In 2001, the LA Times wrote about the emergence of a new salon culture in Los Angeles, frequented by writers, filmmakers, and actors. This phenomenon is the re-emergence of a salon culture, which began originally in the 16the century in Italy, but is most often associated with the 17th and 18th century literary culture of France.

In 2011, both Alternet (US) and The Telegraph (UK) did articles on salon culture. This is a bit of the history of American salons from the Alternet article:

The modern salon formally emerged in New York during the early 20th century. Edith Wharton, who loathed the American literary scene and resettled in Paris in 1907, likely attended the intellectual gatherings hosted by her sister-in-law, Mary Cadwalader Jones, on East 11th Street. In 1900, Jones gained national prominence championing the role of nurses in public health, fiercely arguing for the professionalization of a traditionally female vocation. She enjoyed intellectual life and hosted "Mary Cadwal's parlor” at which many leading intellectual lights of the day were regulars, including the writers Henry James, Henry Adams and F. Marion Crawford, the painters John LaFarge and John Singer Sargent, and the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens.I wish there were something like this in Tucson today. It would be awesome to meet up with a group of intelligent and educated people to exchange ideas, explore new topics, and generally hear new ideas or new perspectives.

However, it was Mabel Dodge’s famous “Evenings,” hosted at her townhouse at 23 Fifth Avenue during the 1910s, that made salons part of the city’s social life. Dodge was a classic Gilded Age “poor little rich girl,” a spoiled dilettante and libertine who, until she found her calling, attached herself to the latest fad and male celebrity. In 1913 she helped organize the controversial International Show of Modern Art, popularly known as the Armory Show, which launched modern art in America. That same year, she joined John Reed, “Big Bill” Hayward and Emma Goldman in support of the IWW-backed silk workers strike in Paterson, NJ, playing a leading role organizing the controversial, “Pageant of the Paterson Strike,” held at Madison Square Garden.

Dodge’s salons were organized along the lines of the traditional discussion-group format known as the General Conversation. An appointed leader, normally a specialist in an artistic, academic or political subject, offered a brief introductory commentary focusing the discussion and then invited those in attendance to jump into the discussion. Salon leaders ranged from A. A. Brill on Sigmund Freud and psychoanalysis, Reed on Pancho Villa and the Mexican Revolution, Margaret Sanger on birth control and women’s rights and even African-American entertainers from Harlem.

As the scholar Andrea Barnet reminds us, “Dodge’s salon was where black Harlem first met Greenwich Village bohemia and, conversely, where white bohemia got its first taste of a parallel black culture that it would soon not only glorify but actively try to emulate.”

I said this out loud the other night, so my girlfriend immediately mentioned to a friend on Facebook, and he and his wife like the idea, so maybe it will happen. And as tradition holds, the salon is often hosted by a female, the Salonnière.

The article below is about one of the major ongoing salons in the 20th-21st century - the Edge Salons hosted by John Brockman.

Salon Culture: Network of Ideas

A Conversation with Andrian Kreye [10.2.14]

Despite their intense scientific depth, John Brockman runs these gatherings with the cool of an old school bohemian. A lot of these meetings indeed mark the beginning of a new phase in science history. One such example was a few years back, when he brought together the luminaries on behavioral economics, just before the financial crisis plunged mainstream economics into a massive identity crisis. Or the meeting of researchers on the new science of morality, when it was noted that the widening political divides were signs of the disintegration of American society. Organizing these gatherings over summer weekends at his country farm he assumes a role that actually dates from the 17th and 18th century, when the ladies of the big salons held morning and evening meetings in their living rooms under the guise of sociability, while they were actually fostering the convergence of the key ideas of the Enlightenment.

Salon Culture

NETWORK OF IDEAS

The Salon was the engine of enlightenment. Now it's coming back. In the digital era the question might be different from the ones in the European cities of the 17th century. The rules are the same. Why is there such a great desire to spend some hours with likeminded peers in this age of the internet?

by Andrian Kreye, Editor, The Feuilleton (Arts & Essays), Süddeutsche Zeitung, Munich.

The salon, which marked a entire era: Duchess Anna Amalia of Saxe-Weimar with her guests, including Goethe (third from left) and Herder (far right).

For more than a century now the salon as a gathering to exchange ideas has been a footnote of the history of ideas. With the advent of truly mass media this exchange had first been democratized, then in rapid and parallel changes diluted, radicalized, toned down, turned up, upside and down again. It has only been recently that a longing emerged for those afternoons in the grand suites of the socialites in the Paris, Vienna, Berlin or Weimar of centuries past, where streams of thought turned into tides of history, where refined social gatherings of the cultured elites became the engine of the Enlightenment.

