27th September 2014

Today we have something a little different, a very nicely illustrated mapping project reflecting on p2p values and spirituality by Andrius Kulikauskas.

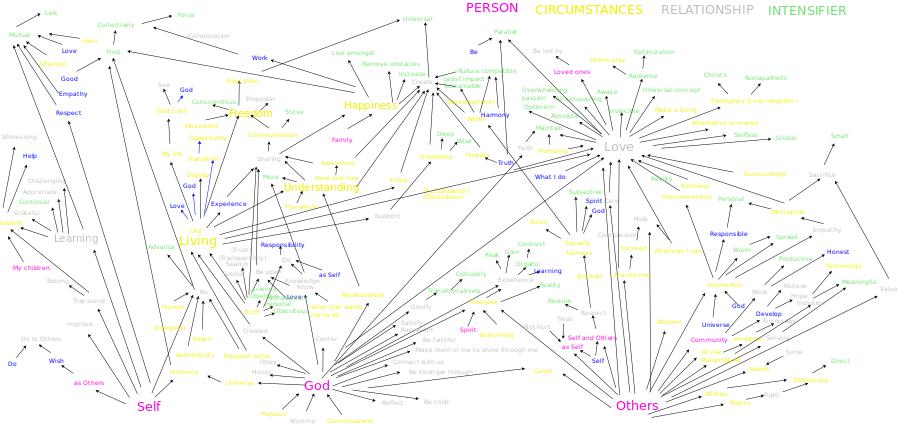

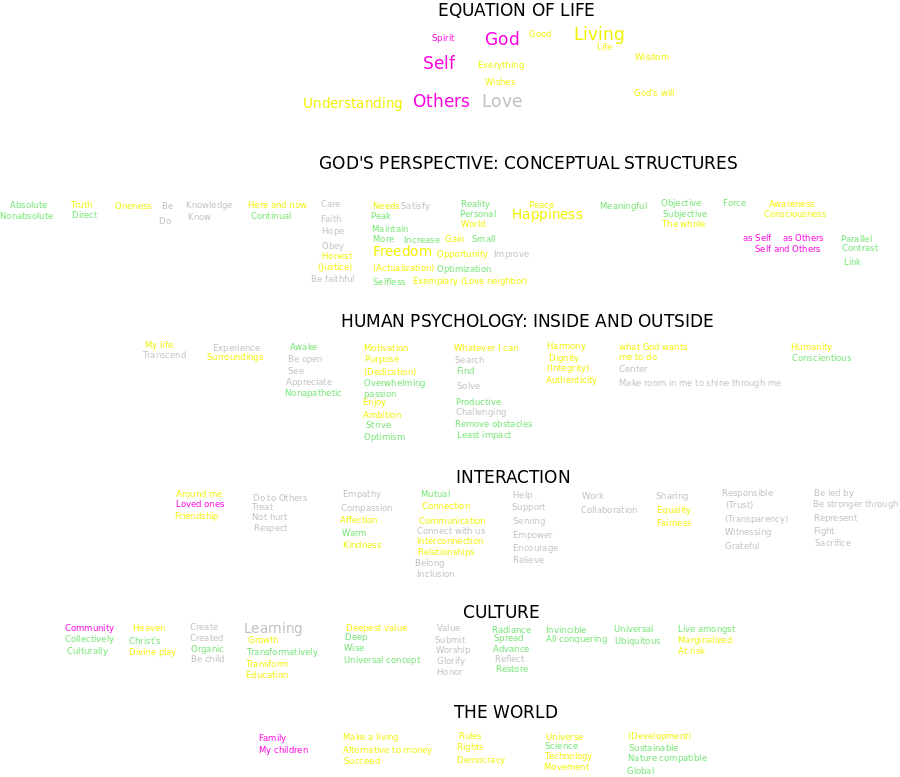

The peer-to-peer movement values relative truth with a passion that is practically absolute. I believe that individual perspectives have the potential to discover the universal truth, at least enough of it so as to make the peer-to-peer movement viable. The path from relative to absolute truth is the subject of my e-book, The Truth, from Relative to Absolute.I think the most practical concept from my book is a person’s deepest value. In 2004, I wondered how my online laboratory Minciu Sodas might organize a Yahoo! group around Franz Nahrada and openly support his many projects. We needed a single concept that summarized what he cared about. For him, it was Global Villages. He later expressed his deepest value in life as optimal interplay. From 2004 to 2010, I organized more than twenty such discussion groups, including Janet Feldman’s Holistic Helping, Pamela McLean’s Learning From Each Other, Samwel Kongere’s Mendenyo (“men without food”, motivation through sacrifice), John Roger’s Cyfranogi (“participate”, participatory society) and my own group Living by Truth. Here is an excerpt from my book:Truth is inside of us, deeper than words. Ask people what they know firsthand:What do they value? What is their deepest value in life which includes all of their other values?They may not have an answer. Or they may feel it but not yet have words for it. Or they may have already thought it through. As the ancient Greeks would say, they know themselves.Their values are all uniquely beautiful: Holistic Helping, Learning From Each Other, Participatory Society, Serving Others, Fighting Peacefully, Synergy, Freedom, Faith, Family, Unity, Love…If two people give the same answer such as Family, and you ask them what they mean by that, they will give you different answers.Their deepest value is their spiritual name, like a Native American name. They will almost always let you share it.It is how they hope to think of themselves. In practice, it is their strong point but also their blind spot. It is what we should have them be in charge of.It is how they are happy to be categorized, how you can empathize with them and hold them accountable.It is their soul, the essence of their personality, their principle which they substitute for themselves, their name which is written in the Book of Life, what is truly eternal.They are thus like stars in the sky, seeing the entire sky from their particular position. As Jesus says, they are born again of the Spirit. They are Allah’s holy names.Their deepest values are all aspects of love, which is surely God’s deepest value. They address what they each think is the problem with this world, the lack of love they feel. It is how they integrate their many values as they clash in daily life.They invest themselves in their deepest value, which does not change but rather grows ever more clear to them. As they know themselves, they dare to go beyond themselves and ask what they do not know.What do they seek to know? What is a question that they don’t know the answer to, but wish to answer?In 10 years, I collected deepest values and investigatory questions from hundreds of people. I think it would be very fruitful to work together to collect many more. They might serve as the basis for appreciating the greatest variety of perspectives and discovering what amongst them might actually be universal.I am working on a map of deepest values and related concepts. I’ve noticed that often a value such as my own “living by absolute truth” breaks do wn into one concept that is given (in my case, “the absolute truth”), and another concept that depends on my choice (“living” that truth). Others value “living by harmony”, “living as a creation of God” and such variations are the basis for my map.I’ve noticed that some values presume very little and might make sense from an abstract God’s point of view. Others, however, are psychological and distinguish internal thinking and external actions as with motivations, obstacles and solutions. There are values which presume two or more beings as with empathy and collaboration. Community, education, glory suppose an entire culture. Family, children, technology, democracy, money, making a living, sustainability and the Bible all depend on the details of the world as we know it. I’d love to work together to sort through the underlying presumptions. I’m also interested in related art projects. I share a letter about my research in English and I’m working on it in Lithuanian.

Offering multiple perspectives from many fields of human inquiry that may move all of us toward a more integrated understanding of who we are as conscious beings.

