From Edge, former mathematical trader and current risk manager, and author of

The Black Swan: Second Edition: The Impact of the Highly Improbable: With a new section: "On Robustness and Fragility", Nassim Nicholas Taleb talks about the ideas in his newest book,

Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder.

Here is the publisher's ad-copy for the book:

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, the bestselling author of The Black Swan and one of the foremost thinkers of our time, reveals how to thrive in an uncertain world.

Just as human bones get stronger when subjected to stress and tension, and rumors or riots intensify when someone tries to repress them, many things in life benefit from stress, disorder, volatility, and turmoil. What Taleb has identified and calls “antifragile” is that category of things that not only gain from chaos but need it in order to survive and flourish.

In The Black Swan, Taleb showed us that highly improbable and unpredictable events underlie almost everything about our world. In Antifragile, Taleb stands uncertainty on its head, making it desirable, even necessary, and proposes that things be built in an antifragile manner. The antifragile is beyond the resilient or robust. The resilient resists shocks and stays the same; the antifragile gets better and better.

Furthermore, the antifragile is immune to prediction errors and protected from adverse events. Why is the city-state better than the nation-state, why is debt bad for you, and why is what we call “efficient” not efficient at all? Why do government responses and social policies protect the strong and hurt the weak? Why should you write your resignation letter before even starting on the job? How did the sinking of the Titanic save lives? The book spans innovation by trial and error, life decisions, politics, urban planning, war, personal finance, economic systems, and medicine. And throughout, in addition to the street wisdom of Fat Tony of Brooklyn, the voices and recipes of ancient wisdom, from Roman, Greek, Semitic, and medieval sources, are loud and clear.

Antifragile is a blueprint for living in a Black Swan world.

Erudite, witty, and iconoclastic, Taleb’s message is revolutionary: The antifragile, and only the antifragile, will make it.

That's high praise, but this does look like a very interesting book for those who are into systems thinking.

UNDERSTANDING IS A POOR SUBSTITUTE FOR CONVEXITY (ANTIFRAGILITY)

Nassim Nicholas Taleb [12.12.12]

The point we will be making here is that logically, neither trial and error nor "chance" and serendipity can be behind the gains in technology and empirical science attributed to them. By definition chance cannot lead to long term gains (it would no longer be chance); trial and error cannot be unconditionally effective: errors cause planes to crash, buildings to collapse, and knowledge to regress.

NASSIM NICHOLAS TALEB, essayist and former mathematical trader, is Distinguished Professor of Risk Engineering at NYU’s Polytechnic Institute. He is the author the international bestseller The Black Swan and the recently published Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (Amazon). (US: Random House; UK: Penguin Press)

Nassim Nicholas Taleb's Edge Bio

UNDERSTANDING IS A POOR SUBSTITUTE FOR CONVEXITY (ANTIFRAGILITY)

Something central, very central, is missing in historical accounts of scientific and technological discovery. The discourse and controversies focus on the role of luck as opposed to teleological programs (from telos, "aim"), that is, ones that rely on pre-set direction from formal science. This is a faux-debate: luck cannot lead to formal research policies; one cannot systematize, formalize, and program randomness. The driver is neither luck nor direction, but must be in the asymmetry (or convexity) of payoffs, a simple mathematical property that has lied hidden from the discourse, and the understanding of which can lead to precise research principles and protocols.

MISSING THE ASYMMETRY

The luck versus knowledge story is as follows. Ironically, we have vastly more evidence for results linked to luck than to those coming from the teleological, outside physics—even after discounting for the sensationalism. In some opaque and nonlinear fields, like medicine or engineering, the teleological exceptions are in the minority, such as a small number of designer drugs. This makes us live in the contradiction that we largely got here to where we are thanks to undirected chance, but we build research programs going forward based on direction and narratives. And, what is worse, we are fully conscious of the inconsistency.

The point we will be making here is that logically, neither trial and error nor "chance" and serendipity can be behind the gains in technology and empirical science attributed to them. By definition chance cannot lead to long term gains (it would no longer be chance); trial and error cannot be unconditionally effective: errors cause planes to crash, buildings to collapse, and knowledge to regress.

