Michael Ungar, PhD, is a family therapist and a professor of social work at Dalhousie University, where he codirects the Resilience Research Centre. He’s the author of Too Safe for Their Own Good: How Risk and Responsibility Help Teens Thrive.

This article was published originally in Psychotherapy Networker magazine and re-posted at Alternet.

This style of parenting seems to weird to me. Granted, I grew up in the 1970s, in a quiet suburb of Los Angeles, but I had an incredible amount of freedom compared to today's kids. As a seven or eight year old (maybe younger), I was allowed to walk nearly a mile to the 7-11 to buy baseball cards with my allowance on a Saturday morning. At eight or nine, I could ride my bicycle several miles with a friend or two to go to Magic Mountain, which included crossing several major intersections. As a nine-year-old in southern Oregon, I was allowed to be out all day, fishing my way with a friend down Williams Creek.

I grew up with the freedom to make mistakes, get stuffed in a garbage can (I was six, and we were riding our bikes in the junior high school down the street), and to explore the world in which I grew up. Those experiences are part of who I am today.

Psychologist: Stop Bubble-Wrapping Your Kids! How Overprotection Leads to Psychological Damage

If overprotection can disadvantage children, why do so many parents continue to bubble-wrap their kids?

Psychotherapy Networker / By Michael Ungar

September 17, 2014 | I’m sure Shyam wasn’t thinking about the harm she was causing her 8-year-old daughter, Marian, when she demanded her daughter’s school put an extra crossing guard closer to their home. Nor did she doubt herself when she insisted that children be barred from bringing oranges to school because Marian developed a minor rash every time she ate one. At home, Marian was closely monitored and never allowed to take risks: no sleepovers, no playing on the trampoline with friends, no walking to the corner store (less than a block away) by herself.

Shyam might sound extreme in her parenting, but among the families that come to therapy these days, she’s far from an outlier. While not all overprotective parents are as extreme in their behaviors as Shyam (indeed, few experience themselves as being obsessive at all), many middle-class families are struggling to decide how much protection is the right amount, even when their children are showing signs of anxiety and rebellion as a result. Whether these families are my clients or my neighbors, overprotective parenting appears to have become the rule, rather than the exception, in today’s world.

I’ll be the first to admit that I found it difficult not to roll my eyes and tell Shyam to lighten up. I wanted to share stories about my own upbringing, which included healthy doses of benign neglect by a mother who told me to go outside and play and not come back until I was hungry, or badly injured.

Or I could’ve explained to Shyam that there’s now consensus among social scientists that children across the United States, Canada, Australia, England, and other high-income countries have never been safer. Even the respected epidemiologists at the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta recently published a report that showed that the real risks to our children aren’t abductions by strangers or being murdered, but much more commonplace problems like bullying and obesity. Believe it or not, physical fighting, cigarette use, and even sexual activity among teens are all decreasing. And the police chiefs of Canada, much like police chiefs in other countries, tell us that crime in our communities is down, and that the person most likely to assault a child sexually is still, by far, a member of the child’s own family.

In my experience, however, no amount of statistical reporting gets parents to stop hovering over their children. Regardless of whether the parent is seeing me clinically or we’re sharing a burger on my back deck, statistics do not change behavior. The patterns are too enmeshed—and worse, reinforced by neighbors (who criticize parents for letting 8-year-olds walk to school alone), educators (who’ve forbidden failure in the classrooms and sanitized playgrounds), and Fox News anchors (who sensationalize every child abduction, no matter where it’s taken place). Shyam is symptomatic of a new normal, which is causing real harm to children’s psychosocial development.

This new normal is a growing pattern of overprotection that I’ve seen emerging as one of the thorniest clinical issues for therapists because it can look so reasonable. If we therapists have children too (I have two older teens), we may find ourselves empathizing and afraid to admit that we’re just as crazy when it comes to our own kids. Statistics be damned! We’re not going to let anything bad happen to our child.

