Steve Fleming, whose blog is The Elusive Self, offers a review/overview of a new theory of consciousness, as outlined by Michael Graziano in his 2013 book, Consciousness and the Social Brain.

I happen to have this book, but I have not gotten around to reading it. In the front matter of the book there is a brief overview of the theory.

SPECULATIVE EVOLUTIONARY TIMELINE OF CONSCIOUSNESSThis article does a good job of explaining the theory, and in essence, reviewing the book.

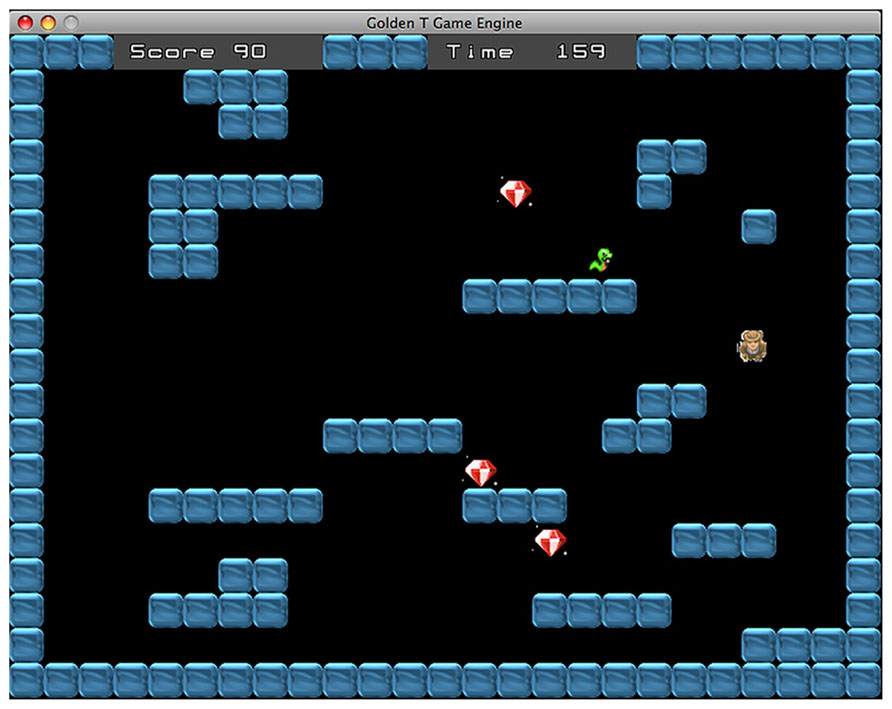

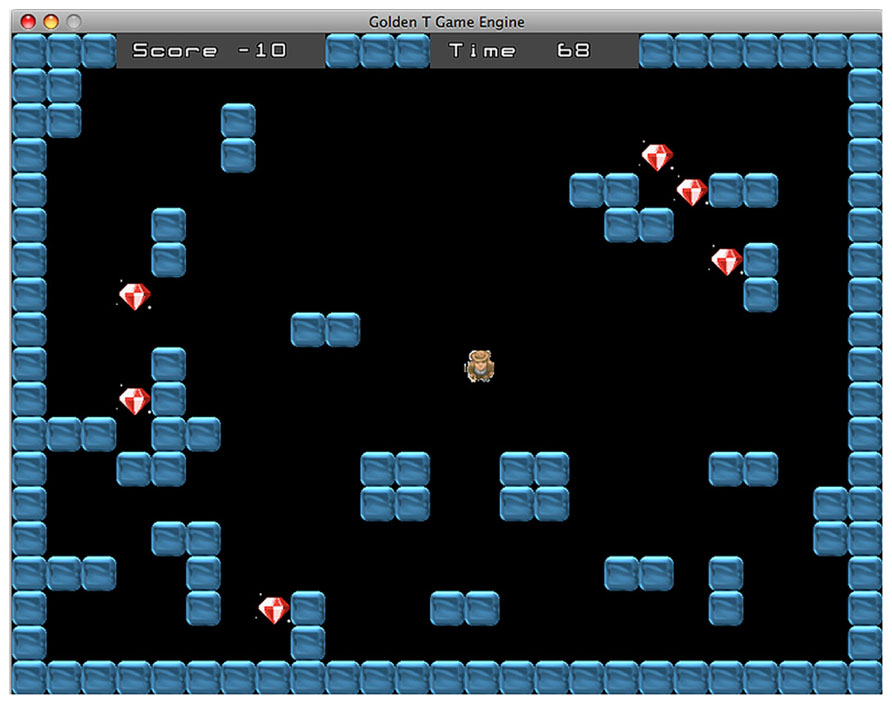

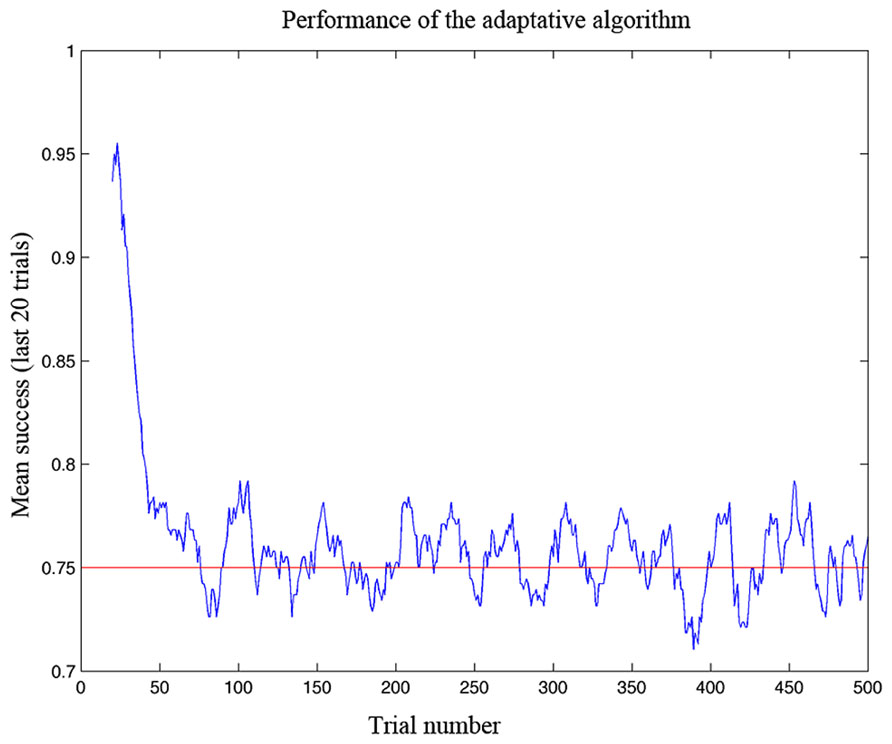

The theory at a glance: from selective signal enhancement to consciousness. About half a billion years ago, nervous systems evolved an ability to enhance the most pressing of incoming signals. Gradually, this attentional focus came under top-down control. To effectively predict and deploy its own attentional focus, the brain needed a constantly updated simulation of attention. This model of attention was schematic and lacking in detail. Instead of attributing a complex neuronal machinery to the self, the model attributed to the self an experience of X—the property of being conscious of something. Just as the brain could direct attention to external signals or to internal signals, that model of attention could attribute to the self a consciousness of external events or of internal events. As that model increased in sophistication, it came to be used not only to guide one’s own attention, but for a variety of other purposes including understanding other beings. Now, in humans, consciousness is a key part of what makes us socially capable. In this theory, consciousness emerged first with a specific function related to the control of attention and continues to evolve and expand its cognitive role. The theory explains why a brain attributes the property of consciousness to itself, and why we humans are so prone to attribute consciousness to the people and objects around us.

Timeline: Hydras evolve approximately 550 million years ago (MYA) with no selective signal enhancement; animals that do show selective signal enhancement diverge from each other approximately 530 MYA; animals that show sophisticated top-down control of attention diverge from each other approximately 350 MYA; primates first appear approximately 65 MYA; hominids appear approximately 6 MYA; Homo sapiens appear approximately 0.2 MYA

A theory of consciousness worth attending to

Steve Fleming | The Elusive Self

Oct 12, 2014

There are multiple theories of how the brain produces conscious awareness. We have moved beyond the stage of intuitions and armchair ideas: current debates focus on hard empirical evidence to adjudicate between different models of consciousness. But the science is still very young, and there is a sense that more ideas are needed. At the recent Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness* meeting in Brisbane my friend and colleague Aaron Schurger told me about a new theory from Princeton neuroscientist Michael Graziano, outlined in his book Consciousness and the Social Brain. Aaron had recently reviewed Graziano’s book for Science, and was enthusiastic about it being a truly different theory – consciousness really explained.

