Slavoj Žižek has lost some of the star-status he enjoyed a year or two ago when he seemed to translated and profiled nearly weekly in U.S. journals. His rise to fame began with the 1989 translation into English of The Sublime Object of Ideology and continued to increase over the next two decades, perhaps peaking in 2009-2010 when he was reportedly hanging out with Lady Gaga.

From my perspective it seemed he was seeking controversy and probably hoped to generate discussion, but generally came to be regarded as something of a buffoon by more serious authors and critics. Maybe that is for the best - he does not feel the philosopher or social critic should pretend to have answers in the first place.

Here is a brief summary of his "thinking" from Wikipedia:

Ian Parker claims that there is no "Žižekian" system of philosophy because Žižek, with all his inconsistencies, is trying to make us think much harder about what we are willing to believe and accept from a single writer (Parker, 2004). Indeed, Žižek himself defends Jacques Lacan for constantly updating his theories, arguing that it is not the task of the philosopher to act as the Big Other who tells us about the world but rather to challenge our own ideological presuppositions. The philosopher, for Žižek, is more someone engaged in critique than someone who tries to answer questions.[24]

However, this claim about the role of the philosopher/theorist is complicated by how Žižek frequently derides the consumerist fashionability of postmodern cultural criticism while affirming his universal emancipatory stance and love for "grand explanations" (Žižek, 2008). In contrast to Parker, Adrian Johnston's book Zizek's Ontology: A Transcendental Materialist Theory of Subjectivity argues against the position that Žižek's thought has no consistency or underlying project. Specifically, Johnston claims in his Preface that beneath "what could be called 'the cultural studies Žižek'" is a singular "philosophical trajectory that runs like a continuous, bisecting diagonal line through the entire span of his writing (i.e. the retroactive Lacanian reconstruction of the chain Kant-Schelling-Hegel)." Žižek's affirmation of this claim suggests that like his predecessor Hegel, Žižek's work is better described as rigorous in the sense of systematic rather than as comprising a single, all-encompassing "system."

One thing Žižek has always done well is film criticism. He brings the same bastardized hybrid of Lacanian psychoanalysis, Hegelian phenomenology, and Marxist social theory to film that he generally brings to discussions of social and political issues.

In this recent article from New Statesman, he looks at the politics of Batman as revealed in the final Christopher Nolan installment, The Dark Knight Rises. The article contains spoilers for those who have not yet seen the film - read at your own risk.

Slavoj Žižek: The politics of Batman

From the repression of unruly citizens to the celebration of the “good capitalist”, The Dark Knight Rises reflects our age of anxiety.

By Slavoj Zizek Published 23 August 2012

The Dark Knight Rises shows that Hollywood blockbusters are precise indicators of the ideological predicaments of our societies. Here is the storyline. Eight years after the events of The Dark Knight, the previous installment of Christopher Nolan’s Batman series, law and order prevail in Gotham City. Under the extraordinary powers granted by the Dent Act, Commissioner Gordon has nearly eradicated violent and organised crime. He nonetheless feels guilty about the cover-up of the crimes of Harvey Dent and plans to confess to the conspiracy at a public event – but he decides that the city is not ready to hear the truth.

No longer active as Batman, Bruce Wayne lives isolated in his manor. His company is crumbling after he invested in a clean-energy project designed to harness fusion power but then shut it down, on learning that the core could be modified to become a nuclear weapon. The beautiful Miranda Tate, a member of the Wayne Enterprises executive board, encourages Wayne to rejoin society and continue his philanthropic good works.

Here enters the first villain of the film. Bane, a terrorist leader who was a member of the League of Shadows, gets hold of a copy of the commissioner’s speech. After Bane’s financial machinations bring Wayne’s company close to bankruptcy, Wayne entrusts control of his enterprise to Miranda and also has a brief love affair with her. Learning that Bane has also got hold of his fusion core, Wayne returns as Batman and confronts Bane. Crippling Batman in close combat, Bane detains him in a prison from which escape is almost impossible. While the imprisoned Wayne recovers from his injuries and retrains himself to be Batman, Bane succeeds in turning Gotham City into an isolated city state. He first lures most of Gotham’s police force underground and traps them there; then he sets off explosions that destroy most of the bridges connecting Gotham to the mainland and announces that any attempt to leave the city will result in the detonation of Wayne’s fusion core, which has been converted into a bomb.