Where Shyam is a little different from other parents is that, as a consequence of her relentless efforts to protect her daughter and ensure her success at every activity, Marian began to experience severe anxiety before school each day and show the early signs of anorexia. Indeed, the growing number of young adults who aren’t allowed responsibilities in life and who are presenting with anxiety disorders is a warning sign that many parents have lost their way. As a consultant to Shyam’s case, I knew that her fears needed to be challenged, albeit gently, and that Marian needed much more control over the decisions that affected her. The question was how could we, as the family’s clinical team, help Shyam and Marian find a new normal.The Risk-Taker’s Advantage

Over years of working with parents to help undo the bubble wrap around their children, I’ve found four questions to be useful. Rather than insisting that parents change their behavior and supervise their children less, or trying to persuade them that the world really is a safer place today, I focus on how they can give their kids opportunities to experience the manageable amounts of risk and responsibility needed for success. I ask them:

1. When you were growing up and were about the same age as your child, what risks did you take and what responsibilities did you have?These questions, especially the fourth one, shift the focus of the clinical work from trying to get parents to stop overprotecting to doing what’s positive for their children, which is providing them with opportunities to experience what I call the risk-taker’s advantage.

2. What did you learn from those experiences?

3. Later in life, how helpful were those lessons?

4. How will your child learn the same life lessons?

That advantage comes when children are given the chance to experience just enough stress to demand their full attention, but not so much that it overwhelms them. These manageable experiences can come in two forms—taking risks and assuming responsibility—which often go hand in hand. For example, giving a child her first pocket knife at, say, age 9 not only gives her the advantage of experiencing a little risky play with a sharp object: it signals that she’s responsible for keeping herself and others safe. Of course, few families find it difficult to argue against giving a child her own pocketknife, but ask those same parents to let their 9-year-old ride her bike to school alone, use the stove to help cook dinner, or go into a fast-food restaurant and order her meal by herself, and suddenly you’ll see them unsure about whether their child is competent enough to keep herself safe or responsible enough to make good decisions.

When we bubble-wrap children, we deny them opportunities to experience what evolutionary psychologists have described as antiphobic play. “Free-range children,” a term coined by New York City journalist Lenore Skenazy, are likelier to experience the exhilaration of overcoming situations that they’re biologically hardwired to fear until they have the physical and psychological maturity to cope with them. Riding the subway at age 9 alone and climbing high up into a tree both offer children the same opportunity to experience enough risk to scare themselves a bit while feeling responsible for the consequences that can follow recklessness. Adventurous play and progressively larger responsibilities are important building blocks for psychological well-being.

Shyam may have given Marian the protection an 8-year-old sometimes requires, but she was neglecting her daughter’s need to encounter risk, like going to the playground with her friends and attending sleepovers at someone else’s house, where bedtimes and expectations may differ from those at home. Such experiences bring with them advantages we can’t provide our kids without help from others.

When I met with Shyam alone, I used the four questions to tease apart her beliefs about her role as a parent and what Marian needed psychologically. When I asked Shyam what risks she’d taken growing up, she told me about her strict upbringing, in which she’d made few, if any, decisions on her own. She was expected to share responsibilities for housework and looking after her younger siblings. She was rarely outside her parents’ supervision—at least until college, when she went through a period of rebellion, tried drinking, and even had a boyfriend, though she refused to be sexually active until she married her husband, whom she met shortly after graduation.

Shyam’s early years had made her feel secure at home, but she’d learned little about taking chances outside it. She didn’t, at first, want to acknowledge that this pattern could be a problem for Marian. Her daughter would, she insisted, be a success, someone her whole family (including the grandparents) would admire. Nothing could put that success at risk.

I next asked Shyam whether she’d learned anything from having so many responsibilities as a child, or if taking those risks in college had taught her anything that was useful later in life. She admitted she was a little bitter about the responsibilities she’d been given, but happy that her childhood had taught her how to look after others. Her behavior at college, however, was unforgivable, she said, insisting nothing good had come of any of it.

“So let me see if I’m understanding,” I said to Shyam. “All those responsibilities you had while younger were good, even though you didn’t always like them?”

“What I liked was that I felt a lot older, ready to have my own children,” she responded.