Showing posts with label perspectives. Show all posts

Showing posts with label perspectives. Show all posts

Tuesday, September 30, 2014

P2P Truth: A Map of Deepest Values by Andrius Kulikauskas

This comes from the P2P Foundation blog. Andrius Kulikauskas offers a unique values of P2P.

Thursday, March 20, 2014

New Issue - Integral Review: Volume 10, No. 1, March 2014

A new issue of Integral Review is online and free to read. This issue features articles by Sara Nora Ross, Bonnitta Roy, and a book review by Zak Stein. An article by Kevin J. Bowman, "Correcting Improper Uses of Perspectives, Pronouns, and Dualities in Wilberian Integral Theory: An Application of Holarchical Field Theory," sounds particularly interesting.

Integral Review

Volume 10, No. 1

March 2014

63 91 122 154 168 179 187

Thursday, December 05, 2013

An Introduction to Mindset Agency Theory

In this paper, Yolles and Fink assemble a mindset theory not at all related to that of Carol Dweck's popular model. Rather, these authors build off of the work of personality modelling approaches which were broadly described as classificational, relational, or dynamic/causational.

Jung’s, Bandura’s and Piaget’s theories are all causational; MBTI and FFM are classificational; and Maruyma’s Mindscape theory is relational. Because of its epistemological and relational basis, we found that Maruyama’s Mindscape theory has a better potential capacity to explore cognitive patterns of personality than MBTI and FFM. However, Maruyama’s Mindscape theory does not have the generative transparency of MBTI. To improve on the generative transparency of Mindscape theory, Boje’s had introduced three “real traits”. However, Boje’s approach remained qualitative without the immediate possibility of empirical support, and is thereby not improving the potential for broader use of Mindscape theory.The result is an interesting values frame and a multi-perspectival model of mindsets.

Moving on from the Introduction, I wanted to share a pretty large section of this paper because I believe it offers an unique and useful model for making sense of values frames in both individual and cultures.An Introduction to Mindset Theory

November 1, 2013

- Maurice Yolles: John Moores University - Centre for the Creation of Coherent Change and Knowledge (C4K)

- Gerhard Fink: IACCM International Association for Cross Cultural Competence and Management

Abstract:

The plural agency is a self-referential, self-regulating, self-organizing, adaptive, pro-active and culturally stable collective, having a normative personality belonging to a psychosocial framework of the "collective mind." The agency can be characterized by Mindset types, a derivative of Maruyama’s Mindscape meta-theory -- a little known but powerful epistemic approach that can anticipate an agency’s patterns of behavior and demands. A Mindscape is a construct from which coherent sets of behavioral mind-sets can emerge. However, Mindscape theory lacks generative transparency, and the Mindset theory we develop changes this. Mindset Theory is based on the Sagiv-Schwartz (2007) cultural values study from which eight Mindset types are generated that individually or in combination can characterize personality and anticipate behavior.

Introduction

This paper is interested in two aspects of personality: a theory of personality that indicates its nature, how it functions, and an identification of variables that might represent its major characteristics, and personality assessment through an ability to identify and evaluate these variables. Our purpose in this paper covers both of these attributes. In respect of the first, we aim at creating a dynamic socio-cognitive theory of human agency having as its core a normative personality.

When we refer to normative personality, we do not mean this within the context of the ambient normative social influences that exist during the formation of personalities and that mould them (Mroczek & Little, 2006). Rather, the term is being used to refer to the norms in a collective that may together coalesce into a unitary cognitive structure such that a collective mind can be inferred, and from which an emergent normative personality arises. To explain this further, consider that a potentially durable collective develops a dominant culture within which shared beliefs arise in relation to its capacity to produce desired operative outcomes. Cultural anchors arise which enable the development of formal and informal norms to which patterns of behaviour, modes of conduct and expression, forms of thought, attitudes, and values are more or less adhered to by those that compose the plural agency. When the norms refer to formal behaviours, then where the members of the collective contravene them, they are deemed to be engaging in illegitimate behaviour which, if discovered, may result in formal retribution - the severity of which is determined from the agency’s ideological and ethical positioning. This occurs with the rise of collective cognitive processes that start with information inputs and through communication and decision processes result in orientation towards action; and it does this with a sense of the collective mind and self. It is a short step to recognise that the collective mind has associated with it a normative personality. Where a normative personality is deemed to exist, it does not necessarily mean that individual members of the collective will all conform to all aspects of the normative processes: they may only do so “more or less.” According to Yolles (2009), as long as a plural agency has a durable culture to which participants more or less conform through its norms, a “collective mind” is implied that operates through meaningful dialogue and agreement. As such the plural agency may appear to behave more or less like a singular cognitive agency. While the plural agency is ultimately composed of singular agencies, they are similar, can suffer from related pathologies that include: dysfunctions, neuroses, feelings of guilt, adopt and maintain collective psychological defences that reduce pain through denial and cover-up, and operate through processes of power that might be unproductive (Kets de Vries, 1991).

In the same way that singular agencies learn, so do plural agencies. We represent this capacity of the normative personality through cognitive learning theory (e.g., Miller & Dollard, 1941; Miller et al., 1960; Piaget, 1950; Vygotsky, 1978; Argyris & Schön, 1978; Bandura, 1991; Nobre, 2003; Argote & Todorova, 2007), where “learning is seen in terms of the acquisition or reorganization of the cognitive structures through which agencies process and store information” (Good and Brophy, 1990, pp. 187). Set within cognitive information process theory, the collective mind is seen as an information system that operates through a set of logical mental rules, and strategies (e.g., Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968; Bowlby, 1980; Novak, 1993; Wang, 2007).

In this paper we adopt a theoretical approach intended to represent the personality through a set of traits, and we develop Mindset theory as a means by which normative personalities can be assessed. Mindset theory is a derivative of Mindscape theory, a little known approach for reasons that likely include its lack of generative transparency. In order to correct this we will create Mindset theory by adopting the cybernetic trait model of Yolles, Fink & Dauber (2011). Then, to facilitate assessment we connect this with the extensive empirical study by Shalom Schwartz (e.g., Sagiv-Schwarz, 2007) on epistemic cultural values. In particular we shall show that normative personalities can take Mindscape types which can be transparently generated from combinations of bi-polar traits that arise from Sagiv-Schwartz theory.

Having referred to traits, it is useful to consider something more about them. A trait is usually seen as a distinguishing feature, characteristic or quality of a personality style. It creates a predisposition for a personality to respond in a particular way to a broad range of situations (Allport, 1961). Traits are also described as enduring patterns of perceiving, relating to, and thinking about the environment and oneself that are exhibited in a wide range of social and personal contexts. They constitute habitual patterns of thought, emotion and stable clusters of behaviour. They are therefore better seen as constructs that reflect different sets of values and attitudes. There may be a variety of traits, but we can also identify super-traits (Bandura, 1999) or global traits (Van Egeren, 2009) which play a formative role in the development of personality. These formative traits are constituted as self-regulatory propensities or styles that affect how individuals characteristically pursue their goals (Van Egeren, 2009). In this paper when we refer to traits, we shall mean formative traits. These operate as continuous variables that together are indicative of personality, and are subject to small degrees of continuous variation. Traits may take scalar values that for Eysenck (1957) determine personality type. As an illustration, the Five Factor Method (FFM1 or the Big Five) is an empirically based classificatory trait approach where the traits take on single pole and bi-polar values (Cattel, 1945; Goldberg, 1993; Costa & McCrae 1992).