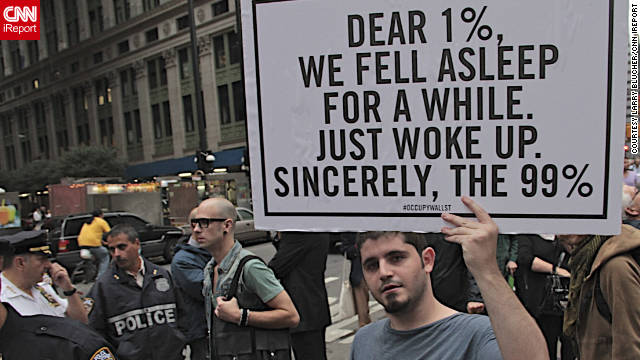

Now we reach the crucial moment of the film: Bane’s takeover is accompanied by a vast politico-ideological offensive. He publicly exposes the cover-up of Dent’s death and releases the prisoners locked up under the Dent Act. Condemning the rich and powerful, he promises to restore the power of the people, calling on citizens, “Take your city back.” Bane reveals himself, as the critic Tyler O’Neil has put it, to be “the ultimate Wall Street Occupier, calling on the 99 per cent to band together and overthrow societal elites”. What follows is the film’s idea of people power – summary show trials and executions of the rich, the streets surrendered to crime and villainy.

A couple of months later, while Gotham City continues to suffer under popular terror, Wayne escapes from prison, returns as Batman and enlists his friends to help liberate the city and disable the fusion bomb before it explodes. Batman confronts and subdues Bane but Miranda intervenes and stabs Batman. She reveals herself to be Talia al-Ghul, daughter of Ra’s al-Ghul, the former leader of the League of Shadows (the villains in Batman Begins). After announcing her plan to complete her father’s work in destroying Gotham City, Talia escapes.

In the ensuing mayhem, Commissioner Gordon cuts off the bomb’s remote detonation function, while a benevolent cat burglar named Selina Kyle kills Bane, freeing Batman to chase Talia. He tries to force her to take the bomb to the fusion chamber where it can be stabilised, but she floods the chamber. Talia dies, confident that the bomb cannot be stopped, when her truck is knocked off the road and crashes. Using a special helicopter, Batman hauls the bomb beyond the city limits, where it detonates over the ocean and presumably kills him. Batman is now celebrated as a hero whose sacrifice saved Gotham City. Wayne is believed to have died in the riots. While his estate is being divided up, his butler, Alfred, sees Wayne and Selina together alive in a café in Florence. Blake, a young and honest policeman who knew about Batman’s identity, inherits the Batcave. The first clue to the ideological underpinnings of this ending is provided by Alfred, who, at Wayne’s apparent burial, reads the last lines from Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities: “It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.” Some reviewers took this as an indication that, in O’Neil’s words, the film “rises to the noblest level of western art . . . The film appeals to the centre of America’s tradition – the ideal of noble sacrifice for the common people . . . An ultimate Christ-figure, Batman sacrifices himself to save others.”

Seen from this perspective, the storyline is a short step back from Dickens to Christ at Calvary. But isn’t the idea of Batman’s sacrifice as a repetition of Christ’s death not compromised by the film’s last scene (Wayne with Selina in the café)? Is the religious counterpart of this ending not, instead, the well-known blasphemous idea that Christ survived his crucifixion and lived a long, peaceful life in India or, as some sources have it, Tibet? The only way to redeem this final scene would be to read it as a daydream or hallucination of Alfred’s.

A further Dickensian feature of the film is a depoliticised complaint about the gap between rich and poor. Early in the film, Selina whispers to Wayne as they are dancing at an exclusive, upper-class gala: “A storm is coming, Mr Wayne. You and your friends better batten down the hatches. Because when it hits, you’re all going to wonder how you thought you could live so large and leave so little for the rest of us.” Nolan, like any good liberal, is “worried” about the disparity and has said that this worry permeates the film: “The notion of economic fairness creeps into the film . . . I don’t feel there’s a left or right perspective in the film. What is there is just an honest assessment or honest exploration of the world we live in – things that worry us.”

