiments to see which may hold. Before we delve into concrete experimental proposals, we want to highlight some remaining conceptual points. First, the models are not contradictory, and thus both could be true. We might discover that across patients with AVH or across AVH episodes within a single patient, AVH divides between the two mechanisms. Second, both models make some similar predictions, namely that in AVH, we should see the absence of appropriate self-monitoring in an AVH episode, though for different reasons. On the self-monitoring account, this absence is due to a defect in the self-monitoring system; on the spontaneous activity account, this absence is due to spontaneous activity that bypasses self-monitoring. Critically, empirical evidence that demonstrates absence of appropriate self-monitoring during AVH does not support the self-monitoring account as against the spontaneous activity account. We need different experiments.

Finally, the spontaneous activity account is more parsimonious as seen in Figure 1, but is this really an advantage? Note that all accounts of AVH must explain (a) the spontaneity of AVH episodes (they often just happen) and (b) the specificity of phenomenology in AVH, namely negative content, second or third-person perspective, and a specific voice, identity and gender, etc. Both accounts can deal with the spontaneity: in self-monitoring, it is explained by spontaneous failure of self-monitoring so that AVH feels spontaneous; in the spontaneous activity account, it is the actual spontaneous activity of auditory areas.