Normally, type theory is useful in personality assessment since they represent conditions of a personality that can be associated with a set of characteristics or properties that establish a penchant towards certain patterns of behaviour. There are schemas (models that may or may not be developed into or be connected with full theories) that explore types, though sometimes as in the MBTI (Myers, 2000) schema the traits are inferred as existing virtually, and unspecified. While explicitly defined traits take on identifiable personality control functions, virtual traits also take on control functions, but in this case they would be implicit and unidentified (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990).

While traits constitute useful variables for the characterisation of personality, there is some confusion in the literature in the way that types are defined. Some authors (e.g. Eysenck, 1957) find that simple distinguishing marks may qualify single traits as types, while Myers-Briggs when referring to types means meta-types, i.e. a determinable collection of types (Myers, 2000). Following Eysenck, types can be defined through a trait that can characterize a system. If more than a single trait is needed to characterize a system, then types may occur as some composite of several traits with certain distinguishing marks. Thus for instance consider the case of the extreme poles of bi-polar traits. The number of types (z) to be generated from bi-polar traits depends on the number of traits (n) that constitute a system: z = 2n. In a case where three states of a trait (e.g., the extremes and a range in the middle) constitute a system, then z = 3n. We have already referred to MBTI as a “personality type” approach with virtual traits, and which operates as a classificatory system that was created from Jung’s (1923) bi-polar temperament personality theory. From 4 bi-polar virtual traits, a system of 16 personality types was created by Myers-Briggs (Myers & McCaulley, 1985; Myers, McCaulley, Quenk & Hammer, 1998).

While personality traits create a potential for the generation of descriptive clusters of behaviour, many consider them to represent the ultimate causes of patterns of behaviour. However, if such a view is to be sustainable, then additional theory is needed that ties trait schemas that simply classify personalities to one type or another, to dynamic schemas that involve causative processes and allow for personality shifts, as for instance through: (a) Piaget’s (1950) concepts of child development and Bandura’s (2006) psychology of the human agency that would allow traits to take a role that is significantly beyond their use as classification systems; and (b) Piaget’s ideas of intelligent behaviour and Bandura’s interest in efficacy and performance that establish ideas of change in behaviour through learning that existing trait theories are unable to currently represent. It may be possible for trait theory to embrace such concepts by seeing them as enduring patterns of cognitive schemas that arise from such phenomena as perceiving, relating to, and thinking about the environment and oneself, i.e., they condition decision making processes in some way. Action then emerges from the major processes of cognition, motivation, affect, effectiveness recognition, and selection of available patterns of behaviour.

In contrast to MBTI, Maruyama developed his socio-cognitive personality type theory through a schema of epistemological meta-types, which he called Mindscape theory. This schema permits personal determinants to operate dynamically within causal structures. Meta-types are combinations of epistemic values (which we call enantiomers) which are constituted as elements of human culture, material objects, or human practice (Maruyama, 1988). Mindscape analysis, Maruyama claims, is particularly suitable for complex and multifaceted environments, and can be used to explore the interrelations among seemingly unrelated aspects of human activities. While Mindscape theory is represented as an epistemological typology, its purpose and use lie in interrelating seemingly separate aspects of human activities (Maruyama, 1988, p.311). While Mindscape modes are numerous and vary from individual to individual, they cumulate into at least four common and stable types that may be partly innate and partly learned.

Social collectives have a normative collective cognitive ability (Thompson, Leigh and Gary Alan Fine, 1999), and as such they also have what we shall call a normative personality - a principle also supported by, for instance, Bridges (1992), Kets de Vries (1991) and Yolles (2006), and already implicitly embedded in Mindscape theory and MBTI. Hence, Mindscape theory can apply to social personality and individual personality contexts. Within the context of the social personality "one of the [personality] types becomes powerful for historical or political reasons, and utilizes, ignores or suppresses individuals of other types" (Maruyama, 2002, p167; cited by Boje, 2004). Following Maruyama (1988; 2001; 2008) and Boje (2004), four types of Mindscapes always exist in any culture, though their percentage distribution varies across cultures3. Available data on cross-cultural migrants indicate that some aspects of Mindscapes are formative in childhood and become irreversible at the age of around ten, approximately corresponding to the child’s formative years. An agency with one Mindscape mode may "learn" to "understand" by some intellectual process a figurative structure that is conceptualized in other Mindscapes, but the results of such attempts are likely to be highly distorted or psychologically artificial. This becomes clearer, for example, when an agency is a human activity group that holds a particular paradigm in science (Kuhn, 1970).

Gammack (2002), in his discussion of Mindscape theory, noted Maruyama’s rejection of the common simple-minded typologies in favour of a “relationology” that goes further than temperamental classifications of individual qualities. Rather it specifies an epistemological basis from which communicative and behavioural styles result. Cultures are seen to be epistemologically heterogeneous, and a number of canonical Mindscape modes exist that are each represented within them in some proportion. These epistemological modes are seen to be prior to, and transcendent of, nationality and culture (Maruyama, 1988; 2001). Indeed, as indicated by Maruyama (1974) these epistemological types are directly related to personality characteristics and cultural backgrounds. An epistemic description of each of these Mindscapes has been proposed by Dockens (2004) (adapted from Maruyama, 1980) as shown in Table 2. Here the epistemic categories cover, for Dockens, a typology of knowledge that constitutes the basis of the Mindscape types. The names given to each of the mindscape types while having there origin in Maruyama (1974), arise from Boje (2004).

Mindscape types were perceived by Maruyama (1988) to be quite different from the Jungian psychological typologies. They provide a link between seemingly separate activities such as decision process, criteria of beauty, and choice of science theories. They do not line up on a single scale, nor do they fit in a two-by-two table. Rather, Maruyama considered, they are more like the four corners of a tetrahedron. Mindscape theory is not a classificational typology (like that of Myers, 2000) since its purpose and use “lie in interrelating seemingly separate aspects of human activities such as organizational structure, policy formulation, decision process, architectural design, criteria of beauty, choice of theories, cosmology, etc.” (Maruyama, 1988:2). Maruyama assumed that it has a relational basis.

Maruyama’s (2002, p167) argument has already been noted that a social system develops an affinity for one personality meta-type over another for historical or political reasons, and ignores or suppresses individuals of other types. This perception is in contrast to Jung (1923), Schwartz (1990) and to Tamis-LeMonda et al (2007). Maruyama settles on the ‘opposing view’ perception of alternate poles.

Using Mindscape theory provides a broad and potentially dynamic capacity to describe agencies, and thereby can generate explanations about situations in which they were involved, or expectations about their potential behaviour in anticipated situations.

Creating Eight Mindset Types from the Sagiv-Schwartz Trait Basis

Following an interest in characterising societal culture, Schwartz (1999, 2004) undertook an extensive study (60,000 respondents) to explore the dimensionality of cultural orientations. It derived cultural orientations from a priori theorizing (unlike previous approaches such as: Hofstede, 1980, 2001; House, Javidan, & Dorfman, 2001; Inglehart & Baker, 2000) rather than post hoc examination of data. The measuring instrument Schwartz used a designated set of a priori value items to serve as markers for each orientation. These items were tested for cross-cultural equivalence of meaning. The items were demonstrated to cover the range of values recognized cross-culturally. In addition, it specified how the cultural orientations are organized into a coherent system of related dimensions and verified this organization, rather than assuming that orthogonal dimensions best capture cultural reality. Finally, it brought empirical evidence that the order of national cultures on each of the orientations is robust across different types of samples from many countries around the world.