Although viewers know Wayne is mega-rich, they often forget where his wealth comes from: arms manufacturing plus stock-market speculation, which is why Bane’s games on the stock exchange can destroy his empire. Arms dealer and speculator – this is the secret beneath the Batman mask. How does the film deal with it? By resuscitating the archetypal Dickensian theme of a good capitalist who finances orphanages (Wayne) versus a bad, greedy capitalist (Stryver, as in Dickens). As Nolan’s brother, Jonathan, who co-wrote the screenplay, has said: “A Tale of Two Cities, to me, was the most . . . harrowing portrait of a relatable, recognisable civilisation that had completely fallen to pieces. You look at the Terror in Paris, in France in that period, and it’s hard to imagine that things could go that bad and wrong.” The scenes of the vengeful populist uprising in the film (a mob that thirsts for the blood of the rich who have neglected and exploited them) evoke Dickens’s description of the Reign of Terror, so that, although the film has nothing to do with politics, it follows Dickens’s novel in “honestly” portraying revolutionaries as possessed fanatics.

The good terrorist

An interesting thing about Bane is that the source of his revolutionary hardness is unconditional love. In one touching scene, he tells Wayne how, in an act of love amid terrible suffering, he saved the child Talia, not caring about the consequences and paying a terrible price for it (Bane was beaten to within an inch of his life while defending her).

Another critic, R M Karthick, locates The Dark Knight Rises in a long tradition stretching from Christ to Che Guevara which extols violence as a “work of love”, as Che does in his diary:

Let me say, with the risk of appearing ridiculous, that the true revolutionary is guided by strong feelings of love. It is impossible to think of an authentic revolutionary without this quality.What we encounter here is not so much the “christification of Che” but rather a “cheisation” of Christ – the Christ whose “scandalous” words from Luke (“If anyone comes to me and does not hate his father and his mother, his wife and children, his brothers and sisters – yes, even his own life – he cannot be my disciple”) point in the same direction as these ones from Che: “You may have to be tough but do not lose your tenderness.” The statement that “the true revolutionary is guided by a strong feeling of love” should be read together with Guevara’s much more problematic description of revolutionaries as “killing machines”:

Hatred is an element of struggle; relentless hatred of the enemy that impels us over and beyond the natural limitations of man and transforms us into effective, violent, selective and cold killing machines. Our soldiers must be thus; a people without hatred cannot vanquish a brutal enemy.Guevara here is paraphrasing Christ’s declarations on the unity of love and the sword – in both cases, the underlying paradox is that what makes love angelic, what elevates it over mere sentimentality, is its cruelty, its link with violence. And it is this link that places love beyond the natural limitations of man and thus transforms it into an unconditional drive. This is why, to turn back to The Dark Knight Rises, the only authentic love portrayed in the film is Bane’s, the terrorist’s, in clear contrast to Batman’s.

The figure of Ra’s, Talia’s father, also deserves a closer look. Ra’s has a mixture of Arab and oriental features and is an agent of virtuous terror, fighting to correct a corrupted western civilisation. He is played by Liam Neeson, an actor whose screen persona usually radiates dignified goodness and wisdom – he is Zeus in Clash of the Titans and also plays Qui-Gon Jinn in The Phantom Menace, the first episode of the Star Wars series. Qui-Gon is a Jedi knight, the mentor of Obi-Wan Kenobi as well as the one who discovers Anakin Skywalker, believing that Anakin is the chosen one who will restore the balance of the universe, and ignores Yoda’s warnings about Anakin’s unstable nature. At the end of The Phantom Menace, Qui-Gon is killed by the assassin Darth Maul.

In the Batman trilogy, Ra’s is the teacher of the young Wayne. In Batman Begins, he finds him in a prison in Bhutan. Introducing himself as Henri Ducard, he offers the boy a “path”. After Wayne is freed, he climbs to the home of the League of Shadows where Ra’s is waiting. At the end of a lengthy and painful period of training, Ra’s explains that Wayne must do what is necessary to fight evil, and that the league has trained Wayne to lead it in its mission to destroy Gotham City, which the league believes has become hopelessly corrupt.

