Electrical stimulation of a small brain area reversibly disrupts consciousness

Mohamad Z. Koubeissi, Fabrice Bartolomei, Abdelrahman Beltagy, Fabienne Picard

The article is paywalled, of course (Science Direct are thieves), so it will cost you $39.95 to read it.

DOI: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.05.027

Abstract

The neural mechanisms that underlie consciousness are not fully understood. We describe a region in the human brain where electrical stimulation reproducibly disrupted consciousness. A 54-year-old woman with intractable epilepsy underwent depth electrode implantation and electrical stimulation mapping. The electrode whose stimulation disrupted consciousness was between the left claustrum and anterior-dorsal insula. Stimulation of electrodes within 5 mm did not affect consciousness. We studied the interdependencies among depth recording signals as a function of time by nonlinear regression analysis (h2 coefficient) during stimulations that altered consciousness and stimulations of the same electrode at lower current intensities that were asymptomatic. Stimulation of the claustral electrode reproducibly resulted in a complete arrest of volitional behavior, unresponsiveness, and amnesia without negative motor symptoms or mere aphasia. The disruption of consciousness did not outlast the stimulation and occurred without any epileptiform discharges. We found a significant increase in correlation for interactions affecting medial parietal and posterior frontal channels during stimulations that disrupted consciousness compared with those that did not. Our findings suggest that the left claustrum/anterior insula is an important part of a network that subserves consciousness and that disruption of consciousness is related to increased EEG signal synchrony within frontal–parietal networks.

Getting back to the claustrum, according to the late Francis Crick and Christof Koch (2005):

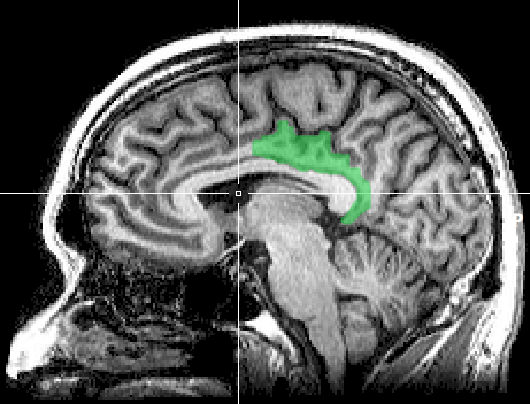

The claustrum is a thin, irregular, sheet-like neuronal structure hidden beneath the inner surface of the neocortex in the general region of the insula. Its function is enigmatic. Its anatomy is quite remarkable in that it receives input from almost all regions of cortex and projects back to almost all regions of cortex.Crick and Koch believe that the claustrum "appears to be in an ideal position to integrate the most diverse kinds of information that underlie conscious perception, cognition and action."

Some of the sensory integration aspects of the claustrum have been called into question by more recent studies, so the claustrum remains an enigma.

However, the buzz generated by this recent study has overlooked the fact that this was not a normal brain - the patient has epilepsy and part of her hippocampus has been removed to control the seizures.

On the other hand, it does offer a new piece of information in that she was awake and not asleep or in a coma, under anesthesia, or in a vegetative state.

Rather than discussing this discovery as having found an on/off switch for consciousness, which feels to me very reductionist, it might be useful to look at how this tiny region of the brain plays a role in integrating the lower (reptilian) brain with the higher (mammalian) brain.

Further, it might be useful to then look at the posteromedial cortices (PMCs), one of what Antonio Damasio describes as convergence-divergence regions or CDRegions (see Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain, 2010).

CDRegions are strategically located within high-order association cortices but not within the image-making sensory cortices. They surface in sites such as the temporoparietal junction, the lateral and medial temporal cortices, the lateral parietal cortices, the lateral and medial frontal cortices, and the posteromedial cortices. These CDRegions hold records of previously acquired knowledge regarding the most diverse themes. The activation of any of these regions promotes the reconstruction, by means of divergence and retroactivation into image-making areas, of varied aspects of past knowledge, including those that pertain to one’s biography, as well as those that describe genetic, nonpersonal knowledge.And:

One of the main CDRegions, the posteromedial cortices (PMCs), appears to have a higher functional hierarchy relative to the others and exhibits several anatomical and functional traits that distinguish it from the rest. A decade ago I suggested that the PMC region was linked to the self process, albeit not in the role I now envision. Evidence obtained in recent years suggests that the PMC region is indeed involved in consciousness, quite specifically in self-related processes, and has provided previously unavailable information regarding the neuroanatomy and physiology of the region.And:

The final candidate is a dark horse, a mysterious structure known as the claustrum, which is closely related to the CDRegions. The claustrum, which is located between the insular cortex and the basal ganglia of each hemisphere, has cortical connections that might potentially play a coordinating role. ... The evidence from experimental neuroanatomy does reveal connections to varied sensory regions, thus making the coordinating role quite plausible. Intriguingly, it has a robust projection to the important CDRegion that I mentioned earlier, the PMC.Clearly, according to Damasio, there is some connection between the claustrum and the PMC, and this would make a lot more sense in that most brain functions are carried out in parallel processes, not in linear processes.