Sagiv and Schwartz (2007) identified three bipolar dimensions of culture that represent alternate resolutions to each of three challenges that confront all societies. In the context of the agency, these bipolar dimensions constitute enantiomer pairs that (like Boje’s (2004) conceptions where he formulated a set of Foucaultian based traits to create a Mindscape space) can be assigned to some originating trait, the names of which have been influenced by Piaget’s (1950) theory of human commonalities. These traits with paired enantiomers are: cognitive (embeddedness, autonomy), figurative (hierarchy, egalitarianism) and operative (mastery, harmony). These are explained briefly in Table 3.

(1) Cognitive Trait Enantiomers

Embedded cultures are consistent with a collectivistic view, where meaning in life can be found largely through social relationships, identifying with the group, participating in a shared way of life, and the adoption of shared goals. Values like social order, respect for tradition, security, and wisdom are important. There tends to be a conservative attitude in that support is provided for the status quo and restraining actions against inclinations towards the possible disruption of in-group solidarity or the traditional order.

Autonomy cultures are consistent with an individualistic view, where meaning is found in the uniqueness of the individual that is encouraged to express internal attributes (preferences, traits, feelings, motives). Two classes of cultural autonomy arise: Intellectual and Affective Autonomy. Intellectual autonomy presumes that individuals are encouraged to pursue their own ideas and intellectual directions independently (important values: curiosity, broadmindedness, creativity), while in affective autonomy individuals are encouraged to pursue affectively positive experience for themselves. The values are: exciting life, enjoying live, varied life, pleasure, and self-indulgence. At this point it is important to note that there are notable reasons why Shalom Schwartz has kept affective autonomy separately from intellectual autonomy. Affective autonomy is also positively correlated with Mastery, and it is granting that those who achieve high efficacy through mastery also can enjoy the benefits of their efforts. These two facets of the enantiomer constitute an important element of individualism and are in contrast to harmony.

(2) Figurative Trait Enantiomers

Mastery promotes the view that active self-assertion is needed in order to master, direct, and change the natural and social environment to attain group or personal goals (values: ambition, success, daring, competence). Mastery organizations tend to be dynamic, competitive, and oriented to achievement and success, and are likely to develop and use technology to manipulate and change the environment to achieve goals.

Harmony promotes the view that the world should be accepted as it is, with attempts to understand and appreciate rather than to change, direct, or exploit. There is an emphasis on fitting harmoniously into the environment (values: unity with nature, protecting the environment, world at peace). In harmony organisations, there is an expectation that they will fit into the surrounding social and natural world. Leaders that adopt this type try to understand the social and environmental implications of organizational actions, and seek non-exploitative ways to work toward their goals.

(3) Operative Trait Enantiomers

Hierarchy supports the ascription of roles for individuals to ensure responsible, productive behavior. Unequal distribution of power, roles, and resources are seen to be legitimate (values: social power, authority, humility, wealth). The hierarchical distribution of roles is taken for granted and to comply with the obligations and rules attached to their roles.

Egalitarianism promotes the view that people recognize one another as moral equals who share basic interests. There is an internalisation of a commitment towards cooperation, and to feelings of concern for everyone's welfare. There is an expectation that people will act for the benefit of others as a matter of choice (values: equality, social justice, responsibility, honesty).

These traits and their enantiomer characteristics are summarised in Table 3 together with a listing of keywords that are relevant to the types. Setting the cultural-level Sagiv-Schwartz enantiomers into a trait space thereby enables the generation of what we call a set of Sagiv-Schwartz Mindset Types (Table 5). As explained earlier, while they come from a similar frame of reference to that of Maruyama, their epistemology arises differently.

For the formation of Sagiv-Schwartz Mindset Types we use the Schwartz (1994) set of values and formation of value dimensions (Table 3). Using the same epistemic mapping technique as adopted by Maruyama to compare his Mindscapes with Harvey, we compared the Maruyama constructs with those derived from Sagiv and Schwartz (2007). For Sagiv-Schwartz Mindset Types, we have found better comparability with the Maruyama Mindscape types when, from the Schwartz value inventory, we closely relate ‘affective autonomy’ to ‘mastery’ and form a composite epistemic bi-polar trait (Mastery & Affective Autonomy vs. Harmony).

When comparing the values and attitudes of the Maruyama Mindscape types with the Sagiv & Schwartz value dimensions in an epistemological mapping, we easily find values/items of the Schwartz universe which fit part of the respective Maruyama Mindscape types as shown below.

The H type contains numerous items which are similar or can be related to notions of embeddedness and hierarchy of the Schwartz system: hierarchical, homogenist (conventionalist), classification (neat categories), universalist, sequential, competitive, one truth, eternal, unity by similarity, ethics to dominate the weak, ingroup, self-stereotyping, group bounded, prone to collectivism.

The I type contains numerous items which are similar or can be related to notions of intellectual autonomy, affective autonomy and mastery of the Schwartz system: independent, heterogenistic, unconventionalist, individualistic, uniqueness, separation, caprice, subjectivity, isolationist, temporary, no order, identity, specialization, indifference, poverty self-inflicted, prone to individualism.

As a reflection of the ‘mutualists Mindscape types’ mentioned previously and arising from Maruyama (1974), we find similarities to the notions egalitarianism and harmony of the Schwartz system: heterogenistic, interactive, mutualizing, relating, simultaneous, positive-sum, poly-ocularity, absorption, contextual, non-hierarchical. The consequent differentiation between the G type and the S type apparently is influenced by a slightly stronger orientation towards intellectual autonomy of the G type and towards embeddedness of the S type. Considering the Schwartz value universe (Figure 1) which was produced with the Co-Plot [4] technique of Raveh (2000), we find that Maruyama intuitively discovered that neighbouring ‘value fields’, i.e. combinations of positively correlated values, form the basis of emergent behavioural types. In terms of the Schwartz value universe: ‘hierarchists’ have a preference for hierarchy and embeddeness, ‘indivudualists’ have a preference for autonomy and mastery, and ‘mutualists’ have a preference for egalitarianism and harmony.

Now, we can note that the route suggested by Boje (2004) can be further pursued with a more differentiated system of 8 types derived from Sagiv-Schwartz (2007) traits. To do this we initially formulate a labelling code as shown in Table 4. These arise from epistemic cross-comparison deriving from the traits poles (the enantiomers), and permit choices to be made for labels from the options available.

As a result we can formulate the Mindset types against the enantiomers and their epistemic values as shown in Table 5. The type numbers do not imply trait importance, but simply are counting the number of types.

Graphically, the relations between the eight Mindset cognitive types shown in the Mindset Space of Figure 2 are extreme types. Four pairs of Mindset types can be seen that are in diametric contrast. However, the 8 types can be multiplied since balances between the types can also develop, which is something that we shall return to in due course. Four of these eight Mindset Types correspond to the four Maryuama Mindscape Types. With this it is possible to fill a gap indicated by Boje (2004) and identify four additional Mindset Types.