Ra’s is thus not a simple embodiment of evil. He stands for the combination of virtue and terror, for egalitarian discipline fighting a corrupted empire, and thus belongs to a line that stretches in recent fiction from Paul Atreides in Frank Herbert’s Dune to Leonidas in Frank Miller’s graphic novel 300. It is crucial that Wayne was a disciple of Ra’s: Wayne was made into Batman by his mentor.

At this point, two common-sense objections suggest themselves. The first is that there were monstrous mass killings and violence in real-life revolutions, from the rise of Stalin to the rule of the Khmer Rouge, so the film is clearly not just engaging in reactionary imagination. The second objection is that the Occupy Wall Street (OWS) movement in reality was not violent – its goal was definitely not a new Reign of Terror. In so far as Bane’s revolt is supposed to extrapolate the immanent tendency of OWS, the film absurdly misrepresents its aims and strategies. The ongoing anti-capitalist protests are the opposite of Bane: he stands for the mirror image of state terror, for a murderous fundamentalism that takes over and rules by fear, not for the overcoming of state power through popular self-organisation. What both objections share, however, is the rejection of the figure of Bane.

The reply to these two objections has several parts. First, one should make the scope of violence clear. The best answer to the claim that the violent mob reaction to oppression is worse than the original oppression was the one provided by Mark Twain in his novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court:

There were two “Reigns of Terror” if we would remember it and consider it; the one wrought in hot passion, the other in heartless cold blood . . . Our shudders are all for the “horrors” of the minor Terror, the momentary Terror, so to speak, whereas, what is the horror of swift death by the axe compared with lifelong death from hunger, cold, insult, cruelty, and heartbreak? . . . A city cemetery could contain the coffins filled by that brief Terror which we have all been so diligently taught to shiver at and mourn over; but all France could hardly contain the coffins filled by that older and real Terror, that unspeakably bitter and awful Terror, which none of us have been taught to see in its vastness or pity as it deserves.Then, one should demystify the problem of violence, rejecting simplistic claims that 20th- century communism used too much extreme murderous violence. We should be careful not to fall into this trap again. As a fact, this is terrifyingly true. Yet such a direct focus on violence obfuscates the underlying question: what was wrong with the communist project as such? What internal weakness of that project was it that pushed communists towards unrestrained violence? It is not enough to say that communists neglected the “problem of violence”; it was a deeper, sociopolitical failure that pushed them to violence. It is thus not only Nolan’s film that is unable to imagine authentic people’s power. The “real” radical-emancipatory movements couldn’t do it, either; they remained caught in the co-ordinates of the old society, in which actual “people power” was often such a violent horror.

Finally, it is all too simplistic to claim that there is no violent potential in OWS and similar movements – there is a violence at work in every authentic emancipatory process. The problem with The Dark Knight Rises is that it has wrongly translated this violence into murderous terror. Let us take a brief detour here through José Saramago’s novel Seeing, which tells the story of strange events in the unnamed capital city of an unidentified democratic country. When election day dawns with torrential rain, the voter turnout is disturbingly low. But the weather turns by mid-afternoon and the population heads en masse to the polling stations. The government’s relief is short-lived, however: the count shows that more than 70 per cent of the ballots cast in the capital have been left blank. Baffled, the government gives the people a chance to make amends a week later at another election.

The results are worse. Now 83 per cent of the ballots are blank. The two major political parties – the ruling party of the right and its chief adversary, the party of the middle – are in a panic, while the marginalised party of the left produces an analysis claiming that the blank ballots are a vote for its progressive agenda. Unsure how to respond to a benign protest but certain that an anti-democratic conspiracy is afoot, the government quickly labels the movement “terrorism, pure and unadulterated” and declares a state of emergency.

Citizens are seized at random and disappear into secret interrogation sites; the police and seat of government are withdrawn from the capital; all entrances to the city are sealed, as are the exits. The city continues to function almost normally throughout, the people parrying each of the government’s thrusts in unison and with a Gandhian level of non-violent resistance. This, the voters’ abstention, is a case of authentically radical “divine violence” that prompts panic reactions from those in power.

