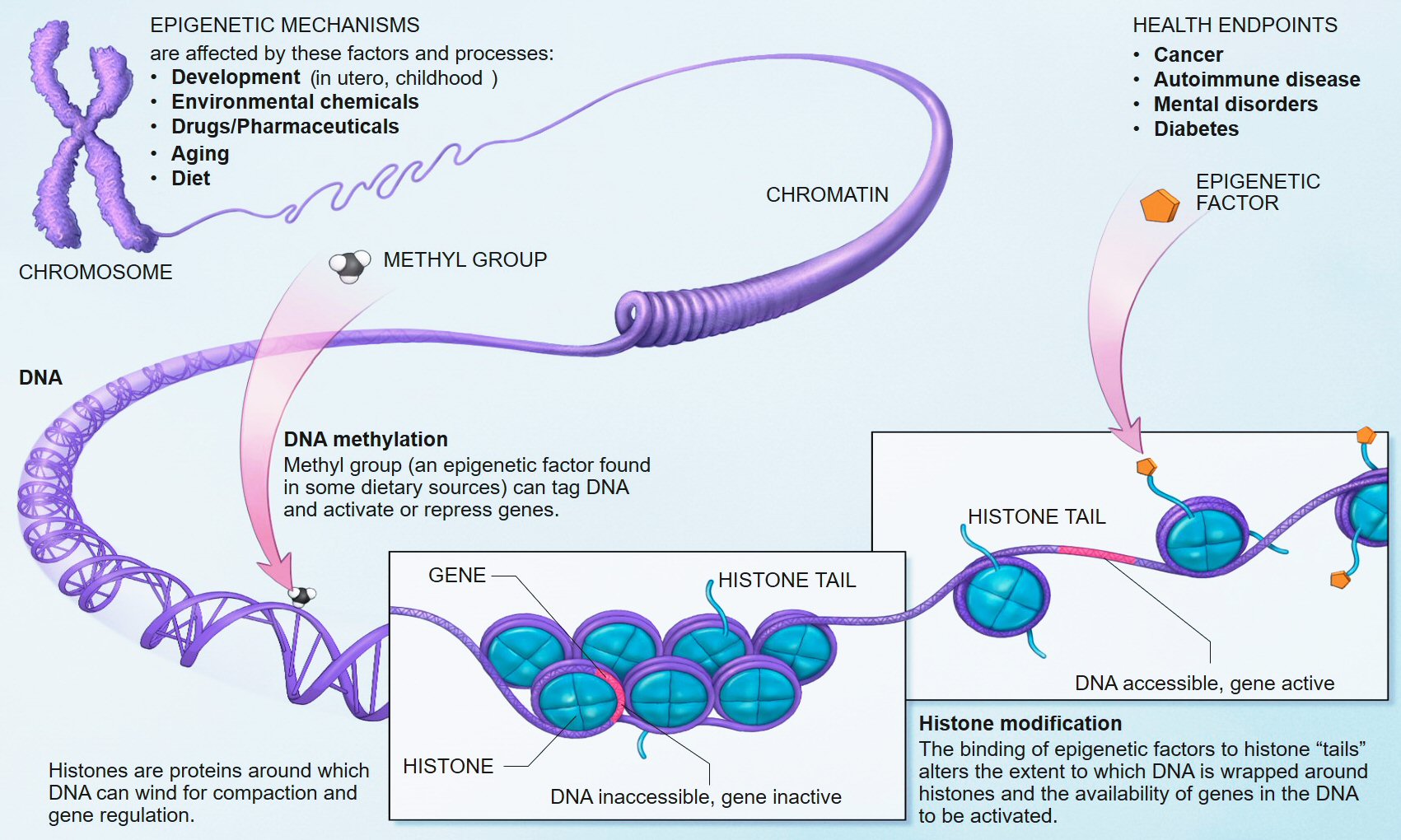

Research in humans has shown that repeated high level activation of the body's stress system, especially in early childhood, can alter methylation processes and lead to changes in the chemistry of the individual's DNA. The chemical changes can disable genes and prevent the brain from properly regulating its response to stress. Researchers and clinicians have drawn a link between this neurochemical dysregulation and the development of chronic health problems such as depression, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and coronary artery disease.[9][10][11][12][13]This new study adds to the evidence of how stress can derail normal developmental processes.