I have just finished reading the book, and agree that it is a novel and insightful theory. As with all good theories, it has a “why didn’t I think of that before!” quality to it. It is a plausible sketch, rather than a detailed model. But it is a testable theory and one that may turn out to be broadly correct.

When constructing a theory of consciousness we can start from different premises. “Information integration” theory begins with axioms of what consciousness is like (private, rich) in order to build up the theory from the inside. In contrast, “global workspace” theory starts with the behavioural data – the “reportability” of conscious experience – and attempts to explain the presence or absence of reports of awareness. Each theory has different starting points but ultimately aims to explain the same underlying phenomenon (similar to physicists starting either with the very large – planets – or the very small – atoms, and yet ultimately aiming for a unified model of matter).

Dennett’s 1991 book Consciousness Explained took the reportability approach to its logical conclusion. Dennett proposed that once we account for the various behaviours associated with consciousness – the subjective reports – there is nothing left to explain. There is nothing “extra” that underpins first-person subjective experience (contrast this with the “hard problem” view: there is something to be explained that cannot be solved within the standard cognitive model, which is exactly why it’s a hard problem). I read Dennett’s book as an undergraduate and was captivated that there might be a theory that explains subjective reports from the ground up, reliant only on the nuts and bolts of cognitive psychology. Here was a potential roadmap for understanding consciousness: if we could show how A connects to B, B connects to C, and C connects to the verbalization “I am conscious of the green of the grass” then we have done our job as scientists. But there was a nagging doubt: does this really explain our inner, subjective experience? Sure, it might explain the report, but it seems to be throwing out the conscious baby with the bathwater. In playful mood, some philosophers have suggested that Dennett himself might be a zombie because for him, the only relevant data on consciousness are the reports of others!

But the problem is that subjective reports are one of the few observable features we have to work with as scientists of consciousness. In Graziano’s theory, the report forms the starting point. He then goes deeper to propose a mechanism underpinning this report that explains conscious experience.

–

To ensure we’re on the same page, let’s start by defining the thing we are trying to explain. Consciousness is a confusing term – some people mean level of consciousness (e.g. coma vs. sleep vs. being awake), others mean self-consciousness, others mean the contents of awareness that we have when we’re awake – an awareness that contains some things, such as the green of an apple, but not others, such as feeling of the clothes against my skin or my heartbeat. Graziano’s theory is about the latter: “The purpose of this book is to present a theory of awareness. How can we become aware of any information at all? What is added to produce awareness?” (p. 14).

What is added to produce awareness? Cognitive psychology and neuroscience assumes that the brain processes information. We don’t yet understand the details of how much of this processing works, but the roadmap is there. Consider a decision about whether you just saw a faint flash of light, such as a shooting star. Under the informational view, the flash causes changes to proteins in the retina, which lead to neural firing, information encoding in visual cortex and so on through a chain of synapses to the verbalization “I just saw a shooting star over there”. There is, in principle, nothing mysterious about this utterance. But why is it accompanied by awareness?

Scientists working on consciousness often begin with the input to the system. We say (perhaps to ourselves) “neural firing propagating across visual cortex doesn’t seem to be enough, so let’s look for something extra”. There have been various proposals for this “something extra”: oscillations, synchrony, recurrent activity. But these proposals shift the goalposts – neural oscillations may be associated with awareness, but why should these changes in brain state cause consciousness? Graziano takes the opposite tack, and works from the motor output, the report of consciousness, inwards (it is perhaps no coincidence that he has spent much of his career studying the motor system). Awareness does not emanate from additional processes that are laid on top of vanilla information processing. Instead, he argues, the only thing we can be sure of about consciousness is that it is information. We say “I am conscious of X”, and therefore consciousness causes – in a very mainstream, neuroscientific way – a behavioural report. Rather like finding the source of a river, he suggests that we should start with these reports and work backwards up the river until we find something that resembles its source. It’s a supercharged version of Dennett: the report is not the end-game; instead, the report is our objective starting point.

