In the last issue of the Integral Leadership Review, Donna Ladkin published an article on leadership as embodied practice, and she incorporates Maurice Merleau-Ponty, one of the more significant and under-acknowledged philosophers of the 20th Century.

It's an excellent article - and I hope you will go read the whole thing. I am posting here only the sections in which she introduces Merleau-Ponty, as I think it is a good introduction to his ideas. If you want to know more, check out the entry at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy or at the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Perception, Reversibility, “Flesh”: Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology and Leadership as Embodied Practice

Donna Ladkin

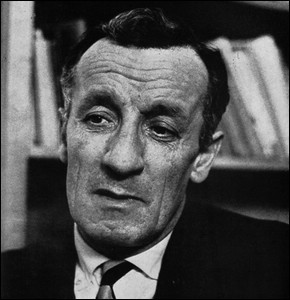

Enter Maurice Merleau-Ponty

The French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961) is probably best known for his major early work, The Phenomenology of Perception (1945). In this text, Merleau-Ponty asserts the “primacy of perception”, arguing that all of the “higher” functions of consciousness, such as reflection and volition, are grounded in “pre-reflective, bodily existence” (Audi 1999: 559). His ideas were developed further in The Visible and the Invisible, an unfinished manuscript at the time of his sudden death in 1961[i]. Together these texts build a philosophy of perception and embodiment that have been unsurpassed in Western philosophy (Leder 1990).

Merleau-Ponty and Embodiment

Merleau-Ponty’s conceptualisation of embodiment is particularly radical by arguing that human bodies are both “immanent” and “transcendent”. Both of these terms have been extensively theorised. Here they are described in the following ways. “Immanence” refers to the material, corporeal flesh and bone aspect of the human body. It is through the immanent body that we experience sensation and are physically present in the world. “Transcendence” refers to those aspects of us that are not material: our intellectual, imaginative and cognitive processes[ii].

Within Western philosophy, certainly since Descartes, the transcendent aspects of being human have been privileged over the immanent aspects. Descartes’ famous pronouncement “cogito ergo sum” (I know myself to be a thinking being) (1988: xxii) has been the touchstone for this emphasis on the thinking, transcendent aspects of being. Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy takes a radically different starting point for his understanding of being human – that without the immanent body, our transcendent consciousness would not exist. It is only because we are embodied that we are able to engage in constant interrogation of the world. Dillon (1997) explains this, writing:

I move in response to the demand of things to be seen as they are, as they need to be seen to respond to the reflexive questions that arise between us. The active, constituting, centrifugal role of the body, its transcendental operation is inconceivable apart from its receptive, responsive existence as flesh amidst the flesh of the world. The body does not synthesise the world ex nihilo; the body seeks understanding from the bodies with which it interacts. (146).This quote highlights the pre-eminent role of the body within Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy. He suggests that we do not just interrogate the world around us through questioning it intellectually, but that our bodies prompt questions as well as responses to the world around us. We are “nested” in contexts that include relationships with people as well as with the world. Drawing links between this insight and the phenomenon of leadership, it becomes clear that as embodied beings, leaders and followers will first and foremost interact with one another as bodies, rather than as “creators of visions”, “authors of mission statements”, or even “hierarchically-determined sources of authority”.

It is important here to stress that the notion of embodiment being used here goes beyond that connoted by the term “body language”. Although body language is an important and often noticed aspect of embodiment, the way one embodies her or himself goes deeper than surface-level body gestures. This includes the way that one’s body holds patterns of tension, one’s energetic quality, the way that one uses his or her voice, patterns and styles of movement, and general quality of bodily presence. All of these aspects are apprehended at a visceral level by other sensing human bodies that respond with their own embodied reactions. Our hearts race with excitement in response to the energetic way in which a message is conveyed before we interpret that embodied response as ‘”feeling inspired”. When our bodies give off reactions congruent with enthusiasm and interest, those who lead us know at a bodily level that they are on the right track and have won our “buy-in”. Thus the space between leaders and followers becomes potent for its ability to inform us about the quality of our interpersonal connections. Merleau-Ponty also notes that within this space and through others’ embodied responses to us, we are also informed about who we, ourselves, are. This idea is elaborated below.

Reversibility and Human Bodies as “Percipient Perceptibles”

A second radical way that Merleau-Ponty conceptualises perception is as a two-way, dynamic and interactive process. In Merleau-Ponty’s rendering, it is impossible for humans to assume the “God perspective” in which they objectively observe the world in such a way that they are not affected by the world observing them back. Human beings cannot perceive without simultaneously being perceived[iii]. Just as I observe another human being, I am aware that he or she can perceive me. The awareness of another’s perception will subsequently alter my awareness of myself. This constant interplay of perception and its implicate sense of being perceived creates the qualitative experience of being in relation to another.