Back to Nolan. The trilogy of Batman films follows an internal logic. In Batman Begins, the hero remains within the constraints of a liberal order: the system can be defended with morally acceptable methods. The Dark Knight is, in effect, a new version of two John Ford western classics, Fort Apache and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, which show how, to civilise the Wild West, one has to “print the legend” and ignore the truth. They show, in short, how our civilisation has to be grounded in a lie – one has to break the rules in order to defend the system.

In Batman Begins, the hero is simply the classic urban vigilante who punishes the criminals when the police can’t. The problem is that the police, the official law-enforcement agency, respond ambivalently to Batman’s help. They see him as a threat to their monopoly on power and therefore as evidence of their inefficiency. However, his transgression here is purely formal: it lies in acting on behalf of the law without being legitimised to do so. In his acts, he never violates the law. The Dark Knight changes these co-ordinates. Batman’s true rival is not his ostensible opponent, the Joker, but Harvey Dent, the “white knight”, the aggressive new district attorney, a kind of official vigilante whose fanatical battle against crime leads to the killing of innocent people and ultimately destroys him. It is as if Dent were the legal order’s reply to the threat posed by Batman: against Batman’s vigilantism, the system generates its own illegal excess in a vigilante much more violent than Batman.

There is poetic justice, therefore, when Wayne plans to reveal his identity as Batman and Dent jumps in and names himself as Batman – he is more Batman than Batman, actualising the temptation to break the law that Wayne was able to resist. When, at the end of the film, Batman assumes responsibility for the crimes committed by Dent to save the reputation of the popular hero who embodies hope for ordinary people, his act is a gesture of symbolic exchange: first Dent takes upon himself the identity of Batman, then Wayne – the real Batman – takes Dent’s crimes upon himself.

The Dark Knight Rises pushes things even further. Is Bane not Dent taken to an extreme? Dent draws the conclusion that the system is unjust, so that, to fight injustice effectively, one has to turn directly against the system and destroy it. Dent loses his remaining inhibitions and is ready to use all manner of methods to achieve this goal. The rise of such a figure changes things entirely. For all the characters, Batman included, morality is relativised and becomes a matter of convenience, something determined by circumstances. It’s open class warfare – everything is permitted in defence of the system when we are dealing not just with mad gangsters, but with a popular uprising.

Should the film be rejected by those engaged in emancipatory struggles? Things aren’t quite so simple. We should approach the film in the way one has to interpret a Chinese political poem. Absences and surprising presences count. Recall the old French story about a wife who complains that her husband’s best friend is making illicit sexual advances towards her. It takes some time until the surprised friend gets the point: in this twisted way, she is inviting him to seduce her. It is like the Freudian unconscious that knows no negation; what matters is not a negative judgement of something but that this something is mentioned at all. In The Dark Knight Rises, people power is here, staged as an event, in a significant development from the usual Batman opponents (criminal mega-capitalists, gangsters and terrorists).

Strange attraction

The prospect of the Occupy Wall Street movement taking power and establishing a people’s democracy on the island of Manhattan is so patently absurd, so utterly unrealistic, that one cannot avoid asking the following question – why does a Hollywood blockbuster dream about it? Why does it evoke this spectre? Why does it even fantasise about OWS exploding into a violent takeover? The obvious answer – that it does so to taint OWS with the accusation that it harbours a terrorist or totalitarian potential – is not enough to account for the strange attraction exerted by the prospect of “people power”. No wonder the proper functioning of this power remains blank, absent; no details are given about how the people power functions or what the mobilised people are doing. Bane tells the people they can do what they want – he is not imposing his own order on them. This is why external critique of the film (claiming that its depiction of OWS is a ridiculous caricature) is not enough. The critique has to be immanent; it has to locate inside the film a multitude of signs that point towards the authentic event. (Recall, for instance, that Bane is not just a bloodthirsty terrorist but a person of deep love, with a spirit of sacrifice.)

In short, pure ideology isn’t possible. Bane’s authenticity has to leave traces in the film’s texture. This is why The Dark Knight Rises deserves close reading. The event – the “People’s Republic of Gotham City”, a dictatorship of the proletariat in Manhattan – is immanent to the film. It is its absent centre.

~ Slavoj Žižek’s latest book is “Less Than Nothing: Hegel and the Shadow of Dialectical Materialism” (Verso, £50)