For further analysis beyond contrasting Mindset types, where all three alternate enantiomer poles are different, we may also take a look at variation, where two enantiomers are the same and only one is varied. In the Sagiv-Schwartz value universe six options arise, which are presented in Table 7. We begin with Harmony and move clockwise around the Schwartz value universe (Figure 1). We present variations, where two central pairs of constructs are kept constant. In the Sagiv-Schwartz universe these pairs are located next to each other, because these constructs are correlated to each other.

Now, one remaining open issue is whether the number of types is appropriate to characterize variety within and between social systems? Apparently, any number of types could be created from any number of traits. Once, in an interview Geert Hofstede said to one of the authors: “Values - you can have as many as you want. The issue is, whether you have a sufficiently large number, for differentiation, and a sufficiently small number to be remembered by the audience.” The number of traits quickly increases when several states of a trait are considered to be type forming. In Figure 2 we illustrate 8 types which emerge from the alternate poles of 3 traits: 8=23. In a case where three states of a trait (e.g. the extremes and a range in the middle) constitute a system, then z=3n. E.g. one could assume that the upper and lower third of a trait represent the two poles of a trait, and the middle third represents a balanced attitude. In that case we would end up with 27 possible types: 27=33.

Tuesday, August 27, 2013

The Mindset List for the Class of 2017 (Beloit College)

Each year as the new crop of college freshmen leave their families and begin the journey into adulthood, Beloit College reminds the rest of us how we are by offering a list of perspectives held by this particular group of freshmen.

Sadly, the gender balance in the image above is also indicative of the the new freshman class in most schools - young women outnumber young men by as much as 2:1.

It's somewhat amusing, to me at least, that Beloit offers this list with the assumption these kids will finish school in four years. While that may be true at Beloit, most freshman entering college this year will take more than four years, and as many as six (or more).

2017 List

When the Class of 2017 arrives on campus this fall, these digital natives will already be well-connected to each other. They are more likely to have borrowed money for college than their Boomer parents were, and while their parents foresee four years of school, the students are pretty sure it will be longer than that. Members of this year’s first year class, most of them born in 1995, will search for the academic majors reported to lead to good-paying jobs, and most of them will take a few courses taught at a distant university by a professor they will never meet.

The use of smart phones in class may indicate they are reading the assignment they should have read last night, or they may be recording every minute of their college experience…or they may be texting the person next to them. If they are admirers of Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, they may wonder whether a college degree is all it’s cracked up to be, even as their dreams are tempered by the reality that tech geniuses come along about as often as Halley’s Comet, which they will not glimpse until they reach what we currently consider “retirement age.”

Though they have never had the chicken pox, they are glad to have access to health insurance for a few more years. They will study hard, learn a good deal more, teach their professors quite a lot, and realize eventually that they will soon be in power. After all, by the time they hit their thirties, four out of ten voters will be of their generation. Whatever their employers may think of them, politicians will be paying close attention.

Each August since 1998, Beloit College has released the Beloit College Mindset List, providing a look at the cultural touchstones that shape the lives of students entering college this fall. Prepared by Beloit’s former Public Affairs Director Ron Nief and Keefer Professor of the Humanities Tom McBride, the list was originally created as a reminder to faculty to be aware of dated references. It quickly became an internationally monitored catalog of the changing worldview of each new college generation. Mindset List websites at themindsetlist.com and beloit.edu, as well as the Mediasite webcast and their Facebook page receive more than a million visits annually.

The Mindset List for the Class of 2017

For this generation of entering college students, born in 1995, Dean Martin, Mickey Mantle, and Jerry Garcia have always been dead.

1. Eminem and LL Cool J could show up at parents’ weekend.

2. They are the sharing generation, having shown tendencies to share everything, including possessions, no matter how personal.

3. GM means food that is Genetically Modified.

4. As they started to crawl, so did the news across the bottom of the television screen.

5. “Dude” has never had a negative tone.

6. As their parents held them as infants, they may have wondered whether it was the baby or Windows 95 that had them more excited.

7. As kids they may well have seen Chicken Run but probably never got chicken pox.

8. Having a chat has seldom involved talking.

9. Gaga has never been baby talk.

10. They could always get rid of their outdated toys on eBay.

11. They have known only two presidents.

12. Their TV screens keep getting smaller as their parents’ screens grow ever larger.

13. PayPal has replaced a pen pal as a best friend on line.

14. Rites of passage have more to do with having their own cell phone and Skype accounts than with getting a driver’s license and car.

15. The U.S. has always been trying to figure out which side to back in Middle East conflicts.

16. A tablet is no longer something you take in the morning.

17. Threatening to shut down the government during Federal budget negotiations has always been an anticipated tactic.

18. Growing up with the family dog, one of them has worn an electronic collar, while the other has toted an electronic lifeline.

19. Plasma has never been just a bodily fluid.

20. The Pentagon and Congress have always been shocked, absolutely shocked, by reports of sexual harassment and assault in the military.

21. Spray paint has never been legally sold in Chicago.

22. Captain Janeway has always taken the USS Voyager where no woman or man has ever gone before.

23. While they've grown up with a World Trade Organization, they have never known an Interstate Commerce Commission.

24. Courts have always been ordering computer network wiretaps.

25. Planes have never landed at Stapleton Airport in Denver.

26. Jurassic Park has always had rides and snack bars, not free-range triceratops and velociraptors.

27. Thanks to Megan's Law and Amber Alerts, parents have always had community support in keeping children safe.

28. With GPS, they have never needed directions to get someplace, just an address.

29. Java has never been just a cup of coffee.

30. Americans and Russians have always cooperated better in orbit than on earth.

31. Olympic fever has always erupted every two years.

32. Their parents have always bemoaned the passing of precocious little Calvin and sarcastic stuffy Hobbes.

33. In their first 18 years, they have watched the rise and fall of Tiger Woods and Alex Rodriguez.

34. Yahoo has always been looking over its shoulder for the rise of "Yet Another Hierarchical Officious Oracle.”

35. Congress has always been burdened by the requirement that they comply with the anti-discrimination and safety laws they passed for everybody else to follow.

36. The U.S. has always imposed economic sanctions against Iran.

37. The Celestine Prophecy has always been bringing forth a new age of spiritual insights.

38. Smokers in California have always been searching for their special areas, which have been harder to find each year.

39. They aren’t surprised to learn that the position of Top Spook at the CIA is an equal opportunity post.

40. They have never attended a concert in a smoke-filled arena.

41. As they slept safely in their cribs, the Oklahoma City bomber and the Unabomber were doing their deadly work.

42. There has never been a national maximum speed on U.S. highways.

43. Don Shula has always been a fine steak house.

44. Their favorite feature films have always been largely, if not totally, computer generated.

45. They have never really needed to go to their friend’s house so they could study together.

46. They have never seen the Bruins at Boston Garden, the Trailblazers at Memorial Coliseum, the Supersonics in Key Arena, or the Canucks at the Pacific Coliseum.