Full Citation:

Khulan, B, Manning, JR, Dunbar, DR, Seckl, JR, Raikkonen, K, Eriksson, JG, and Drake, AJ. (2014, Sep 23). Epigenomic profiling of men exposed to early-life stress reveals DNA methylation differences in association with current mental state. Translational Psychiatry; 4, e448; doi:10.1038/tp.2014.94

Epigenomic profiling of men exposed to early-life stress reveals DNA methylation differences in association with current mental state

B Khulan [1], J R Manning [1], D R Dunbar [1], J R Seckl [1], K Raikkonen [2], J G Eriksson [3,4,5,6,7] and A J Drake [1]

1. Endocrinology Unit, University/BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, Queen's Medical Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

2. Institute of Behavioural Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

3. Department of Chronic Disease Prevention, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland

4. Department of General Practice and Primary Health Care, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

5. Vasa Central Hospital, Vasa, Finland

6. Folkhälsan Research Center, Helsinki, Finland

7. Unit of General Practice, Helsinki University Central Hospital, Helsinki, FinlandAbstract

Early-life stress (ELS) is known to be associated with an increased risk of neuropsychiatric and cardiometabolic disease in later life. One of the potential mechanisms underpinning this is through effects on the epigenome, particularly changes in DNA methylation. Using a well-phenotyped cohort of 83 men from the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study, who experienced ELS in the form of separation from their parents during childhood, and a group of 83 matched controls, we performed a genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation in peripheral blood. We found no differences in DNA methylation between men who were separated from their families and non-separated men; however, we did identify differences in DNA methylation in association with the development of at least mild depressive symptoms over the subsequent 5–10 years. Notably, hypomethylation was identified at a number of genes with roles in brain development and/or function in association with depressive symptoms. Pathway analysis revealed an enrichment of DNA methylation changes in pathways associated with development and morphogenesis, DNA and transcription factor binding and programmed cell death. Our results support the concept that DNA methylation differences may be important in the pathogenesis of psychiatric disease.

Introduction

Early-life stress (ELS) is recognised as a risk factor for later mental health disorders. Findings from a number of studies have linked events in childhood, such as physical or sexual abuse, parental separation, neglect or adoption, with an increased risk of subsequent mental health disorders.1, 2, 3 The long-term adverse effects of ELS are not limited to neuropsychiatric problems and childhood exposure to socioeconomic disadvantage, maltreatment or social isolation is also associated with an increased risk of an adverse cardiometabolic disease risk profile in adulthood.3

Longitudinal cohort studies are an invaluable resource for the study of factors impacting on health, particularly in addressing the long-term impact of ELS. The Helsinki Birth Cohort Study (HBCS), comprising 13 345 individuals born in Helsinki between 1934 and 1944, is one such resource.4 During the Second World War, almost 70 000 Finnish children of varying socioeconomic status were evacuated from their homes to temporary foster families, mainly in the nearby countries of Sweden and Denmark. The evacuations, which occurred between 1939 and 1944, were arranged by the Finnish government or independently by families. Evacuations were voluntary, but heavily promoted by the government and particularly targeted at children living in cities. Documents on the evacuations and their timing and length have been retained in the Finnish National Archives’ Register. Linking evacuation data with the HBCS has allowed the identification of 11 028 individuals within the HBCS who were not separated from their parents as children, and 1719 individuals who were temporarily separated from their parents. The average age at separation was 4.6 years (s.d.=2.4, range=0.17–10.6) and the average length of separation 1.7 years (s.d.=1.6, range=0.05–8.1).

Previous studies in this cohort have identified a number of long-term consequences of early-life separation. Separated individuals have a higher prevalence of mental health disorders including depressive symptoms and personality disorders5 and an increased risk of substance abuse.6 The risk of any mental and substance use disorder was highest among those with an upper childhood socioeconomic background, perhaps suggesting increased vulnerability.6 Separation is also associated with effects on stress biology; separated individuals have higher average salivary cortisol and plasma ACTH concentrations and higher salivary cortisol reactivity to a Trier Social Stress Test.7 In men, separation associates with poorer cognitive performance8 and with negative effects on physical and psychosocial functioning.9 The consequences of separation were not limited to effects on mental health and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, as cohort members who were separated from their parents in childhood also had a higher cardiovascular morbidity, including coronary artery disease, hypertension and type 2 diabetes,10,11 with the highest prevalence of cardiovascular disease in those who were evacuated for the longest period.11 Finally, early-life separation also associated with differences in reproductive and marital traits in both sexes.12

One of the potential mechanisms by which the environment in early life might have a lasting impact on the phenotype of an individual is through effects on the epigenome, particularly changes in DNA methylation13 and consistent with this, a few studies have shown alterations in DNA methylation in association with exposure to ELS.14,15 In this study of a unique cohort of men in their 70s from the HBCS we have investigated the long-term impact of early-life separation on genome-wide DNA methylation and whether this associated with a number of clinical and psychological variables.