“I sometimes hear from children who take risks that they feel much the same afterward. Both experiences—of taking risks and having responsibilities—make us feel older,” I said, “or in control of our lives. So I’m wondering, if you became a responsible adult by having responsibility for others, how is Marian going to find that same feeling of being all grown up?”

“I don’t want her to have to give up her childhood like I did,” Shyam protested.

“Yes, I understand,” I said. “But then, if she has no responsibilities for herself or others, and she’s not taking many risks, how will she learn the life lessons she needs to get ready to be away at college when she’s older?”

Though Shyam hesitated to admit it, I had the sense that my questions were making her worry that Marian would be less prepared for adulthood than even she had been. “I don’t know what else to do. She’s just a child, and our community is so dangerous,” she argued.

I knew Shyam was stuck, unsure of what else she should do. Pulling out the “our community is so dangerous” card was a last-ditch effort to defend herself and keep doing more of what she felt comfortable doing. For better or worse, though, Marian’s anxiety was increasing, and Shyam realized she couldn’t stop it by accompanying Marian to school each morning and sitting beside her for the first hour. Exasperated, Shyam finally began to look cautiously for opportunities to give Marian more risks and responsibilities appropriate to her age. She began by leaving Marian alone at her gymnastics lesson and letting her coach decide what amount of safety equipment was necessary. As Shyam explained, justifying her decision to us both, “She’s a professional coach and former national champion. I think she can assess the danger to Marian better than me, right? But I can’t watch. I have to go and come back or else I just get in the way.”

It was a helpful first step that let Marian experience both a measure of well-managed risk and a period of responsibility for herself. When I asked Marian about the change, she was enthusiastic about the independence she was experiencing. Gymnastics lessons without her mother may have seemed to me like just a normal kid activity—but to Marian, it may as well have been a solo flight over Antarctica.

Unfortunately, however, even when parents try to stop hovering over their child, the social gaze of their extended families and communities can thwart their efforts. One mother I met was surprised when her neighbor knocked on her door holding the mother’s 5-year-old son by the hand. “I saw him playing at the bottom of your driveway and thought you should know he was near the road,” she said.

“Thank you,” the mother replied and explained that she’d taught her son not to go off the driveway. Besides, even if he had, she’d reasoned, the traffic on their quiet suburban street was so light, it was unlikely the boy would have been hurt.

“Oh, he hadn’t gone in the road at all,” said the neighbor. “But it just looked to me like he could be in some danger.”

All this emphasis on safety and monitoring our children is missing the point of parenting. While children are young enough to pay attention to the advice of their caregivers, they should be encouraged to experience enough risk and responsibility to learn from the small mistakes they’re bound to make.

Kids Need Responsibility

When 13-year-old Tricia came to see me she was doing everything she could to distance herself from a world of zero risk and predictable success. Just months before I met her, she’d been the preppy kid with the big smile and enthusiasm for fundraising. Then puberty whooshed in like a thunderstorm and she began asking for more risk and more responsibility, like being able to stay out later with her friends. It was normal kid stuff, which a generation or two ago would never have triggered a referral to therapy. However, Tricia’s parents, like most other parents in their community, were suddenly becoming overprotective. Instead of realizing their daughter was growing up and looking for the rites of passage that mark a transition to adulthood, they’d begun to worry that she was in too much danger beyond their front door.

Like any high-spirited youth, Tricia rebelled. She turned Goth, dyed her hair black, and began disappearing after school. Her rebelliousness led to arguments at home and groundings. These only made matters worse. By the time I caught up with Tricia and her parents, Tricia had fully committed herself to doing everything in her power to show them that she could look after herself. Unfortunately, that had meant experimenting with soft drugs and alcohol and finding a boyfriend a couple years older than her. It might sound extreme, but in my experience such behaviors have become common among the middle-class kids from secure homes with caregivers who put too much effort into monitoring them. Tricia didn’t want to be “bad,” but what other choice did she have if she was going to experience enough risk and responsibility to feel grown up?