47. Dayton, Ohio, has always been critical to international peace accords.

48. Kevin Bacon has always maintained six degrees of separation in the cinematic universe.

49. They may have been introduced to video games with a new Sony PlayStation left in their cribs by their moms.

50. A Wiki has always been a cooperative web application rather than a shuttle bus in Hawaii.

51. The Canadian Football League Stallions have always sung Alouette in Montreal after bidding adieu to Baltimore.

52. They have always been able to plug into USB ports

53. Olestra has always had consumers worried about side effects.

54. Washington, D.C., tour buses have never been able to drive in front of the White House.

55. Being selected by Oprah’s Book Club has always read “success.”

56. There has never been a Barings Bank in England.

57. Their parents’ car CD player is soooooo ancient and embarrassing.

58. New York’s Times Square has always had a splash of the Magic Kingdom in it.

59. Bill Maher has always been politically incorrect.

60. They have always known that there are “five hundred, twenty five thousand, six hundred minutes" in a year.

Thursday, August 15, 2013

John Horgan's Postmodern Response to Steven Pinker’s Patronizing “Plea” for Scientism

In his Cross Check column for Scientific American, John Horgan offers his response to Steven Pinker's recent New Republic essay, Science is Not Your Enemy (the article and my comments are here).

Here is a key passage from Horgan's "postmodern response":

Pinker’s idea of engagement seems to be kowtowing to science’s awesomeness. We already have too many prominent Humists serving as shills for science. Take, for example, the philosophers Daniel Dennett and Patricia Churchland, who seem to think that MRI maps of brains are solving the mind-body problem.

Pinker himself grossly overvalues the contributions of fields such as evolutionary psychology, behavioral genetics and neuroscience to our modern understanding of ourselves. And he has insulted the philosopher Thomas Nagel for daring to question whether science in its current form can account for the mysteries of life and consciousness.I am in total agreement with this assessment - and with Horgan's rejection of scientism:

Attempting rhetorical jujitsu, Pinker suggests that science, because it is such a uniquely self-critical and successful generator of knowledge, deserves all our trust. Hence scientism is justified and we should all embrace it!Perhaps a better definition of scientism (than Horgan's "excessive trust in science") would be an inability to see perspectives outside of the scientific method as having any validity. Scientism is the view that only science can offer us truth and moral guidance - and Pinker seems to be its biggest cheerleader.

Should the Humanities Embrace Scientism? My Postmodern Response to Pinker’s Patronizing “Plea”

By John Horgan | August 14, 2013

Damn you, Gary Stix! I was just about to head off on a vacation when my old Scientific American buddy sent me an email command: “Attack, John!” Gary’s email linked to a New Republic essay by Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker: “Science is Not Your Enemy,” snidely subtitled, “An impassioned plea to neglected novelists, embattled professors, and tenure-less historians.”

Psychologist Steven Pinker says humanities scholars should be "delighted" by science's intrusion on their turf.

I like and respect Pinker. But a more accurate title for his condescending essay would have been, “Kicking the Humanities When They’re Down.”

He harangues humanities folks—whom I’ll call Humists–for resenting science’s increasing intrusion into their intellectual territory. According to Pinker, Humists should be “delighted and energized by the efflorescence of new ideas from the sciences,” which have become “indispensable in all areas of human concern, including politics, the arts, and the search for meaning, purpose, and morality.”

Pinker faults Humists for accusing scientists of “scientism,” which could be defined as excessive trust in science. Attempting rhetorical jujitsu, Pinker suggests that science, because it is such a uniquely self-critical and successful generator of knowledge, deserves all our trust. Hence scientism is justified and we should all embrace it!

Now, before I knock Pinker further, let me acknowledge where our views overlap. First, we both believe in the attainability of truth and progress, and we agree that science is by far our most powerful means of understanding and improving our world.

I also get annoyed, like Pinker, when Humists dismiss science out of sheer ignorance. If you want to be taken seriously as an intellectual these days, you should engage with science, including pure and applied science, engineering, medicine and so on. And to engage with science, you should know something about it.

But Pinker’s idea of engagement seems to be kowtowing to science’s awesomeness. We already have too many prominent Humists serving as shills for science. Take, for example, the philosophers Daniel Dennett and Patricia Churchland, who seem to think that MRI maps of brains are solving the mind-body problem.

Pinker himself grossly overvalues the contributions of fields such as evolutionary psychology, behavioral genetics and neuroscience to our modern understanding of ourselves. And he has insulted the philosopher Thomas Nagel for daring to question whether science in its current form can account for the mysteries of life and consciousness.

So my advice to Humists is this: By all means engage with science, but engage with it critically, because science—contrary to what Pinker suggests–badly needs tough, informed criticism. As I said in a recent column, “it is precisely because science is so powerful that we need the humanities now more than ever.”

Here’s a more specific suggestion: Just as Pinker proudly, perversely, embraces “scientism,” Humists should embrace the much-maligned term “postmodernism.” Pinker, of course, loathes postmodernism. “The humanities,” he writes, “have yet to recover from the disaster of postmodernism, with its defiant obscurantism, dogmatic relativism, and suffocating political correctness.”

Pinker never seems to have understood postmodernism. Postmodern scholarship, like science itself, can be done well or badly, but its animating assumption is simple: All truth claims–whether scientific, religious or political—reflect the prejudices and desires of those who make them. Claims that become dominant in a culture often serve the interests of powerful groups.

Social Darwinism and eugenics are two especially egregious examples of pseudo-scientific ideologies that reflected the racism, sexism and classism of proponents. Pinker depicts Social Darwinism and eugenics as historical aberrations that had little or nothing to do with science–even though their central claims keep reappearing in modern scientific trappings.

Moreover, even a casual survey of modern science—and of this blog–reveals the degree to which science continues to serve the interests of powerful groups. The U.S. health care industry delivers lousy service at exorbitant prices, arguably because it ismore concerned with profits than with patients. Modern psychiatry has become little more than a marketing branch of the pharmaceutical industry.

Neuroscience, psychology, artificial intelligence and other fields are increasingly dependent on military funding. Pinker himself has popularized the hypothesis that war is an instinct, rooted deeply in our evolutionary past, which civilization has helped us overcome. This notion serves as a convenient justification for modern U.S. militarism and imperialism.

Postmodernism is, in a sense, simply another expression of a truism of science journalism: If you want to understand modern debates about climate, energy, genetically modified food, economic equality or military policies, you should follow the money. Money certainly doesn’t explain everything—and just because a group is rich and powerful doesn’t mean that it’s corrupt–but it explains a lot.

It’s probably obvious by now that I’m really asking Humists to become more like science journalists, especially those who view science skeptically. Like the humanities, science journalism is struggling these days, and we need all the help we can get in providing critical evaluations of science. Together, Humists and science journalists can serve as science’s loyal opposition, pointing out how far science often falls short of the idealized portrayals peddled by flakes like Pinker.

Okay, now I’m going to forget about scientism and postmodernism and go for a run on a beach. And Gary, no more emails!

Photo of Pinker speaking at TED Conference: http://www.ted.com.

About the Author: Every week, hockey-playing science writer John Horgan takes a puckish, provocative look at breaking science. A teacher at Stevens Institute of Technology, Horgan is the author of four books, including The End of Science (Addison Wesley, 1996) and The End of War (McSweeney's, 2012). Follow on Twitter @Horganism.

Monday, August 12, 2013

Marcus Feldman - Cultural Contingency and Gene-Culture Coevolution

This is a very interesting and informative talk (the parts I fully grasped, anyway) about the interplay between genes and culture in human evolution. Marcus Feldman (Wohlford Professor of Biological Sciences, Director of the Morrison Institute for Population and Resource Studies, Stanford University) was one of the pioneering population geneticists in the study of gene-culture coevolution, going back to 1973.