Materials and Methods

Cohort

The HBCS comprises 13 345 individuals (6370 women and 6975 men), born as singletons between 1934 and 1944 in one of the two main maternity hospitals in Helsinki and who were living in Finland in 1971 when a unique personal identification number was allocated to each member of the Finnish population. The HBCS, which has been described in detail elsewhere,4 has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Public Health Institute. Register data were linked with permission from the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health and the Finnish National Archives.

In 2001–2004 at an average age of 61.5 years (s.d.=2.9 and range=56.7–69.8 years), a randomly selected subsample of the cohort comprising 2003 individuals (1075 women and 928 men) was invited to a clinical examination including collection of a blood sample for (epi)genetic and biochemical studies and a psychological survey including a measure of depressive symptoms. For 283 participants, extraction of DNA was not successful, or DNA showed gender discrepancy or close relatedness. The excluded and the included participants did not differ from each other in any of the study variables (P-values>0.13). From the remaining sample of 1720 individuals, 115 women and 97 men had been evacuated according to the Finnish National Archives’ register. Of them nine women and 12 men had missing data on age at and length of evacuation, respectively, and one man had missing data on father’s occupational status in childhood. In this study, the analyses are based on 83 evacuated men and 83 non-evacuated controls matched for sex, birth year and father’s occupational status in childhood. For this group the mean age was 64.0 years (s.d.=2.9) for separated and 62.9 (s.d.=2.5) for non-separated individuals. The mean difference in birth year is 1.21 years (P-value=0.01) such that evacuated individuals were born on average earlier. This reflects the fact that ‘matching’ in terms of birth year was not ‘perfect’ as older children were evacuated more frequently than younger children.

In 2009–2010 at an average age of 70.2 years (s.d.=2.8 and range=65.0–76.0 years), the evacuated cases and non-evacuated controls who were still traceable (n=65, 78.3% and n=63, 75.9%, respectively) were invited for a psychological follow-up, including a re-test on depressive symptoms. Of the evacuated cases and controls, 20 and 20 had died, their addresses were not traceable or they had refused participation in further follow-ups, respectively. Of them, 45 and 52 had data available on depressive symptoms.

The clinical variables available for the cohort included age at separation, length of separation, socioeconomic status and education level, history of mental health disorders and a number of biological measures including glucose, insulin, IL6, TNFα and CRP. The Beck Depression Inventory16 (BDI; performed at the 2001–2004 clinical assessment) and the BDI II17 (performed at the 2009–2010 clinical assessment) were used to measure the frequency of depressive symptoms. The BDI and BDI II consist of 21 items assessing symptoms of depression during the past two weeks. Each item contains four statements reflecting varying degrees of symptom severity. Respondents are instructed to circle the number that corresponds with the statement that best describes them. Ratings are summed to calculate a total score which can range from 0 to 63. Although the BDI and the BDI II are designed to screen but not diagnose major depression, BDI and BDI II cutoff scores of 10 and 14 or more, respectively, are suggestive of mild-to-severe depressive symptoms.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from EDTA-anti-coagulated whole peripheral blood collected at the first clinical assessment (2001–2004) using the QIAamp DNA Blood Maxi Kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK). The samples were stored at −20 °C before and after DNA extraction.

DNA methylation analysis

DNA methylation analysis was performed at the Genetics Core of the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility (Edinburgh, UK). Bisulphite conversion of 500 ng input DNA was carried out using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research, Freiburg, Germany). Four microlitres of bisulphite-converted DNA was processed using the Infinium HD Assay for Methylation. This was performed using the Illumina Methylation 450 k beadchip and Infinium chemistry (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Each sample was interrogated on the arrays against 485 000 methylation sites. The arrays were imaged on the Illumina HiScan platform and genotypes were called automatically using GenomeStudio Analysis software version 2011.1.