Just like back then, today's new salons are mostly exclusive if not closed circles. If you do happen to be invited though you will swiftly notice the intellectual force of those gatherings. On a summer's day on Eastover Farm in Connecticut for example, in the middle of green rolling hills with horse paddocks and orchards under the sunny skies of New England. This is where New York literary agent John Brockman spends his weekends. Once a year, he invites a small group of scientists, artists and intellectuals who form the backbone of what is called the Third Culture. Which is less of a new culture, but a new form of debate across all disciplines traditionally divided into the humanities and the natural sciences, i.e., the first and second culture.

On that weekend, for example, he had invited a half-dozen men. Each of whom had a large footprint in their respective disciplines: the gene researcher Craig Venter, who was the first to sequence the human genome; his colleague George Church, Robert Shapiro, who explored the chemistry of DNA, the astronomer Dimitar Sasselov, quantum physicist Seth Lloyd, and the physicist Freeman Dyson, who sees in his his role as scientist the need to continually question universally accepted truths. A few science writers were also present, along with Deborah Triesman, literary editor at the New Yorker.

At some of his other meetings, the number of Nobel Laureates might have been higher, but the question under discussion in the warm summer wind among rustling tops of maple trees with jugs full of freshly made lemonade, carried utmost weight: "What is life?" Seth Lloyd formulated the problem right at the start: science knows everything about the origin of the universe, but almost nothing about the origin of life. Without this knowledge, the sciences, on the threshold of the biological age, are groping in the dark.

Brockman had deliberately chosen the invited scientists as representatives of different fields, who, for years, had understood the need to think across the scientific disciplines. But even then, you could feel like an outsider, as was the case when Robert Shapiro made a joke about ribonucleic acids, which was greeted with boisterous laughter by the scientists.

Despite their intense scientific depth, John Brockman runs these gatherings with the cool of an old school bohemian. A lot of these meetings indeed mark the beginning of a new phase in science history. One such example was a few years back, when he brought together the luminaries on behavioral economics, just before the financial crisis plunged mainstream economics into a massive identity crisis. Or the meeting of researchers on the new science of morality, when it was noted that the widening political divides were signs of the disintegration of American society. Organizing these gatherings over summer weekends at his country farm he assumes a role that actually dates from the 17th and 18th century, when the ladies of the big salons held morning and evening meetings in their living rooms under the guise of sociability, while they were actually fostering the convergence of the key ideas of the Enlightenment.

Not all salonnières were content to play the host role—Johanna Schopenhauer (the mother of the philosopher Arthur, here with her daughter Adele) was a significant writer with an extensive oeuvre.The salon is still regarded as a mysterious world of thoughts and ideas, a world in which the participants soon were consigned to the role of historical figures in history books. In the early days of the salon culture these meetings were incubators of new ideas as well as the first form an urban and bourgeois culture. The first salons were formed in Paris in the early 17th century, when the nobles left their estates and are gathered in the capital around the King. Initially, they cemented these early manifestations of bourgeois culture such as music and literature. But soon philosophers such as Voltaire and Diderot appeared in the 18th century and prepared the intellectual ground for the French revolution.

In all major cities in Europe, it soon was common for ladies of high society to gather influential thinkers around them. Often, these were for their time radical gatherings, because those salons dissolved the rigid boundaries between social classes. With rational thinking of the Enlightenment, the reputation enjoyed by a person was measured in terms of intellect, not status or wealth. Berlin and Vienna were established, next to Paris, as cities of culture of the salon. But in small towns too, the intellectual life soon revolved around salons. The salons in Weimar were legendary, where Johanna Schopenhauer, the mother of the future philosopher, Arthur, and the Duchess Anna Amalia of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, counted Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller among their guests.

At the end of the 18th century, the revolutionary spirit was present in the salons of Caroline Schelling in Mainz. The Prussian military arrested Schelling in 1793 for her links to the Jacobins.At the same time England developed the first coffee house culture. In 1650, the first English cafe, called Grand Café, opened in Oxford. The open structure of the cafés had a tremendous effect on the culture of debate, but so did coffee and tea, the new drinks from the colonies. In a country in which the entire population at any time of day was drinking alcohol, the stimulant of caffeine acted as fertilizer for the burgeoning idea cultures. But it was mostly the lounges and cafes in Europe (and later America) that gave birth to the fundamental principle of progress and innovation, namely the network. Indeed, it was rarely the sudden Eureka-moments in the solitude of the laboratory of the study, that scientists and thinkers brought humanity from the dark times of the pre-modern era into the light of reason. It was the fierce debates held in the lounges and cafes that allowed the ideas behind these Eureka-moments to mature.