Merleau-Ponty coins the term “percipient perceptibles” to describe this essential way of being in the world and writes of it in this way:

As soon as we see other seers, we no longer have before us only the look without a pupil, the plate glass of things with that feeble reflection, that phantom of ourselves they evoke by designating a place among themselves whence we see them: henceforth, through others’ eyes we are for ourselves fully visible (1968: 143).Merleau-Ponty seems to be suggesting here that it is only through another’s perception that we come to know ourselves. If I bang my hand on the table and raise my voice and others recoil and retreat from me, this tells me that I have been too forceful in this situation (whereas in other situations the same gestures might generate different responses). At close inspection this interactional dynamic is apparent in the relationship between leaders and followers. Leaders only come to know themselves as leaders by acting in relation to perceiving followers; followers too, rely on their leaders to create and contain a sense of identity. In this way, who leaders and followers are to one another is in a constant state of co-creation and flux, determined by perceptual interchanges in the space operating between them.

Merleau-Ponty reminds us that these interpersonal perceptions are based primarily in the experience of our sensate, physical bodies. I am only able to perceive a person as a leader because I have a physical body that stands in material relation to this leader, who in turn stands in physical material reality in relation to me. When I regard that leader from a different physical perspective, I can become aware of different aspects of him or her, and likewise through his or her altered gaze I can experience a change in my own sense of who I am. We are perhaps more accustomed to the way in which seeing another from a different imaginary perspective can change our view, but the important thing to note here is even such imaginal shifts occur because of our embodied ability to physically change where we are in relation to another.

There are a number of interesting implications of this notion of reversibility for leaders and followers. For instance, it is through the perceptions they have of one another, which are generated firstly from their own physical location in relation to each other, that leaders and followers make judgements about one another. For example, we know this from the media’s interest in the way that political and business leaders appear. The huge amount of media coverage and analysis of the photograph released of Barack Obama and his senior team during the operation through which Bin Laden was killed points to the need to arrive at the “truth” of what was going on through an assessment of those individuals’ body postures and tensions, rather than just relying on press reports.

Similarly, new leaders of organisations are often evaluated according to the physical way in which they represent themselves. A recently appointed CEO of a firm for which I consult is spoken about in terms of his lack of attention to his physical appearance. A surprising amount of talk among his senior team focuses on his ill-fitting suits and scuffed shoes. One of his direct reports confided in me, “He would do himself a world of good around the place if he bought himself an expensive suit and got a decent haircut”. Such a comment could be discounted as indicative of society’s over-concerns with appearances and fashion. Interpreted through the lens of Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy however, the senior team of this firm is reacting to what their new CEO’s appearance says about them, who they see themselves to be when they find themselves being led by someone who comports himself as the new CEO does. The notion of “reversibility” alerts us to the important role physical appearance plays in creating the perceptual dynamic between leaders and followers. Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy goes even further in conceptualising this dynamic through his notion of “flesh”, introduced next.

Merleau-Ponty’s Notion of “Flesh”

The notion of “flesh” takes reversibility one step further by suggesting there is visceral substance to intersubjective embodied perception. Not only does flesh encompass the space between leaders and followers, it also includes the “surrounding space” in which these relations are enacted. Perhaps a way of understanding the notion of “flesh” is that it is analogous to an “energetic field” that is both constituted by, and exists between relating entities. Not actually “material” itself, it is experienced as a quality of relational engagement, a “feeling” which can transcend actual geographical distance[iv].

Merleau-Ponty’s notion of “flesh” alerts us to the visceral, invisible but substantive nature of the connection between leaders and followers and the context in which their relations are enacted. It is the energetic “stuff” that holds and carries the quality of leadership relations. For instance, from a Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) perspective, it could be that which distinguishes relationships that create in-group members from those that form out-group members. What the notion of “flesh” highlights that LMX theory does not, is that these relationships are first and foremost based on embodied perceptions.

Attention to the “quality of the flesh of leadership” might add a new way for leaders to think about those relationships. What might a leader do to “fatten” the flesh between him or herself and their followers? A good example of a means by which such relational “flesh” is created and maintained is exemplified by the way in which Obama ran his race for the US presidency in 2008, particularly in terms of the way that he used the Internet. Each morning when I turned my computer on to check my email, there would be a new message from the Senator, his wife, or his running mate, telling his supporters what he was doing and soliciting our ideas and input. Although conducted via email, the way in which he presented himself on the Internet, the visibility he gave himself by appearing on evening talk shows or even the Oprah Winfrey Show, made him available and thickened the “flesh” between himself and his supporters.

These three ideas: the centrality of embodied perception as the ground of interpersonal relations, the way these perceptions create identities through the notion of “reversibility”, and the idea of “flesh” as the “stuff” of materiality, as well as the conduit through which it is perceived, offer new ways of conceptualising the “in-between spaces” at the heart of leader-follower relations. In the section below, an example is introduced to explore their potential for illuminating dimensions of leader-follower relations that are overlooked by cognitive or linguistic approaches.