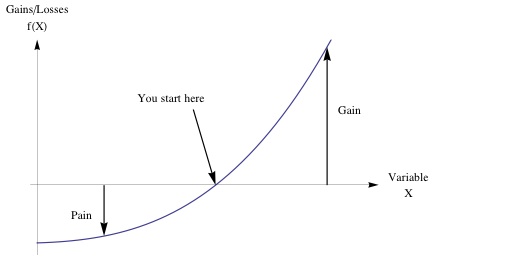

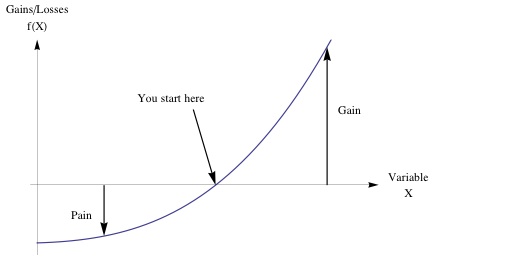

The beneficial properties have to reside in the type of exposure, that is, the payoff function and not in the "luck" part: there needs to be a significant asymmetry between the gains (as they need to be large) and the errors (small or harmless), and it is from such asymmetry that luck and trial and error can produce results. The general mathematical property of this asymmetry is convexity (which is explained in Figure 1); functions with larger gains than losses are nonlinear-convex and resemble financial options. Critically, convex payoffs benefit from uncertainty and disorder. The nonlinear properties of the payoff function, that is, convexity, allow us to formulate rational and rigorous research policies, and ones that allow the harvesting of randomness.

Figure 1- More Gain than Pain from a Random Event. The performance curves outward, hence looks "convex". Anywhere where such asymmetry prevails, we can call it convex, otherwise we are in a concave position. The implication is that you are harmed much less by an error (or a variation) than you can benefit from it, you would welcome uncertainty in the long run.

OPAQUE SYSTEMS AND OPTIONALITY

Further, it is in complex systems, ones in which we have little visibility of the chains of cause-consequences, that tinkering, bricolage, or similar variations of trial and error have been shown to vastly outperform the teleological—it is nature's modus operandi. But tinkering needs to be convex; it is imperative. Take the most opaque of all, cooking, which relies entirely on the heuristics of trial and error, as it has not been possible for us to design a dish directly from chemical equations or reverse-engineer a taste from nutritional labels. We take hummus, add an ingredient, say a spice, taste to see if there is an improvement from the complex interaction, and retain if we like the addition or discard the rest. Critically we have the option, not the obligation to keep the result, which allows us to retain the upper bound and be unaffected by adverse outcomes.

This "optionality" is what is behind the convexity of research outcomes. An option allows its user to get more upside than downside as he can select among the results what fits him and forget about the rest (he has the option, not the obligation). Hence our understanding of optionality can be extended to research programs — this discussion is motivated by the fact that the author spent most of his adult life as an option trader. If we translate François Jacob's idea into these terms, evolution is a convex function of stressors and errors —genetic mutations come at no cost and are retained only if they are an improvement (i). So are the ancestral heuristics and rules of thumbs embedded in society; formed like recipes by continuously taking the upper-bound of "what works". But unlike nature where choices are made in an automatic way via survival, human optionality requires the exercise of rational choice to ratchet up to something better than what precedes it —and, alas, humans have mental biases and cultural hindrances that nature doesn't have. Optionality frees us from the straightjacket of direction, predictions, plans, and narratives. (To use a metaphor from information theory, if you are going to a vacation resort offering you more options, you can predict your activities by asking a smaller number of questions ahead of time.)

While getting a better recipe for hummus will not change the world, some results offer abnormally large benefits from discovery; consider penicillin or chemotherapy or potential clean technologies and similar high impact events ("Black Swans"). The discovery of the first antimicrobial drugs came at the heel of hundreds of systematic (convex) trials in the 1920s by such people as Domagk whose research program consisted in trying out dyes without much understanding of the biological process behind the results. And unlike an explicit financial option for which the buyer pays a fee to a seller, hence tend to trade in a way to prevent undue profits, benefits from research are not zero-sum.