The salon of the Duchess Anna Amalia was called "Garden of the Muses." In addition to her role as salonnière, the Duchess was also generous patron of Goethe and Schiller.

No wonder that the nostalgia for these meetings between big thinkers is so strong today. With his 2010 film "Midnight in Paris", Woody Allen, the greatest of the urban romantics, created a cinematic monument to this nostalgia. As the American author Gil Pender roams the nighttime streets and alleys of Paris, he accidentally falls into a time portal and lands in the Paris of the 1920s. There, in the rooms of the writer and collector Gertrude Stein with walls covered in works of art, he meets Pablo Picasso, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel. This is a tribute to the small world of bohemians who gave birth to so many great things in the history of culture.

This nostalgia fits perfectly in an age when the mass media abandon models of publications and programs to turn into networks with an infinite number of nodes. Facebook, Twitter and countless blogs and forums perfectly simulate this exciting exchange of ideas for an audience of billions. In terms of today's digital Weltgeist, there is already talk about the global salon, and a universal brain. Could it be that nostalgic interest in the salons of the past is a desire for more clarity to face the complexity of the networked future?

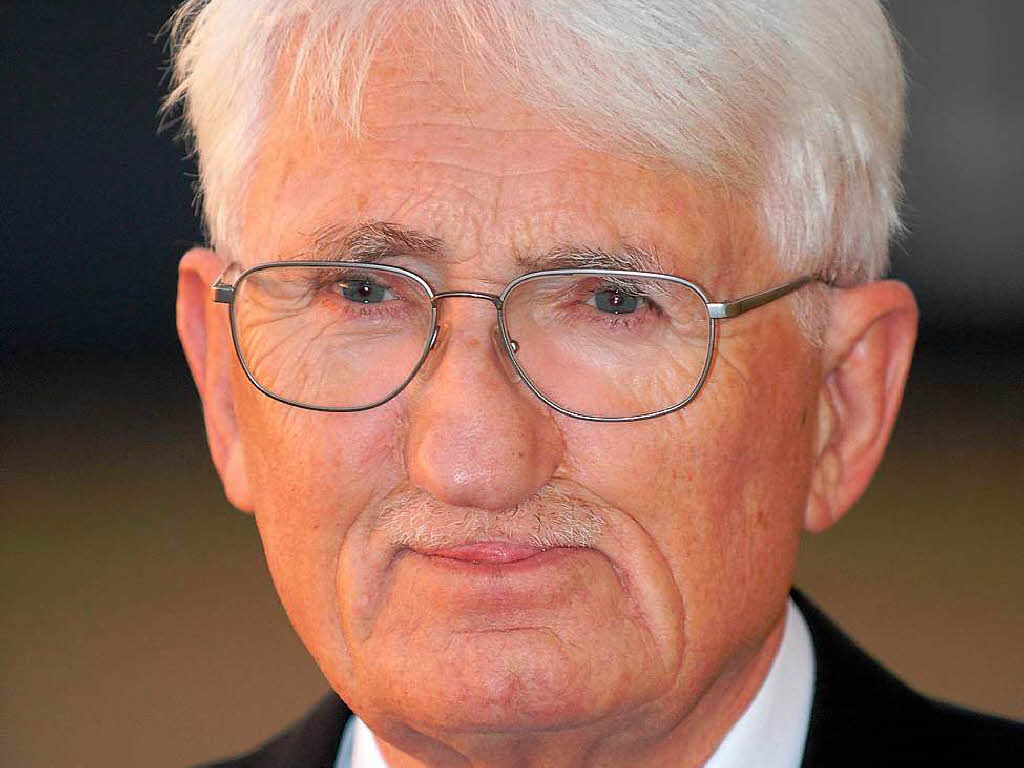

In the digital era we might very well witness once again the phenomenon that Jürgen Habermas has called "structural transformation of the public sphere", the rise of a new bourgeoisie and mass society that began with the salons. There is no across-the-board answer to this question, that's impossible when the structural transformation of the digital age affects various spheres of the international community differently. In Europe and America, digital media always leads to new cul-de-sacs and roundabouts of communication. Social networks claim to be not only the successors of salons, they evoke the ominous metaphysical principle of the Weltgeist (global mind), while they actually reduce the principle of intellectual eruptions in salons to a de-intellectualized white noise.

Salon of the 21st century: the literary agent John Brockman (Center, with Hat) in the circle of the scientists of the Edge network during one of his legendary weekends at Eastover Farm in Connecticut.In emerging and developing countries on the other hand, the use of digital media has indeed made Habermas's structural transformation of the public possible, in much the same way as in the Europe of the Enlightenment in terms of the salons and the early mass media. In countries like Iran, Egypt or the Ukraine, each change begins with dangerous ideas, because if ideas are to make a difference, they must be dangerous.