Over several weekly meetings, I invited Tricia’s parents to talk about their lives growing up, with their daughter present. Those conversations became the basis for renegotiations of the house rules and discussions about how to assign Tricia meaningful responsibilities at home. In other words, we stopped the arguments over making her bed and instead insisted she help shop for the weekly groceries and cook once a week. We also worked on getting Tricia’s parents to stop saying no and instead find ways to say yes to the developmental things Tricia wanted to take on. That meant allowing her to have a boyfriend, but insisting she sit down with their family doctor to discuss sexual health and safety. Tricia’s father summarized our work together this way: “I guess if she’s old enough to mess up, she’s old enough to take some responsibility to do things right.”

It was interesting that as Tricia was given more opportunities to experience manageable amounts of risk and responsibility for herself and others, she began to appreciate the structure her parents were providing. She came home for dinner more often, didn’t mind being reminded to go to bed when it was getting late on a school night, and even agreed to go on a family camping trip. She was, after all, still a child, with a child’s need for attachment to her caregivers, but she was also an adolescent, who required experiences beyond those that her family could provide her.

A Solution to Overprotection

I recently spoke to an audience of 500 teachers and caregivers about the potential consequences of overprotective parenting. If the questions afterward indicated anything, it’s that as a group, we’re split on what makes for good parenting at a time when we perceive our children threatened by everything from pedophiles to peanuts.

One mother wanted to know if it would be appropriate for her 7-year-old son to walk to school on his own (she’d been letting him do it, but worried that other parents considered her irresponsible). Rather than answering yes or no, I suggested she consider whether there were major highways to cross or gangs of violent youth waiting to rob her son. I asked her about her child’s ability to find his way alone. And then I asked her how she’d gotten to school when she’d been 7. As she considered each question, I could see her reaching the same conclusion I’d have reached: that if her community is as safe as most middle-class neighborhoods, then yes, her child should walk to school.

The next parent asked how to handle his 12-year-old daughter, who wanted to get a tattoo. He wished she’d wait, but wondered if he was just being overprotective. The issue had become an ongoing struggle, and the girl was threatening to run away if her parents didn’t let her do what she wanted. Before answering, I had to take a deep breath, anxious that the audience understand that not being overprotective wasn’t the same as being too permissive.

“I’m not sure a 12-year-old can make a well-informed decision about a tattoo,” I said. “That seems to be something we as parents should exercise some control over. If she were my daughter, I’d tell her to wait, at least until she likes wearing the same style of clothing for more than a year.” The audience laughed. “Could you give her a clothing allowance instead and let her choose what she wears for a few years, and then promise to revisit tattoos when, say, she’s 16?”

The audience’s questions highlighted the problem we face as parents. We’ve become so focused on keeping children safe that many of us don’t seem to know what’s normal anymore. It’s as if we look at children as a species of underevolved pets, whom we adults must take care of. Excessive protection, however, goes against what we know about the positive role that risk and responsibility play in children’s development.

Being pushed to the point of failure at tasks that, with effort, we can manage is necessary to develop a sense of personal efficacy. Research on children’s behavior in sports shows that children who have incremental opportunities to push themselves to the limits of their ability are likelier to handle genuinely daunting physical challenges, like a double black-diamond ski run, with aplomb because of the confidence they gain by facing and surmounting challenges. Untested children are likelier to be anxious, tense, afraid of the hill, and therefore the odds-on favorites to wind up in a cast.

I’ve found in my clinical work that the solution to the problem of overprotection can begin with two tasks. First, parents need to make a realistic survey of the risks their children face at home and beyond their front door. Second, they need to assess their children’s capacity to solve their own problems given the risks they face. If we remember that resilience is nurtured when children have the support they need to develop competencies and self-efficacy, then our role as caregivers (and therapists) becomes that of crossing guards, rather than jailors. We can ease children’s successful—if sometimes challenging—transition through danger, rather than sparing them from danger altogether.

