An article from the June issue of

Discover Magazine posits that schizophrenia is caused by a virus we all carry in our DNA. If this turns out to be true, it could open whole new possibilities for treatment - and more importantly, early detection, before the hallucinations begin.

One important quote from later in the article:

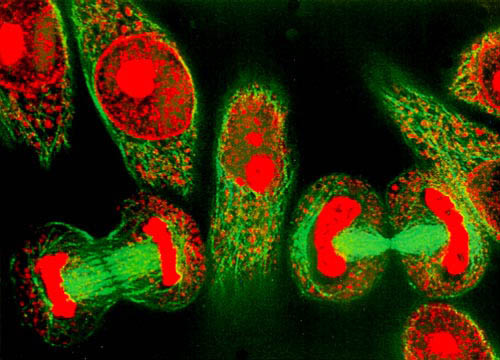

The infection theory could also explain what little we know of the genetics of schizophrenia. One might expect that the disease would be associated with genes controlling our synapses or neurotransmitters. Three major studies published last year in the journal Nature tell a different story. They instead implicate immune genes called human leukocyte antigens (HLAs), which are central to our body’s ability to detect invading pathogens. “That makes a lot of sense,” Yolken says. “The response to an infectious agent may be why person A gets schizophrenia and person B doesn’t.”

Big clue in those studies, along with Dr. Fuller Torrey's observations that the blood of schizophrenics contains immune cells one might expect to see in mononucleosis.

Schizophrenia has long been blamed on bad genes or even bad parents. Wrong, says a growing group of psychiatrists. The real culprit, they claim, is a virus that lives entwined in every person's DNA.

by Douglas Fox From the June 2010 issue; published online November 8, 2010

Steven and David Elmore were born identical twins, but their first days in this world could not have been more different. David came home from the hospital after a week. Steven, born four minutes later, stayed behind in the ICU. For a month he hovered near death in an incubator, wracked with fever from what doctors called a dangerous viral infection. Even after Steven recovered, he lagged behind his twin. He lay awake but rarely cried. When his mother smiled at him, he stared back with blank eyes rather than mirroring her smiles as David did. And for several years after the boys began walking, it was Steven who often lost his balance, falling against tables or smashing his lip.

Those early differences might have faded into distant memory, but they gained new significance in light of the twins’ subsequent lives. By the time Steven entered grade school, it appeared that he had hit his stride. The twins seemed to have equalized into the genetic carbon copies that they were: They wore the same shoulder-length, sandy-blond hair. They were both B+ students. They played basketball with the same friends. Steven Elmore had seemingly overcome his rough start. But then, at the age of 17, he began hearing voices.

The voices called from passing cars as Steven drove to work. They ridiculed his failure to find a girlfriend. Rolling up the car windows and blasting the radio did nothing to silence them. Other voices pursued Steven at home. Three voices called through the windows of his house: two angry men and one woman who begged the men to stop arguing. Another voice thrummed out of the stereo speakers, giving a running commentary on the songs of Steely Dan or Led Zeppelin, which Steven played at night after work. His nerves frayed and he broke down. Within weeks his outbursts landed him in a psychiatric hospital, where doctors determined he had schizophrenia.

The story of Steven and his twin reflects a long-standing mystery in schizophrenia, one of the most common mental diseases on earth, affecting about 1 percent of humanity. For a long time schizophrenia was commonly blamed on cold mothers. More recently it has been attributed to bad genes. Yet many key facts seem to contradict both interpretations.

Schizophrenia is usually diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 25, but the person who becomes schizophrenic is sometimes recalled to have been different as a child or a toddler—more forgetful or shy or clumsy. Studies of family videos confirm this. Even more puzzling is the so-called birth-month effect: People born in winter or early spring are more likely than others to become schizophrenic later in life. It is a small increase, just 5 to 8 percent, but it is remarkably consistent, showing up in 250 studies. That same pattern is seen in people with bipolar disorder or multiple sclerosis.

“The birth-month effect is one of the most clearly established facts about schizophrenia,” says Fuller Torrey, director of the Stanley Medical Research Institute in Chevy Chase, Maryland. “It’s difficult to explain by genes, and it’s certainly difficult to explain by bad mothers.”

The facts of schizophrenia are so peculiar, in fact, that they have led Torrey and a growing number of other scientists to abandon the traditional explanations of the disease and embrace a startling alternative. Schizophrenia, they say, does not begin as a psychological disease. Schizophrenia begins with an infection.

The idea has sparked skepticism, but after decades of hunting, Torrey and his colleagues think they have finally found the infectious agent. You might call it an insanity virus. If Torrey is right, the culprit that triggers a lifetime of hallucinations—that tore apart the lives of writer Jack Kerouac, mathematician John Nash, and millions of others—is a virus that all of us carry in our bodies. “Some people laugh about the infection hypothesis,” says Urs Meyer, a neuroimmunologist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. “But the impact that it has on researchers is much, much, much more than it was five years ago. And my prediction would be that it will gain even more impact in the future.”

The implications are enormous. Torrey, Meyer, and others hold out hope that they can address the root cause of schizophrenia, perhaps even decades before the delusions begin. The first clinical trials of drug treatments are already under way. The results could lead to meaningful new treatments not only for schizophrenia but also for bipolar disorder and multiple sclerosis. Beyond that, the insanity virus (if such it proves) may challenge our basic views of human evolution, blurring the line between “us” and “them,” between pathogen and host.

Read the whole article.

Tags:

Douglas Fox, Discover Magazine, Virus, schizophrenia, The Insanity Virus, DNA, Fuller Torrey, immune system, birth-month effect, infection, Psychology, mental illness, brain, Urs Meyer, neuroimmunology