It may be that stimulating the claustrum with an electrical charge disrupts a primary switching point in the brain that helps organize conscious experience, and that rather than being an off-switch for consciousness, the brain "goes offline" so as not to engender further damage. It might be little more than a system protection mechanism (like the "blue screen" in Microsoft Windows - the computer isn't dead, but it shut itself off to protect the system).

Consciousness on-off switch discovered deep in brain

02 July 2014 by Helen Thomson

Magazine issue 2976.

ONE moment you're conscious, the next you're not. For the first time, researchers have switched off consciousness by electrically stimulating a single brain area.

Scientists have been probing individual regions of the brain for over a century, exploring their function by zapping them with electricity and temporarily putting them out of action. Despite this, they have never been able to turn off consciousness – until now.

Although only tested in one person, the discovery suggests that a single area – the claustrum – might be integral to combining disparate brain activity into a seamless package of thoughts, sensations and emotions. It takes us a step closer to answering a problem that has confounded scientists and philosophers for millennia – namely how our conscious awareness arises.

Many theories abound but most agree that consciousness has to involve the integration of activity from several brain networks, allowing us to perceive our surroundings as one single unifying experience rather than isolated sensory perceptions.

One proponent of this idea was Francis Crick, a pioneering neuroscientist who earlier in his career had identified the structure of DNA. Just days before he died in July 2004, Crick was working on a paper that suggested our consciousness needs something akin to an orchestra conductor to bind all of our different external and internal perceptions together.

With his colleague Christof Koch, at the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle, he hypothesised that this conductor would need to rapidly integrate information across distinct regions of the brain and bind together information arriving at different times. For example, information about the smell and colour of a rose, its name, and a memory of its relevance, can be bound into one conscious experience of being handed a rose on Valentine's day.

The pair suggested that the claustrum – a thin, sheet-like structure that lies hidden deep inside the brain – is perfectly suited to this job (Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society B, doi.org/djjw5m).

It now looks as if Crick and Koch were on to something. In a study published last week, Mohamad Koubeissi at the George Washington University in Washington DC and his colleagues describe how they managed to switch a woman's consciousness off and on by stimulating her claustrum. The woman has epilepsy so the team were using deep brain electrodes to record signals from different brain regions to work out where her seizures originate. One electrode was positioned next to the claustrum, an area that had never been stimulated before.

When the team zapped the area with high frequency electrical impulses, the woman lost consciousness. She stopped reading and stared blankly into space, she didn't respond to auditory or visual commands and her breathing slowed. As soon as the stimulation stopped, she immediately regained consciousness with no memory of the event. The same thing happened every time the area was stimulated during two days of experiments (Epilepsy and Behavior, doi.org/tgn).

To confirm that they were affecting the woman's consciousness rather than just her ability to speak or move, the team asked her to repeat the word "house" or snap her fingers before the stimulation began. If the stimulation was disrupting a brain region responsible for movement or language she would have stopped moving or talking almost immediately. Instead, she gradually spoke more quietly or moved less and less until she drifted into unconsciousness. Since there was no sign of epileptic brain activity during or after the stimulation, the team is sure that it wasn't a side effect of a seizure.

Koubeissi thinks that the results do indeed suggest that the claustrum plays a vital role in triggering conscious experience. "I would liken it to a car," he says. "A car on the road has many parts that facilitate its movement – the gas, the transmission, the engine – but there's only one spot where you turn the key and it all switches on and works together. So while consciousness is a complicated process created via many structures and networks – we may have found the key."

Awake but unconscious

Counter-intuitively, Koubeissi's team found that the woman's loss of consciousness was associated with increased synchrony of electrical activity, or brainwaves, in the frontal and parietal regions of the brain that participate in conscious awareness. Although different areas of the brain are thought to synchronise activity to bind different aspects of an experience together, too much synchronisation seems to be bad. The brain can't distinguish one aspect from another, stopping a cohesive experience emerging.

Since similar brainwaves occur during an epileptic seizure, Koubeissi's team now plans to investigate whether lower frequency stimulation of the claustrum could jolt them back to normal. It may even be worth trying for people in a minimally conscious state, he says. "Perhaps we could try to stimulate this region in an attempt to push them out of this state."

Anil Seth, who studies consciousness at the University of Sussex, UK, warns that we have to be cautious when interpreting behaviour from a single case study. The woman was missing part of her hippocampus, which was removed to treat her epilepsy, so she doesn't represent a "normal" brain, he says.

However, he points out that the interesting thing about this study is that the person was still awake. "Normally when we look at conscious states we are looking at awake versus sleep, or coma versus vegetative state, or anaesthesia." Most of these involve changes of wakefulness as well as consciousness but not this time, says Seth. "So even though it's a single case study, it's potentially quite informative about what's happening when you selectively modulate consciousness alone."

"Francis would have been pleased as punch," says Koch, who was told by Crick's wife that on his deathbed, Crick was hallucinating an argument with Koch about the claustrum and its connection to consciousness.

"Ultimately, if we know how consciousness is created and which parts of the brain are involved then we can understand who has it and who doesn't," says Koch. "Do robots have it? Do fetuses? Does a cat or dog or worm? This study is incredibly intriguing but it is one brick in a large edifice of consciousness that we're trying to build."

This article appeared in print under the headline "Consciousness – we hit its sweet spot"