His specific areas of research include the evolution of complex genetic systems that can undergo both natural selection and recombination, and the evolution of learning as one interface between modern methods in artificial intelligence and models of biological processes, including communication. He also studies the evolution of modern humans using models for the dynamics of molecular polymorphisms, especially DNA variants. He helped develop the quantitative theory of cultural evolution, which he applies to issues in human behavior, and also the theory of niche construction, which has wide applications in ecology and evolutionary analysis.Here is a link to a 1985 paper on gene-culture coevolution: Gene-culture coevolution: Models for the evolution of altruism with cultural transmission (w/ L L Cavalli-Sforza, and J R Peck. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), Vol. 82(17), pp. 5814-5818, September 1985; Evolution)

Cultural Contingency and Gene - Culture Coevolution

Published on Jul 22, 2013

Speaker: Marc Feldman, Stanford University, SFI Science Board

Response: Henry Wright, University of Michigan, SFI Science Board

May 3, 2013

New Perspectives in Evolution - Symposium

May 02, 2013 - May 04, 2013

Santa Fe, NM

This annual SFI Science Board meeting will focus on building a vision for future SFI research directions. The topic this year focuses on new quantitative, biological, and cultural perspectives on evolution.

Click here to download the agenda.

Thursday, June 20, 2013

Lexi Neale - The AQAL Cube for Dummies

In the current Integral Leadership Review, Lexi Neale was finally persuaded by Russ (Volckmann, owner and founder of the Review) to write a dumbed-down version of his AQAL Cube theory for the ILR.

It's a long article and very much worth your time to read. For the purposes of this post, I am only including the author's note at the beginning and the 2nd major section of the paper, on how the cube relates to individual human beings. I can see a potential use for this in Integral Psychotherapy.

I'm not a huge fan of the "quantum consciousness" piece (locality and nonlocality) he adds to the model, especially in light of using the Hameroff/Penrose model. Their theory is speculative at best, and simply wrong in the minds of many cognitive neuroscientists and quantum physicists.

About the Author

Lexi Neale has a varied background. He studied Zoology and Psychology in 1966-1969, B.Sc. , London University. In 1971 in Glastonbury he met his thirteen-year-old Master, Prem Rawat, just arrived from India. Prem Rawat teaches a time-honored integral practice that he calls Knowledge of the Self – as in Know the Knower. Lexi Neale is affiliated with The Prem Rawat Foundation, an award-winning charity providing aid for the relief of human suffering. Contact www.tprf.org and wordsofpeaceglobal.org (wopg.org). He is also a member of the Integral Research Center as an Integral Theorist. Contact Lexi Neale personally at lexneale.integral@gmail.com

It's a long article and very much worth your time to read. For the purposes of this post, I am only including the author's note at the beginning and the 2nd major section of the paper, on how the cube relates to individual human beings. I can see a potential use for this in Integral Psychotherapy.

I'm not a huge fan of the "quantum consciousness" piece (locality and nonlocality) he adds to the model, especially in light of using the Hameroff/Penrose model. Their theory is speculative at best, and simply wrong in the minds of many cognitive neuroscientists and quantum physicists.

About the Author

Lexi Neale has a varied background. He studied Zoology and Psychology in 1966-1969, B.Sc. , London University. In 1971 in Glastonbury he met his thirteen-year-old Master, Prem Rawat, just arrived from India. Prem Rawat teaches a time-honored integral practice that he calls Knowledge of the Self – as in Know the Knower. Lexi Neale is affiliated with The Prem Rawat Foundation, an award-winning charity providing aid for the relief of human suffering. Contact www.tprf.org and wordsofpeaceglobal.org (wopg.org). He is also a member of the Integral Research Center as an Integral Theorist. Contact Lexi Neale personally at lexneale.integral@gmail.com

The AQAL Cube for Dummies

Lexi Neale

Download article as PDF

Lexi Neale

Author’s Note: The above title is not intended to be demeaning, dear Reader, but more of an inside joke between Russ and I. Russ has twice approached me about an AQAL Cube article, and has twice shied away from what I sent him. His complaint? Too complex! So I have finally relented and taken his observation to heart. I sincerely hope that the following extension of Ken Wilber’s AQAL Square model is at least comprehensible, if not acceptable!

Since Ken introduced my AQAL Cube extension of his Integral model, the AQAL Square, on kenwilber.com, archived June 12th 2009, it has been “the best of times, and the worst of times” (A Tale of Two Cities) as in a tale of two models. In an introduction he wrote for Part 2, archived November 4th 2009, where I pitched the AQAL Cube as Wilber-6, he said “In my mind, of course, it is definitely not Wilber-6, just a thoughtful extension of Wilber-5.” And in my mind, of course, I am still challenging that!

It is true that the AQAL Cube vastly complicates the Integral model by introducing AQAL Non-locality into the mix, and also the liberal notion of Eight Fundamental Perspectives PER PERSON, but the complication has more to do with the effort of having to transcend/include establishment Integral concepts rather than complexity per se. I let you be the judge of that. Going back to Ken’s comment “a thoughtful extension of Wilber-5”, I decided that should be my guide in writing this article, by keeping to the aspects of the AQAL Cube that truly are extensions of the AQAL Square.

* * * * *

The AQAL Cube per Person

Now we go deeper into our Self-system. Ken’s AQAL Square affords the Self-system two First Person Quadrants (Upper and Lower Left). Ken himself has said that the AQAL Square is really a Third Person model describing First, Second and Third Person phenomena. We now reconsider that blatant admission of flat-land. This is where established Integral Theory gets taken for a really wild ride in a very powerful car!

Remembering how Ken’s Third Person “Inside”’, “Outside”, “Individual”, “Collective”, “Interior” and “Exterior” perspectives recombine to produce the Eight Fundamental Perspectives (Fig. 1), the same logic can be applied to our First Person: As well as our Consciousness Self and our Cognitive Self we also have a Singular Self, a Plural Self, a Subjective Self, and an Objective Self, which recombine in the same way to produce the Eight Fundamental First Person Perspectives. Suddenly our two-cylinder car becomes a V-8!

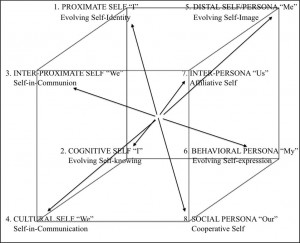

Since the beginning of language the First, Second and Third Person pronouns have defined our self and each other: Me Tarzan, You Jane. And it is in language that we express our intuitive knowledge of our own Self complexity. Fig.2. shows the First Person Cube and its eight First Person pronouns expanding through the Levels.

Figure 2. The First Person Cube

The Quadrants above, 1,3,5,7 are the Non-Possessive Personal Pronouns, and the Quadrants below, 2,4,6,8 are the Possessive Personal Pronouns. The first thing that is apparent is how the Non-Possessive Quadrants 1,3,5 and 7 are intangible First Person identities, and how the Possessive Quadrants 2,4,6 and 8 are tangible First Person experiential attributes of those identities. The differentiation is exactly the same as between Non-Local Consciousness and Local Body-Mind. In other words, our entire cultural history has endorsed the notion of a Four Quadrant “Experiencer-as-Consciousness”, and a correlated Four Quadrant “Experience-as-Mind”.