–

I recently heard a psychiatrist colleague describe a patient who believed that a beer can inside his head was receiving radio signals that were controlling his thoughts. There was little that could be done to shake the delusion – he admitted it was unusual, but he genuinely believed that the beer can was lodged in his skull. As scientist observers we know this can’t be true: we can even place the man inside a CT scanner and show him the absence of a beer can.

But – and this is the crucial move – the beer can does exist for the patient. The beer can is encoded as an internal brain state, and this information leads to the utterance “I have a beer can in my head”. Graziano proposes that consciousness is exactly like the beer can. Consciousness is real, in the sense it is an informational state that leads us to report “I am aware of X”. But there are no additional properties in the brain that make something conscious, beyond the informational state encoding the belief that the person is conscious. Consciousness is, in this way, a collective delusion – if only one of us was constantly saying, “I am conscious” we might be as skeptical as we are in the case of the beer can, and scan his brain saying “But look! You don’t actually have anything that resembles consciousness in there”.

Hmm, I hear you say, this still sounds rather Dennettian. You’ve replaced consciousness with an informational state that leads to report. Surely there is more to it than that? In Graziano’s theory, the “something extra” is a model of attention, called the attention schema. The attention schema supplies the richness behind the report. Attention is the brain’s way of enhancing some signals but not others. If we’re driving along in the country and a sign appears warning of deer crossing the road, we might focus our attention on the grass verges. But attention is a process, of enhancement or suppression. The state of attention is not represented anywhere in the system [1]. Instead, awareness is the brain’s way of representing what attention is doing. This makes the state of attention explicit. By being aware of looking at my laptop while writing these words, the informational content of awareness is “My attention is pointed at my computer screen”.

Graziano suggests that the same process of modeling our own attentional state is applied to (and possibly evolved from) the ability to model the attentional focus of others [2]. And, because consciousness is a model, rather than a reality that either exists or does not, it has an appealing duality to its existence. We can attribute awareness to ourselves. But we can also attribute awareness to something else, such as a friend, our pet dog, or the computer program in the movie “Her”. Crucially, this attribution is independent of whether they each also attribute awareness to themselves.

–

The attention schema theory is a sketch for a testable theory of consciousness grounded in the one thing we can measure: subjective report. It provides a framework for new experiments on consciousness and attention, consciousness and social cognition, and so on. On occasion it over-generalizes. For instance, free will is introduced as just another element of conscious experience. I found myself wondering how a model of attention could explain our experience of causing our actions, as required to account for the sense of agency. Instead, perhaps we should think of the attention schema as a prototype model for different elements of subjective report. For instance, a sense of agency could arise from a model of the decision-making process that allows us to say “I caused that to happen” – a decision schema, rather than an attention schema.

Of course, many problems remain unsolved. How does the theory account for unconscious perception? Does it predict when attention should dissociate from awareness? What would a mechanism for the attention schema look like? How is the modeling done? We may not yet have all the answers, but Graziano’s theory is an important contribution to framing the questions.

*I am currently Executive Director of the ASSC. The views in this post are my own and should not be interpreted as representing those of the ASSC.

[1] This importance of “representational redescription” of implicitly embedded knowledge was anticipated by Clark & Karmiloff-Smith (1992): “What seems certain is that a genuine cognizer must somehow manage a symbiosis of different modes of representation – the first-order connectionist and the multiple levels of more structured kinds” (p. 515). Importantly, representational redescription is not necessary to complete a particular task, but it is necessary to represent how the task is being completed. As Graziano says: “There is no reason for the brain to have any explicit knowledge about the process or dynamics of attention. Water boils but has no knowledge of how it does it. A car can move but has no knowledge of how it does it. I am suggesting, however, that in addition to doing attention, the brain also constructs a description of attention… and awareness is that description” (p. 25). And: “For a brain to be able to report on something, the relevant item can’t merely be present in the brain but must be encoded as information in the form of neural signals that can ultimately inform the speech circuitry.” (p. 147).

[2] Graziano suggests this is not a metacognitive theory of consciousness because it accounts not only for the abstract knowledge that we are aware but also the inherent property of being aware. But this assertion erroneously conflates metacognition with abstract knowledge. Instead, a model of another cognitive process, such as the attention schema as a model of attention, is inherently metacognitive. Currently there is little work on metacognition of attention, but such experiments may provide crucial data for testing the theory.