Enabling Change

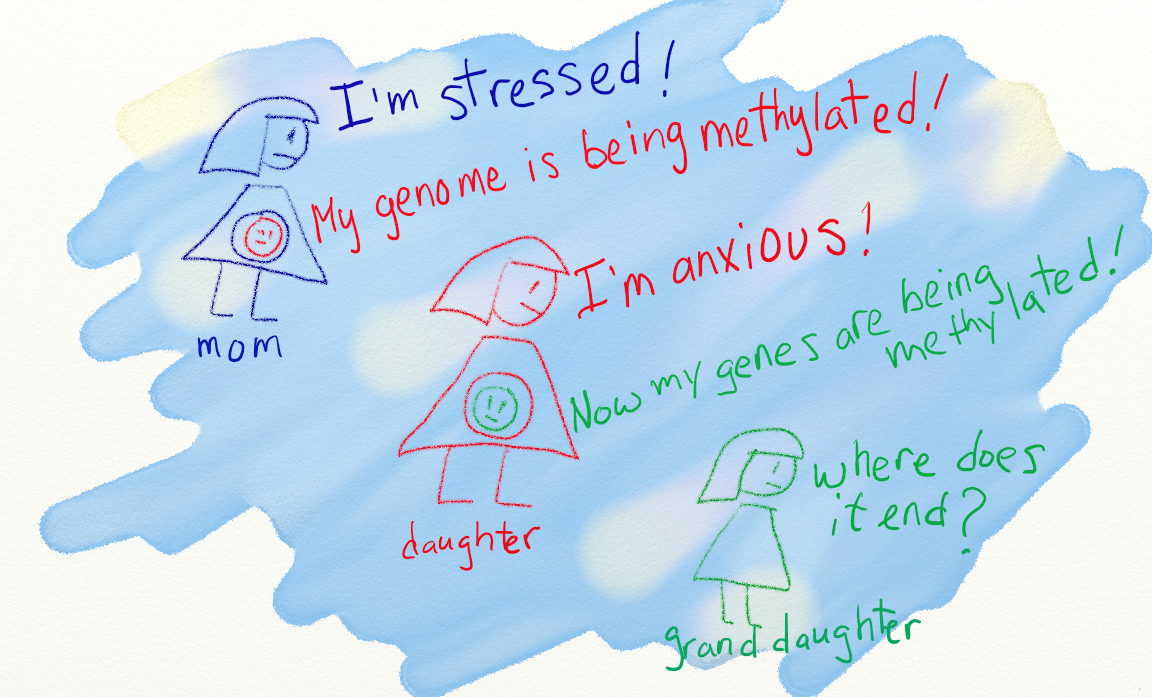

A great deal of neurological evidence shows that facilitated engagement with a mildly stressful environment may be beneficial to a child’s development. Bruce Ellis at the University of Arizona and W. Thomas Boyce at the University of British Columbia have worked together to show that a highly emotionally reactive child (made that way by genetic predisposition or obsessive parenting) can function just fine in a low-stress and well-supported household, but wilts when put into new surroundings. Of course, that doesn’t mean we want to force children to endure rocky lives just to develop a hardy disposition. The best environments for children foster growth, but they don’t overwhelm them with so much shelter that children lack opportunities to develop the skills they’ll need to survive when bad things happen.

I hate blaming parents for messing up their kids, but the truth is that many parents today aren’t doing what they should be doing to ensure their children’s optimal development. We’re seeing an explosion of cases in which love and protection are trumping common sense and science. For example, the therapist of an overly anxious 7-year-old consulted with me because he knew the boy’s anxiety was being triggered by his mother, who constantly reminded him of how dangerous school can be and of his own fragility. Germs are everywhere, the mother told him, so he should always carry a bottle of hand sanitizer and never play in the sandbox. Playground equipment can break bones, so he should never play on the swings or, heaven forbid, the teeter-totter. Strangers are lurking to steal the child in every grocery store, so he must never be out of eye contact with her. As if all that wasn’t bad enough, the boy was expected to succeed at every task, from playing nicely with his friends to reading three grade levels beyond his age. Unsurprisingly, he became insecure and shy whenever his mother left him. He refused to go outside at recess unless an adult accompanied him. In class, if he couldn’t solve a math problem or his drawing wasn’t beautiful enough, he’d throw a tantrum.