Data analysis

Data processing

Data were processed with the Lumi23 package of Bioconductor,24 with Infinium-centric routines. CpG loci were annotated with the gene of the nearest transcription start site, as defined in UCSC hg19 and retrieved with the ‘Genomic Features’25 Bioconductor package. Variables associated with each individual were examined independently for association with M values of methylation using the ‘phenotest’ Bioconductor package. P-values were corrected for probe-wise multiple testing with the Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) method. To remove any variable associations indicated by chance, a variable was only considered further if at least one probe passed a variable-wise Bonferroni correction. Having removed such spurious associations, downstream analyses were applied to values without this second correction. Individual pairwise contrasts were then constructed from the pairs of values for all categorical variables and examined for differential methylation using (a) linear modelling using Limma,26 including adjustment for multiple testing and (b) the methyAnalysis package to smooth processed data and identify differentially methylated regions by use of t-tests applied between groups (also BH-corrected for multiple testing).

Gene set enrichment

Gene set enrichment was analysed using annotations from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)27 and Gene Ontology.28 Only probes with methylation above a background of 0.2 in at least 17 (~10%) of samples were used in the enrichment background set. Enrichment was assessed by the use of hypergeometric statistic as implemented in the GO stats package of Bioconductor.

Genome location

To examine the genomic location of significantly associated loci independent of gene annotations, the genome was binned into overlapping bins of 100 kb in size and bins with three or more significant loci were reported.

Validation by pyrosequencing

Pyrosequencing was used to validate DNA methylation at five CpG sites within 200 bp of the TSS of the leucine-rich, glioma inactivated 1 (LGI1) gene and additionally at a number of CpG sites with a spectrum of high, low and intermediate methylation levels on the array (IL17C, SAGE1, MIR4493, MIR548M, CLDN9 and TACC3). Bisulphite conversion was performed on 1 μg of genomic DNA with the EZ DNA methylation kit (Zymo Research). The converted DNA was amplified using the AmpliTaq Gold 360 kit (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) with primers mapping to target regions containing CpGs assayed within the array. PCR primers (Supplementary Table 1) were designed using PyroMark Assay Design Software 2.0 (Qiagen). Pyrosequencing was performed using PyroMark Q24Gold reagents on a PyroMark Q24 Pyrosequencer (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were extracted and analysed using PyroMark Q24 1.0.10 software (Qiagen). Background non-conversion levels were <3%.

Results

Association of methylation with clinical variables

Principal components analysis showed no clear clusters and no obvious differences between the way separated and non-separated individuals or different socioeconomic groupings clustered. Linear modelling between clinical variables and methylation showed no associations between DNA methylation and most clinical variables including separation status and socioeconomic status. There were significant associations between DNA methylation in peripheral blood taken at the first clinical assessment (2001–2004) and categorical scores on the BDI II performed at the second assessment some years later (Table 1). When specific contrasts in categorical variables were queried using linear modelling, differential methylation was identified at 474 probes representing 445 genes, all of which associated with the clinical cutoffs indicative of at least mild depressive symptoms on the BDI II (representing a score of 14–25; Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2). This contrast involves a relatively small number of eight individuals, compared to 88 individuals with minimal depressive symptomatology (a score of 1–13). Running methyAnalysis with its associated smoothing produced a larger number of significant probes (491 probes representing 351 genes; Table 1), again predominantly in association with BDI II categorical score indicative of at least mild depressive symptoms. Of these, 80 genes showed differential methylation at more than one probe. There were 170 of the significant probes and 175 associated genes present in the lists from both methods. MethyAnalysis results were used in subsequent analyses.

Table 1 - Significant associations between methylation and BDI II score.For genes, which had methylation changes observed in the same direction for more than one CpG site, DNA methylation was decreased in ~2/3 and increased in ~1/3 in association with a BDI II score indicative of at least mild symptomatology (Table 1). Differential methylation in association with a BDI II score indicative of mild depressive symptoms was identified at a number of genes with possible roles in brain development and/or function (Table 2), all of which showed hypomethylation (Figure 1). Among the most well-supported genes in terms of multiple significant probes were LGI1 and LGI2 which are thought to have important roles in brain development and function.29,30 Hypomethylation was present at five probes within the promoter of LGI1,31 and at three probes in a CpG island shore close to LGI2. Overall, significant loci were more likely to be identified in CpG island shores rather than in CpG islands or at the TSS (χ2 P-value=6 × 10−8; Supplementary Table 3), in agreement with the data from a study in postmortem brains.32 A number of 100 Kb bins in the genome contained three or more significant loci in the output from methyAnalysis associated with Beck Depression Questionnaire (Table 3).