The second thing we notice about the First Person Cube is that there is no differentiation in English between the two “I’s” and ”We’s” as First Person pronouns in the Subjective Octants 1,2,3 and 4. Language is a two-way street: One the one hand it identifies pre-existing perspectives as a common experience, which then become cultural givens; but on the other hand, in naming them, it can culturally bias some perspectives at the expense of others. Cultures that are objective diminish the subjective; cultures that are collective diminish the individual; cultures that are materialistic diminish the non-material – by not differentiating them. In Russian there is a differentiation between an “inner We” and an “outer collective We” as in “We the people”. In Yiddish there is a differentiation between “I” as a spiritual identity and the “I” of everyday life.

In evaluating his “8 Zones”, Wilber encountered this anomaly himself in differentiating an Inside “I” from an Outside “I”; and an Inside “We” from an Outside “We”. I quote[7]:

‘ – for example, the experience of an “I” in the UL Quadrant. That “I” can be looked at from the inside or the outside. I can experience my own “I” from the inside [Octant 1], in this moment, as the felt experience of being a subject of my present experience, a 1st person having a 1st person experience. If I do so, the results include such things as introspection, meditation, phenomenology, contemplation, and so on (all simply summarized as phenomenology… But I can also approach this “I” from the outside [Octant 2], in the stance of an objective or “scientific” observer. I can so in my own awareness (when I try to be “objective” about myself, or try to “see myself as others see me”) …Likewise, I can approach the study of a “we” from its inside or its outside. From the inside [Octant 3], this includes the attempts that you and I make to understand each other right now. How is it that you and I can reach a mutual understanding about anything, including when we simply talk to each other? How do your “I” and my “I” come together in something you and I both call “we” (as in, “Do you and I – do we – understand each other?”). The art and science of we-interpretation is typically called hermeneutics.‘But I can also attempt to study this “we” from the outside [Octant 4], perhaps as a cultural anthropologist, or an ethnomethodologist, or a Foucauldian archaeologist…And so on around the quadrants. Thus, 8 basic perspectives and 8 basic methodologies.’ (The Octant designations in brackets are mine.)In other words, Wilber completely endorses the Left Octants (1,2,3 and 4) of the First Person AQAL Cube, but he does not extend this argument to the First Person Right Hand Quadrants (5, 6, 7 and 8). He does, however, mention the objective-self issue:

‘If you get a sense of yourself right now – simply notice what it is that you call “you” – you might notice at least two parts to this self: one, there is some sort of observing self (an inner subject or watcher); and two, there is some sort of observed self (some objective things that you can see or know about yourself… The first is experienced as an “I”, the second as a “me”… I call the first the proximate self (since it is closer to “you”), and the second the distal self (since it is objective and “farther away”).’The Proximate and Distal Selves are an Octant 1 and Octant 5 differentiation on the First Person AQAL Cube. Octant 5 is the Distal Self, or the way I formulate my Proximate Self as a Persona in its true etymological sense, as my mask, as how “I” want others to identify with “Me”. This is the All Level “Me” Inside. (Note: This differentiation of the Distal Self or Persona is not the persona of fulcrum 4.) And the correlated behavior of this Persona is “My” personality Outside, where Octant 6 pertains to “My” personality through “My” behavior. The Enneagram as elucidated by Riso[7] makes this differentiation very clearly.

Equally, the Social Persona or our identification with “Us” Inside, and the Social Personality-behavior in “Our” tribe Outside, follow the same First Person differentiations. These eight important First Person Self-differentiations have not yet been made in Integral Psychology, even though they are experientially self-evident to the point where Wilber himself identified six of them, with “Us”.

Integral Theory does in fact obliquely identify the Self-system as a First Person Octo-Dynamic. I noticed how the various Lines of the Self System in the AQAL Square Upper Left have an eerie correspondence with the First Person Eight Fundamental Perspectives. Naturally, this needs to be played out in Integral Research, but I propose that the correspondence self-evidently corroborates the First Person AQAL Cube:

Octant 1: Proximate Self as the Consciousness-as-experiencer “I”. Core self-identity witnessing through Levels of assumed identity states. Lines: Proximate Self-identity, spiritual identity. Representative Levels of Self-identity-as-witness are: Red – Id identity fused with the Lower Mind; Orange – Ego identity fused with the Lower Mind; Blue – Soul Consciousness differentiated from Mind. Violet – Non-Dual Supreme Witness.In the interests of developing a fully Integral model, I suggest that Integral researchers of the Self-system identify their field of research as an Octant in each Person.

Octant 2: Cognitive Self as the “I” Mind. Experiential identity through Fulcrum Levels of intelligence structures. Lines: All Intelligences, such as cognitive, affective, psychosexual, aesthetic, spiritual. Representative Levels of experiential intelligence are: Red – sensing, feeling, emoting; Orange – thinking; Blue – visioning; Violet – wisdom/Akashic experience.

Octant 3: Inter-Proximate Self as “We” Consciousness. Shared self through Levels of assumed identity states. Line: inter-proximate self. Representative Levels are: Red – Inter-Id as fused “I-We”; Orange – Inter-Ego “We”; Blue – Inter-Soul “We”; Violet – Non-Dual “We”.

Octant 4: Cultural Self as the “We” Mind. Interpretive shared or common experience as cultural intelligence. Lines: moral self, worldview self. Representative Levels are: Red – Tribal member (fused “I-We”); Orange – cultural independent; Blue – cultural visionary; Violet – spiritual iconoclast.

Octant 5: Distal Self (Persona) as “Me” Consciousness. Objectively differentiated from the Proximate Self of Octant 1, the Persona is self-referential as a Self-image. This is the intentional persona of the Enneagram, the objective evaluator of the Self-system and home of the Self-judging Super-Ego. After death existence or Bardo is a projection of this self-evaluation as our Non-Local All-Level Persona. Line: intentional persona. Representative Levels as State-stages are: Red – Id-centered, 4th Bardo; Orange – Ego-centered, 3rd Bardo; Blue – Soul-centered, 2nd Bardo; Violet – Pneumo-centered, 1st Bardo.

Octant 6: Behavioral Persona as “My” Mind. Objectively differentiated from the Cognitive Self of Octant 2, the Behavioral Persona is the objective expression of Mind as our Personality and its Enneatypes. Lines: behavioral personalities as applied to cognitive, affective, psychosexual, aesthetic, spiritual. Representative Levels as Structure-stages are: Red – magic; Orange – rational; Blue – integral; Violet – spiritually wise.

Octant 7: Inter-Distal Persona as “Us” Consciousness. The Social Self-image is a fused “Me-Us” until socio-centric, after which the Social Identity differentiates. Identification with family, organizations and affiliations. After-death identification with others is through the correlated Non-Local All-Level Social Persona. Line: interpersonal. Representative Levels as State-stages are: Red – symbiont; Orange – server-dominator; Blue – integrator; Violet – compassionate.

Octant 8: Social Persona as “Our” Mind. The Social Persona evolving as organized and cooperative behavior and experience of social situations. Lines: sociocultural, relational, ethical. Representative Levels as Structure-stages: Red – tribal member; Orange – nationalist; Blue – globalist; Violet – utopian.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)