We tried asking the boy’s mother to focus less on germs and more on encouraging her son to become healthy and strong by spending time outside. We asked her about her favorite sports growing up (she couldn’t recall any), and we asked her to research the real risks to her child from germs. Despite repeated efforts to have her reconsider what she said to her son, there was little measurable change after several months. It was as if we couldn’t find a way to help her without making her more defensive.

Eventually, we reached out to the boy’s school and his paternal grandfather for whatever help they could offer. The school agreed to give the boy some responsibility, encouraging him to help teach the younger children to read. His grandfather agreed to take the boy out once a week for an adventure: a waterpark, four-wheeling at a nearby farm, or just staying out late enough to watch the fireworks on the Fourth of July. It was difficult to get the mother to agree to these interventions, as small as they were, but since they were being offered by trusted sources of support, they were easier to sell. Finally, we spoke with the boy about his experience of the world and whether he found it dangerous. The more opportunities he had for interesting excursions and assisting the teacher, the more he began to like being with other people. He began making new friends and even stopped refusing to go out at recess.

Since the boy’s mother never really changed, we enlisted the help of external partners to do what she couldn’t bring herself to do: expose her son to risk and responsibility. As a systemic therapist, I sometimes feel strange benching parents to give their children what they need developmentally. But in many cases when anxiety or delinquency reflects overly enmeshed and overly protective parenting, I’ve found that the solutions need to be more ecological. In other words, it’s a matter of changing the environment—which can mean giving kids chances to use an ax when camping, or ride a snowmobile. Even the most vulnerable kids will grow if the environment is rich in opportunities.

The Problems of the Privileged

The pattern of overmonitoring children’s every move and emotional experience shows up in dozens of ways, small and large. Think, for example, of parents who sit and watch their 5-year-old at a soccer practice, the team swarming the ball as it moves from one end of the field to the other. It does a child no good when every time she touches the ball, her parents shout, “Way to go!” and clap enthusiastically. The child has done nothing to merit such praise and, in my experience, can grow up expecting to be the darling of everyone’s attention all the time. That’s not the perfect formula for the kind of individual who can form an equal and loving relationship with another person. According to these kids’ parents, though, nothing should threaten their children’s self-esteem. While these parents mean well, the world of hand sanitizers, net nannies, and oversupervision isn’t giving children the risk-taker’s advantage.

As a therapist, I encounter children when overprotection has led to psychopathology. My role is to remind parents, gently but firmly, that their children need a variety of experiences for normal development, including opportunities to screw up and fix their problems themselves. The work can be exhausting, if only because this always seems like it’s a problem we don’t need to be having. I understand better the need for intervention with children coping with exposure to war, racism, and bullying. But being overprotected in safe communities, with lots of advantages in life? It makes no sense, but it’s a problem of the privileged that doesn’t appear to be going away anytime soon.

Sometimes I succeed in helping families reconsider their obsession with their child’s success and safety; sometimes not so much. What I do know is that often when I’m successful as a therapist, parents who were once overprotective zealots, doing what they’d been told by risk-averse communities, become allies in the battle to change their children’s schools and neighborhoods. They’re the ones pushing for zip lines on the playground, permission for children to throw snowballs during recess, and organizing bike-to-school days.

If overprotection can disadvantage children, why do so many parents continue to bubble-wrap their kids? Should we blame a culture of risk aversion, or the news media’s obsession with sexual assaults on children? Do some parents like to keep their children endlessly dependent? Or do they have such fragile egos that they need their children to be safe and successful so they can feel whole? Individual families offer many reasons for patterns of overprotection that may pose challenges in therapy. What’s clear to me is that parents, whatever their motives, don’t give up patterns of overprotection just because the statistics tell them their communities are safe. Most parents, however, will change when they’re persuaded that they’re disadvantaging their child. After all, they’re fundamentally motivated to see their child succeed. Once they recognize that a mix of a little failure, a lot of responsibility, and some risk can help their child become healthier and happier, they begin to see their children and their role as parents with new eyes. Suddenly, being a good parent no longer seems irreconcilable with learning to lighten up.