Full table

Figure 1. - Differential methylation in association with Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI II) score. Hypomethylation was present at multiple probes corresponding to genes with possible roles in brain development and/or function. BDI II=1 indicates a score of 1–13, that is, minimal symptomatology; BDI II=2 indicates a score of 14–25, that is, at least mild symptomatology. Full figure and legend (106K)Table 2 - Genes with differential methylation in relation to depression scores which may be involved in the development and functioning of the brain.

Full tableTable 3 - 100 Kb bins in the genome containing three or more significant loci in the output from methyAnalysis associated with Beck Depression Questionnaire.

Full table

Pathway analysis

Analysis of gene ontology for the genes associated with altered DNA methylation and BDI II score using the molecular function, cellular component and biological processes categories of the Gene Ontology database28 revealed enrichment of a number of gene ontology terms, particularly within the molecular function and biological processes categories (Table 4). Mean methylation was decreased for all the genes within enriched pathways. The set of overrepresented categories included a significant number associated with development and morphogenesis, and DNA and transcription factor binding. In addition, consistent with the findings of a recent study in postmortem brain from individuals with depression compared with individuals without, a number of the identified gene sets are involved in programmed cell death;32 notably, hypomethylation was also found in association with depression in this study.

Table 4 - Gene enrichment: gene ontology overrepresented categories following assessment of DNA methylation differences in association with mild depression on the BDI II scale.

Full table

Array validation

To validate the array findings, pyrosequencing was performed to confirm the findings at LGI1 and additionally for a number of genes which had low, high or intermediate methylation levels. DNA methylation levels at the five CpG sites within the promoter of LGI1 were highly correlated with each other (r=0.68–0.98; P<0.01) and highly significant correlations between array and pyrosequencing data were confirmed for all five CpGs (r=0.86–0.97; all P<0.0001). Significant correlations were also confirmed for probes located in IL17C, SAGE1, MIR4493 and MIR548M (r ranging from 0.28–0.97, all P<0.05. Combining all loci: r=0.9770; P<0.0001). Although no correlations were observed between the array and pyrosequencing for CLDN9 and TACC3, this is not surprising as pyrosequencing analysis revealed that DNA methylation levels were <5% at these loci, which is below the reliable limit of detection.

Discussion

Studies in animal models have shown a significant influence of early-life adversity on behaviour and stress axis responsiveness (reviewed in ref. 44). ELS in rodents is associated with effects on DNA methylation in the brain in both candidate gene45, 46, 47 and genome-wide studies.48 In humans, genome-wide methylation profiling of hippocampal tissue from suicide victims has revealed that experience of abuse during childhood is associated with altered DNA methylation at multiple gene promoters.49 Importantly, and perhaps not surprisingly given that the long-term effects of ELS are seen in multiple systems, changes in DNA methylation have also been reported in cells which are more accessible for large studies in human populations, for example, lymphocytes and buccal cells. Altered DNA methylation has been found in DNA from buccal cells from adolescents whose parents reported experiencing high levels of stress during their children’s early years50 and a recent small study in children showed differences in DNA methylation in peripheral blood between children raised by their parents and children who had been institutionalized.51 Furthermore, candidate gene studies in peripheral blood DNA have identified associations between ELS and DNA methylation at the glucocorticoid receptor52, 53, 54, 55 and the serotonin transporter.56, 57, 58 Nevertheless, not all studies report differences in DNA methylation as a consequence of ELS, for example, Smith et al.59 found no association between child abuse and global or gene-specific DNA methylation in peripheral blood from African-American adults.