Salon of the 21st century: the literary agent John Brockman (Center, with Hat) in the circle of the scientists of the Edge network during one of his legendary weekends at Eastover Farm in Connecticut.In emerging and developing countries on the other hand, the use of digital media has indeed made Habermas's structural transformation of the public possible, in much the same way as in the Europe of the Enlightenment in terms of the salons and the early mass media. In countries like Iran, Egypt or the Ukraine, each change begins with dangerous ideas, because if ideas are to make a difference, they must be dangerous.

This was no different in the early salons. If the great intellectuals and artists of the time met in the literary salons, it was by no means solely to discuss questions of aesthetics or literary forms. In the late 18th century salons of the woman of letters Caroline Schelling, for example, in Mainz and Göttingen, were collecting revolutionary spirits who took a stand in Paris, at the dawn of a new era that brought the demise of the monarchy. Caroline Schelling was arrested, slandered, vilified, but it did not change the fact that, under her leadership, the Jacobins eventually formed in Germany as well as a force opposing the monarchy and empire.

This is the very reason that an autocracy such as China uses its power to promote the social concept of the individual, because a single individual cannot spread dangerous ideas. This fear of the power of networks also explains the unusually harsh persecution of religious communities. It's bad enough that faith calls into question the sovereignty of the party on thinking. However there is a danger for power is also lurking in the networks of churches and monasteries. Faith calls into questions the sovereignty of the party line of thinking and thoughts. Danger lurks for those in power in the networks of churches and monasteries.

In the birthplaces of the enlightenment, in America and Europe, the current struggle for sovereignty over interpretation is not a political fight though—this has dissolved since the end of ideologies in countless, often regional micro-conflicts. Similarly, the battle between religion and science has been in play for a long time. Yet it is science that challenges the certainties.

The Internet has the possibility to enlarge the circle of great minds that exchange ideas ad infinitum. To not get lost in the vastness of cyberspace, thinkers and creators have started to meet again on a regular basis for various new forms of salons like DLD; the Aspen Ideas Forum or the TED Conference. What started as an elite gathering of Silicon Valley pioneers thirty years ago has turned into a global forum of ideas, which are spread via internet videos of lectures and talks. Twice a year about a thousand scientists, artists, activist and entrepreneur come together in one place like Monterey, Vancouver, Oxford or Rio, to learn about new ideas "worth spreading" to quote the motto of the conference. In a lot of cases, such ideas will have an impact on the world for years on end.At this point, the memory of that summer day in Connecticut comes into focus, and the moment when the scientists asking questions about the origin of life talked about their research and projects. Craig Venter told of his plans to develop bacteria that could supplant fossil fuels as an energy source. George Church described the sequencing of the genome of the Mammoth. Dimitar Sasselov reported by his search for Earth-like planets. Seth Lloyd explained the unprecedented opportunities of the quantum computer. What, for the onlookers under the maple trees only a few years ago sounded like science fiction, is today, to a large extent, scientific reality.

In the New York of the 1960s, hardly anyone understood the network of eccentric artist Andy Warhol, as seen here with John Brockman (left) and Bob Dylan (right) in the "Factory", a hybrid of salon, studio, and party room.Of course, John Brockman long ago put his salon online. Leading scientists, artists, prominent intellectuals, regularly meet on his edge.org website to have a conversation about the issues of our time. Annually, there is a concerted action in which he asks the entire network a big question. Eight years ago, the following was central issue for this salon culture: "What is your most dangerous idea?" More than a hundred responses were submitted and published. It reads like intellectual fireworks. In your own head, you quickly feel for yourself how ideas clash, release energy and generate new ideas. It is then that you experience the intellectual thrill that has always inspired the salons.

In the meantime, Brockman's arena of ideas has sparked countless likeminded gatherings of all scales and fields. Conferences have been established as a distinct independent form of communication, because the network tends to be significantly more effective and fruitful beyond the Internet. Other than the observable external format, events such as the TED Conferences, the Aspen Ideas Festival, PopTech, or the Digital Life Design (DLD), have little in common with the congresses and meetings of old. They have long since become the new crucibles in the history of ideas. Especially the American TED Conference has shown in recent years the way in the salon of the 21st century can evolve. What started in 1984 as a meeting of Silicon Valley elites under the banner "Technology, Entertainment, Design", is now a global network that utilizes all channels of communication—conferences, online videos, books, TV, radio, blogs to make ideas blossom and develop on a global scale. Twice a year, a small circle from this large network meets in a cosmopolitan city ... in the spirit of the salons of yesteryear.