THINGS LOVE UNCERTAINTY

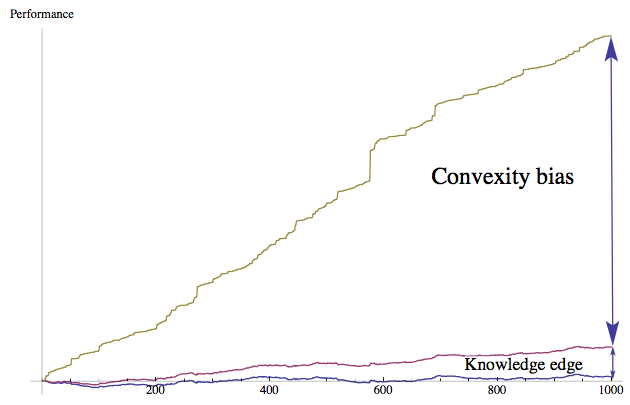

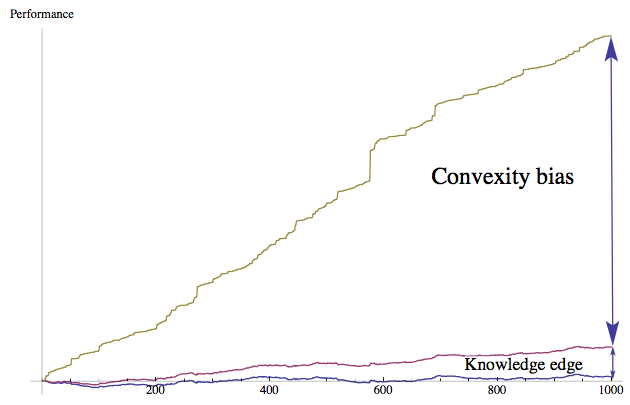

What allows us to map a research funding and investment methodology is a collection of mathematical properties that we have known heuristically since at least the 1700s and explicitly since around 1900 (with the results of Johan Jensen and Louis Bachelier). These properties identify the inevitability of gains from convexity and the counterintuitive benefit of uncertainty (ii, iii). Let us call the "convexity bias" the difference between the results of trial and error in which gains and harm are equal (linear), and one in which gains and harm are asymmetric ( to repeat, a convex payoff function). The central and useful properties are that a) The more convex the payoff function, expressed in difference between potential benefits and harm, the larger the bias. b) The more volatile the environment, the larger the bias. This last property is missed as humans have a propensity to hate uncertainty.

Antifragile is the name this author gave (for lack of a better one) to the broad class of phenomena endowed with such a convexity bias, as they gain from the "disorder cluster", namely volatility, uncertainty, disturbances, randomness, and stressors. The antifragile is the exact opposite of the fragile which can be defined as hating disorder. A coffee cup is fragile because it wants tranquility and a low volatility environment, the antifragile wants the opposite: high volatility increases its welfare. This latter attribute, gaining from uncertainty, favors optionality over the teleological in an opaque system, as it can be shown that the teleological is hurt under increased uncertainty. The point can be made clear with the following. When you inject uncertainty and errors into airplane ride (the fragile or concave case) the result is worsened, as errors invariably lead to plane delays and increased costs —not counting a potential plane crash. The same with bank portfolios and fragile constructs. But it you inject uncertainty into a convex exposure such as some types of research, the result improves, since uncertainty increases the upside but not the downside. This differential maps the way. The convexity bias, unlike serendipity et al., can be defined, formalized, identified, even on the occasion measured scientifically, and can lead to a formal policy of decision making under uncertainty, and classify strategies based on their ex ante predicted efficiency and projected success, as we will do next with the following 7 rules.

Figure 2 The Antifragility Edge (Convexity Bias). A random simulation shows the difference between a) the process with convex trial and error (antifragile) b) a process of pure knowledge devoid of convex tinkering (knowledge based), c) the process of nonconvex trial and error; where errors are equal in harm and gains (pure chance). As we can see there are domains in which rational and convex tinkering dwarfs the effect of pure knowledge (iv).

SEVEN RULES OF ANTIFRAGILITY (CONVEXITY) IN RESEARCH

Next I outline the rules. In parentheses are fancier words that link the idea to option theory.

1) Convexity is easier to attain than knowledge (in the technical jargon, the "long-gamma" property): As we saw in Figure 2, under some level of uncertainty, we benefit more from improving the payoff function than from knowledge about what exactly we are looking for. Convexity can be increased by lowering costs per unit of trial (to improve the downside).

2) A "1/N" strategy is almost always best with convex strategies (the dispersion property):following point (1) and reducing the costs per attempt, compensate by multiplying the number of trials and allocating 1/N of the potential investment across N investments, and make N as large as possible. This allows us to minimize the probability of missing rather than maximize profits should one have a win, as the latter teleological strategy lowers the probability of a win. A large exposure to a single trial has lower expected return than a portfolio of small trials.