Although the deleterious effects of separation in infancy and childhood persist throughout life, so that more than 60 years later, those who were evacuated in infancy/childhood, when compared with non-evacuated individuals, display over 20% higher levels of depressive symptoms,5 a more than twofold higher risk of cardiovascular morbidity and a 1.4-fold in type 2 diabetes risk,11 we did not identify differences in DNA methylation between men who were separated from their families compared with men who remained with their families. In addition, although several studies have reported associations between early-life socioeconomic status and DNA methylation in adulthood,60,61 we found no evidence for this in these men from the HBCS. This is one of the largest studies of genome-wide methylation in the context of ELS and the individuals participating in the study have been extremely well phenotyped. The men studied here were not selected on the basis of current mental health status and although other studies have reported small differences in DNA methylation at candidate genes in otherwise healthy adults with a reported history of ELS,56,57 others have reported effects of ELS on DNA methylation specifically in the context of ongoing mental health disorders,52,62 so that this may be one explanation for the lack of any association between ELS and DNA methylation in the HBCS.

We did identify differences in DNA methylation at a number of genes in association with the development of at least mild depressive symptomatology over the subsequent 5–10 years. Differential methylation in association with a BDI II score indicative of mild depressive symptoms was identified at a number of genes with possible roles in brain development and function, all of which showed hypomethylation, consistent with recent studies in brain tissue from individuals with depression, although the mechanisms accounting for this loss of methylation is not clear.32 Notably, differential methylation was noted at a number of CpGs within the promoter of LGI1, a gene associated with epilepsy and psychiatric disorders.30 LGI1 appears to function in the synapse and has important roles in brain development and function, including in the regulation of postsynaptic function during development, in dendritic pruning and in the maturation of pre- and postsynaptic membrane functions of glutamatergic synapses during postnatal development.29,30 Differential methylation was also noted near the gene encoding LGI2; intriguingly, differential methylation at LGI2 has previously been identified in association with major depressive disorder (MDD).36

Consistent with studies showing alterations in DNA methylation in postmortem brain or blood of individuals with MDD, major psychosis and posttraumatic stress disorder, the observed differences in DNA methylation in our study were small (generally <10%).36,62, 63, 64 Three recent studies have analysed DNA methylation in individuals with MDD compared with a control population.32,36,65 Using DNA from peripheral blood Byrne et al.65 found no significant methylation differences between twins discordant for MDD although the twins with MDD showed increased variation in methylation across the genome. Another slightly larger study identified DNA methylation differences at 224 candidate regions, which were highly enriched for neuronal growth and development genes in DNA from frontal cortex collected from postmortem brains.36 While the differentially methylated gene regions identified in brain in the latter study showed little overlap with those identified in the HBCS, analysis of gene ontology identified an overrepresentation of developmental pathways in both studies, suggesting potential common mechanisms in the pathogenesis of depression.

There are tissue-specific differences in DNA methylation profiles, which are likely to reflect cellular identity and tissue function,66,67 so that it is difficult to infer causality from studies performed on DNA from peripheral blood with respect to conditions primarily affecting other organs. For studies in the brain, this is further complicated by differences in DNA methylation across different brain regions, which may be one explanation for the disparities between studies.68 Detailed studies of different regions of the brain in specific disease states are needed to identify additional and/or more subtle epigenetic changes which may be particularly pertinent to particular phenotypes and which can be related to gene expression and function in the region of interest.49,63 Nevertheless, as data from an increasing number of studies suggest that some disease-relevant epigenetic changes are conserved across different tissues,64,69, 70, 71, 72 the findings from studies using accessible tissues such as blood may indeed give important insights into disease pathogenesis and lead to the development of new biomarkers which can be utilized in population studies.

In conclusion, although we were unable to identify differences in DNA methylation as a consequence of early-life separation in a large study of well-phenotyped men from the HBCS, methylation differences were identified in peripheral blood in association with the finding of depressive symptoms some 5–10 years later. Although the numbers of men with at least mild depressive symptoms was small compared with those without, the numbers are comparable to other studies of this nature in individuals with psychiatric disorders.32,64,65 Our study involved only a cohort of well-studied men, closely matched for a number of factors including age, for whom longitudinal data were available and such prospective cohort studies have been highlighted as being of particular importance in improving the understanding of the role of age-related epigenetic changes in the development of disease;73 further studies will be necessary to study any similar effects in women. The findings of hypomethylation in association with the subsequent development of depressive symptoms, and the identification of common pathways and candidate genes are in agreement with other studies. Our results support the concept that DNA methylation differences may be important in the pathogenesis of psychiatric disease and raise the intriguing possibility that changes in DNA methylation may be predictive of the development of depression.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References at the Nature Translational Psychiatry site.