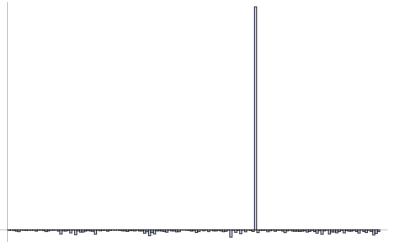

Further, research payoffs have "fat tails", with results in the "tails" of the distribution dominating the properties; the bulk of the gains come from the rare event, "Black Swan": 1 in 1000 trials can lead to 50% of the total contributions—similar to size of companies (50% of capitalization often comes from 1 in 1000 companies), bestsellers (think Harry Potter), or wealth. And critically we don't know the winner ahead of time.

Figure 3-Fat Tails: Small Probability, High Impact Payoffs: The horizontal line can be the payoff over time, or cross-sectional over many simultaneous trials.

3) Serial optionality (the cliquet property). A rigid business plan gets one locked into a preset invariant policy, like a highway without exits —hence devoid of optionality. One needs the ability to change opportunistically and "reset" the option for a new option, by ratcheting up, and getting locked up in a higher state. To translate into practical terms, plans need to 1) stay flexible with frequent ways out, and, counter to intuition 2) be very short term, in order to properly capture the long term. Mathematically, five sequential one-year options are vastly more valuable than a single five-year option.

This explains why matters such as strategic planning have never born fruit in empirical reality: planning has a side effect to restrict optionality. It also explains why top-down centralized decisions tend to fail.

4) Nonnarrative Research (the optionality property). Technologists in California "harvesting Black Swans" tend to invest with agents rather than plans and narratives that look good on paper, and agents who know how to use the option by opportunistically switching and ratcheting up —typically people try six or seven technological ventures before getting to destination. Note the failure in "strategic planning" to compete with convexity.

5) Theory is born from (convex) practice more often than the reverse (the nonteleological property). Textbooks tend to show technology flowing from science, when it is more often the opposite case, dubbed the "lecturing birds on how to fly" effect (v, vi). In such developments as the industrial revolution (and more generally outside linear domains such as physics), there is very little historical evidence for the contribution of fundamental research compared to that of tinkering by hobbyists. (vii) Figure 2 shows, more technically how in a random process characterized by "skills" and "luck", and some opacity, antifragility —the convexity bias— can be shown to severely outperform "skills". And convexity is missed in histories of technologies, replaced with ex post narratives.

6) Premium for simplicity (the less-is-more property). It took at least five millennia between the invention of the wheel and the innovation of putting wheels under suitcases. It is sometimes the simplest technologies that are ignored. In practice there is no premium for complexification; in academia there is. Looking for rationalizations, narratives and theories invites for complexity. In an opaque operation to figure out ex ante what knowledge is required to navigate is impossible.

7) Better cataloguing of negative results (the via negativa property). Optionality works by negative information, reducing the space of what we do by knowledge of what does not work. For that we need to pay for negative results.

Some of the critics of these ideas —over the past two decades— have been countering that this proposal resembles buying "lottery tickets". Lottery tickets are patently overpriced, reflecting the "long shot bias" by which agents, according to economists, overpay for long odds. This comparison, it turns out is fallacious, as the effect of the long shot bias is limited to artificial setups: lotteries are sterilized randomness, constructed and sold by humans, and have a known upper bound. This author calls such a problem the "ludic fallacy". Research has explosive payoffs, with unknown upper bound —a "free option", literally. And we have evidence (from the performance of banks) that in the real world, betting against long shots does not pay, which makes research a form of reverse-banking (viii).

NOTES

i Jacob, F. , 1977, Evolution and tinkering. Science, 196(4295):1161–1166.

ii Bachelier, L. ,1900, Theorie de la spéculation, Gauthiers Villard.

iii Jensen, J.L.W.V., 1906, “Sur les fonctions convexes et les inégalités entre les valeurs moyennes.” Acta Mathematica 30.

iv Take F[x] = Max[x,0], where x is the outcome of trial and error and F is the payoff. ∫ F(x) p(x) dx ≥ F(∫ x p(x)) , by Jensen's inequality. The difference between the two sides is the convexity bias, which increases with uncertainty.

v Taleb, N., and Douady, R., 2013, "Mathematical Definition and Mapping of (Anti)Fragility",f.. Quantitative Finance

vi Mokyr, Joel, 2002, The Gifts of Athena: Historical Origins of the Knowledge Economy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

vii Kealey, T., 1996, The Economic Laws of Scientific Research. London: Macmillan.

viii Briys, E., Nock,R. ,& Magdalou, B., 2012, Convexity and Conflation Biases as Bregman Divergences: A note on Taleb's Antifragile.